Bookcase with a secretary, by anonymous, after Michael Angelo Nicholson, 1827. Rijksmuseum.

Encyclopædia Britannica occupies a special place in the annals of publishing and the history of the West. Although its full influence, like that of any great work of literature, is ultimately immeasurable in concrete terms (the number of units sold is never the best barometer), its larger social and cultural impact—as a reference work, a spark to learning, a symbol of aspiration, a recorder of evolving knowledge, and a mirror of our changing times—has been extraordinary.

The Whole-Set Club

Reading an entire Britannica print set has been a goal of bibliophiles and self-learners for centuries, and some of the hearty souls who have accomplished this feat are detailed here.

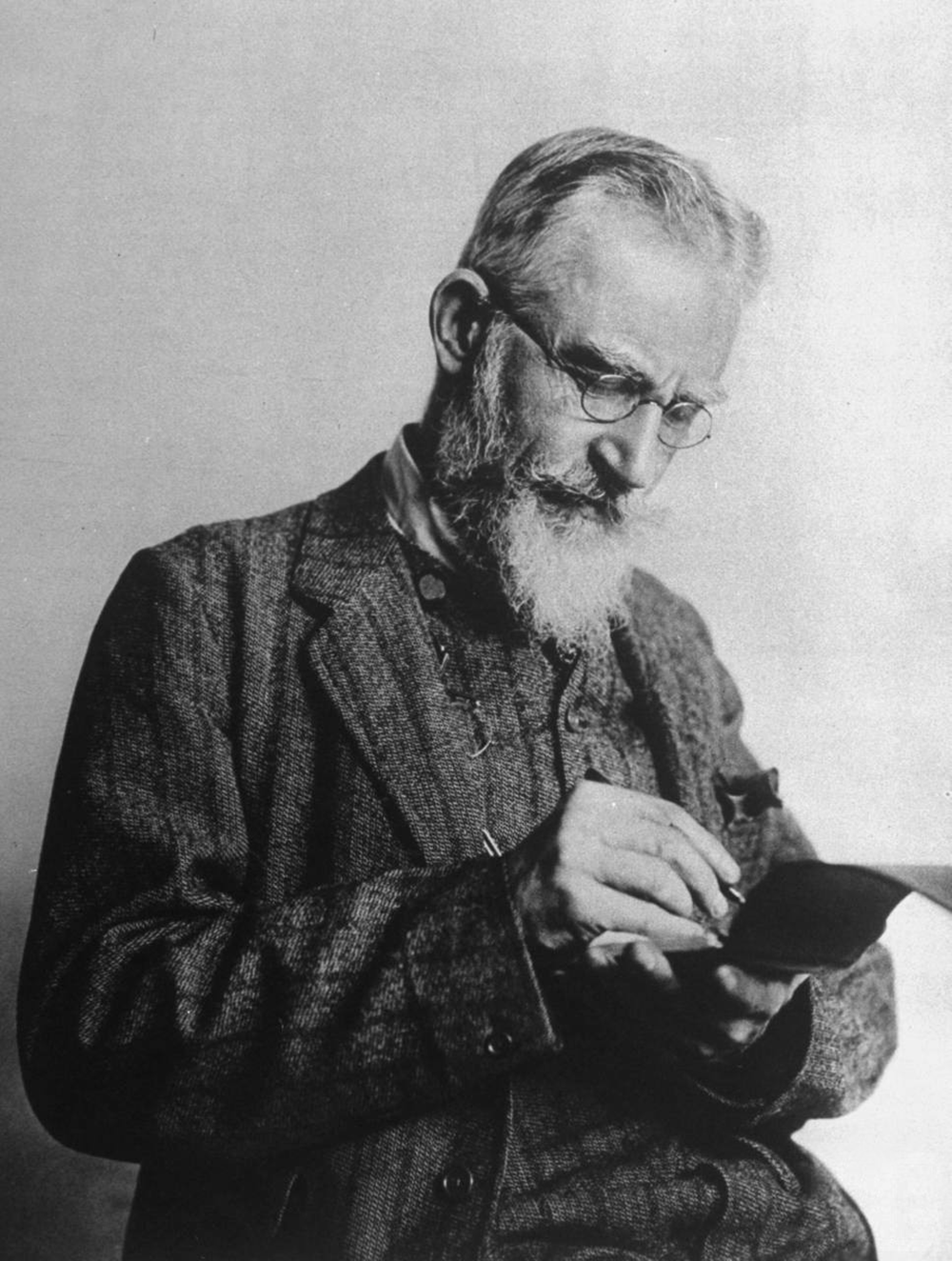

George Bernard Shaw, recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925, was particularly fond of Britannica’s twenty-four-volume ninth edition (1875–89). He claimed to have read the entire set during visits to the British Museum, skipping only Britannica’s lengthy science articles.

