Au miroir d’un art nouveau (In the Mirror of a New Art), by Camille Claudel, 1899.

The ground-floor apartment at 19 quai Bourbon, on the Ile de St. Louis in central Paris, was unlike anything the two hospital wardens had ever seen. Amid filth and clutter, dried-out clay, and a festoon of spider webs was not furniture, save for one broken and torn armchair, but sculptures. Weaving through the squalor were more cats than you could count, while the fourteen Stations of the Cross—the series of images depicting Christ on the day of his crucifixion—had been cut out of a newspaper and pinned on the wall. Elsewhere wallpaper hung down in strips. To deter intruders, the shutters and blinds were kept closed, and security chains were in place.

But on that Monday morning in March 1913, the intruders—two strapping men from the Ville-Évrard mental asylum just outside the city—forced their way in. The sobbing and terrified resident was physically removed, bundled into a waiting vehicle, and driven away. Her captors probably neither knew nor cared that the disheveled woman in their charge, forty-eight-year-old Camille Claudel, was a renowned sculptor—even, in the eyes of some, a genius. Around the turn of the century, at the peak of her career, she exhibited work at the most prestigious salons and galleries and was applauded by critics.

To take just one example: a plaster of La Petite Châtelaine (1893–95), Claudel’s bust of a little girl, was acquired by the Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts, an organization set up to bring fine art to mass audiences. Completed over two summers at Chateau de l’Islette in the Loire Valley—the model was the chateau owner’s granddaughter—the sculpture’s unsmiling face with its thoughtful, questing expression is an impressive feat from an artist who was barely thirty. “Mademoiselle Claudel’s bust is endowed with the intense and inspired radiance of young life,” praised the journal Revue Encyclopédique. A bronze casting was bought and donated to the Musée Joseph Denais, in Beaufort-en-Vallée, by financier Baron Alphonse de Rothschild, an art collector and member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

In July 1913, a few months after Claudel’s summary removal from society, a marble version of La Petite Châtelaine, belonging to the industrialist Henri Fontaine, was featured in L’Art Decoratif. The magazine had dedicated a special issue to Claudel’s work, which appeared with commentary from her younger brother, the poet and diplomat Paul Claudel. In reaction, the newspaper L’Avenir de L’Aisne ran an impassioned polemic, stating: “This astonishing artist, battered repeatedly by cruel destiny, was still waiting for the moment when tardy justice would make her the equal of the greatest plastic artists. Thanks to L’Art Decoratif, this moment has arrived.” Yet, as the article goes on to say, Claudel was in no position to appreciate the tribute. She was not merely locked away but—at the behest of her family—sequestered, cut off from all contact with the outside world including letters. She was not told the terms of her sequestration, leaving her to wonder why no one ever replied to her letters or came to see her.

In accordance with the 1838 French “lunacy law,” all that was required for Claudel’s committal and sequestration was a medical certificate, written and signed by a doctor—in her case, a neighbor on the quai Bourbon—at the request of a family member. Camille’s father, Louis-Prosper, who always supported and protected her, had died a week earlier. After the funeral, with what seems like indecent haste, Paul sought the certificate declaring his sister insane. The evidence given for Camille’s “very serious mental disorders” included “that she wears wretched clothes; that she is extremely dirty since she never washes; that she sold all her furniture,” and “that for the past several months she has not gone out during the day, but sometimes comes out in the middle of the night.”

Their mother, Louise, willingly cosigned the certificate. Mother and daughter had never gotten along: the emotionally repressed Louise preferred her younger daughter and middle child, also called Louise and far more conventional and obedient than the rebellious Camille. Paul and Camille, the geniuses of the family, were very close growing up—“my little Paul,” she called him—and encouraged each other’s artistic dreams. Possibly the siblings’ previous intimacy, and their similarity, made Camille’s mental deterioration all the more frightening to Paul. “I am exactly like my sister,” he once remarked, “although more of a weakling and a dreamer and, without God’s grace, my story might have been hers or even worse.”

