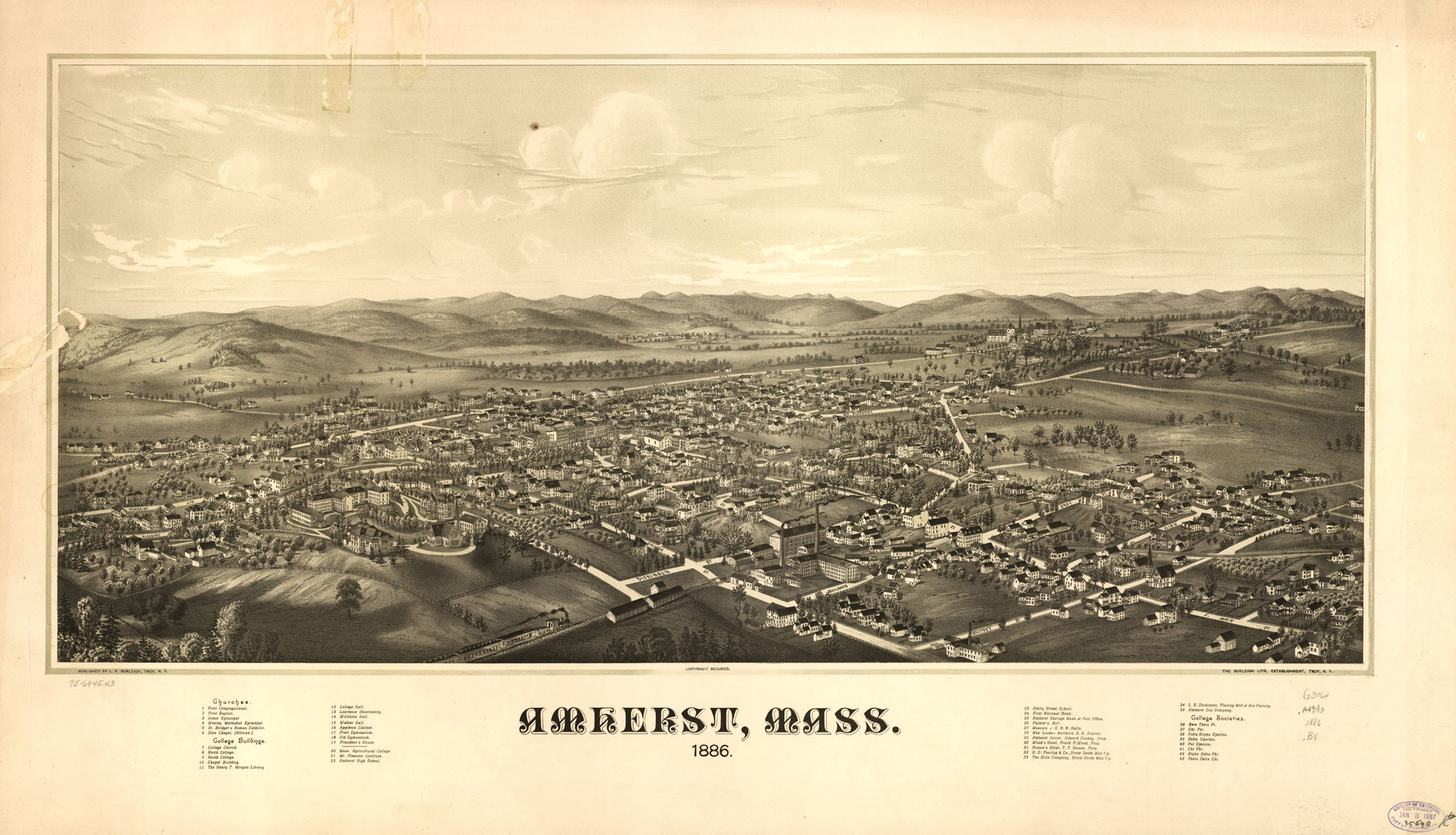

Bird's-eye view of Amherst, Massachusetts, by L.R. Burleigh, 1886. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Mabel Loomis Todd was back in Amherst by January 26, 1882. Her social activities picked up right where they had left off, and continued to revolve mostly around spending time with members of the Dickinson family. Her diaries depict many days of going over to The Evergreens for piano practice (often for hours at a time), and also for social outings. Mabel wrote, “I have been at Mrs. Dickinson’s a great deal since my return, and she admires me extravagantly and praises me to Ned and Mattie as a sort of model for them. She appreciates me completely, and I love and admire her equally. She is a rare woman, and her home is my haven of pleasure in Amherst.”