C.S. Forester (1899–1966) is best known for his popular Horatio Hornblower seafaring novels (1937–67) and for his 1935 story The African Queen, the classic 1951 film version of which was directed by John Huston and starred Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn. But he also enjoys a special seat in the “whole-set club,” one not many readers have ever occupied: he read his set of Britannica three times! This may seem like an impossible feat, but Forester was one of those rare birds with a photographic memory who could read four thousand words per minute. “He read the Encyclopædia Britannica for bedside reading,” remembered his son.

George Forman Goodyear was a prominent man of many talents in Buffalo, New York, whose obituary in 2002 listed “lawyer, chemist, Buffalo television pioneer, school board president, mayoral candidate, cultural leader, and philanthropist.” The article also noted his insatiable thirst for knowledge, which led him to read the entire twenty-four-volume set of Britannica’s fourteenth edition (1929–73). He began reading his set while a student at Harvard Law School in 1929 and continued reading at a pace of a thousand pages a year, finally finishing his feat twenty-two years later.

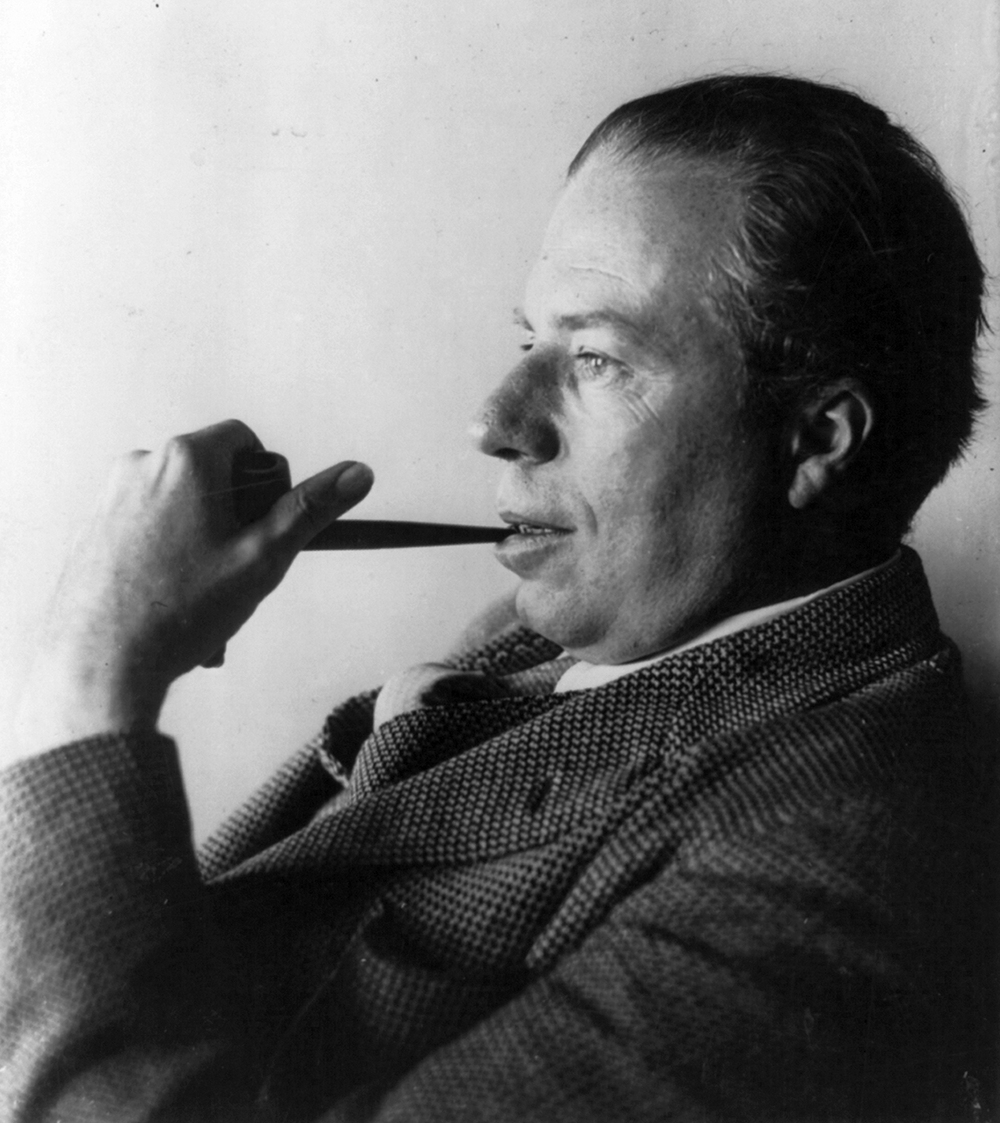

Alan Watts was called by the New York Times “perhaps the foremost Western interpreter of Eastern thought for the modern world.” The British-born writer and philosopher could not claim membership in the “whole-set club,” but his good friend Aldous Huxley could. As Watts recalled in his autobiography In My Own Way (1972), Huxley “had read the entire Encyclopædia, but at random. He would, for example, look up the article on the letter P, then go off to a party at which he would gently move the conversation to this subject and then give an extremely learned, and invariably witty, discourse on the history of this letter.”

Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, to the best of our knowledge, is also not a member of this distinguished club, but he does deserve special mention for his unique encounter with a “whole set” one fateful day in 1998. While he reached for a book on anatomy by Leonardo da Vinci, his home bookshelf collapsed, sending the 129-pound set of Britannica volumes cascading down upon him. He was left with three broken ribs, and the Stones had to postpone the opening of their European tour. But Richards took the mishap in stride. “All part of life’s rich pageant,” he laughed.