Stunned and distressed to be torn away from her home and work, Claudel prayed that the incarceration would be short-lived, though she feared otherwise. “If you wish to come and see me,” she wrote to her cousin Charles Thierry a few days after arriving at Ville-Évrard, just before the sequestration order was given, “you can take your time, because it will be long before I get out of here; they have me and they are not going to let go.” They did not. Thirty years later, she died in a second institution, never having tasted freedom, nor touched clay, ever again.

In the wake of Claudel’s committal, there was an outcry in the press. She was of sound mind, it was claimed, and holding her against her will was an affront to morality. “There are two ways of eliminating a person from society,” declared a letter published in the newspaper Grand National. “The first is murder. The second way is legal committal, later converted, according to needs, to sequestration.” Fiercely condemned for using an antiquated law to get rid of an embarrassing and inconvenient family member, Paul was urged to make a statement. “Considering the circumstances,” wrote a journalist for the Grand National, “it is up to him to stop the odious sequestration.” Paul’s position as consul-general in Hamburg made any public rebuttals impossible, but he deemed all accusations against him slander—which was “fine,” he wrote in his journal. “I’ve received so much undeserved praise that slander is refreshing and good, it’s the lot of a Christian.”

Paul genuinely believed there was no possibility of Camille fending for herself any longer. Since she rarely went out, and refused to open her front door, food had to be delivered through a window. And she had a long-standing habit of smashing all her completed sculptures with a hammer every summer. The result, said a friend who visited her in 1905, was “a pathetic spectacle of ruin and devastation.” Her neighbors complained about the state of her apartment, always barricaded shut but known to be hazardous and filthy inside. Most seriously, Claudel suffered from persecution mania, insisting that conspirators plotted against her, stole her creative ideas, and even drugged her. Paul, a devout Catholic, had at one time suspected a demonic possession and asked a priest if an exorcism could be conducted “from afar.” Decades later, he regarded Camille’s involuntary commitment as appropriate punishment for an abortion she had undergone, probably in her late twenties. “She has been paying for it in a house for the insane for 26 years,” he wrote to a friend. “To kill a child, to kill an immortal soul, it is horrible!”

Paul also blamed the ruination of his sister’s life on her longtime lover, mentor, and collaborator, the sculptor Auguste Rodin, deeming their breakup “a total, profound and definite catastrophe…She had bet everything on Rodin, she lost everything with him.” When it came to Rodin, however, Paul was far from objective: for supplanting his centrality in Camille’s life, and initiating her into sin, Paul hated the older man with a passion.

It was true that Claudel’s relationship with Rodin, which spanned close to fifteen years, in many ways eclipsed her own identity. To the art establishment, she was always Rodin’s protégée, even as her work equaled and arguably exceeded his in merit—if not, inevitably, in volume. In the years leading up to her committal, Rodin haunted her thoughts, becoming the primary focus of her persecution complex. “At this moment,” she wrote to Thierry in early 1913, “M. Rodin has persuaded my relatives to have me locked up. They are all in Paris because of that. The scoundrel will then, as a result of this suit, take possession of my life’s work.”

In reality, Rodin played no part in her committal and was horrified when he heard about it. Yet in Claudel’s troubled mind, he was a spectral ogre who represented every challenge and disappointment life had thrown at her: the chauvinism of a society in which a woman could not be free and independent, let alone a great artist; the French government, whose official commissions could make or break an artist’s career, yet were doled out and withdrawn for political or nepotistic reasons; the family life she was denied when Rodin refused to marry or raise children with her (biographers are uncertain about Claudel’s pregnancies, but there were rumors that she gave birth at least twice).

