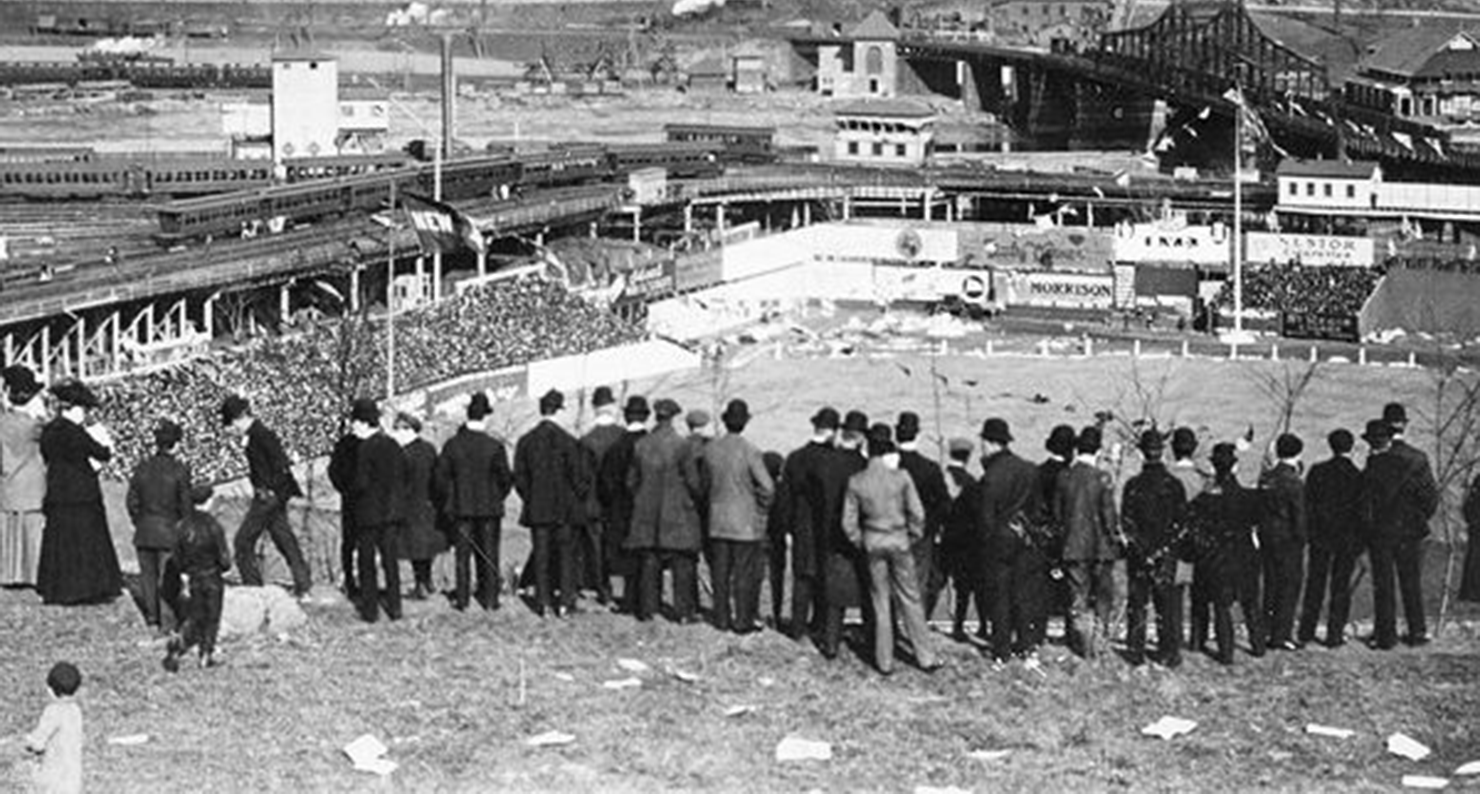

Baseball fans stand on Coogan’s Bluff to watch the New York Giants play the Chicago Cubs, Polo Grounds, New York City, September 23, 1908.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

