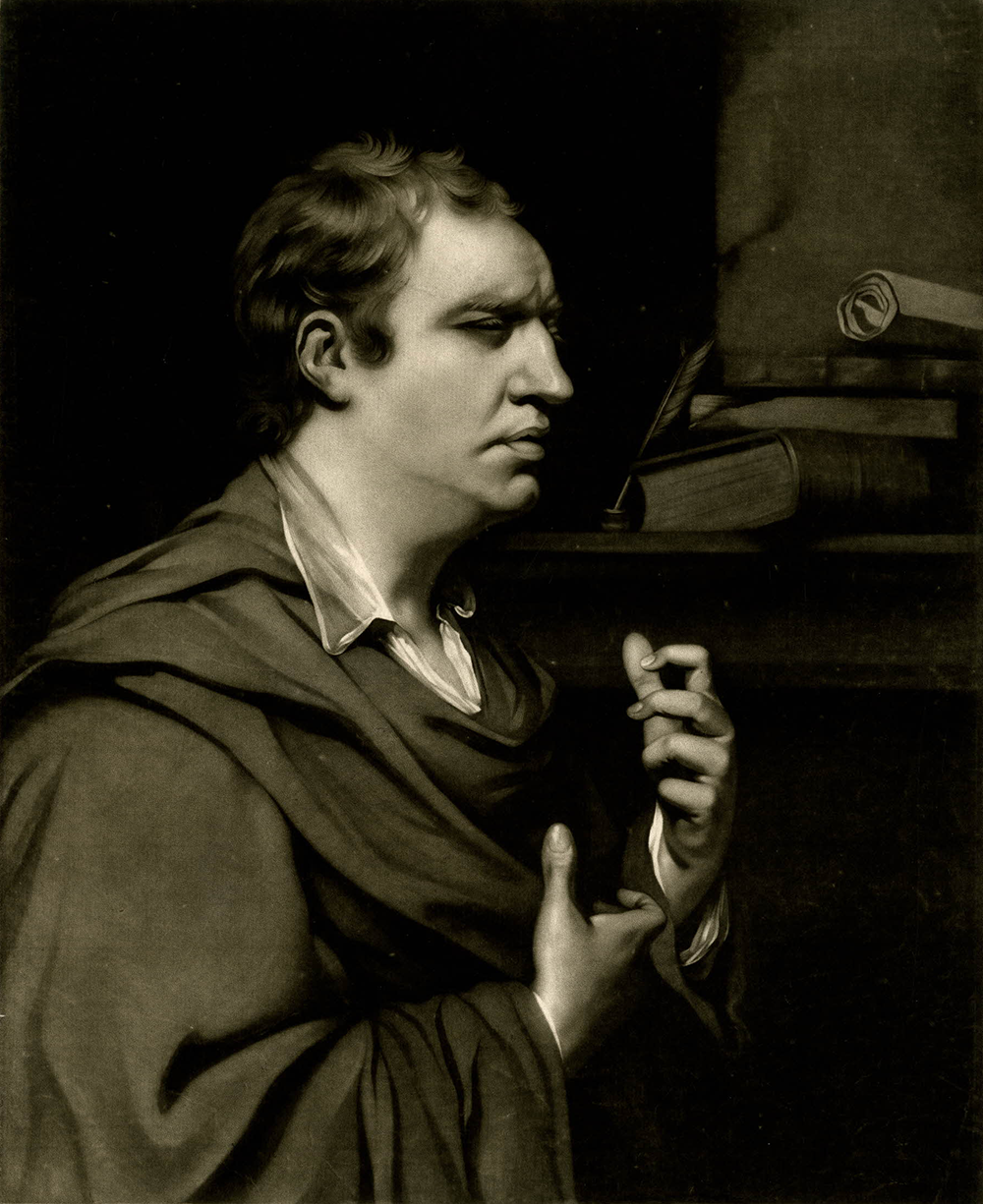

Samuel Johnson, by John Opie. National Portrait Gallery, London.

“The dream of my Brother I shall remember.” Samuel Johnson wrote that sentence in his diary on the morning of January 23, 1759. It’s not unreasonable to assume that he did so with some emotion: his mother had been buried the previous day. Above the note about his brother, Nathaniel, he had written a prayer for her:

I commend, O Lord, so far as it may be lawful, into thy hands the soul of my departed Mother, beseeching Thee to grant her whatever is most beneficial to her in her present state.

