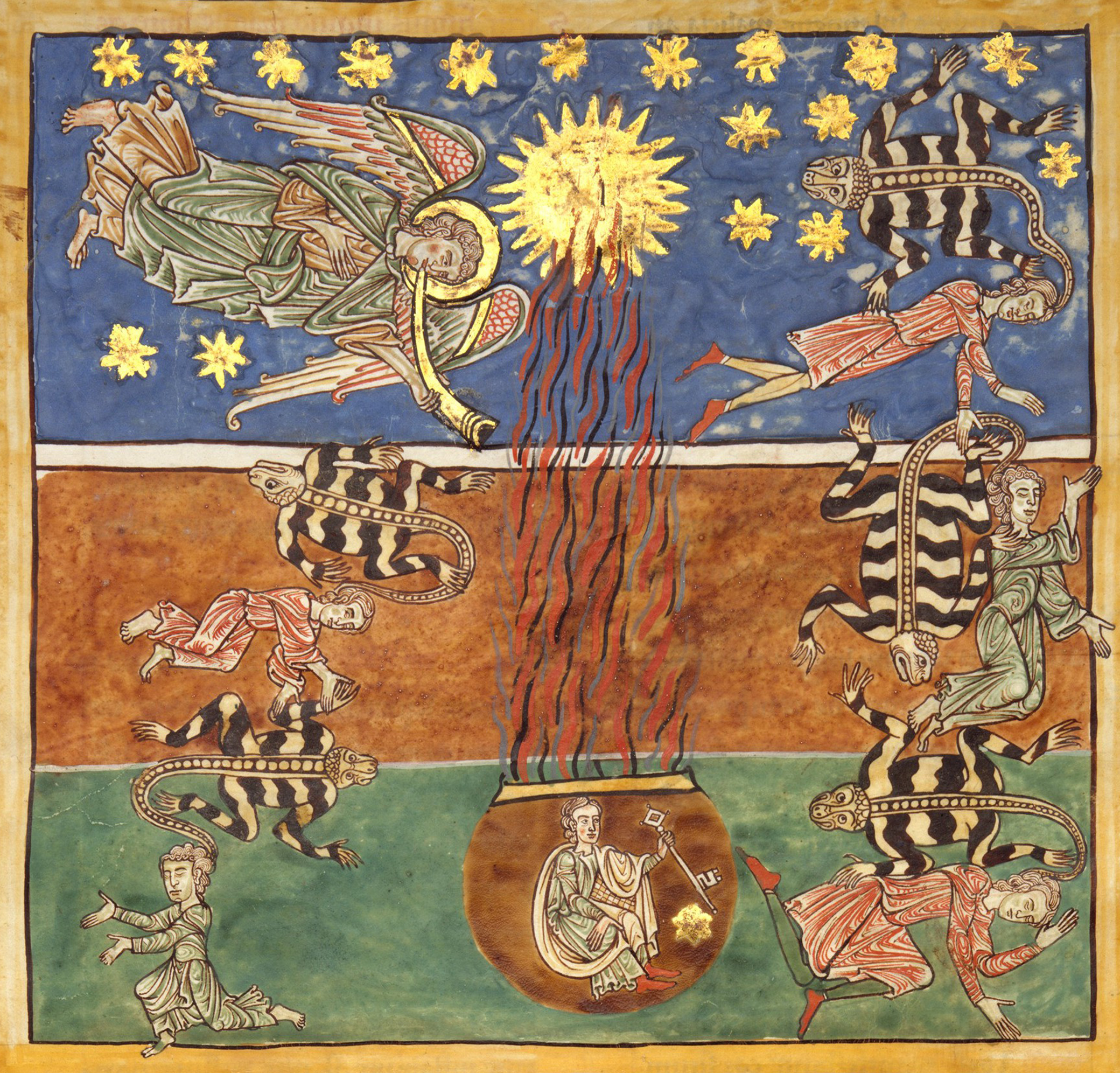

Leaf from a Beatus Manuscript: At the Clarion of the Fifth Angel’s Trumpet, a Star Falls from the Sky; the Bottomless Pit Is Opened with a Key; Emerging from the Smoke, Locusts Come Upon the Earth and Torment the Deathless, c. 1180. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, The Cloisters Collection, Rogers and Harris Brisbane Dick Funds, and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1991.