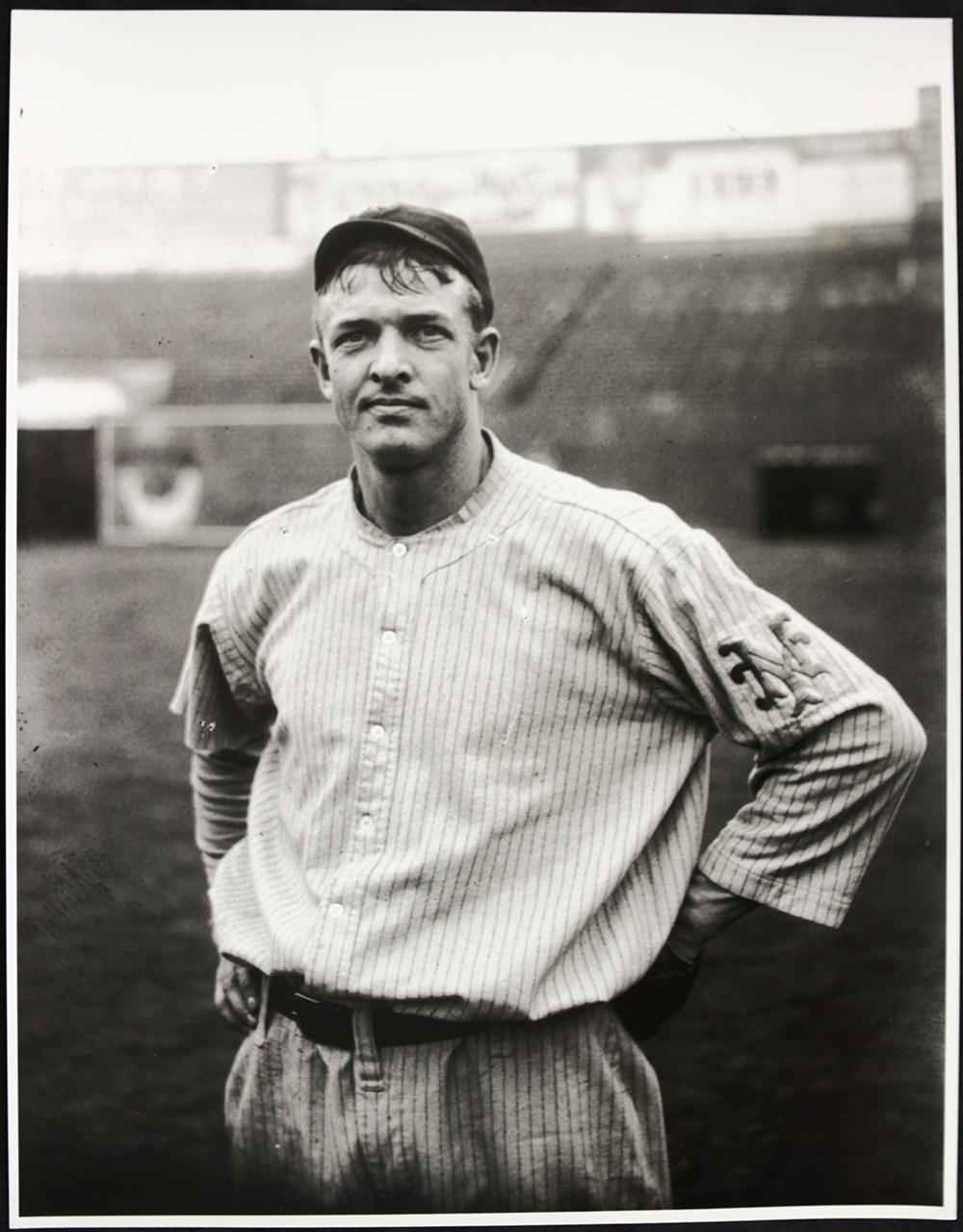

In 1908, the last year the Chicago Cubs won the World Series, the team’s path to the National League pennant led through the New York Giants. A dominant franchise at the time, the Giants held in their pitching rotation Christy Mathewson, one of the greatest pitchers ever to play baseball, who only three years earlier had pitched three complete-game shutouts in the 1905 World Series. In Mathewson’s memoir, Pitching in a Pinch, published in 1912 with the help of sportswriter John Wheeler, he recalls two pivotal 1908 games between the Giants and the Cubs—among the wildest and most memorable ever played—which set the Cubs on their journey to their second World Series title in as many years.

