(L) Frank Sinatra lighting a cigarette, 1944. World Telegram photograph by Al Almuller. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. (R) Bing Crosby with golf balls during a World War II scrap rubber drive, 1942. National Archives, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library Public Domain Photographs, 1882–1962.

The first time I ever sang with a band was September 1972 in the dining hall at Princeton. The piano player gave me a four-bar intro, and I started in, “Without a song, the day would never end…without a song, the road would never bend,” when I felt a piece of cheese whirl past my ear. It seemed the crowd wanted to hear the Stones rather than Sinatra. I heard some clapping, the piano player gave me a wink, and I soldiered on to the end: “When things go wrong, a man ain’t got a friend…without a song.” I followed with Cole Porter’s “Night and Day,” this time with no cheese. At the end of the performance somebody booked our group for a party.

Something about singing the Great American Songbook that night with a band spoke to me, and I have been privileged to sing this repertoire professionally for more than forty years. So what is this Great American Songbook and what makes it so special?

No one is sure where the phrase comes from. The era of the Songbook is generally held to start in 1920 and end around the time of Oscar Hammerstein’s death in 1960. It consists of somewhere between three hundred and five hundred songs by a group of composers who often worked in teams and were mostly the children of Jewish émigrés. The songs were melodically simple and harmonically interesting, with a tight marriage between lyrics and melody. Romance was de rigueur.

There were certainly musical songwriting teams before this time (like Gilbert and Sullivan, where one wrote the music and other wrote the lyrics), but never so many: Rodgers and Hammerstein, Kern and Hammerstein, Rodgers and Hart, Dietz and Schwartz, Johnny Burke and Jimmy van Heusen. In this new era songwriters became stars and had their names displayed on marquees.

These writers came mostly from middle-class backgrounds and were highly educated—the kind of people who could have done anything. Lorenz Hart, Oscar Hammerstein, Richard Rodgers, and Arthur Schwartz went to Columbia; Cole Porter to Yale and Harvard. Dorothy Fields was an heiress; Hoagy Carmichael graduated from law school. They brought a depth of understanding to the marriage of their lyrics, melodies, and harmonic structures.

How did it all begin? It all started with the upright piano, which came into wide use in the nineteenth century. An upright was small, easy to transport, and much less expensive than earlier pianos. Tin Pan Alley, the collection of music publishers and songwriters centered on West Twenty-Eighth Street in New York City, also emerged late in the century, churning out crowd-pleasing pop songs. These tunes slowly replaced earlier standard fare, which had largely consisted of classical music and hymns. “Song pluggers,” employed by music publishers and department stores (many of them Jews newly arrived from eastern Europe, notably Irving Berlin and George Gershwin), promoted new tunes to be played on upright pianos and at all sorts of social occasions.

Throughout history much music has been financed by elite patrons—by royalty or the likes of the Medicis. But sales of Tin Pan Alley sheet music meant that the public financed new music directly. Strengthening copyright laws also gave songwriters and music publishers new protections, and resulting profits led to bigger budgets for promotion and marketing.

World War I fueled the boom in this new music. Before the war there was considerable resistance to America joining, and antiwar songs like “Don’t Send My Darling Boy Away” became big sellers. But the day after the U.S. declared war against Germany, George M. Cohan composed “Over There,” a simple patriotic march that anyone could sing. The cover of the sheet music was illustrated by Norman Rockwell and the song recorded by Enrico Caruso. Two million copies of the sheet music were sold, and Caruso’s recording moved one million records, an extraordinary amount at the time. The government formed the Committee on Public Information to drum up support for the war in 1917, and some 75,000 thousand speakers fanned out across the country to churches, town halls, bandstands, and gazebos to get out the message. Liberty Bond rallies were replete with marching bands and professional singers performing new songs like “Over There.”

