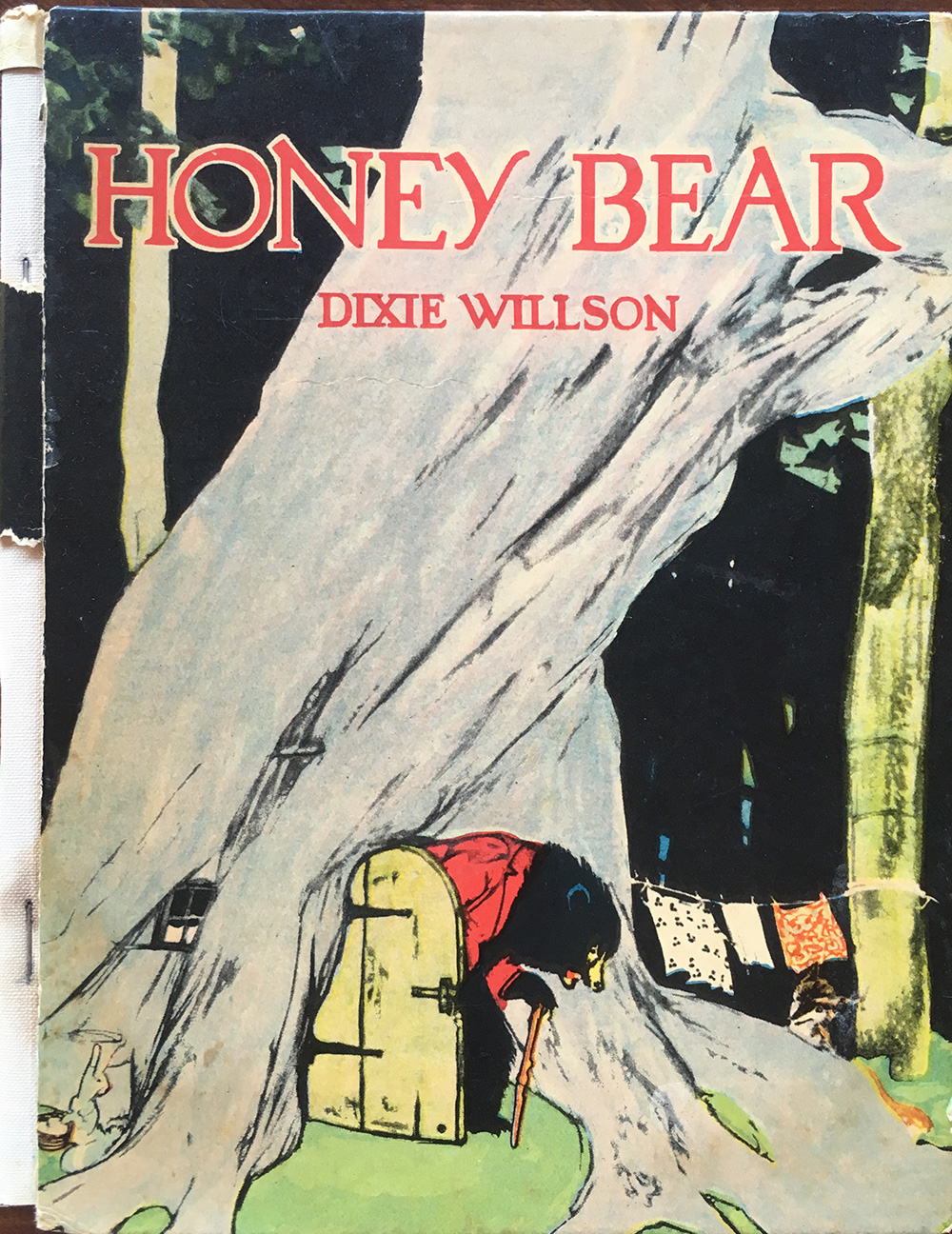

An image from the 1923 edition of Honey Bear. Courtesy of Willy Blackmore.

