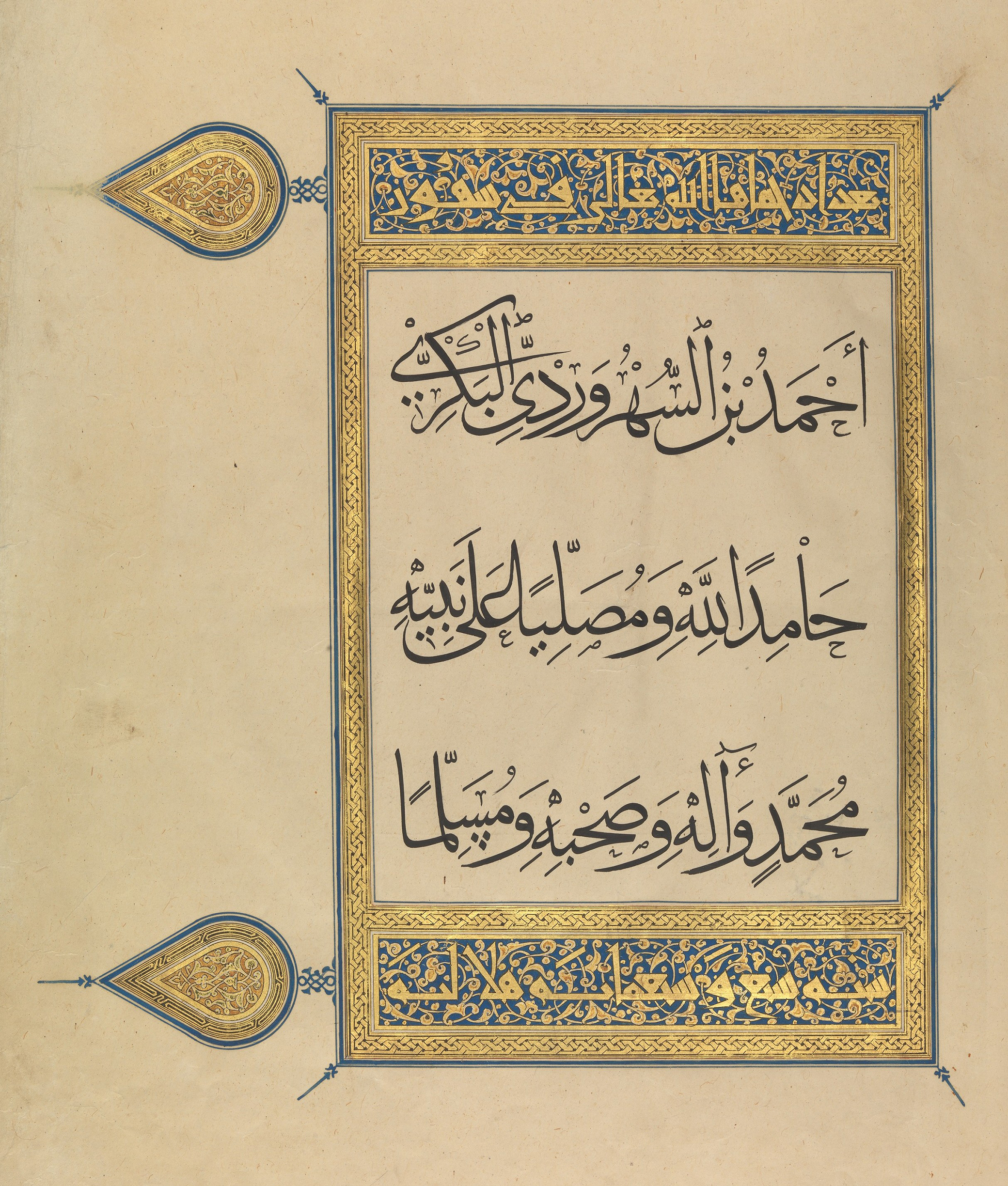

Folio from the Anonymous Baghdad Quran, with calligraphy by Ahmad ibn al-Suhrawardi al-Bakri and illumination by Muhammad ibn Aibak ibn ’Abdallah, c. 1307. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1955.