The New York Giants and the Chicago Cubs played a game at the Polo Grounds on October 8, 1908, which decided the championship of the National League in one afternoon, which was responsible for the deaths of two spectators, who fell from the elevated railroad structure overlooking the grounds, which made Fred Merkle famous for not touching second, which caused lifelong friends to become bitter enemies, and which, altogether, was the most dramatic and important contest in the history of baseball. It stands out from everyday events like the battle of Waterloo and the assassination of President Lincoln. It was a baseball tragedy from a New York point of view. The Cubs won by the score of 4 to 2.

Behind this game is some “inside” history that has never been written. Few persons, outside of the members of the New York club, know that it was only after a great deal of consultation the game was finally played, only after the urging of John T. Brush, the president of the club. The Giants were risking, in one afternoon, their chances of winning the pennant and the world’s series the concentration of their hopes of a season because the Cubs claimed the right on a technicality to play this one game for the championship. Many members of the New York club felt that it would be fighting for what they had already won, as did their supporters. This made bad feeling between the teams and between the spectators, until the whole dramatic situation leading up to the famous game culminated in the climax of that afternoon. The nerves of the players were rasped raw with the strain, and the town wore a fringe of nervous prostration. It all burst forth in the game.

Among other things, Frank Chance, the manager of the Cubs, had a cartilage in his neck broken when some rooter hit him with a handy pop bottle, several spectators hurt one another when they switched from conversational to fistic arguments, large portions of the fence at the Polo Grounds were broken down by patrons who insisted on gaining entrance, and most of the police of New York were present to keep order. They had their clubs unlimbered, too, acting more as if on strike duty than restraining the spectators at a pleasure park. Last of all, that night, after we had lost the game, the report filtered through New York that Fred Merkle, then a youngster and around whom the whole situation revolved, had committed suicide. Of course it was not true, for Merkle is one of the gamest ballplayers that ever lived.

My part in the game was small. I started to pitch and I didn’t finish. The Cubs beat me because I never had less on the ball in my life. What I can’t understand to this day is why it took them so long to hit me. Frequently it has been said that “Cy” Seymour started the Cubs on their victorious way and lost the game, because he misjudged a long hit jostled to center field by “Joe” Tinker at the beginning of the third inning, in which chapter they made four runs. The hit went for three bases.

Seymour, playing center field, had a bad background against which to judge fly balls that afternoon, facing the shadows of the towering stand, with the uncertain horizon formed by persons perched on the roof. A baseball writer has said that, when Tinker came to the bat in that fatal inning, I turned in the box and motioned Seymour back, and instead of obeying instructions he crept a few steps closer to the infield. I don’t recall giving any advice to “Cy,” as he knew the Chicago batters as well as I did and how to play for them.

Tinker, with his long bat, swung on a ball intended to be a low curve over the outside corner of the plate, but it failed to break well. He pushed out a high fly to center field, and I turned with the ball to see Seymour take a couple of steps toward the diamond, evidently thinking it would drop somewhere behind second base. He appeared to be uncertain in his judgment of the hit until he suddenly turned and started to run back. That must have been when the ball cleared the roof of the stand and was visible above the sky line. He ran wildly. Once he turned, and then ran on again, at last sticking up his hands and having the ball fall just beyond them. He chased it and picked it up, but Tinker had reached third base by that time. If he had let the ball roll into the crowd in center field, the Cub could have made only two bases on the hit, according to the ground rules. That was a mistake, but it made little difference in the end.

All the players, both the Cubs and the Giants, were under a terrific strain that day, and Seymour, in his anxiety to be sure to catch the ball, misjudged it. Did you ever stand out in the field at a ballpark with thirty thousand crazy, shouting fans looking at you and watch a ball climb and climb into the air and have to make up your mind exactly where it is going to land and then have to be there, when it arrived, to greet it, realizing all the time that if you are not there you are going to be everlastingly roasted? It is no cure for nervous diseases, that situation. Probably forty-nine times out of fifty Seymour would have caught the fly.