O Lord grant me thy Holy Spirit, and have mercy upon me for Jesus Christ’s sake. Amen.

And, O Lord, grant unto me that am now about to return to the common comforts and business of the world, such moderation in all enjoyments, such diligence in honest labor, and such purity of mind, that amidst the changes, miseries, or pleasures of life, I may keep my mind fixed upon Thee, and improve every day in grace, till I shall be received into thy kingdom of eternal happiness.

I returned thanks for my Mother’s good example, and implored pardon for neglecting it.

I returned thanks for the alleviation of my sorrow.

The dream of my Brother I shall remember.

Nowhere else in his extant writing does Johnson refer to that dream. And nowhere else in his many volumes of diaries does he mention his brother, who had died in somewhat murky circumstances in 1737, aged twenty-four.

So we speculate. And we have plenty of matter with which to work—Johnson’s life was documented like few others. “I believe,” he told James Boswell late in his life, “there is hardly a day in which there is not something about me in the newspapers.” Boswell’s landmark biography was only the beginning: in the centuries since, there have been numerous accounts of Johnson’s life, the earliest by those who knew him, later ones by scholars who made ever more exacting use of the ever greater trove of papers and information on Johnson and his era. Johnson continues to have devotees. He is the subject of societies that attract both fans and scholars. Both his boyhood home and his London house have become museums. Three centuries after his birth, Johnson lives.

Even so, in trying to learn more about Johnson’s dream, we face our perpetual enemies: silence, time, and the burning barrel. Boswell, who might have told us more, was reticent about Johnson’s troubled thoughts, though it’s also possible that he never heard about the dream; Johnson loved Boswell but did not confide in him. After Johnson’s death, Boswell did have access to the diaries, and thus knew about at least some of the internal struggles Johnson faced, but his aim was to present a man who was above that—real and alive in his conversation, as quick perhaps to display anger as to show enthusiasm, but exemplary in his mind and thought, untroubled by the doubts that plague us lesser mortals.

Hester Thrale was a closer confidante than Boswell—until she shocked and disappointed the widowed Johnson by marrying late, thus frustrating his own misguided hopes in that direction—and did know at least something of Nathaniel. In her Anecdotes of Samuel Johnson (1786), published two years after her friend’s death, she wrote:

Of [Nathaniel’s] manly spirit I have heard his brother speak with pride and pleasure…The two brothers did not, however, much delight in each other’s company, being always rivals for the mother’s fondness.

But of the dream she wrote and, presumably, knew, nothing.

What might we speculate? We can start with two premises, both backed by strong evidence: Johnson was a man who felt guilt powerfully, and he likely couldn’t shake a sense that he had not done all he might have for Nathaniel.

Guilt animates a famous incident in Johnson’s life that biographer Peter Martin calls “one of the great images of Johnson’s troubled soul.” That the guilt is familial makes it even more salient. Johnson’s father, Michael, ran a bookshop in the cathedral town of Lichfield, where the family lived. Like many a bookish youth then and now, Johnson found reading books far more interesting than the labor of selling them, and he seems to have done his best to avoid taking shifts either in the shop or at nearby town markets where Michael would set out a stall. According to Henry White, a young clergyman who became a close friend of Johnson’s in the final year of his life, one day Michael, possibly laid low by illness, asked his son to fill in for him at Uttoxeter Market. Johnson refused. “Pride,” he told White, “was the source of that refusal.” But that was far from the end of the episode, either for Johnson or for posterity. Nathaniel Hawthorne was so taken by it that he fleshed it out extravagantly to make a lesson for young readers in his didactic Biographical Stories for Children (1842):

But when the old man’s figure, as he went stooping along the street, was no more to be seen, the boy’s heart began to smite him. He had a vivid imagination, and it tormented him with the image of his father standing in the marketplace of Uttoxeter and offering his books to the noisy crowd around him…He was standing in the hot sunshine of the marketplace, and looking so weary, sick, and disconsolate that the eyes of all the crowd were drawn to him. “Had this old man no son,” the people would say among themselves, “who might have taken his place at the bookstall while the father kept his bed?” And perhaps—but this was a terrible thought for Sam!—perhaps his father would faint away and fall down in the marketplace, with his gray hair in the dust and his venerable face as deathlike as that of a corpse. And there would be the bystanders gazing earnestly at Mr. Johnson and whispering, “Is he dead? Is he dead?”

