Cape Finisterre, on the western coast of Galicia, Spain, 2017. Photograph by Deensel. Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

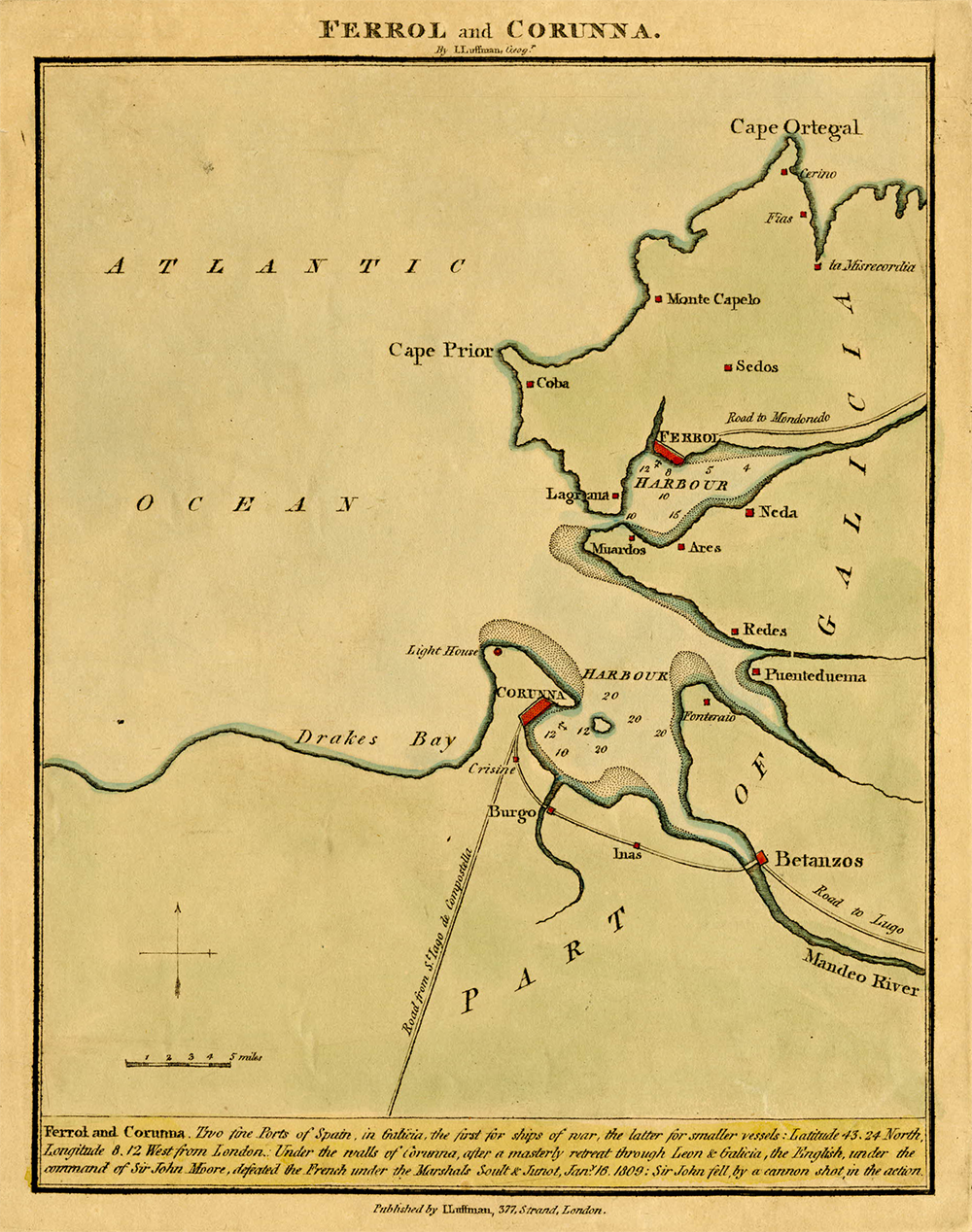

It seemed hard to believe when we did the measurements at school: Galicia has 930 miles of coast. More than Andalusia, more than all of the Balearic Islands put together. Zoom in and the shoreline reveals an aversion to straight lines; it comprises an uncompromising welter of recesses and tiny bays, ideal for entering and leaving unseen. The succession of shelves and rocks that skirt it could almost have been designed for ships to run aground on. One of its stretches is called Costa da Morte—the Coast of Death. And it is on the Costa da Morte that this story begins.

There was a time when the only interaction between the villages and towns in the area—most of them nestled away, sheltered from the scouring Atlantic winds—took the form of rivalries between the fishermen’s guilds. The remoteness of Galicia brought about a unique accent that other Spaniards often struggle to understand. The jewel in the crown is Cape Finisterre—the end of the world as far as the Romans were concerned; to the Greeks the point from which Charon the ferryman set off across the Styx; and the place where the Christian Camino de Santiago begins. For most visitors today, it is simply a charming promontory jutting into the ocean. And, it just so happens, a nice steep headland for bringing in contraband.