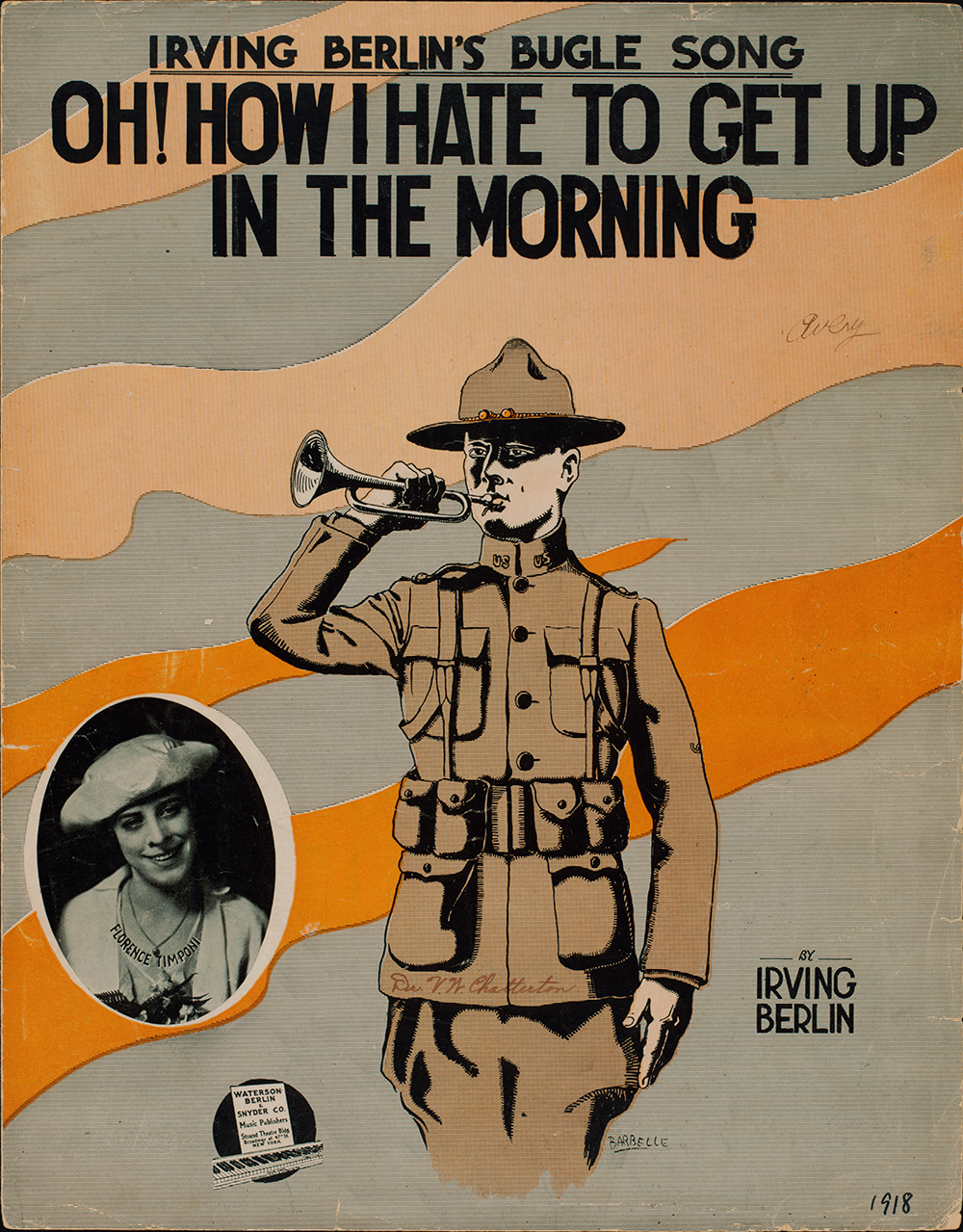

These tunes featured lyrics like “We’re all going calling on the Kaiser” and “If he fights like he can love, good night Germany.” The biggest hits of the era were by Irving Berlin, including “Let’s All Be Americans Now” and “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.” My great-grandmother ran the Red Cross in New York during the war and often told me of the stirring renditions of these tunes she heard there every night.

War lyrics did not reflect the realities of war but gave the impression that the war would soon end with a victorious American army returning home in glory. Patriotic songs about the war supplanted Irish, Italian, German, and English tunes passed down by immigrant relatives. Performance of previously popular Viennese operetta tunes faded quickly as Austria allied with Germany. The result was that there was, for the first time, an American songbook. Though some criticized it as propaganda, there is no question it played a major role in the development of an American musical ethos.

The end of the war was followed by Prohibition and women earning the vote in 1920. Paradoxically, alcohol consumption increased in the big cities, and speakeasies sprang up that often employed jazz bands. The broadening of wealth planted the seeds of youthful rebellion. My grandmother recalled Chicago debutante parties in the late 1920s where she danced the Charleston, originally an African American dance, to a swing band and smoked until well past midnight while her escort sported a hip flask. My grandfather in turn described dancing down the street in Miami Beach past a succession of art deco hotels with a different orchestra playing on the terrace of each. As the music changed from hotel to hotel, their dances shifted from a foxtrot to swing to cha cha.

Jazz bands helped promote the new standards. Generally, the melody was played through once and then deconstructed and played numerous times, variations limited only by the piece’s harmonic structure and by the imagination of the musicians and singers, often with a return home to the melody at the end. In 1927 Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer inaugurated the talkie era of movies, and it wasn’t long before there were singing dance films, followed by the Busby Berkeley extravaganzas along with the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films, which featured the music of Berlin, Kern, and Gershwin.

The Great Depression found the country engaged with popular music. With work scarce, Americans had the time and desire to be distracted by entertainment. Movies brought fantasy nationwide to millions who had never experienced Broadway theater. The Victrola record player became more affordable, and annual record sales went from ten million to fifty million. Large-scale radio broadcasts began in 1932 and led to the decline of the sheet music business.

And Americans wanted more than just to play a record at home or listen on the radio; they wanted to dance and see singers. America had by this time begun to listen and dance to swing music performed by larger ensembles that became known as big bands. These big bands were broadcast live across the country from ballrooms like Roseland, the Cotton Club, and the Savoy in New York and others in Chicago and Kansas City. The so-called Name Bands of the era included Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Woody Herman, and Artie Shaw. All toured extensively, and bandleaders became celebrities.