One children’s book I read to my four-year-old daughter always begins with a preamble, even if she doesn’t approve: a brief note from Alice Ann Blackmore, my grandmother, written in 1976 on the flyleaf of Dixie Willson’s Honey Bear. “It is a rare bit of sing-song for children,” my grandma wrote of the book, which had been published in 1923, when she was just three years old, “as rare as Aunt Dixie herself. Please be sure it stays in the family with whomever cares most about it.” That, I tell Story, my daughter, is her. We then proceed to read the tale of the “wildest thing of any in the dusky, rusky forest”—an old black bear—and the little baby he may or may not plan to eat.

The woman my grandmother called her aunt was a relative through friendship, not family. Born in 1890, Dixie Willson was the daughter of John David and Rosalie Willson, who ran in the same society circles in Mason City, Iowa, as my grandmother’s parents, Dwight Moore, president of a local bank, and his wife, Stella. Willson’s younger brother, the composer Meredith Willson, is best remembered today for writing The Music Man. But there was a time, particularly during in the 1920s and 1930s, when Dixie was the most famous scion of this Iowa town.

The children’s books she wrote were just a piece of a career that was as ambitious as it was unique, taking her from writing for both Hollywood and magazines like McClure’s and Good Housekeeping to working in the test kitchens at Betty Crocker and developing a toy for children. Her adventures—which also included being a chorus girl in the Ziegfeld Follies as well as being personally chosen by Howard Hughes to write his never-completed biography, Who’s Hughes?—were fodder both for her books and screenplays for films including An Affair of the Follies (1927) and God Gave Me 20 Cents (1926). Still, Honey Bear is the book Willson is best—if at all—remembered for. It’s a book that my great aunt Ellen Moore still remembers with delight today, and one I hope will leave a big impression on my own daughter.

But for the three young Moore sisters, Aunt Dixie was thrilling not because of who she knew or what she had done but because of the fantasy world she opened to them. “She used to tell us stories about a town in southern Iowa called Vinton”—Willson’s own Winesburg, Ohio—said Ellen Moore, who has survived her two sisters and remains sharp and inquisitive at ninety-one. “We would just love it when she came. She was so fun and lively, and she would have such a good time. I guess she was making up stories as she told them to us. But maybe not—maybe the stories already existed in her mind.”

My grandmother died in the winter of 2013. When we were clearing out her house the next spring, I found two invitations from Aunt Dixie asking Alice Ann to what Willson called a “kindergarten party.” The yellowed onionskins were collaged over with drawings of children that look as if they could have come from her own books, the typewritten words spilling around the images. They resemble tiny works of art, as if Hannah Höch were your babysitter. I was mildly curious about Willson when my Aunt Kathy gave me the family copy of Honey Bear after my daughter was born, but after I saw the invitations, I became fascinated:

I have a little friend named Floyd who is just as big as you are and who has some red shoes, and some day he is coming to see me and then we will both come and play with you if you think that would be nice. And when he comes maybe you can come too and will have a kindergarten party and my house and have chicken bones.

What kid wouldn’t want to go eat chicken bones with Aunt Dixie and Floyd with the red shoes?

Honey Bear is the story of a big and black and boogy bear who steals a pinky, winky baby from a cabin and takes it deep into the dusky, rusky forest. It’s not a book with a product tie-in or a Disney spin-off—the kind of contemporary kids’ book garbage that, if you’re like me, parents can occasionally manage to read aloud while more asleep than awake. Whimsically illustrated by Maginel Wright Barney (sister of Frank Lloyd Wright), Honey Bear is lyrically engaging, like the best of Dr. Seuss, but it’s far from being nonsense. It is thrilling and funny, and it presents a much different kind of morality tale than most children’s books.

Fairy tales are, as a genre, object lessons of what not to do—don’t stray from the trail, don’t disobey your mother—and modern children’s books often conclude with less morbid lessons, like “Be inclusive” or “Go the fuck to sleep.” But Honey Bear is more adult in both its morality and characterization, presenting a maybe-villain who is as horrifying to the baby’s parents as he is attractive to the baby herself. In Willson’s world, being kidnapped by a predator ends up being a wonderful adventure, even if it sends her parents running into the woods with guns. For (spoiler alert) the bear didn’t plan to eat the baby after all but wanted to invite her to a party:

He had gone and found the baby in the teeney,

greeney garden

And had made an invitation in his very Sunday

best

And had taken her to help him have his funny

honey party—

Eating half of it himself and giving baby all the

rest!