The people of Costa da Morte, which runs roughly from the city of Coruña to a little way past Finisterre, have always depended on the sea for their livelihood. On fishing and on trade, but also on passing merchant vessels; they would not always wait to get their hands on the cargo at the principal ports of Corme, Laxe, Muxía, or Camariñas, often choosing to go out raiding instead. Or they could just keep an eye out for any wreckage that might wash ashore.

Any attempt to count the ships that have sunk off Galicia is itself destined to flounder. There have been 927 documented cases since the Middle Ages—“If only,” locals say to that. A researcher named Rafael Lema has written a meticulous compilation of these stories entitled Costa da Morte, un país de sueños y naufragios (Coast of Death: Country of Dreams and Shipwrecks), which summarizes some of the most surprising incidents.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the English merchant vessel Chamois ran aground near Laxe. According to local fable, a fisherman went to the aid of the crew, calling out when he drew close to see if the captain wanted assistance. The captain, thinking he was being asked the ship’s name, answered “Chamois,” and a wondrous linguistic short circuit resulted: the fisherman understood him to be saying that the ship’s cargo was cattle (bois in Galician) and hurried back to land to tell his compatriots. In no time at all they had sailed out in their hundreds, armed to the teeth—to the horror of the bedraggled Englishmen.

Around the same time there was the Priam: when it ran aground, the gold and silver watches that spilled onto the beach were gone within a matter of hours. A grand piano also washed up, and the locals, mistaking it for another chest, hacked it to pieces. They had never laid eyes on such a thing before.

The popular story of the Compostelano does not strictly concern a shipwreck. She maneuvered expertly to enter the River Laxe and, coming to landfall, ran into a sandbank off Cabana beach. When the locals went down to take a look, they are said to have found a cat on board but no sign of any crew.

One of the worst tragedies took place in 1890, when the English vessel Serpent went down off Camariñas and its crew of five hundred perished. Their graves can be found in the nearby English cemetery, positioned scenically between beach and cliff. Twenty years earlier the Captain had sunk off Finisterre, and no fewer than four hundred men lost their lives.

The horror of shipwrecks did not always take the shape of drowned men. In 1905 the Palermo, its hold full of accordions, sank near Muxía. The onshore breeze was said to carry chilling, ghostly strains that night.

In 1927 the Nil beached near Camelle, its hold full of sewing machines, fabrics, carpets, and wagon parts. The first thing the ship owners did was to employ some local people to guard the cargo. Little good that did: others came and stripped the vessel in a matter of days. The Nil also happened to be carrying boxes of condensed milk. According to the accounts, the locals had never seen condensed milk before, and mistook it for paint. When they took it home and began daubing it on their houses, an infestation of flies followed that was of biblical proportions.

The instances outside living memory also include the staggering 1596 case of the Spanish Armada: twenty-five vessels sunk, at a cost of more than 1,700 lives. Reports at the time paint the direst of pictures, with bursts of lightning illuminating a watery scene littered with corpses, shattered pieces of ships, and men crying out as the waves claimed them.