By comparison with Mecca and Damascus, ancient settlements whose origins blur into the furthest recesses of antiquity and legend, Baghdad was an upstart arriviste. It was founded on the Tigris River in 762 by the caliph Al Mansur (The Victorious), brother of the blood-shedding Al Saffa, who died of smallpox in 754. While Saffa’s greatest legacy was the Abbasid dynasty, his brother and successor’s gift to history was the even longer-lasting city which briefly bore his name: Medinat al Mansur. Its residents, however, preferred Medinat al Salam, the City of Peace, or Dar as Salam, the House of Peace, a reference to the description of paradise in the Quran. The name Baghdad, by which the city came to be known, is probably ancient Persian in origin, derived from the elision of bagh, “God,” and dadh, meaning “founded” or “foundation”—thus Baghdad was the city “founded by God,” the capital of the Islamic Empire, by now an immense dominion of five million square miles stretching from Morocco and the Iberian Peninsula to Central Asia.

The absolute zenith of this period can be narrowed down to the eight decades from 762 to 833, when the city, its people, and its culture reigned supreme during the caliphates of Mansur, Mahdi (ruled 775-85), Hadi (ruled 785–86), Harun al Rashid (ruled 786–809), Amin (ruled 809–13), and Mamun (ruled 813–33). It was a sign of the caliphate’s restlessly outward-looking ambition that Amin was the only caliph who died in Baghdad during those eight decades.

Of those half dozen names, one stands out above all others, and it is not the founder of the city but his grandson Harun al Rashid, “the Rightly Guided.” “So great were the splendors and riches of his reign, such was its prosperity, that this period has been called ‘the honeymoon,’ ” al-Masudi wrote in The Meadows of Gold. For Edward Gibbon he was “the most powerful and vigorous monarch of his race.”

One reason for Harun’s immense fame, in East and West alike, was his starring role in the perennially popular A Thousand and One Nights, a masterpiece of Indian, Persian, and Arab storytelling that dates back to the eighth and ninth centuries. He sashays through its stories charismatically, a nocturnal, street-prowling caliph, alternately enjoying himself in the arms of beautiful concubines, lopping off the heads of those who displease him, throwing bags of gold at those who amuse him, dashing off lines of poetry, and rolling with laughter at dirty jokes. In this collection of tall stories Harun, or at least a bawdy stereotype of the caliph, carries all before him.

Behind and beyond Harun’s extravagance, however exaggerated, there was real mettle and purpose. For Baghdad, Harun’s caliphate was a transformative experience that built upon, often literally, the solid foundations established by his grandfather Mansur to develop the infant city into a fully fledged world metropolis. Might and magnificence combined in torrents of royal patronage and expenditure, the funds for which were regularly replenished during repeated expeditions against the Byzantines. Harun led his first jihad at the ripe old age of fourteen and treated Baghdad like a favorite concubine, lavishing ever more treasures on it after each new triumph against Byzantium. This was a kaleidoscope of bloodshed and conquest, pilgrimage and procreation, science and scholarship, palatial building in Baghdad and expenditure on an imperial, never-to-be-repeated scale. As a mid-century caliph supposedly boasted to the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople, “The least of my territories ruled by the least of my subjects provides a revenue larger than your whole dominion.”

One of Harun’s finest achievements was to champion a translation movement, in which scholars in Baghdad translated some of the great works of classical Greek, Hindu, and Persian scholarship into Arabic; revised and in many cases improved them; and then circulated the updated texts throughout the Islamic Empire and far beyond. Abbasid envoys returned from expeditions to Byzantium weighed down by manuscripts of seminal works by Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Hippocrates, Galen, and others. The royal library collections swelled to monumental proportions—tens of thousands of volumes—emulated by fabulously wealthy and socially ambitious private patrons, who were only too happy to fuel the translation boom. Abbasid culture was pluralist and adaptive, open to the best the outside world had to offer. The wisdom and knowledge of the ancients was transmitted from West to East, ensuring that it survived to pass back, centuries later, into Western civilization, an enormous intellectual service to which we still owe much to this day. When the first Arabic translation of Euclid was published, it was dedicated to Harun. Scholar Philip Hitti likened this period in Baghdad to the Renaissance of the sixteenth century, noting that nothing comparable happened in the Arabic-speaking world for another thousand years: “It made of the Arab capital a world scientific center comparable to that of Rome in law, Athens in philosophy, and Jerusalem in religion.”

