“Street Life of Peking,” 1921. The New York Public Library, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs.

Each year, the Cundill History Prize celebrates the best history writing in English. Lapham’s Quarterly invited the finalists for the 2023 Cundill History Prize to share their favorite works of history—the books that sparked their lifelong interest in the past and to which they return for inspiration and enjoyment.

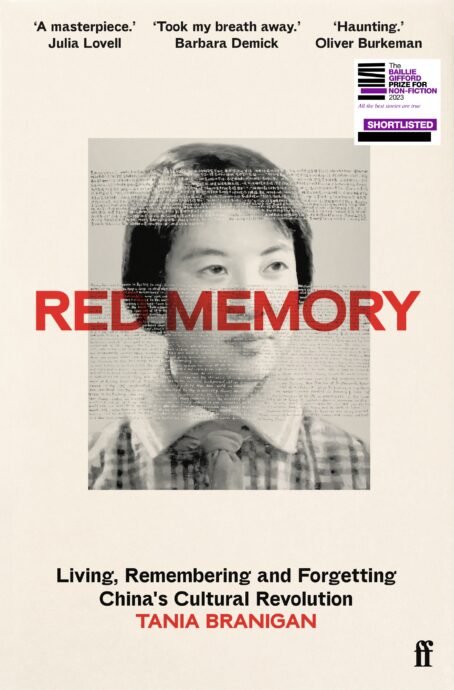

Today’s reading list comes from Tania Branigan, author of Red Memory: Living, Remembering, and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution, out now from Faber (UK) and W.W. Norton (U.S.).

The Cultural Revolution, unleashed by Mao Zedong in 1966, was a decade of violence and chaos in which tens of millions of people were hounded and two million died. Red Memory explores what it means to China today. I traveled across the country to talk to those who lived through it, interview scholars, and visit graves, museums, and even theme restaurants. While the era is not utterly taboo in China, discussion of it is carefully policed. The Communist Party’s version of history is grand, heroic, top-down, and above all, instrumental. It’s not a record, still less a debate, but a tool for producing political outcomes. I am interested in history as it is lived and shaped by ordinary people, which is messier and more nuanced.

The Cultural Revolution clearly shows how one powerful man can alter the course of countless millions of lives. Many historians have studied how Mao set it in motion. But vast numbers of people actively, and often enthusiastically, participated: Without them, the movement could not have consumed the country as it did. I am interested in their relationship to the past and what the revolution means to them now. Everyone in Red Memory had remembered while others forgot; I wanted to know not just what happened to them, but how they understand and make sense of their pasts. What stories do they tell about the things they have done and the things that have been done to them?

The three books I’ve chosen illuminate these themes. The Cultural Revolution won’t be repeated, but human nature doesn’t change, as Philip Kuhn’s book makes clear. Svetlana Alexievich powerfully connects personal experience with vast political shifts. And Howard French shows how unreliable accepted historical narratives can be.

Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768, by Philip A. Kuhn

This book is an extraordinary tale of an outbreak of mass hysteria over alleged sorcery, and a brilliant exploration of eighteenth-century China, full of unexpected and fascinating detail. Kuhn reveals how power and politics work—townspeople accused outsiders; officials framed the innocent to satisfy superiors. There are obvious echoes of the Cultural Revolution, but also of witch hunts elsewhere.

Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, by Svetlana Alexievich

Oral histories can feel formulaic, but Alexievich’s investigation into the end of the Soviet Union is so rich and humane—there’s a whole world within its pages. Her interviewees range from Gulag survivors to an advertising manager. Empty mayonnaise jars, flowers, and kisses are recorded alongside Stakhanovite campaigns, labor camps, and coups. At one point, a former Kremlin official scolds Alexievich for putting too much stock in “human truth”; no one has better shown why personal truths matter, and why the grand sweep of history coexists with the mundane and intimate.

Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War, by Howard W. French

It still amazes me that I studied the Industrial Revolution repeatedly and at length as a schoolchild growing up in the north of England—and yet I do not recall anyone even mentioning the British Empire, which would have helped make sense of it all. This is an eye-opening book, containing so much I should have known. In his words: “Europe’s deep and often brutal ties with Africa drove the birth of a truly global capitalist economy…[Slave-grown] sugar completely revolutionized European society.”

About the Cundill History Prize

The Cundill History Prize recognizes and rewards the best history writing in English. A prize of $75,000 is awarded annually to the book that embodies historical scholarship, originality, literary quality, and broad appeal. The two runners-up each receive $10,000. Administered by McGill University in Montreal and awarded by a distinguished jury, the Cundill History Prize honors the abiding passion for history of its founder, F. Peter Cundill, by encouraging informed public debate through the wider dissemination of history writing to new audiences around the world. Any historical period or subject is eligible, and translations into English are warmly welcomed. Books are accepted regardless of the nationality or place of residence of their authors.

Read finalist Kate Cooper’s reading list and finalist James Morton Turner's reading list.