Our childhood failures, particularly those of character, can haunt us like little else. Hawthorne even goes so far as to suggest that this one penetrated Johnson’s dreams:

Many and many a time, awake or in his dreams, he seemed to see old Michael Johnson standing in the dust and confusion of the marketplace and pressing his withered hand to his forehead as if it ached.

Yet this would be nothing more than a well-remembered incident from childhood were it not for what Johnson did years later (according to Hawthorne, on the fiftieth anniversary of the incident). As Johnson told White:

A few years ago I desired to atone for this fault; I went to Uttoxeter in very bad weather, and stood for a considerable time bare-headed in the rain, on the spot where my father’s stall used to stand. In contrition I stood, and I hope the penance was expiatory.

An account from Richard Warner published in 1802 has Johnson offering more detail, though the sourcing is vague:

Going into the market at the time of high business, [I] uncovered my head, and stood with it bare an hour before the stall which my father had formerly used, exposed to the sneers of the standers-by and the inclemency of the weather.

Johnson was a figure to occasion remark in any setting: large, shambling, prone to physical tics. Hatless and wigless, head down in silence in the rain, amid a bustling market, he must have been the carefully avoided center of attention, an unforgettable image. The monument to Johnson in Lichfield’s market square displays this scene in bas-relief on one side of a plinth. Hawthorne was so taken by the image of Johnson in the rain that he adapted it for The Scarlet Letter, with Dimmesdale the silent penitent.

His father was far from Johnson’s only source of guilt. It shines through the prayers he composed in the wake of his beloved wife’s death, animating them with a pained sense of remorse for things not done, kindnesses not offered, that will be familiar to anyone who has lost a loved one. Nearly all of Johnson’s guilt takes that form: less a regret for actions taken than a deeply religious sense of failing to do what he should have done—fears of squandering what he truly believed were his gifts from God. His journals abound with acknowledgments of failings and resolutions to do better: laments that “this day I have trifled away,” repeated resolutions “to rise early,” reminders to “to do good as occasion offers itself,” even, late in life, “to review former resolutions.” On his twenty-eighth birthday, in what would become an annual habit—and a marker of his abiding preoccupation—he composed a prayer for the year ahead:

I have this day entered upon my 28th year. Mayest thou, O God, enable me for Jesus Christ’s sake to spend this in such a manner that I may receive comfort from it at the hour of death and in the day of judgment. Amen.

Nowhere does Johnson feel so much our contemporary as in his failed resolution-making. Nowhere does he seem further away from our more secular age than in his focus not on self-improvement for its own sake but on the injunctions laid by God.

Though combative in conversation, Johnson was also kind, generous, and loyal—a loving husband to a sometimes quarrelsome wife, keeper of a household that over the years welcomed more and more strange characters who had no other place to go, like the blind poet Anna Williams and the quack doctor Henry Levet. Friendship was powerfully important to him: in a poem of that name he called it the “peculiar boon of Heaven / The noble mind’s delight and pride.” In The Rambler he wrote, “Life has no pleasure higher or nobler than that of friendship”; to let it die, he wrote elsewhere, “is voluntarily to throw away one of the greatest comforts of the weary pilgrimage.” He remained in contact with and loyal to friends of his youth and those who had shown him kindness when he was an awkward young man of no accomplishment. One of his most public acts of compassion seems likely to have been sparked by friendship: asked by his neighbor and friend Edmund Allen to write in support of William Dodd, a clergyman who had confessed to forgery, Johnson quickly undertook a multipart campaign. That it was in vain—Dodd was hanged—doesn’t lessen the commitment.

Yet this man—accomplished, beloved, loyal—feared death and the terrible judgment he was sure he would find there. Boswell records an unforgettable conversation on the subject. “As I cannot be sure that I have fulfilled the conditions on which salvation is granted,” Johnson says, “I am afraid I may be one of those who shall be damned.” Asked what he meant by that, Johnson replied—with, says Boswell, passion and volume—“Sent to hell, sir, and punished everlastingly.” Another time, all but breaking down amid a discussion of death, he cried, “I have made no preparation for the grave. What shall I do to be saved?” His successes, his kindnesses, his good character—all were as naught against his sense that he could have done better, as enjoined upon him by God, with damnation the inevitable outcome of failure.