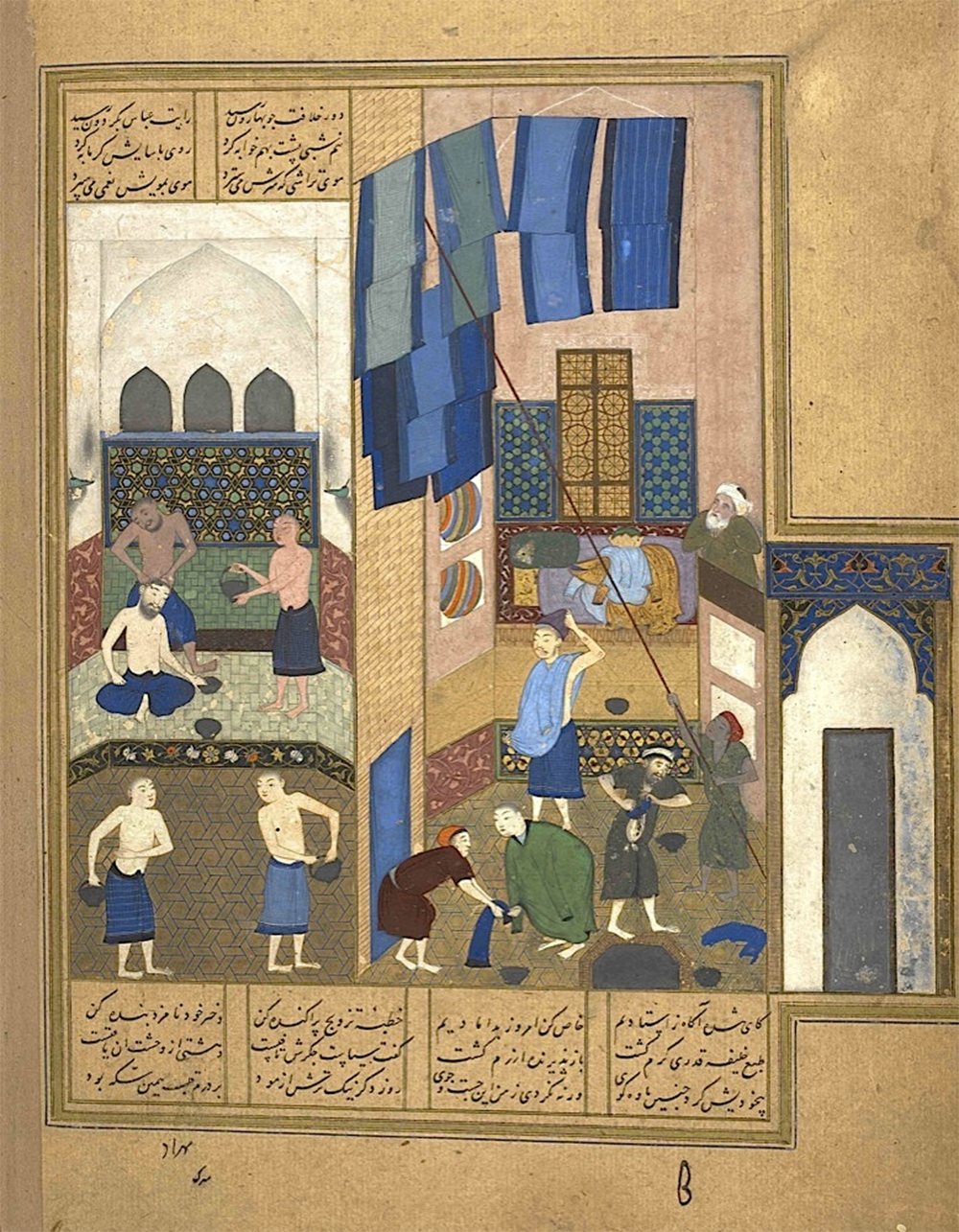

Harun personified this energizing atmosphere of intellectual curiosity and acquisition and set the tone for the city and its leading denizens. His salons included an eclectic circle of religious lawyers (Malik ibn Anas and Al Shafi), judges and historians (Al Waqidi and Ibn Qutayba), poets (Abu al-ʿAtahiya and the scandalous Abu Nuwas), musicians (Abu Ishaq al Mosuli), grammarians (Ali ibn Hamza), and humanists (Asmai and Abu Obayda)—though they had to be careful what they said. For conservative clerics with closed minds, the freewheeling philosophical, religious, and scientific discussions and debates Harun encouraged were anathema—as were the drinking bouts, lavish feasts, orgies, and homosexual liaisons. Harun and his cronies enjoyed drinking bouts that raged until dawn, fortified by the ruby-red wine of Shiraz, served in golden, silver, or crystal goblets, entertained by young women of the harem, who sang, strummed the lute, and aroused their drunken audience with the playful scarf dance and the languorous dance of the sabers. As the poet Muslim ibn Walid wrote in verses that encapsulated the spirit of the royal court, “What is this life but loving, and surrender to the / drunkenness of wine and pretty eyes?”