When Claudel met Rodin she was in her late teens, an ambitious and committed artist sharing a studio in the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs in Montparnasse, near the Luxembourg Gardens, with three English women. Claudel “was the guiding spirit of the group,” explained Mathias Morhardt, a journalist and friend who published a laudatory article about her in Mercure de France in 1898. “She chose the models, she indicated the pose, she assigned the tasks, she decided the seating arrangements.” While attending a private art academy (women were barred from attending the elite École des Beaux-Arts), Claudel had arranged for Alfred Boucher, the young sculptor and future patron of Chagall and Modigliani, to visit her studio each week as an adviser. Boucher hailed from a village near Nogent-sur-Seine, a town sixty-two miles southeast of Paris where the Claudel family lived between 1876 and 1879. As an adolescent, Claudel was already sculpting heads and figurines, and the Nogent community was small enough that her precocious gift soon came to Boucher’s attention. He began guiding the unusual girl’s career and encouraged the move to Paris, where he introduced her to the painter and sculptor Paul Dubois, who was the director of the École des Beaux-Arts (and also came from Nogent). On seeing Claudel’s clay studies, Dubois remarked, “You took lessons with Monsieur Rodin!” Claudel had never heard of Rodin, but their paths were about to cross.

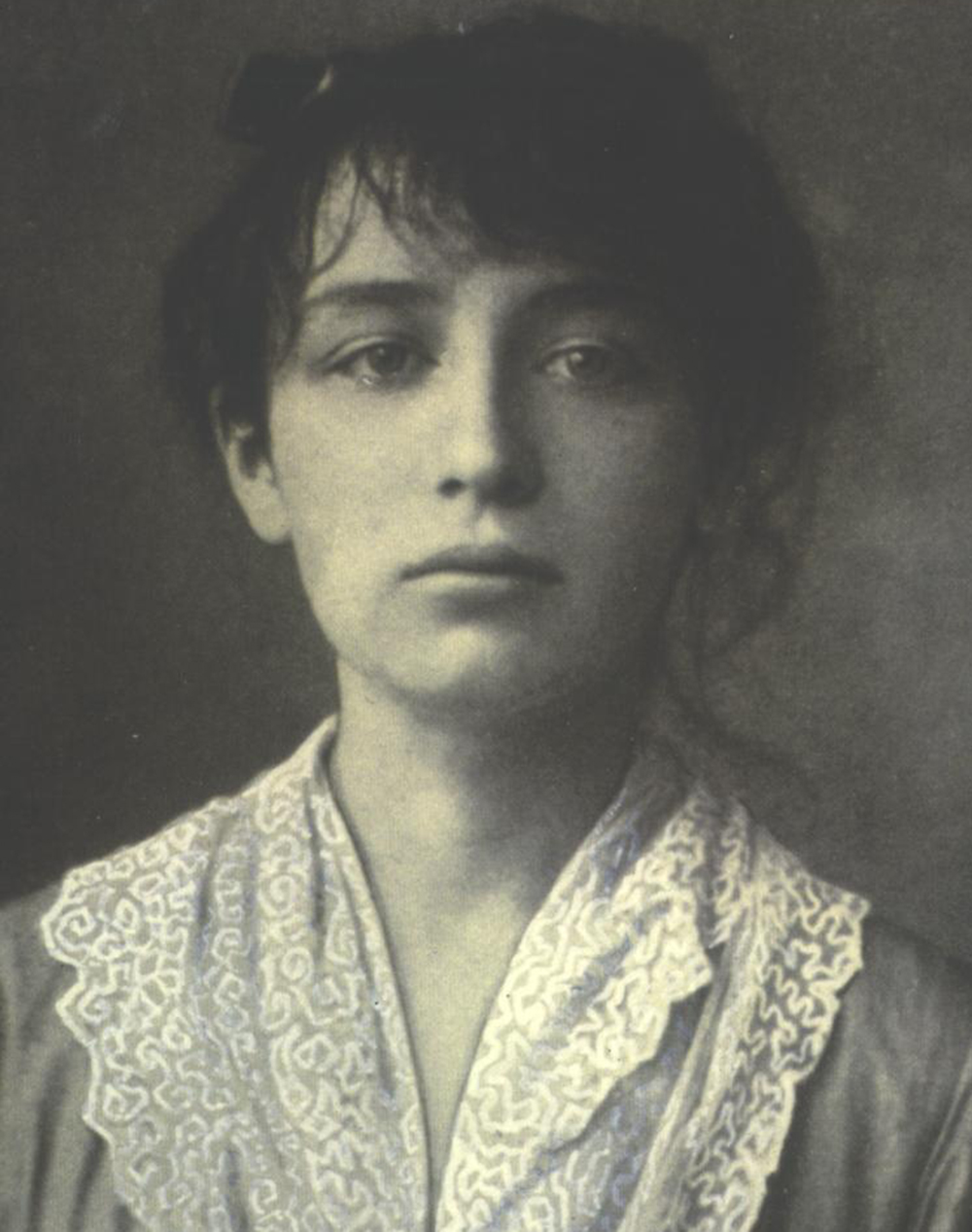

When Boucher won the Prix de Salon, allowing him to spend six months in Florence, he asked Rodin to take over his supervisory role in the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. Rodin, twenty-four years Claudel’s senior, was instantly struck by her blazing talent, her frank personality, and her gamine beauty. A photograph of Claudel at twenty, in which she is gazing defiantly at the camera, captures what Paul, as an elderly man, remembered as her “impressive air of courage, directness, superiority, gaiety. One who was endowed with much.” Rodin’s common-law wife and the mother of his son, Rose Beuret, lived in the country, which freed him to enjoy various superficial trysts in Paris. But unlike the models he usually dallied with—and Beuret, who was uninterested in art and ideas—Claudel was, he felt, his soulmate both romantically and artistically. With her he discovered, in the words of Morhardt, “the happiness of always being understood, of always being exceeded in his expectations. As he himself said, it was one of the great joys of his life.”