Within the next couple of months two events would prove to be significant turning points in Mabel’s relationship with the Dickinson family and, ultimately, in her life.

The first came on February 8, 1882. A brief entry in Mabel’s diary read, “Went in the afternoon to Mrs. Dickinson’s. She read me some strange poems by Emily Dickinson. They are full of power.”

It is the first mention of Emily or her poetry in any of Mabel’s writings. At the time, fifty-two-year-old Emily Dickinson had already written the majority of her eighteen hundred or so poems; contemporary analysts believe that many of the poems she wrote during this period of her life were less “finished” than earlier ones. Yet despite the prodigious output of poetry, few people were aware of its existence. Mabel became one of the few people outside of Emily’s family and some of her friends who knew that Emily wrote poetry. Sue Dickinson, wife of Emily’s brother Austin, was also aware of her sister-in-law’s talents. During her lifetime, Emily shared at least 250 of her poems with Sue, and Sue offered Emily her comments and editorial suggestions on some of them. It might have been Sue who submitted a number of Emily’s poems to newspapers; between 1850 and 1866, ten of her poems were published anonymously. Three of Emily’s poems were published in 1864 in a short-lived publication called The Drum Beat, edited by Amherst College alumnus Richard S. Storrs, and another appeared in The Round Table, edited by fellow Amherst graduate Charles Sweetser. It is unclear exactly through what networks the poems were contributed and whether Emily knew that they had been published.

Author and poet Helen Hunt Jackson, who grew up in Amherst and was a childhood acquaintance of Emily’s, was another in the small circle of people who knew that she was a poet. Helen got Emily to agree to contribute one of her poems to a volume of edited but unattributed poetry entitled A Masque of Poets (1876), and subsequently wrote to Emily in a letter that it was wrong for her not to share her great talent with the world. Thomas Niles, who had published the book, attempted to convince Emily to allow him to bring out a collection of her poems, but she demurred. And in 1880 some representative of a charity in Amherst, possibly tipped off by Sue Dickinson, tried to persuade Emily to donate some of her poetry to a book whose profits would “aid unfortunate Children”; apparently Emily did submit several poems for consideration but it is not certain whether they were published.

Mabel’s instant recognition that Emily’s odd poems that defied contemporary poetic conventions were “full of power” would become a key to one of the most significant endeavors and accomplishments of her own life, as well as the basis for the complex relationships that she—and her young daughter Millicent—would have with the Dickinson family.

Throughout February into March, Mabel’s diaries continued to note the many times that she spent at the Dickinsons’ home, or went out for moonlit sleigh rides with Ned, Austin and Susan’s oldest son, or danced with him, or times he came to call on her. She often noted that “we had a jolly time” or “Ned is very lovely to me” or “excellent waltz with Ned.” In mid-March, Mabel was invited to a grand event at the home of Amherst College president Julius Seelye, at which she had been asked to play several piano pieces. Mabel wrote that the prospect of playing in front of a significant audience of “the most important people” made her somewhat nervous and that “I wore Ned’s Alpha Delta pin.” For Mabel, Ned became a companion, or as she sometimes referred to him in her diaries, a “knight errant,” who could escort her to social events “whenever David”—her husband—“could not attend me.”

But for Ned, it appeared to have meant much more. At twenty years old, he led a somewhat sheltered existence. He was not as quick-witted as either of his parents or his siblings. Yet as scholar Barton Levi St. Armand points out, Ned was nonetheless clever in his use of language and absolutely dedicated to his family, especially his beloved mother, two siblings, and his aunt Emily. Though a sophomore at Amherst College, Ned had a kind of “special student” status in which he did not take a full course of study and received no grades.