While first editions of Honey Bear can cost nearly $200 online, Willson’s work has not persisted in the same way as her brother Meredith’s has. Honey Bear was recently republished by Silver Birch Press, an independent press based in Los Angeles, but it is by no means widely available.

Dixie Willson started writing when she was a child herself: she contributed to her local paper, the Mason City Globe Gazette, at the age of ten, and won a national fiction-writing contest for adults four years later. Her plays were produced by the local theater company, and she eventually began to talk about moving to New York—a plan her parents did not approve of. “They felt she would be happier and better situated if she followed the career of most women, marriage and motherhood,” reported the Globe Gazette in 1941. “They persuaded their daughter that once she was settled down most of her ‘wild dreams’ would disappear.”

So Willson dutifully got married in 1915 but divorced a year later, and she arrived in New York City in 1918 with $9. (She wouldn’t marry again until 1945.) Eight years later, in 1926, she was profiled in The New York Times, which reported that she was by then earning $50,000 a year—nearly $685,000 in 2017 dollars—writing stories that were adapted for films at $10,000 a pop. She had a blonde bob with blunt-cut bangs, and wore a white felt hat and a raccoon coat to her interview—a look reminiscent of “a [J.M.] Barrie character.”

The Times profile—at once glamorizing and infantilizing, making note of both her height (5'3") and appetite (“good”)—makes Willson a bit of a manic-pixie dilettante. But as a journalist, she was both highly skilled and determined in her reporting, often spending extended periods of time immersed in the worlds she was writing about. “When she wrote, she became what she wrote,” her daughter, Dana Willson Briggs, told the Mason City Globe Gazette in 2001. She wrote about entertainment, broadly speaking, which was a beat that ran the gamut from profiling Barbara Stanwyck for Photoplay in 1937 to writing about her own experiences as a chorus girl. For Willson’s book Where the World Folds Up at Night (1932), which follows the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows of the 1920s, she didn’t just interview people who had joined the circus, she joined herself, becoming an elephant rider:

I was feverishly eager to be part of everything. I wanted to swing from the highest trapeze. I wanted to enter the cage of the fiercest lion. I wanted to try my mettle and measure my grit with the rest. I wanted to fit into a place where that steady fearlessness and never-failing courage would be required of me too. If a disregard, a contempt, for the white feather were the only thing the circus has taught me, I should consider it, for that alone, a magnificent association.

Later she attended Trans World Airline’s stewardess school in order to write Hostess of the Skyways (1941), about the women who attended to the rich travelers of the golden age of flying. Her wild dreams simply would not, as her parents had suggested, simply disappear.

The most significant literary influence Willson has had involves Tom Wolfe, surprisingly. It wasn’t that the lived-in style of reporting she practiced helped beget New Journalism—it was again because of Honey Bear. Her writing “galvanized” a young Wolfe, he told Yale Alumni Magazine in 2003. “Honey Bear’s main attraction was Dixie Willson’s rollicking and rolling rhythm: anapestic quadrameter with spondees at regular intervals”—a rhythm that, as both Wolfe and every other person I have showed the book agree, nearly demands to be read out loud:

He would growl and he would grumble, he would

snuffle at the flowers!

He was big and black and boogy, and the neighbor

children said,

If they ever went a-playing in the dusky ruksy

forest

And they found his big old bear-tracks they’d go

scooting home instead!

“I had memorized the entire poem in the passive sense that I could tell whenever Mother skipped a passage in the vain hope of getting the 110th or 232nd reading over with a little sooner,” he wrote. “Oh, no-ho-ho…there was no fooling His Majesty the Baby. He wanted it all. He couldn’t get enough of it.”

Despite being such a galvanizing force in Wolfe’s life as a writer, he called Willson “a writer who never rated so much as a footnote to American literary history.” Yet his own books suggest otherwise: every one of his books contains an homage to her work. Look at the very beginning of The Right Stuff, when Wolfe describes Pete Conrad’s cottage as being set among a stand of pines “with a thousand little places where the sun peeks through”—which is just how Willson describes the woods where Honey Bear takes place.

Similar lines can be found throughout Wolfe’s work. “I’ve slipped a phrase or two from Honey Bear into every book I’ve written,” he said. Willson, in turns out, rates at least a footnote—though she deserves much more.