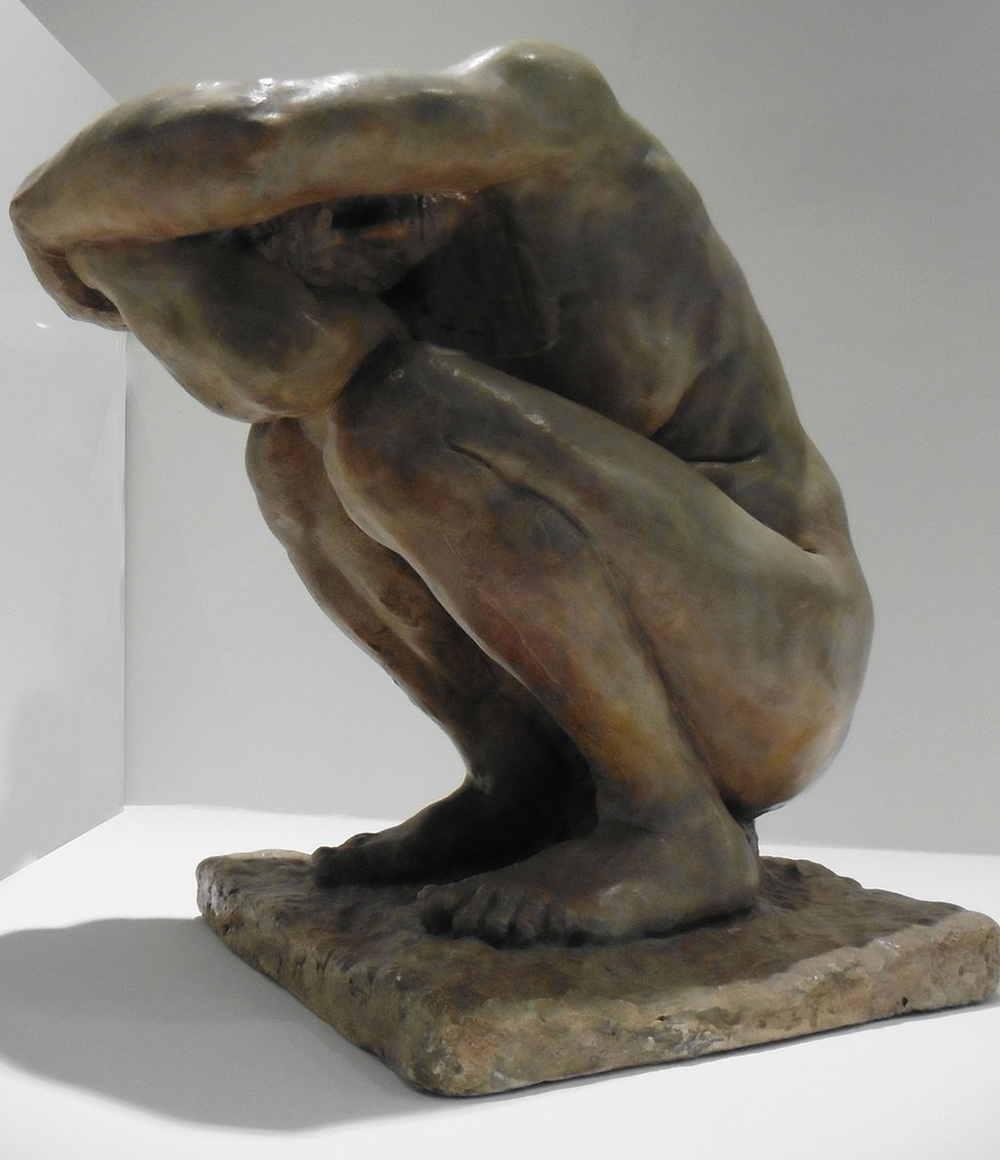

Before long, Claudel was the principal assistant-disciple at Rodin’s studio in the rue de l’Université in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. He came to rely on her skill as a sculptor, and she was trusted to work on such celebrated large-scale works as The Gates of Hell, which depicts a scene from Dante’s Inferno, and The Burghers of Calais, a commemoration of French heroism during the 1347 siege of Calais. Claudel also sat for Rodin, lending her face and body to Danaïd (1885–89), inspired by the Greek myth. A naked figure curled facedown in despair, the sculpture symbolizes the eternal punishment given to Danaos’s fifty daughters for murdering their husbands: filling a perforated barrel with water. La Pensée (The Thought, 1896), a study of Claudel’s head emerging from an unfinished block of marble—a prophetic emblem, it now appears, of being stuck or buried alive—is one of several direct portraits of her that Rodin reworked and reconceptualized long after she had left him.

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, Claudel and Rodin lived and worked together at his studio in the 13th arrondissement, La Folie Neubourg, a crumbling eighteenth-century mansion set amid a wild overgrown garden. As well as collaborating on Rodin’s pieces, during this period Claudel also created many significant sculptures of her own. A plaster of L’Abandon (1888)—in which a kneeling man reaches up to embrace, as if in supplication, a standing woman who bends her neck to hear his pleas—won an honorable mention at the Salon des Artistes Français. In 1892, after completing La Valse (The Waltz), an entwined nude couple whose diagonally angled bodies evoke ecstatic movement, Claudel applied for a state commission to produce the piece in marble. An inspector from the Ministry of Fine Arts described La Valse as “a virtuoso performance…Rodin himself could not have studied with more artistic finesse and consciousness the quivering life of muscles and skin.” Nonetheless, the inspector rejected Claudel’s application, balking at the raciness of the composition and “the closeness of the sexual organs,” especially coming from a woman artist. Admiring critics had no such qualms. “I don’t know where they are going,” marveled Octave Mirbeau, “to love or to death.”

But it was the period following Claudel’s split from Rodin, sometime in 1893, that was the most artistically fruitful of her life, contrary to Paul’s belief that the separation was the sole and immediate catalyst for her downfall. She was not, after all, the abandoned one, but the one who walked away and broke Rodin’s heart. “Rodin was unhappier without Camille than with her,” writes Paul’s granddaughter Reine-Marie Paris in her biography of Claudel. “Those who knew him at the time were witnesses to the anguish he suffered over the separation, an anguish that lasted until his death.”