A Writer’s Eldorado

Given the ubiquity of Britannica in Western culture, it is hardly surprising that the publication has been popular with novelists and poets throughout the centuries and made frequent appearances in their work.

Salman Rushdie, for example, in The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995), had a character describe a dream of “peeling off my skin plantain-fashion, of going forth naked into the world, like an anatomy illustration from Encyclopædia Britannica, all ganglions, ligaments, nervous pathways and veins, set free from the otherwise inescapable jails of color, race and clan.”

For Edgar Allan Poe, Encyclopædia Britannica was a handy source for explaining geographical and scientific phenomena, as seen in this passage from “A Descent into the Maelström,” an 1841 short story about a man who survives a shipwreck and a whirlpool:

In regard to the depth of the water, I could not see how this could have been ascertained at all in the immediate vicinity of the vortex…The idea generally received is that this, as well as three smaller vortices among the Feroe islands, “have no other cause than the collision of waves rising and falling, at flux and reflux, against a ridge of rocks and shelves, which confines the water so that it precipitates itself like a cataract; and thus the higher the flood rises, the deeper must the fall be, and the natural result of all is a whirlpool or vortex, the prodigious suction of which is sufficiently known by lesser experiments.”—These are the words of the Encyclopædia Britannica.

For novelist James Michener, Britannica was a daily companion. He consulted the encyclopedia so often that he kept it, in his words, “right at my elbow in a specially built bookcase which I myself fabricated so that I could have all the volumes in one line.” In fact, he reportedly traveled with a set of Britannica in his car.

For the ever-versatile Christopher Morley, Britannica meant an opportunity for some doggerel called “Epitaph on the Proofreader of the Encyclopædia Britannica”:

Majestic tomes, you are the tomb

Of Aristides Edward Bloom,

Who labored, from the world aloof,

In reading every page of proof.

From A to And, from Aus to Bis

Enthusiasm still was his;

From Cal to Cha, from Cha to Con

His soft-lead pencil still went on.

But reaching volume Fra to Gib,

He knew at length that he was sib

To Satan; and he sold his soul

To reach the section Pay to Pol.

