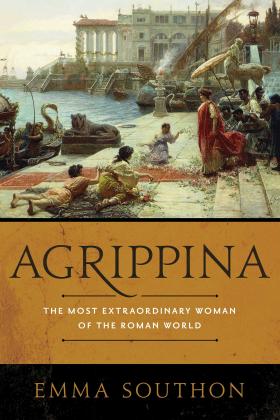

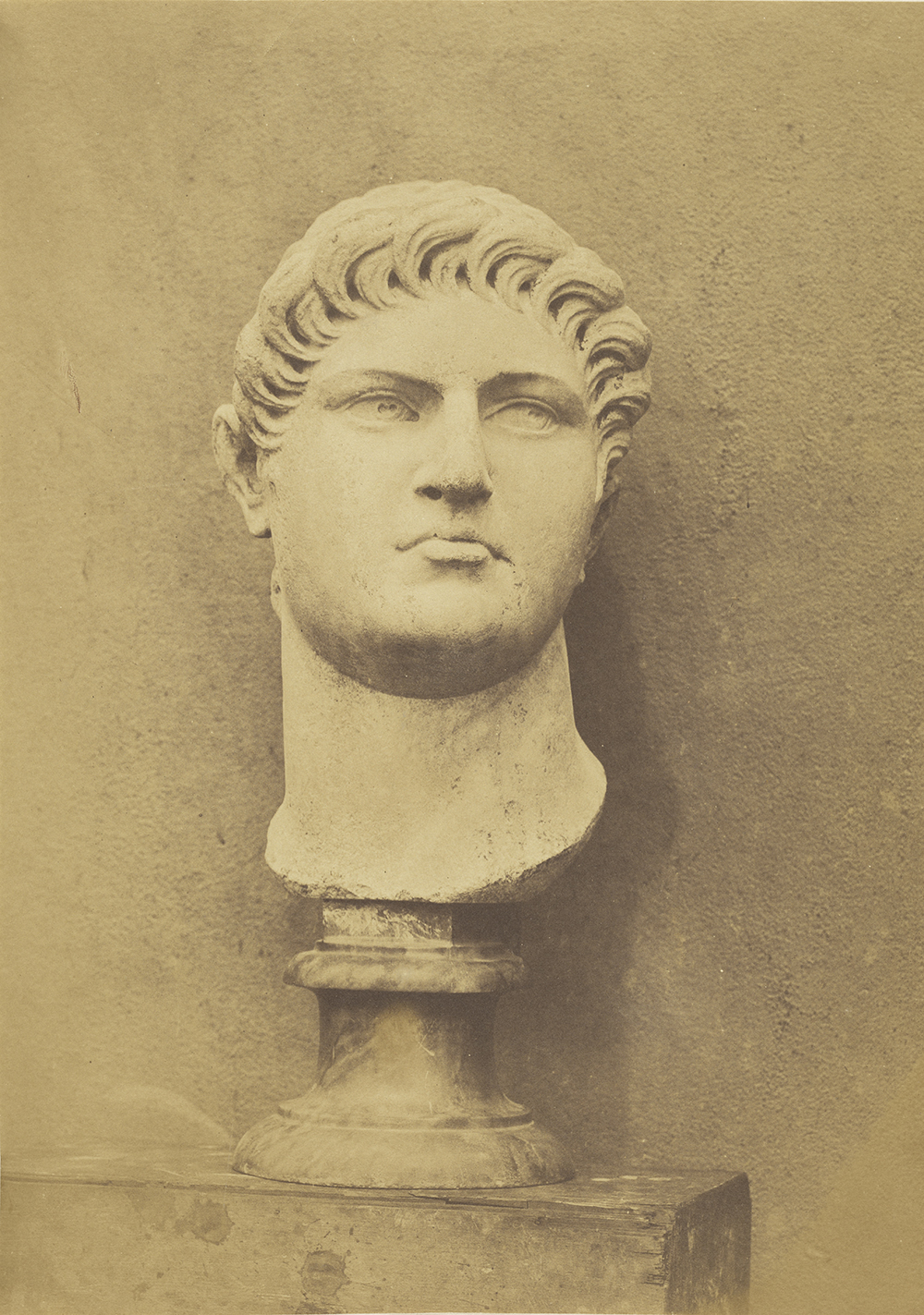

Portrait head of Agrippina the Younger, c. 50. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Being empress of the Roman world was not all sitting on thrones and riding in litters. It was only really 25 percent that. The rest of the time it was hard graft. The emperor (and empress) was not merely a ceremonial position, like being Queen Victoria, Empress of India. It was a proper full-time job that involved an awful lot of admin, listening to people droning on about things and reading and dictating letters. We have some insight into the workings of the job from Pliny the Younger’s ten volumes of letters, of which one entire book is just letters to his emperor Trajan, sent while Pliny was proconsul of Bithynia (Turkey). The letters are unbearable. They’re boring and sycophantic. As undergraduates, my friend Helen and I used to refer to them as the P.S. (Trajan) I Love You letters. Admittedly, Pliny was sent to deal with a troubled province, but the level of detail in his questions shows just how involved in the day-to-day lives of people across the empire the emperor could be. They’re all about tedious stuff like whether the local people should be allowed to start a fire brigade (nope), whether he should cover a smelly sewer (yes), about debts, whether he should kill Christians (yep) and Christian apostates (nope), whether his wife is allowed to use an imperial courier (yep), and on and on and on. There was almost nothing Trajan didn’t know about the goings-on in Bithynia and Trajan spent