Which returns us to the subject of Nathaniel. Our knowledge of the life and death of his younger brother is scanty. Johnson biographer James Clifford calls him “at best, a shadowy figure.” Johnson’s notes for his dictionary offer a cryptic clue about Nathaniel’s character: next to a quotation from John Norris’ Miscellanies positing that Jesus suffered more than ordinary men because of his sensitivity, Johnson wrote, “My brother.” Clifford, at least, reads the note as referring to run-of-the-mill men: “Nathaniel was not the kind of man who allowed little things to affect his mood.” It’s hard not to wonder, however, whether (without the presumption this might indicate) he meant to compare his brother to Jesus. Nathaniel was hearty and convivial, but might he also have shared some of his brother’s sensitivity?

Born in 1712, Nathaniel became a bookbinder (an occupation that made up a large part of the work of bookselling in those days), and by 1734 at the latest seems to have taken over the family bookshop from his widowed mother. By 1736 he was running a branch of the shop in Burton-on-Trent. That summer, something happened that seems likely to remain forever obscure but comes down to us as certainly discreditable, perhaps even dishonest. Some biographers have speculated that it involved a minor forgery (which could explain Johnson’s eagerness to help the Reverend Dodd years later). What little we do know comes from a plaintive letter Nathaniel sent his mother on September 30 of that year:

I have neither money nor credit to buy one quire of paper. It is true I did make a positive bargain for a shop at Stourbridge in which I believe I might have lived happily and had I gone when I first desired it none of these crimes had been committed which have given both you and me so much trouble. I don’t know that you ever denied me part of the working tools but you never told me you would give or lend them me. As to my brother’s assisting me I had but little reason to expect it when he would scarce ever use me with common civility and to whose advice was owing that unwillingness you showed to my going to Stourbridge. If I should ever be able I would make my Stourbridge friends amends for the trouble and charge I have put them to. I know not nor do I much care in what way of life I shall hereafter live, but this I know that it shall be an honest one and that it can’t be more unpleasant than some part of my life past. I believe I shall go to Georgia in about a fortnight, cottons things I will send. I thank you heartily for your generous forgiveness and your prayers,which pray continue. Have courage my dear Mother God will bear you through all your troubles. If my brother did design doing anything for me I am much obliged to him and thank him, give my service to him and my sister I wish them both well.

We don’t know for certain what Johnson did or did not do for Nathaniel in his extremity. At the time Johnson was in the midst of watching the slow failure of the school he had opened and was far from flush, should money have been all that was needed. Nathaniel’s tone, however, suggests that other support was just as desirable—perhaps even something as simple as encouragement and a few introductions. Clifford thinks that Johnson perhaps remained reluctant to offer such help because he preferred not to have his brother settle at Stourbridge, where Johnson had lived for a while and made some fairly prominent social connections. He may have feared the taint to his reputation that might arise from the presence of his rackety and unreliable brother. Regardless of the reasons, it does seem likely that Johnson refused Nathaniel. It’s not hard to imagine him, young and with an eye to his own honor and hopes of success, doing so in a high-handed manner.

Nathaniel did not make good on his resolution to move to Georgia, preventing him from joining George Keats in the category of American immigrant brothers of English literary greats. Knowledge of his movements within England peters out at that point, however. Not even Johnson seems to have known much about his brother’s life in the wake of the mysterious incident. Late in life he wrote to a Miss Prowse near Frome, asking if she could have her servants “collect any little tradition that may yet remain, of one Johnson, who more than forty years ago was for a short time a bookbinder or stationer in that town.” Receiving no useful information, he wrote again to supply additional details—yet still not identifying himself as Nathaniel’s brother:

What can be known of him must start up by accident. He was not a native of your town or country, but an adventurer who came from a distant part in quest of a livelihood, and did not stay a year. He came in ’36, and went away in ’37. He was likely enough to attract notice while he stayed, as a lively noisy man that loved company. His memory might probably continue for some time in some favorite alehouse. But after so many years perhaps there is no man left that remembers him. He was my near relation.

If he received an answer, there is no record.