Then Pol to Ree, and Shu to Sub

He staggered on, and sought a pub.

And just completing Vet to Zym,

The motor hearse came round for him.

He perished, obstinately brave:

They laid the Index on his grave.

For T.S. Eliot, on the other hand, the pachyderm of print sets elicited not awe but a sigh, a lament, a remembrance of things lost. As he suggested in “Animula” (1929), Britannica’s massive tomes sat hauntingly on the bookshelf, reminding him of the countless facts, proscriptions, and adult concerns that gather over years and smother the unfettered life we enjoyed as a child:

The heavy burden of the growing soul

Perplexes and offends more, day by day;

Week by week, offends and perplexes more

With the imperatives of “is and seems”

And may and may not, desire and control.

The pain of living and the drug of dreams

Curl up the small soul in the window seat

Behind the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Writers in languages other than English have also poignantly felt the impact of Britannica. “If I were asked to name the chief event in my life,” wrote Jorge Luis Borges, “I should say my father’s library. In fact, I sometimes think I have never strayed outside that library. I can still picture it…I vividly remember so many of the steel engravings in Chambers’s Encyclopædia and in the Britannica.” Britannica was so special to Borges that after winning a literary award and a “lordly sum” of prize money for a collection of his essays in 1929, the young writer in Buenos Aires used part of his precious winnings to purchase a used set of Britannica’s famed eleventh edition.

Killers, Crimes, and Britannica

Britannica has had an interesting connection with crime and criminals over the years, as briefly evidenced below. Al Capone—a.k.a. Scarface, Public Enemy No. 1—headed off to prison in May 1932. Convicted of income-tax evasion, the Chicago mobster had been sentenced to eleven years, then the stiffest penalty ever given for tax fraud. He was shipped to the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia, an institution noted as one of the country’s toughest prisons. “He might as well make up his mind that he is a marked man among the army of forgotten men who inhabit the institution,” wrote the Atlanta Constitution. “He will undergo inconveniences. He will obey orders instead of issuing them.” The newspaper could not have been more wrong. Little time passed before Capone was wielding his influence just as mightily behind bars, buying a wide variety of favors and supplies. His cell was filled with cigars, a rug, a typewriter, and even…the twenty-four-volume set of Britannica’s fourteenth edition (1929–73). Such mockery of the system would not be tolerated for long, and two years later Capone was transferred to Alcatraz, the country’s new “escape-proof prison” in San Francisco Bay, where America would now house its most dangerous criminals.

For Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Britannica served as the perfect cover for the not-so-perfect crime. In “The Red-Headed League” (1891), Sherlock Holmes must ascertain why an organization would pay a handsome fee to a red-haired man for doing nothing more than copying pages out of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Eight weeks passed away like this,” said the copyist,

and I had written about Abbots and Archery and Armour and Architecture and Attica, and hoped with diligence that I might get on to the B’s before very long. It cost me something in foolscap and I had pretty nearly filled a shelf with my writings. And then suddenly the whole business came to an end.

To Doyle biographer Charles Higham (The Adventures of Conan Doyle: The Life of the Creator of Sherlock Holmes, 1976), this use of the encyclopedia is notable for two reasons. It not only shows a touch of humor in the Sherlock Holmes’ tales but also serves as a sociological mirror of the times, confirming “the view of the upper middle class that the working orders were simply dolts.”

For mystery writer Ruth Rendell, in Piranha to Scurfy and Other Stories (2000), Encyclopædia Britannica was not the perfect cover for a crime as it was for Doyle but perfect for executing the crime itself—murder, in fact.

His hands moved across the table to rest on Piranha to Scurfy [the catch titles on the spine of a volume of Britannica]; he lifted it in both hands and brought it down as hard as he could on her head. Once, twice, again and again. The first time she screamed, but not again after that. She staggered and sank to her knees and he beat her to the ground with volume eight of the Encyclopædia Britannica. She was an old woman: she put up no struggle; she died quickly. He very much wanted not to get blood on the book—she taught him books were sacred—but there was no blood. What was shed was shed inside her.

Excerpted from the afterword to the Encyclopædia Britannica Anniversary Edition: 250 Years of Excellence (1768–2018). Copyright © 2018 by Encyclopaedia Britannica. Reprinted with permission.