Even at the beginning of their relationship, Claudel did not seem to feel true romantic passion for Rodin, much to his despair. “Frankly, there are times when I believe I will forget you,” he wrote in an early letter. “But, in an instant, I feel your terrible power. Have pity, cruel girl. I can’t go on. I can’t spend another day without seeing you. Otherwise the atrocious madness. It is over, I don’t work anymore, malevolent goddess, and yet I love furiously.” According to Paris, Claudel’s affection for Rodin was “tempered and quite rational—almost calculating insofar as her own ambitions were concerned.” Still, the stigma of being a mistress was monumental—and for Claudel, a cause of strife in her family. Paul deeply disapproved of the relationship, and to their mother, there was little difference between mistress and prostitute. For a young woman to be a sculptor was outlandish enough, but to live brazenly with a man outside of marriage was beyond the pale. So it was only natural that Camille sought marriage to Rodin as a means of legitimizing her existence, reconciling her artistic vocation with the conventional expectations of bourgeois French society. Eventually, though, she tired of waiting for that opportunity to materialize. At age twenty-eight, she turned her back on sex and romance for good, instead dedicating herself to her work and embracing her status as an eccentric.

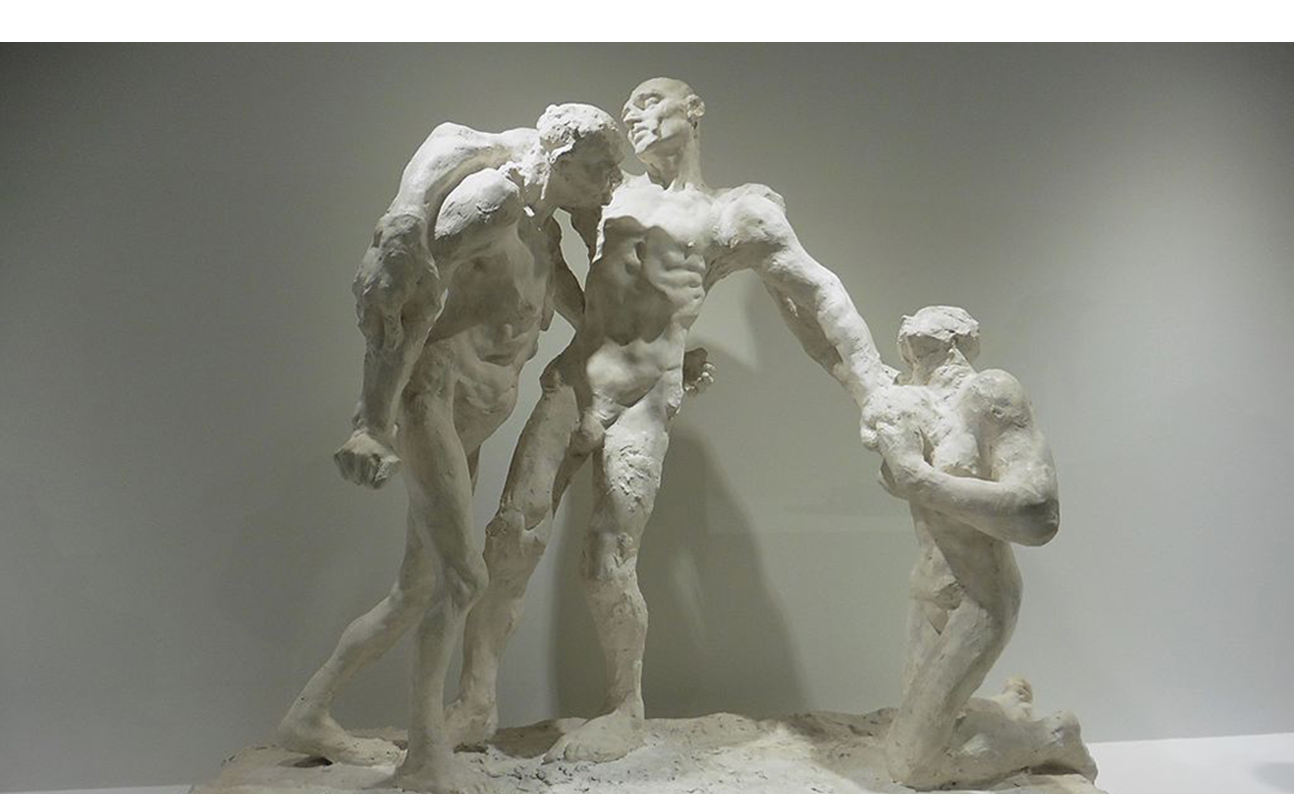

In 1895 Claudel received her first state commission: a plaster of L’Âge Mûr (The Age of Maturity), a statuary group that explicitly represents the love triangle between Claudel, Rodin, and Beuret. A man is pulled between two women: one, youthful and beautiful, is kneeling and reaching out an imploring hand, while the other, old and dominant, has her large restraining hands around the male figure’s upper arms. The Ministry of Art inspector commented, with an air of surprise, “It really is, from a woman, a very noble and thought-out work.”

L’Âge Mûr was exhibited in 1899 at the salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where it was seen by Rodin for the first time. The inspiration for the work was obvious, and he was appalled and insulted by such conspicuous exploitation of his personal life. (Paul was also shocked by it. “This young naked woman,” he wrote. “That’s my sister…Imploring, humiliated, on her knees and naked!”) An additional state commission to create a bronze casting of the piece was soon revoked, and the following year the plaster was rejected as an exhibit at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Claudel—almost certainly correctly—blamed Rodin for both setbacks. They had remained on good terms for the first few years after their romantic and professional parting, when Rodin had helped his former protégée in any way he could. But from that point on, writes Claudel’s biographer Odile Ayral Clause, “Rodin stopped supporting Camille’s work, and she, for her part, started to view him as a villain intent on destroying her.”