his entire reign conquering people. Claudius spent a week just about conquering the British and spent the rest of his thirteen-year reign answering letters. The amount of information flooding in daily from officials and armies and individuals across the empire was enormous. And it was the emperor’s job to deal with all of it. No wonder he let Agrippina get involved; she probably broke up the tedium.

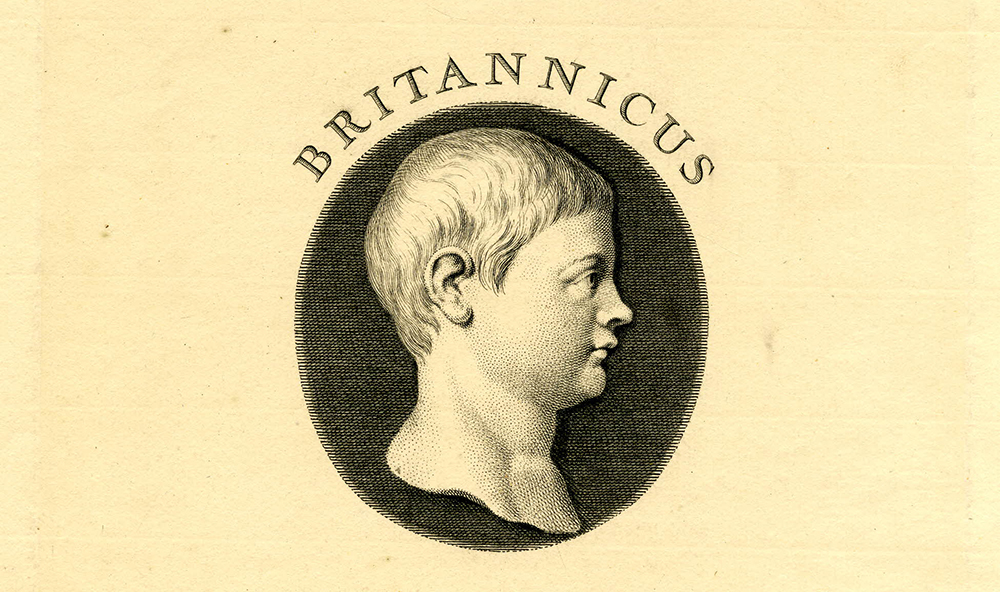

The primary narrative of Tacitus, and therefore pretty much every modern historian, is that Agrippina was single-mindedly focused on making sure that Nero—her son with her first husband, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus—would succeed her Claudius for the entirety of her time as Claudius’ wife. In Tacitus and Dio’s version of events, Narcissus, a freedman and adviser to Claudius, was a big fan of Claudius’ biological son, Britannicus, and wanted him to be emperor. As a result, the historians construct a feud between Narcissus and Agrippina that makes Agrippina nothing more than a power-grabbing whore using her own child for personal gain while destroying an innocent little boy and his rights. Narcissus doesn’t exactly come off as heroic, because he’s a Greek freedman and is therefore about equal to a woman in terms of being disgusting in the eyes of a Roman senator, but he is seen to be on the side of immutable Rightness. He was defending Britannicus’ natural right to be emperor and was the only one to recognize Agrippina’s extremely nefarious plan to sideline poor innocent Britannicus and replace him with Nero.