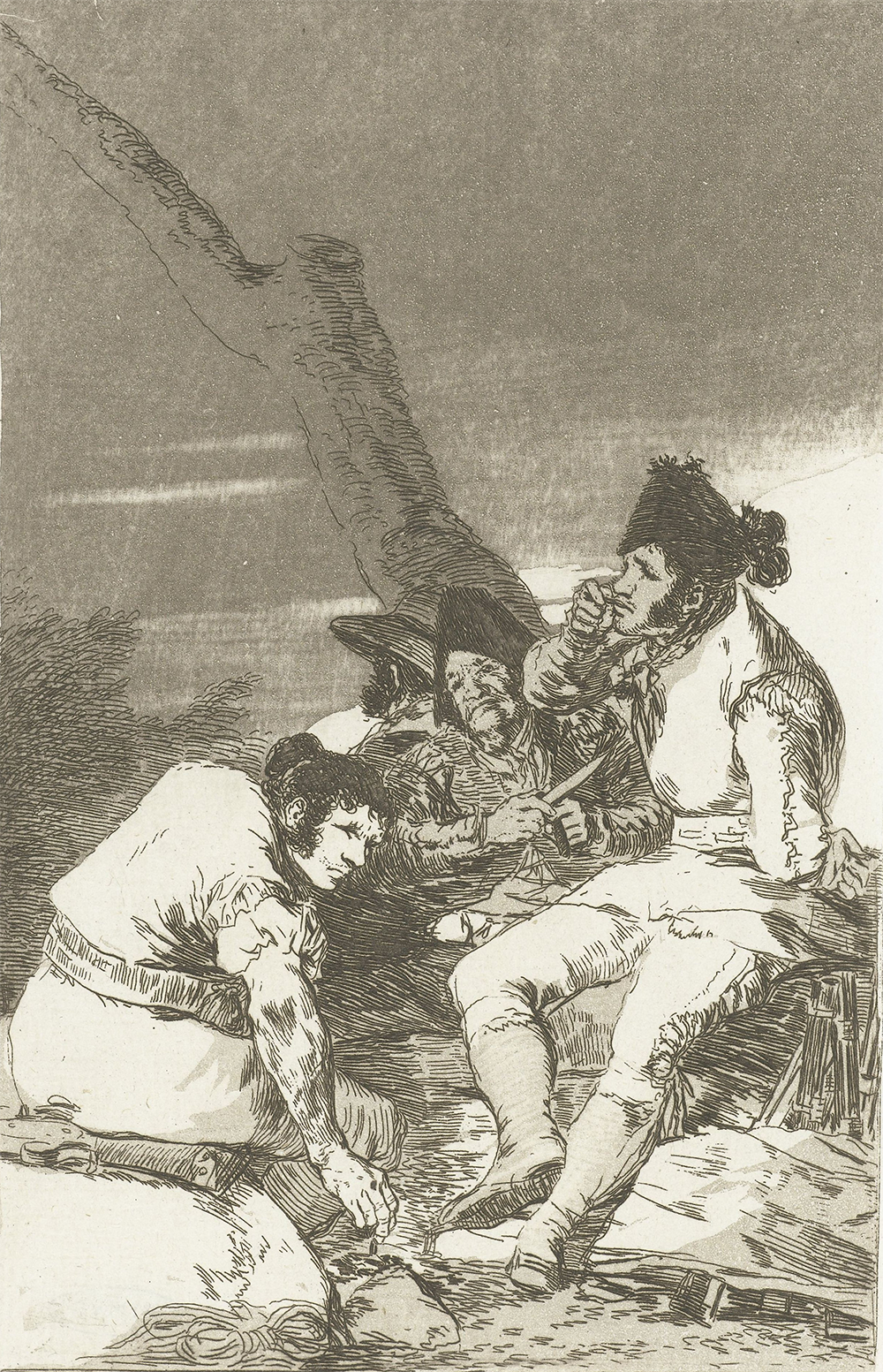

The sailors on the Revendal, Irish Hood, and Wolf of Strong—the three English ships to be wrecked off the Costa da Morte in the nineteenth century—were found mutilated on the beaches. Their fates were sealed by local raqueiros, land pirates who made it their job to throw ships off course before going aboard. They would light pyres or hang torches from beacons placed at strategic points along the clifftops. When the ships ran aground, they rowed out and slaughtered the crews. Most of the victims were Englishmen, and it was not long before word reached those shores. At the turn of the twentieth century, the writer Annette Meakin, a friend of Queen Victoria Eugenie, horrified at the accounts, came up with the striking appellation of the Coast of Death. It stuck. British newspapers were soon running articles about the dreaded area, and it was from there that the Madrid press got hold of the story, and, back-translating to Costa da Morte, began peddling the title too. Westminster soon sent requests to Spain asking the authorities to take measures against “these pirate mafias.”

“There was never a mafia,” says Rafael Lema. In his opinion, these were isolated incidents, and the stuff of local legend was just that: “There is nothing in the records to suggest the existence of any pirate organization that systematically went around plundering ships.” Although the tales of shipwrecks are open to debate, they still give a sense of a society and an economy taking shape over several centuries on the basis of easily available, and usually not paid-for, cargo.

While ships were being plundered on the Costa da Morte—or allegedly being plundered—those inland were quick to take advantage. Here the facts are not open to debate or mythologizing: from medicine to hard currency, comestibles to electrical appliances, and from consignments of metal to weaponry and immigrants, over time all manner of merchandise has found its way through a raia seca (the dry strip/border), as the areas of land that join Galicia and Portugal are known.

The Luso-Hispanic border at these latitudes is famously diffuse. Very old cultural and linguistic overlaps exist between the countries, and there is no clear geographical dividing line. As recently at the nineteenth century some of the inhabitants in the remote villages between Verín and Chaves did not know which country they were citizens of. Nor did they care very much. The most extreme example of this kind of statelessness was in an area called Couto Mixto.

Santiago, Meaus, and Rubiás were the three villages that made up Couto Mixto, a remote and mountainous triangle covering an area of twenty square miles. This desolate area was declared a “murderers’ corner” in the Middle Ages, the same status given to a number of regions that were either situated in remote borderlands or decimated by plague or war and then repopulated with freed prisoners. Some one thousand people installed themselves in Couto Mixto in the eleventh century, and in time it began to operate as an autonomous zone. Both the earldom of Portugal and the kingdom of Galicia renounced any claim to it, leaving the people there in territorial limbo.