Claudel, ever dogged in the face of challenges, persisted. In 1900 she began working with the gallerist and dealer Eugène Blot, who became a loyal friend and, during a time of almost constant poverty, one of her few financial resources. Without expecting much of a return on his investment, he purchased her work, including a piece he said was her favorite: a twenty-one-inch-high bronze of a nude girl playing the flute (La Joueuse de flûte, 1905). He also petitioned the government to award his client commissions and exhibited her work in two separate shows at his gallery, in 1905 and in 1908; the latter was the last one held in her lifetime. By then, she was succumbing to irrational fixations and anxieties, convinced that Rodin and his circle were out to get her, to steal her work or even kill her. “That pathetic specimen of a man uses me in all sorts of ways and shares with his pals, the chic artists, while they in turn get him decorated, give him ovations, banquets, etc.,” she wrote to Paul. “The ovations of this famous man have cost me an arm and a leg and I get less than nothing!”

An artistic genius whose talent was undervalued, a single woman without money or social status, and a resolute nonconformist in a culture that punished women who moved even slightly outside accepted norms, Claudel could not beat the odds stacked against her. She became a recluse, refusing invitations with the excuse that she had nothing to wear. “I am like…Cinderella,” she wrote to Blot, “condemned to stay by the ashes of the chimney without the hope of ever seeing the Fairy Godmother or Prince Charming arrive to turn my rags into fashionable dresses.”

She was also, by this time, all but estranged from her family. Paul lived overseas on various diplomatic postings, while her mother wanted little to do with the daughter who had disgraced the family name. Claudel’s sister, Louise, took their mother’s side. The elderly Louis-Prosper Claudel was, as ever, sympathetic to Camille, and sent money to her behind his wife’s back. But then he died—and Paul, who had a family of his own to worry about, not to mention a career that kept him far from Paris, was unable to bear the responsibility of his mad sister alone. Nor could he leave her to fester in those squalid rooms, where without psychological help, or the support of friends and family, her condition would surely deteriorate. “In view of this situation,” writes Clause, “committal could hardly be avoided. However, there is a significant difference between regular committal and sequestration.” Since Claudel had never attempted suicide or displayed violence toward others, the only reason for her sequestration was to keep the whole matter a secret and thus avoid—unsuccessfully, as it turned out—a dreadful scandal.