Familiarity is the sine qua non of a hit song. New technologies allowed the public opportunities to regularly hear songs through movies, radio, recordings, local clubs, and the new medium of television. An oft-repeated show business story tells of the Broadway critic who dismissed Jerome Kerns’ 1933 Roberta by saying “there’s no tune you can whistle when you leave the theater.” The score included “Yesterdays,” “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” and “The Touch of Your Hand.” All of these songs later became hits, fueled by the movies, radio, recordings, and television.

Bing Crosby was the first singer to add an intimacy to his recordings and performances with his microphone technique. Before amplification, singers had to virtually shout to be heard in live performances. Crosby, America’s most successful early crooner, dominated the airwaves, and he became the best-selling recording artist of the twentieth century. His most successful single remains his recording of Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas,” which sold over 100 million copies.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, American men went off to war while the big bands lifted morale on the home front. Many band members were called up, however, which meant there simply weren’t enough performers to fill big-band stages. An ill-timed recording strike in 1942 worsened the situation.

The big-band format had been a full instrumental chorus or two of the band while the singer sat until he was called upon to stand and finish the song with a vocal. Singers played second fiddle to the bandleaders. Frank Sinatra changed all of that.

Sinatra had begun to make his mark on the music world in 1939 with big-band leader Harry James, before moving on to Tommy Dorsey. In July 1940 Sinatra and Dorsey had a number one hit with “I’ll Never Smile Again.” In 1942 Sinatra’s music was broadcast on the live radio show Your Hit Parade, sponsored by Lucky Strike cigarettes. The bobbysoxers—as his female devotees were called for their rolled-to-the-ankle white socks—were swooning in the aisles for young Frankie. Sinatra’s vast appeal to this group, whose husbands and boyfriends were off fighting and who now had disposable income from working during the war, revealed a new audience demographic for popular music. Sponsors had previously not recognized the vast buying power of these mostly female teenagers and young adults.

Sinatra played his first solo concert in December 1942, with as many as 35,000 bobbysoxers trying to get into the Paramount Theater in Times Square. He performed to shrieks from five thousand teenage girls, who refused to vacate to let others in for the next show and had to be dragged away while attempting to rush the stage. No matter that Sinatra’s managers had supposedly hired the first group of girls to rush the stage; Sinatra was the country’s first “rock star” and displaced Bing Crosby as America’s number one crooner. In 1943 Columbia Records rereleased the 1939 recording of “All or Nothing at All” by the Harry James Orchestra with Frank Sinatra. Before Sinatra had been listed only in small print, but this time he had top billing (“accompanied by the Harry James Orchestra”), and the record became an instant hit.

Following the war Broadway entered its golden era with Rodgers and Hammerstein cranking out hit after hit and Cole Porter penning a number of hit musicals. The songwriters of the postwar era were talented and charismatic and joined by a new generation of arrangers, including Nelson Riddle, Billy May, and Don Costa, whose masterful orchestral creativity cannot be overstated. Just listen to Riddle’s brilliant arrangement of Gershwin’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” sung by Sinatra: by employing his signature trombone section, he plumbs the depths of an obsessive personal relationship via a number of crescendos and diminuendos.

The Great American Songbook was firing on all cylinders. A show would open on Broadway, and then the best song or two would be sung live on television and radio. A singer would record the song, which would then be played on the radio and performed at high-profile nightclubs in Vegas. The song would then be reprised on various television shows. And then the cover versions would come out, and you would start to hear the song played in corner bars and cabarets.

In thirty-five years of singing with my band, the most requested song—and the one I love to sing the most—is a song from this era. “Mack the Knife” was from a German opera, with lyrics by Bertolt Brecht and music by Kurt Weill, about a murderer. Bobby Darin transformed it by adding a driving swing beat to it, a progressive series of modulations. It had a surprise ending with only the drums and Darin belting out the catchy phrase “look out ol’ Mackie is back.” It is considered by many to be perhaps the quintessential American hit of the Great American Songbook era.

So when did it end? Many say it was with the arrival of the Beatles in the 1960s. Perhaps the decline began with the debut of Elvis in the 1950s. The number of radio plays for the standards that make up the Great American Songbook had started to drop beginning in the late 1940s. There was a growing acceptance by white radio audiences for what had previously been called race music, which was rhythm and blues, and was now called rock and roll and played by white performers.

The Great American Songbook had a run of at least forty years. Just as the music of Brahms, Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven will always have a special place in American concert halls, I think the Great American Songbook will continue to be performed and periodically revived. Lady Gaga’s duets with Tony Bennett and Justin Timberlake’s fling with big band have recently brought the music to a new audience. And dance orchestras like mine, now in its fortieth year, perform everything from Gershwin to Gaga and Berlin to Beyoncé. As Vincent Youman wrote in 1929, in that first song I sang at Princeton, “I only know / there ain’t no love at all / without a song.”

Explore Music, the Fall 2017 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.