“I misjudged that ball,” said “Cy” to me in the clubhouse after the game. “I’ll take the blame for it.” He accepted all the abuse the newspapers handed him without a murmur and I don’t think myself that it was more than an incident in the game. I’ll try to show later in this story where the real “break” came.

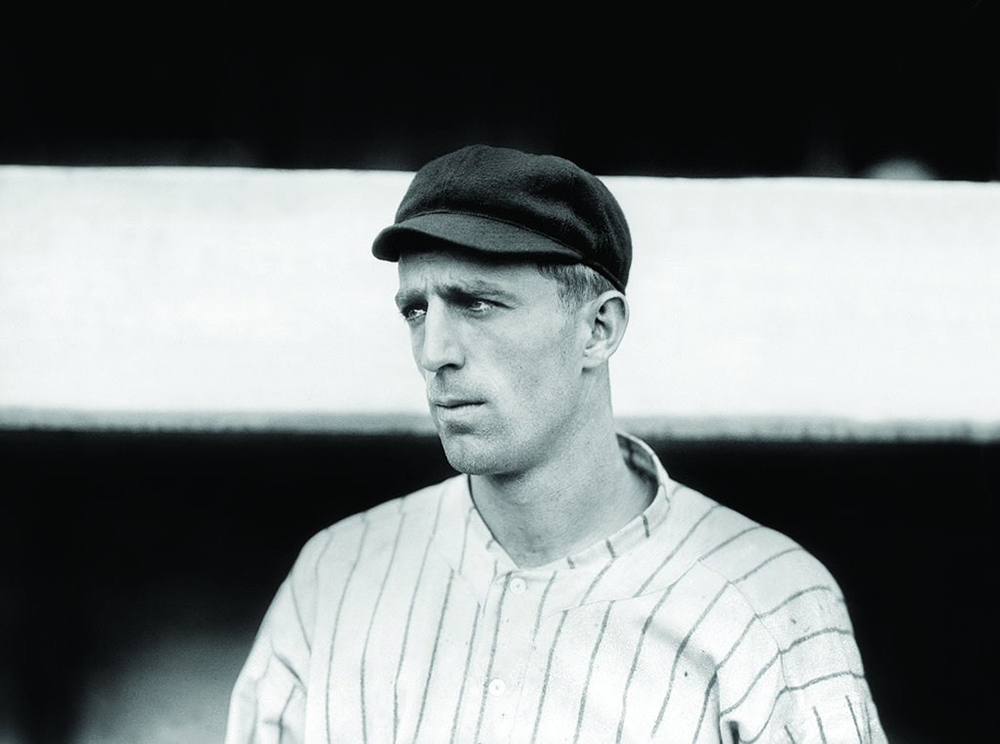

Just one mistake, made by “Fred” Merkle, resulted in this play-off game. Several newspaper men have called September 23, 1908, “Merkle Day,” because it was on that day he ran to the clubhouse from first base instead of by way of second, when “Al” Bridwell whacked out the hit that apparently won the game from the Cubs. Any other player on the team would have undoubtedly done the same thing under the circumstances, as the custom had been in vogue all around the circuit during the season. It was simply Fred Merkle’s misfortune to have been on first base at the critical moment. The situation which gave rise to the incident is well known to every follower of baseball. Merkle, as a pinch hitter, had singled with two out in the ninth inning and the score tied, sending McCormick from first base to third. “Al” Bridwell came up to the bat and smashed a single to center field. McCormick crossed the plate, and that, according to the customs of the League, ended the game, so Merkle dug for the clubhouse. Evers and Tinker ran through the crowd which had flocked on the field and got the ball, touching second and claiming that Merkle had been forced out there.

Most of the spectators did not understand the play, as Merkle was under the shower bath when the alleged putout was made, but they started after “Hank” O’Day, the umpire, to be on the safe side. He made a speedy departure under the grandstand and the crowd got the putout unassisted. Finally, while somewhere near Coogan’s Bluff, he called Merkle out and the score a tie. When the boys heard this in the clubhouse, they laughed, for it didn’t seem like a situation to be taken seriously. But it turned out to be one of those things that the farther it goes the more serious it becomes.