You lied to us. You gave us false hope. You told us that the future was something to look forward to. And the saddest thing is that most children are not even aware of the fate that awaits us. We will not understand it until it’s too late. And yet we are the lucky ones. Those who will be affected the hardest are already suffering the consequences.

—Greta Thunberg, 2019

Climate activist Greta Thunberg, whose speech to Parliament from this year is featured in our Fall 2019 issue, Climate, is leading one of many climate protests across the world this Friday, the first day of the Global Climate Strike. In this selection of readings from our new issue—and from issues going back to our second, Book of Nature—people saw there was something wrong with the weather, the environment, or the climate and tried to do something about it, even if that meant only saying that the world wasn’t quite right.

2019 | London

Katharine Viner updates the Guardian style guide:

Use climate emergency, crisis, or breakdown instead of climate change.

Use global heating instead of global warming.

Use wildlife instead of biodiversity (when appropriate).

Use fish populations instead of fish stocks.

Use climate-science denier or climate denier instead of climate skeptic.

The earth is our existence, and our body is attached to the earth.

—Daulat Qazi, c. 1650

1848 | Cooperstown, NY

Susan Fenimore Cooper speaks for the trees:

Just at the point where the village street becomes a road and turns to climb the hillside, there stands a group of pines, a remnant of the old forest. There are many trees like these among the woods, far and near such may be seen rising from the hills, now tossing their arms in the stormy winds, now drawn in still and dark relief against the glowing evening sky. Their gaunt, upright forms standing about the hilltops, and the ragged gray stumps of those which have fallen, dotting the smooth fields, make up the sterner touches in a scene whose general aspect is smiling. But although these old trees are common upon the wooded heights, yet the group on the skirts of the village stands alone among the fields of the valley; their nearer brethren have all been swept away, and these are left in isolated company, differing in character from all about them, a monument of the past.

c. 1925 | Sacramento Valley

Kate Luckie foretells the apocalypse:

People talk a lot about the world ending, but this world will stay as long as Indians live. When the Indians all die, then God will let the water come down from the north. Everyone will drown. That is because the white people never cared for land or deer or bear. When we Indians kill meat, we eat it all up. When we dig roots, we make little holes. When we build houses, we make little holes. When we burn grass for grasshoppers, we don’t ruin things. We shake down acorns and pine nuts. We don’t chop down the trees. We only use dead wood. But the white people plow up the ground, pull up the trees, kill everything. The tree says, “Don’t. I am sore. Don’t hurt me.” But they chop it down and cut it up. The spirit of the land hates them. They blast out trees and stir it up to its depths. They saw up the trees. That hurts them. The Indians never hurt anything, but the white people destroy all.

1847 | Rutland, VT

George Perkins Marsh on climate change as self-interest.