Little wonder, then, that behind his back the po-faced clerics should call Harun the Commander of the Unfaithful, a play on the caliph’s traditional moniker Amir al Muminin, or Commander of the Faithful. Yet this seems a little unfair in light both of Harun’s distinguished record of jihad against the infidels and his qualification as a hafiz, someone who could recite the entire Quran by heart, the only caliph apart from Uthman who was said to be able to do so.

The Islamic Empire to date had been a distinctly patriarchal place. Women were mothers, wives, and concubines but not public figures. Their proper place was considered to be the private, domestic sphere, as it remains today in much of the Muslim world. In Harun’s Baghdad, however, a small number of women from a very select background emerged into more public roles, either in the flesh or in the sources, which metaphorically lifted the veil on an otherwise secret realm.

At the very pinnacle of Baghdad society with Harun was his wife and cousin Zubayda. Even without her royal marriage to the most powerful man alive, she was a formidable character. As granddaughter of Mansur, Zubayda was of royal blood, immensely wealthy and well-educated in religion, poetry, and literature. She won lasting fame on two counts: first for her unrivaled displays of luxury, second for her charitable and religious activities. Harun’s Baghdad was a temple of conspicuous consumption, and no one was more conspicuous than Zubayda. It was said that during the most important court ceremonies she was so laden with gold and precious stones that two servants were required simply to help her stand upright. At her wedding to Harun in 781 she was given “precious stones, jewelry, diadems, and tiaras, silver and gold palanquins, scents, clothes, servants, and maids of honor,” together with a priceless waistcoat encrusted with rows of large rubies and pearls, booty seized from the Umayyads at the fall of Damascus in 750. Huge sums of money were distributed among the awestruck guests, gold dinars in silver bowls and silver dirhams in golden bowls, bags of musk and ambergris, expensive perfumes in glass bottles, and richly colored robes of honor woven with gold.

Those who might have been scandalized by such imperial ostentation would have looked more approvingly on Zubayda’s creation of a safe, nine-hundred-mile pilgrim route across the desert from Kufa, south of Baghdad, to the holy city of Mecca. Darb Zubayda, Zubayda’s Way, as it came to be known, was a large-scale engineering project, with wells, reservoirs, cisterns, state-of-the-art dams with filtering tanks, and fifty-four major resting stations built approximately every sixteen miles, a day’s march. When weary pilgrims finally arrived in Mecca, they were able to take advantage of the city’s first canal, commissioned by Zubayda, to supply spring water to the shrine. Thirteen hundred years later, the mountain source is still known as Ain Zubayda, Zubayda’s Well. The cost of this enormous scheme ran into millions of dinars, paid for from her own pocket. Millions of Muslim pilgrims have her to thank for it.

Other women in Baghdad enjoyed fame for their beauty—and price tags that reflected the giddy spirit of the age. There was a market for everything in the capital of the Islamic world, and that included the most desirable women. One of the most remarkable characters from the harem was surely Arib, nicknamed the “nightingale of the court” for the sweetness of her voice and the thousands of songs and poems she composed. Originally purchased by Amin, she later joined Mamun’s household, where she fearlessly cuckolded him in his own palace, spiriting in her lover for late-night trysts in an exceptionally dangerous adventure. Arib was said to have her hair massaged with rich pomades of amber and musk, later sold for a handsome price by her servants. As an old woman she was visited by two young men who asked her whether she was still interested in sex. “Ah, my sons, the lust is present but the limbs are helpless,” she replied. She died in Samarra in her nineties, having enthralled a succession of caliphs.

Excerpt adapted from Islamic Empires: The Cities That Shaped Civilization: From Mecca to Dubai by Justin Marozzi, published by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2019 by Justin Marozzi. Used by permission. All rights reserved.