“Connie” Mack, the manager of the Athletics, says: “There is no luck in Big League baseball. In a schedule of one hundred and fifty-four games, the lucky and unlucky plays break about even, except in the matter of injuries.” But Mack’s theory does not include a schedule of one hundred and fifty-five games, with the result depending on the one hundred and fifty-fifth. Chicago had a lot of injured athletes early in the season of 1908, and the Giants had shot out ahead in the race in grand style. In the meantime the Cubs’ cripples began to recuperate, and that lamentable event on September 23 seemed to be the turning-point in the Giants’ fortunes.

Almost within a week afterwards, Bresnahan had an attack of sciatic rheumatism and “Mike” Donlin was limping about the outfield, leading a great case of “Charley horse.” Tenney was bandaged from his waist down and should have been wearing crutches instead of playing first base on a Big League club. Doyle was badly spiked and in the hospital. Our manager, John McGraw, had a new daily greeting for his athletes when he came to the park: “How are the cripples? Any more to add to the list of identified dead today?”

Merkle moped. He lost flesh, and time after time begged McGraw to send him to a minor league or to turn him loose altogether.

“It wasn’t your fault,” was the regular response of the manager who makes it a habit to stand by his men.

We played on with the cripples, many doubleheaders costing the pitchers extra effort, and McGraw not daring to take a chance on losing a game if there were any opportunity to win it. He could not rest any of his men. Merkle lost weight and seldom spoke to the other players as the Cubs crept up on us day after day and more men were hurt. He felt that he was responsible for this change in the luck of the club. None of the players felt this way toward him, and many tried to cheer him up, but he was inconsolable. The team went over to Philadelphia, and Coveleski, the pitcher we later drove out of the League, beat us three times, winning the last game by the scantiest of margins. The result of that series left us three to play with Boston to tie the Cubs if they won from Pittsburgh the next day, Sunday. If the Pirates had taken that Sunday game, it would have given them the pennant. We returned to New York on Saturday night very much downhearted.

“Lose me. I’m the jinx,” Merkle begged McGraw that night.

“You stick,” replied the manager.

While we had been losing, the Cubs had been coming fast. It seemed as if they could not drop a game. At last Cincinnati beat them one, which was the only thing that made the famous season tie possible. Next came the famous game in Chicago on Sunday between the Cubs and the Pittsburgh Pirates, when a victory for the latter club would have meant the pennant and the big game would never have been played. Ten thousand persons crowded into the Polo Grounds that Sunday afternoon and watched a little electric score board which showed the plays as made in Chicago. For the first time in my life I heard a New York crowd cheering the Cubs with great fervor, for on their victory hung our only chances of ultimate success. The same man who was shouting himself hoarse for the Cubs that afternoon was for taking a vote on the desirability of poisoning the whole Chicago team on the following Thursday. Even the New York players were rooting for the Cubs. The Chicago team at last won the game.

The National Commission gave the New York club the option of playing three games out of five for the championship or risking it all on one contest. As more than half of the club was tottering on the brink of the hospital, it was decided that all hope should be hung on one game. By this time, Merkle had lost twenty pounds, and his eyes were hollow and his cheeks sunken. The newspapers showed him no mercy, and the fans never failed to criticize and hiss him when he appeared on the field. He stuck to it and showed up in the ballpark every day, putting on his uniform and practicing. It was a game thing to do. A lot of men, under the same fire, would have quit cold. McGraw was with him all the way.

But it was not until after considerable discussion that it was decided to play that game. All the men felt disgruntled because they believed they would be playing for something they had already won. Even McGraw was so wrought up, he said in the clubhouse the night before the game: “I don’t care whether you fellows play this game or not. You can take a vote.”

A vote was taken, and the players were not unanimous, some protesting it ought to be put up to the League directors so that, if they wanted to rob the team of a pennant, they would have to take the blame. Others insisted it would look like quitting, and it was finally decided to appoint a committee. I was on it. We called an executive session, and we all thought of the crowd of fans looking forward to the game and of what the newspapers would say if we refused to play. It was rapidly and unanimously decided to take a chance.