Such a narrative is obviously ridiculous. For one thing, Narcissus personally gave the order to murder Britannicus’ mother, Messalina. If there was anyone Britannicus probably didn’t want on his team, it was Narcissus. If there was one person who was going to accidentally brutally cut his own throat while combing his hair when Britannicus became supreme ruler of the Western world, it was Narcissus. The idea that Britannicus, a boy who was eight when Agrippina married his dad and nine when Nero was adopted by Claudius, was a viable proposition for ruling anything at all is laughable. The idea that Narcissus would start fighting for the rights of a nine-year-old out of the goodness of his heart and strong desire for biological justice is even funnier. Finally, from the day Nero got his toga virile it was painfully obvious that Nero was a man and a citizen while Britannicus was a boy. Nero was dressed in the plain toga of an adult while Britannicus was dressed in a tunic or striped toga, with his massive bulla. A lot tends to get made of this distinction, as if the fact that Nero was a teenager and was presumably going through puberty and growth spurts while Britannicus was still a small child wasn’t a factor. But still, in terms of optics, it was fairly effective. But, fairly effective is never enough when it comes to the highly difficult subject of succession, so Nero was also made the consul designate, which meant he got to wear consular robes. So this wasn’t just a thirteen-year-old standing next to a nine-year-old, or a man standing next to a child, it was a magistrate standing next to a child. A nine-year-old standing next to the vice president. Just in case that still wasn’t enough, they threw Nero some games and rode the imperial family past the crowds for them to cheer, as was traditional. Britannicus went past in the Roman version of school shorts, but Nero was dressed as if he were receiving a military triumph. Tacitus says that the aim was to “let the people see the one in the insignia of imperial command, the other in his puerile garb, and anticipate the destinies of each” because he’s very good on optics. And the point is undeniable: Nero was very obviously being displayed as Claudius’ successor.

Claudius’ illness in 53 is well covered in the sources, though, or at least as well covered as such things get in that we know that Claudius was ill and that the illness lasted long enough that Nero and Agrippina were able to put on some games for Claudius’ health. Suetonius says that the games included beast-baiting, and Dio says they included races, so take your pick. Either way they took some organization and were a nice way for Nero and Agrippina to appear in public without Claudius attached. Dio claims that by this time Agrippina was regularly appearing in public, sitting on a separate but equal dais next to Claudius, receiving ambassadors or visitors or transacting the tedious daily business of the empire, so she would be used to being treated as his equal in public but only by his side. This was a chance for Agrippina to be on display without her husband and oversee some games in her own right. More importantly, it was a reminder that the empire endured and everything continued as normal when Claudius was not around.

At about the same time in 53, the final touch to Nero’s position as successor was completed and he was officially married to Claudius’ biological daughter, his adoptive sister Octavia, as she was finally old enough to legally marry. You may remember that Octavia’s first fiancé had been accused of incest with his sister and removed from the engagement before killing himself on Claudius and Agrippina’s wedding day and so she had been formally betrothed to Nero a couple of years back. There had been one minor hurdle to overcome before the marriage could happen: in Roman law, marrying an adoptive sibling was considered to be incest. However, marrying a close blood relative hadn’t been a problem for Claudius and Agrippina so there’s no way they were letting something as ridiculous as the law stand in the way of this brilliant plan either. At the same time, though, their definitely incestuous marriage had raised more eyebrows than were ideal, so they needed to deal with the situation carefully. Their solution was to have Octavia adopted out of the family so she was no longer technically Claudius’ daughter and then immediately marry her back in, which was complicated and time-consuming and an utter farce of a situation but worked. Two years after the engagement was announced, Nero was now Claudius’ son, his son-in-law, the Prince of Youths, the consul designate, and able to act as a magistrate; he held imperium (military power) both inside and outside the walls of Rome, and got to march about in consular robes all the time and in triumphal robes on special occasions. The deed was done. According to Dio, the gods warned the Romans of the coming terrors. On their wedding night, he tells us, the sky appeared to burst into flames.