Ned also had epilepsy. The disease’s onset came when he was fifteen, and both Sue and Austin sought to shield him from it. In the nineteenth century, epilepsy was not well understood and heavily stigmatized. Those with epilepsy were marginalized and feared. Marriage was discouraged for fear of passing the disease along to offspring. The shame associated with epilepsy often caused people with the malady—or their family members—to hide it. (Emily Dickinson biographer Lyndall Gordon asserts that Emily herself also suffered from epilepsy. Though it is true that a tendency for epilepsy can be genetically linked and run in families, Gordon’s hypothesis, based both on historical records of doctors’ visits, medications, and symptoms, as well as interpretations from Emily’s poetry, is highly controversial among Dickinson scholars. Unlike her nephew Ned, whose parents left detailed accounts in their diaries delineating his epileptic seizures, there is no similar record for Emily.)

It was Austin who cared for Ned during his “fits,” which tended to occur at night, and his diaries note the many times he would go to his son’s room after a terrifying scream alerted his parents to another seizure. In Millicent’s readings of Austin’s diaries, entrusted to Mabel and saved after his death, she noted Austin’s descriptions of Ned’s “fits,” how they were often so violent that he described them as “an earthquake that shook the house.” Sue, too frightened to be helpful, left Austin to deal with their son. This clearly became a source of tension in the marriage. Neither Austin nor Sue ever told Ned about what occurred, though it is difficult to believe that Ned never realized the issue himself. Austin believed that his son’s illness emanated from Sue’s several attempts to abort him when she was pregnant—at least, according to what he later told Mabel, who passed this theory along to Millicent, who dutifully recorded it in the notes she took for Mabel.

Perhaps out of guilt or perhaps out of a sense that she needed to overcompensate for her eldest child, who wasn’t quite on par with his peers, Sue Dickinson did all she could to arrange Ned’s social engagements. Part of this included encouraging him to escort Mabel about town. She certainly never imagined that this relationship would be anything other than instructive and convenient for her beloved son.

But Ned fell in love with Mabel. Undeterred by the five-year age difference, unconcerned about the impropriety of it all, and indifferent to the fact that she was married and had a young child—to say nothing of the fact that he spent time with and respected Mabel’s husband David—Ned was soon head over heels. “Dear Madame Valentine,” he wrote her on February 14, 1882, “Would you do me the great honor to drive a little while avec moi this afternoon at half past four. With hope, Sam Weller. p.s.—Never sign a valentine with your own name!” (The name Ned penned, in fact, belongs to a character from Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers, who sends a valentine to a woman with whom he fell in love at first sight.)

And Ned’s passion for Mabel seemed only to intensify. “My dear Desdemona,” he wrote her two months later. “Now you are gone & Amherst has fallen and great was the fall thereof. No longer shall the sweet tones of your voice be heard in the land; the piano keys are still in mute appeal for the hand that wrought such marvelous melody from them. The sprite has sailed away to warmer climes but she has left something which can never part—abundant food for thought, sweet, sweet thought…Give my love and missing to Mr. Todd…I can’t send it to you for you have it all.”

“Indeed, I think it will not hurt Ned…that he worships the very ground I walk on,” Mabel suggested in her journal. “He is only a boy—only 20—but he is the most graceful host in his own home that I have ever seen. And he is so very manly and careful of his sister, and he is simply devoted to his mother…He looks so helplessly at me and said he never experienced any such feeling before that he does not know how to regard it, and he knows he is unsettled and inattentive to his studies and thinking of me every moment…I could twist him around my little finger, that he would go off and kill somebody if I bade him,” she gleefully concluded. For Mabel, Ned’s attentions were likely an affirmation not only of her own allure and magnetism but also of her ability to attract a man who was a member of the kind of aristocratic, educated, artistic, and wealthy family she most coveted.

“I have nothing but romances to write of myself,” she reflected in her journal. “As soon as I put distance between myself and one romance, another one comes to me. It’s odd, but I do like it intensely.”

Excerpt adapted from After Emily: Two Remarkable Women and the Legacy of America’s Greatest Poet by Julie Dobrow. Copyright © 2018 by Julie Dobrow. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.