In September 1914, after the outbreak of war, Claudel was transferred from Ville-Évrard to the Montdevergues asylum near Avignon in Provence. Her continued heart-wrenching appeals to be released were ignored by Paul—who nonetheless occasionally visited her—and her mother and sister, who never did. Over the years, Claudel’s caregivers reported, she became quieter and more docile, a threat to no one. In 1920 the asylum doctor proposed that she be discharged on a trial basis. “Mademoiselle Claudel is calm,” he wrote to her mother. “Her persecution ideas, though not completely gone, are much less pronounced. She would very much like to be with her family and live in the country. I believe that, in these conditions, we could try to let her out.” Madame Claudel refused. Then in 1929 Jessie Lipscomb, one of the English women who had shared the rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs studio in the 1880s, found her way to Montdevergues. The two long-lost friends sat and talked for the first time in decades. Claudel was not insane, Lipscomb insisted afterward. Instead she was stuck in a kind of living death. “I have fallen into a void,” she wrote to Blot. “I live in world that is so curious, so strange. Of the dream that is my life, this is the nightmare.”

Claudel’s unjust internment was the first of several false deaths. The next was the widespread belief that she had died in 1920, a date that wound up in several reference books, most recently a 1976 dictionary of artists. When she actually died, in 1943 at the age of seventy-eight, her funeral was attended by no family or friends, only some nuns. She was first buried in a section of the cemetery reserved for the asylum, then later transferred to an anonymous public grave, making it impossible to bring her body to the family tomb—truly falling, as she put it, into a void.

And yet Claudel, or at least her place in the artistic canon, has had several resurrections as well. Eight years after her death, the Musée Rodin in Paris held a retrospective of her work, exhibiting forty pieces. The public paid little attention, however, and she slid back into obscurity for more than thirty years—until 1982, when a novel based on her life, Une Femme by Anne Delbée, caused a renewal of interest in Claudel’s life and career. In 1984 the Musée Rodin held a major exhibition of her work, drawing crowds and sparking international publicity. A film adaptation of Reine-Marie Paris’ 1984 biography, starring Isabelle Adjani as Claudel and Gérard Depardieu as Rodin and directed by Bruno Nuytten, came out in 1988. That same year, a high-profile exhibition was organized by the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC.

The current decade has ushered in another Claudel renaissance. In 2013 Camille Claudel 1915, directed by Bruno Dumont and starring Juliette Binoche, premiered. The film, which depicts the artist at Montdevergues as she waits for a visit from Paul, won several international film festival prizes. In 2014 Claudel entered, at number seven, Artnet.com’s list of the ten most-expensive women artists at auction. La Valse—the sculpture of the waltzing couple that the French government found too indecent to commission—had sold for £5 million at Sotheby’s London the previous year. In the most recent list, published in May 2016, Claudel was at number nine, between Frida Kahlo at ten and Tamara de Lempicka at eight.

On March 26, 2017 the Musée Camille Claudel opened in Nogent-Sur-Seine with a collection of more than three hundred pieces, including around seventy by Claudel, as well as some by Rodin, Boucher, Dubois, and other French sculptors of their era. It feels fateful and a little cruel that the museum, long in the making but beset by obstacles and delays, is now launching in the centenary year of Rodin’s death, with all its inevitable hoopla. For Claudel longed, above all, to escape his shadow, to be recognized as an artist with her own distinct and original style. In 1893, when she had begun working alone, she shared some of her sketches and ideas with Paul. “You see,” she explained, “it’s no longer at all like Rodin.” Years later Paul, as brilliant a poet as his sister was a sculptor, expressed the magic of a Claudel in words that cannot be bettered:

Just as a man sitting in the countryside employs, to accompany his meditation, a tree or a rock on which to anchor his eye, so a work by Camille Claudel in the middle of a room is, by its mere form, like those curious stones the Chinese collect: a kind of monument to inner thought, the tuft of a theme accessible to any and every dream. While a book, for example, must be taken from the shelves of a library, or a piece of music must be performed, the worked metal or stone here releases its own incantation, and our chamber is imbued with it.