However, the pushy stage mum isn’t the only narrative that Agrippina gets during these years. She also gets a classic wicked stepmother story. The wicked stepmother is a tale as old as humans and it’s a favorite of the Romans. In this story, Agrippina is the wicked stepmother abusing poor Britannicus, who is our Cinderella: the adorable innocent, cruelly abused. There is no doubt that Britannicus was sidelined in the imperial family. As the youngest child, he was sort of the most useless, but he was also the most potentially dangerous as Messalina’s son and a rival for the throne. Thankfully he was tiny, so he couldn’t get involved in public life properly unless Claudius granted him his toga virilis at a preposterously young age. Although the idea of a nine-year-old senator is very funny and quite adorable, funny isn’t really what Claudius and Agrippina were ever going for.

Dio also says that Agrippina kept Britannicus under house arrest and prevented him from appearing in public or seeing his father. Tacitus goes even further and claims that Agrippina wouldn’t even let him have slaves. How was a prince supposed to live without slaves? Was he supposed to stroke his own back? These are more serious charges of cruelty and rather impossible to prove or disprove. The implications in these accusations are twofold: first, that allowing Claudius to see Britannicus would arouse Claudius’ natural paternal sympathies and he would realize how cruel he was being to the little boy by not making him the next emperor and Agrippina’s plans would be lost, and secondly that Agrippina had the power in the imperial household to prevent the emperor and his son from seeing one another. Claudius is a nonentity in this story; it’s not about him. You can decide for yourself what he was supposed to be doing while his only biological son was kept away from him for three years: Weeping into his cups over his beloved son? Idly trying to remember if he ever had a son? Completely oblivious? It’s impossible to know. Of course, it doesn’t really matter whether this actually happened or not, or even whether it is plausible; what matters is that the story emphasizes the fact that Agrippina was a wicked stepmother taking away Britannicus’ natural right to inherit the throne, which aims to make the reader feel pity for little Britannicus. The pity makes Agrippina seem all the more villainous, like all wicked stepmothers should be. And Agrippina is absolutely being forced into that trope.

She is molded so hard into the wicked stepmother role that it’s quite easy to forget that she had two stepdaughters, too, Antonia and Octavia. Antonia was twenty when Nero was adopted and she was married to her second husband, Faustus Cornelius Sulla Felix, so she was probably out of the household and spent her time being a good Roman wife. She certainly didn’t do anything that a good Roman wife wouldn’t do or else we’d know about it. Octavia was younger, just ten or so when Nero was adopted, and being raised in the imperial palace. She was fourteen when she married the sixteen-year-old Nero, and he hated her as much as she hated him. Eventually, he murdered her. Because she was empress for a little while as Nero’s wife and was, like her namesake, seen as such a deeply tragic, ideal woman, she was the subject of a tragedy written by an anonymous playwright that tells the story of her sad life. Agrippina is in it as a ghost, which is quite fun.

The story focuses entirely on the cruel persecution of Britannicus and then Octavia’s terrible treatment at the hands of Nero. Agrippina appears to talk about Nero and his second wife Poppea but not Octavia. The relationship between Agrippina and her stepdaughter, who then became her daughter-in-law, is completely obscure. Stepdaughters are no threat to the stepmother so they just don’t matter. Stepdaughters are also entirely irrelevant to the wider story that Tacitus and Dio are telling, which is that Agrippina’s power marked a period of extreme dysfunction for the Roman state. She is little more than a symbol of every possible kind of disorder and destruction.

Excerpted from Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Roman World by Emma Southon. Copyright © 2019 by Emma Southon. Published by Pegasus Books. Reprinted by permission.