That night was a wild one in New York. The air crackled with excitement and baseball. I went home, but couldn’t sleep for I live near the Polo Grounds, and the crowd began to gather there early in the evening of the day before the game to be ready for the opening of the gates the next morning. They tooted horns all night, and were never still. When I reported at the ballpark, the gates had been closed by order of the National Commission, but the streets for blocks around the Polo Grounds were jammed with persons fighting to get to the entrances.

The players in the clubhouse had little to say to one another. Merkle had reported as usual and had put on his uniform. He hung on the edge of the group as McGraw spoke, and then we all went to the field. It was hard for us to play that game with the crowd which was there, but harder for the Cubs. In one place, the fence was broken down, and some employees were playing a stream of water from a fire hose on the cavity to keep the crowd back. Many preferred a ducking to missing the game and ran through the stream to the lines around the field. A string of fans recklessly straddled the roof of the old grandstand.

Every once in a while some group would break through the restraining ropes and scurry across the diamond to what appeared to be a better point of vantage. This would let a throng loose which hurried one way and another and mixed in with the players. More police had to be summoned. As I watched that half-wild multitude before the contest, I could think of three or four things I would rather do than umpire the game.

The crowd that day was inflammable. The players caught this incendiary spirit. McGinnity, batting out to our infield in practice, insisted on driving Chance away from the plate before the Cubs’ leader thought his team had had its full share of the batting rehearsal. “Joe” shoved him a little, and in a minute fists were flying, although Chance and McGinnity are very good friends off the field. Fights immediately started all around in the stands. I remember seeing two men roll from the top to the bottom of the right-field bleachers, over the heads of the rest of the spectators. And they were yanked to their feet and run out of the park by the police.

I forgot the crowd, forgot the fights, and didn’t hear the howling after the game started. I knew only one thing, and that was my curved ball wouldn’t break for me.

Tinker started the third with that memorable triple which gave the Cubs their chance. I couldn’t make my curve break. I didn’t have anything on the ball.

I looked in at the bench, and McGraw signaled me to go on pitching. Kling singled and scored Tinker. The Cubs pitcher, Mordecai Brown, sacrificed, sending Kling to second, and Sheckard flied out to Seymour, Kling being held on second base. I lost Evers, because I was afraid to put the ball over the plate for him, and he walked. Two were out now, and we had yet a chance to win the game as the score was only tied. But Schulte doubled, and Kling scored, leaving men on second and third bases. Still we had a Mongolian’s chance with them only one run ahead of us. Frank Chance, with his under jaw set like the fender on a trolley car, caught a curved ball over the inside corner of the plate and pushed it to right field for two bases. That was the most remarkable batting performance I have ever witnessed since I have been in the Big Leagues. A right-handed hitter naturally slaps a ball over the outside edge of the plate to right field, but Chance pushed this one, on the inside, with the handle of his bat, just over Tenney’s hands and on into the crowd. The hit scored Evers and Schulte and dissolved the game right there. It was the “break.”

None of the players spoke to one another as they went to the bench. Even McGraw was silent. We knew it was gone. Merkle was drawn up behind the water cooler. Once he said:

“It was my fault, boys.”

No one answered him. Inning after inning, our batters were mowed down by the great pitching of Brown, who was never better. His control of his curved ball was marvelous, and he had all his speed. As the innings dragged by, the spectators lost heart, and the cowbells ceased to jingle, and the cheering lost its resonant ring. It was now a surly growl.

It was a glum lot of players in the clubhouse. Merkle came up to McGraw and said: “Mac, I’ve lost you one pennant. Fire me before I can do any more harm.”

“Fire you?” replied McGraw. “We ran the wrong way of the track today. That’s all. Next year is another season, and do you think I’m going to let you go after the gameness you’ve shown through all this abuse? Why you’re the kind of a guy I’ve been lookin’ for many years. I could use a carload like you. Forget this season and come around next spring. The newspapers will have forgotten it all then. Goodbye, boys.” And he slipped out of the clubhouse.