By 1737 Nathaniel was back in the family home in Lichfield. On March 5—days after Johnson and his pupil David Garrick set out on their journey to try their fortunes in London—he died. Speculation has abounded in the centuries since. Surely Johnson would not have left Lichfield at that moment if Nathaniel had been mortally unwell? Given Nathaniel’s despondent tone in his letter to his mother, it’s long been posited that he killed himself. His burial in consecrated ground would seem to rule that out, however, as would the epitaph the militantly honest Johnson ordered inscribed on the family grave, alongside new epitaphs for his mother and father, in his final days of life, when mortality turned his mind to their memory:

With them is their son Nathaniel, born in 1712, whose powers of mind and body held out great promise, but his short life ended with a pious death in the year 1737.

Regardless of the manner of Nathaniel’s death, it’s hard not to imagine that a man as prone to guilt—and in particular to guilt over things undone—as Johnson would not have carried it as a burden.

Though Johnson gave continual thought to the fate of his soul in the afterlife, like more heedless men he neglected the prosaic aspects of death until it was upon him. He made no will until his final days, and even as death’s arrival began to seem inevitable, “he procrastinated that business,” wrote his friend and eventual biographer John Hawkins. Only Hawkins’ reminder that dying intestate would drag his relations into litigation prodded him into action; even then, he so little wanted to attend to the details that when Hawkins presented an outline, Johnson tried to get him to take it away and fill in the blanks for the beneficiaries himself.

About two weeks before his death, Johnson undertook—with the help of his longtime servant Francis Barber—one last act of much-delayed preparation, described here by Boswell:

The consideration of the numerous papers of which he was possessed, seems to have struck Johnson’s mind with a sudden anxiety, and as they were in great confusion, it is much to be lamented that he had not entrusted some faithful and discreet person with the care and selection of them; instead of which, he, in a precipitate manner, burnt large masses of them, with little regard, as I apprehend, to discrimination.

Those final weeks, wracked with pain, saw him standing for hours at the burning barrel. One item that Boswell claims Johnson burned was a two-volume “full, fair, and most particular account of his own life, from his earliest recollection.” His mother’s letters, too, went into the flames. Any word to be found in either regarding Nathaniel became smoke and ash.

Johnson feared damnation. Today, fewer of us than in Johnson’s time are likely to dwell on that risk in our final hours. Many, perhaps most, of us remain frightened of oblivion, however. Have we left anything that will last? How quickly will the memory of our steps on this earth fade? For all his doubt, Samuel Johnson knew from at least midlife, with the publication of his dictionary, that he had made a mark. His name, at minimum, would carry through the years. As he aged, he surely began to realize that more of him would linger at least for a few generations—he had too many well-connected friends who were too fond of an anecdote to let his memory wholly fade. He likely didn’t imagine how long it would last, or how extensively detailed our knowledge of his life would be. I suspect most subjects of contemporary biographies, even those who had lived their lives in public, would be horrified at the display of their most intimate details the form entails today. That there has never been a biography of Johnson that’s not admiring would be only partial mitigation. Yet perhaps Johnson, ever the teacher, would be able to see his life as a lesson, a reminder that, as he put it in The Adventurer, it is “reasonable to have perfection in our eye; that we may always advance towards it, though we know it never can be reached.”

What, however, of Nathaniel? His fate is the one unfairly meted out to the everyday people caught up in the train of the famous, their lives reaching us only to the extent that they intersected theirs. Nathaniel must have had his fears of death, damnation, and oblivion, too. But he had no assurances about his memory. Would he have wanted them, on terms he played so little part in setting? His life could hardly have been more ordinary; even its early close was less uncommon then than it would be now. It is the very model of an unremarked life in the era of record-keeping: were it not for his brother, there would be but a handful of notices of his existence and passing buried in parish registers, unread.

Yet because of his brother, Nathaniel lives, in a sense. Our knowledge is modest. Time denies us key facts. But the hints we have sketch an outline. His wounded letter to his mother suggests a prickly pride, and perhaps a jealousy of his more talented brother. From Johnson himself we have the comment about Nathaniel’s “manly spirit.” What I return to, however, is Johnson’s late-in-life letter seeking information about his brother, with its thought that Nathaniel might be remembered, one presumes fondly, in a local bar: “He was likely enough to attract notice while he stayed, as a lively noisy man, that loved company. His memory might probably continue for some time in some favorite alehouse.” That prospect carries a kind of pathetic beauty, as does Johnson’s acknowledgment of it. There are worse fates than to be remembered for a time in one’s local.

The dream of my Brother I shall remember. We can’t know the dream. We never knew the brother. But we’ll remember him.