I desire to draw your special attention to the introduction of a better economy in the management of our forestlands. The increasing value of timber and fuel ought to teach us that trees are no longer what they were in our fathers’ time, an encumbrance. We have undoubtedly already a larger proportion of cleared land in Vermont than would be required, with proper culture, for the support of a much greater population than we now possess, and every additional acre both lessens our means for thorough husbandry by disproportionately extending its area and deprives succeeding generations of what, though comparatively worthless to us, would be of great value to them. The inconveniences resulting from a want of foresight in the economy of the forest are already severely felt in many parts of New England and even in some of the older towns in Vermont. Steep hillsides and rocky ledges are well suited to the permanent growth of wood, but when in the rage for improvement they are improvidently stripped of this protection, the action of sun and wind and rain soon deprives them of their thin coating of vegetable mold, and this, when exhausted, cannot be restored by ordinary husbandry. They remain therefore barren and unsightly blots, producing neither grain nor grass, and yielding no crop but a harvest of noxious weeds to infest with their scattered seeds the richer arable grounds below. But this is by no means the only evil resulting from the injudicious destruction of the woods. The vernal and autumnal rains, and the melting snows of winter, no longer intercepted and absorbed by the leaves or the open soil of the woods, but falling everywhere upon a comparatively hard and even surface, flow swiftly over the smooth ground, washing away the vegetable mold as they seek their natural outlets, fill every ravine with a torrent, and convert every river into an ocean. The suddenness and violence of our freshets increases in proportion as the soil is cleared; bridges are washed away, meadows swept of their crops and fences, and covered with barren sand, or themselves abraded by the fury of the current, and there is reason to fear that the valleys of many of our streams will soon be converted from smiling meadows into broad wastes of shingle and gravel and pebbles, deserts in summer, and seas in autumn and spring. The changes, which these causes have wrought in the physical geography of Vermont within a single generation are too striking to have escaped the attention of any observing person, and every middle-aged man who revisits his birthplace after a few years of absence looks upon another landscape than that which formed the theater of his youthful toils and pleasures.

1864 | Turin

And George Perkins Marsh on a disturbing agent.

Man is everywhere a disturbing agent. Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of nature are turned to discords. The proportions and accommodations which insured the stability of existing arrangements are overthrown. Indigenous vegetable and animal species are extirpated and supplanted by others of foreign origin, spontaneous production is forbidden or restricted, and the face of the earth is either laid bare or covered with a new and reluctant growth of vegetable forms and with alien tribes of animal life. These intentional changes and substitutions constitute, indeed, great revolutions, but vast as is their magnitude and importance, they are, as we shall see, insignificant in comparison with the contingent and unsought results which have flowed from them. The fact that, of all organic beings, man alone is to be regarded as essentially a destructive power, and that he wields energies to resist which nature—that nature whom all material life and all inorganic substance obey—is wholly impotent, tends to prove that, though living in physical nature, he is not of her, that he is of more exalted parentage and belongs to a higher order of existences than those which are born of her womb and live in blind submission to her dictates.

2011 | Washington, DC

The U.S. government on global warming.

Congress accepts the scientific finding of the Environmental Protection Agency that “the public health of current generations is endangered and that the threat to public health for both current and future generations will likely mount over time as greenhouse gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere and result in ever greater rates of climate change.

When nature is overriden, she takes her revenge.

—Marya Mannes, c. 1958

1964 | Washington, DC

Congress defines the wilderness.

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean in this Act an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions and which (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; (3) has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition; and (4) may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.

2100 | Rome

Mary Shelley’s future plague.

Have any of you, my readers, observed the ruins of an anthill immediately after its destruction? At first it appears entirely deserted of its former inhabitants; in a little time you see an ant struggling through the upturned mold; they reappear by twos and threes, running hither and thither in search of their lost companions. Such were we upon the earth, wondering aghast at the effects of pestilence. Our empty habitations remained, but the dwellers were gathered to the shades of the tomb. As the rules of order and pressure of laws were lost, some began with hesitation and wonder to transgress the accustomed uses of society. Palaces were deserted, and the poor man dared at length, unreproved, intrude into the splendid apartments, whose very furniture and decorations were an unknown world to him. It was found that, though at first the stop put to all circulation of property, had reduced those before supported by the factitious wants of society to sudden and hideous poverty, yet when the boundaries of private possession were thrown down, the products of human labor at present existing were more, far more, than the thinned generation could possibly consume. To some among the poor this was matter of exultation. We were all equal now; magnificent dwellings, luxurious carpets, and beds of down were afforded to all. Carriages and horses, gardens, pictures, statues, and princely libraries, there were enough of these even to superfluity; and there was nothing to prevent each from assuming possession of his share. We were all equal now; but near at hand was an equality still more leveling, a state where beauty and strength, and wisdom, would be as vain as riches and birth. The grave yawned beneath us all, and its prospect prevented any of us from enjoying the ease and plenty which in so awful a manner was presented to us.

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 300 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.