When Galicia was annexed by the kingdoms of León and Castile at the turn of the twelfth century, Couto Mixto’s peculiar lack of definition became starker still. From the thirteenth century onward, with no Portuguese or Spanish kingdoms laying claim to the area, the inhabitants effectively began functioning as independent subjects: they elected their own representatives, paid no taxes, and were exempt from conscription. With no official treaties concerning the area, all sides accepted its de facto self-sovereignty. And so Couto Mixto also became a free-trade zone, untouched by the fledgling Spanish Guardia Civil and the Portuguese Guarda de Finanzas alike. The so-called special route that bisected it was a smugglers’ paradise.

This geopolitical limbo carried on until 1864, when Spain and Portugal signed a boundary agreement as part of the Treaty of Lisbon: the border that was established, from the mouth of the River Miño to that of the River Caya in Guadiana, lay not on one side or the other of Couto Mixto but down the middle of it. It spelled the end of this Galician Andorra, whose independence had lasted eight centuries and was the subject of a film by Rodolfo González Veloso called Rayanos: The Last of the Free Galicians.

The treaty marked the line that today—in official terms—still separates the Spanish province of Ourense from Portugal. Families were split in two, though many ignored the decree and simply went on observing the same property boundaries as always. In some places neighbors would have yearly meetings to decide on the new boundaries, according to crop demands or new constructions that had been built. So while the authorities enforced one border, the locals operated according to their own agreements. Following the Civil War (1936–39), the border was manned, putting an end to its hitherto permeability and officially making illegal the import and export of all goods. Shepherds were the only people permitted to cross without registering at the border posts. Some, once they had crossed a raia, did not come back.

The newly rigid border also marked the clear inequalities between the peoples on either side: in postwar Spain, rural areas such as Galicia were plunged into poverty, while in Portugal the standard of living was relatively high. Not only did Galicians have to make do without medicines and petrol, there was a shortage of foodstuffs, electricity, and machine parts. Coffee and lighters became luxury commodities. The locals, looking out by the light of their oil lamps, could see, a short distance away, the Portuguese homes lit by electric bulbs. This was the context for the first-ever concerted smuggling efforts: a consequence of the inequalities between the areas on either side of the border.

There was bootleg food and bootleg medicine, bootleg machinery, mechanical parts and weapons. Those bringing the goods charged forty-nine pesetas for a bundle of food and three hundred pesetas for metals or tools—roughly what an average Galician could earn in a month.

Part of the reason why goods could move across a raia seca with such ease was the complicity of the Guardia Civil. There was nothing abnormal about the sight of smugglers and guardias sharing a tumbler of wine over a game of dominos in the local tavern. The authorities benefited from the arrangement, a marriage of convenience that has carried on into recent times when the area has become a hotspot for tobacco and drug smuggling.

Such activities would halt only during visits of officials from Madrid. The trains that went back and forth between Spain and Portugal began running at their allotted speeds, and not at the usual five miles per hour that allowed handovers to take place. When the Madrileños were around, people would remove the white handkerchiefs from their windows: the coast was no longer clear. There would be a hiatus of a few days, after which, with the officials safely back in the Spanish capital, the locals could once more obtain penicillin (which the Portuguese brought in from Brazil), as well as coffee, ham, salt cod, and cooking oil. English headscarves even made it across the border, destined to be worn by ladies in the Galician market towns of Ourense and Vigo. Clearly, far from being looked down upon, smuggling was an activity to which respect was attached—prestige, even. In the postwar depression that gripped Galicia, contraband was also a means of survival.

During World War II the area became an international source of tungsten, a metal crucial in the building of German armaments. The specialist miners of tungsten in a raia went on to sell it, at times for prices matching that of gold, to “the blondies,” as the Nazi envoys were known. Before the war, tungsten was worth thirteen pesetas per kilo, but so great was the demand from the Third Reich that the price shot up to three hundred pesetas per kilo. Dozens of Ourense families became rich during those years. This localized boom provided the material for a novel, Febre (Fever), by Galician writer Héctor Carré: the Galician border is depicted as a kind of El Dorado, with tungsten miners competing for the spoils. Indeed, at the same time as the Nazis were in the area, resistance fighters who still opposed Franco were hiding out in the Galician hills; they were another source of income for the locals, who sold them contraband Portuguese provisions. There has lately been a resurgence of interest in that singular time, with the Galician Council and the Tourist Institute in Porto working together to uncover the tungsten-smuggling routes—a venture that is to be commended, especially in a place like Galicia where forgetting is what people do best.

Reprinted with permission from Snow on the Atlantic: How Cocaine Came to Europe by Nacho Carretero, translated by Thomas Bunstead, published by Zed Books. © Nacho Carretero. All rights reserved.