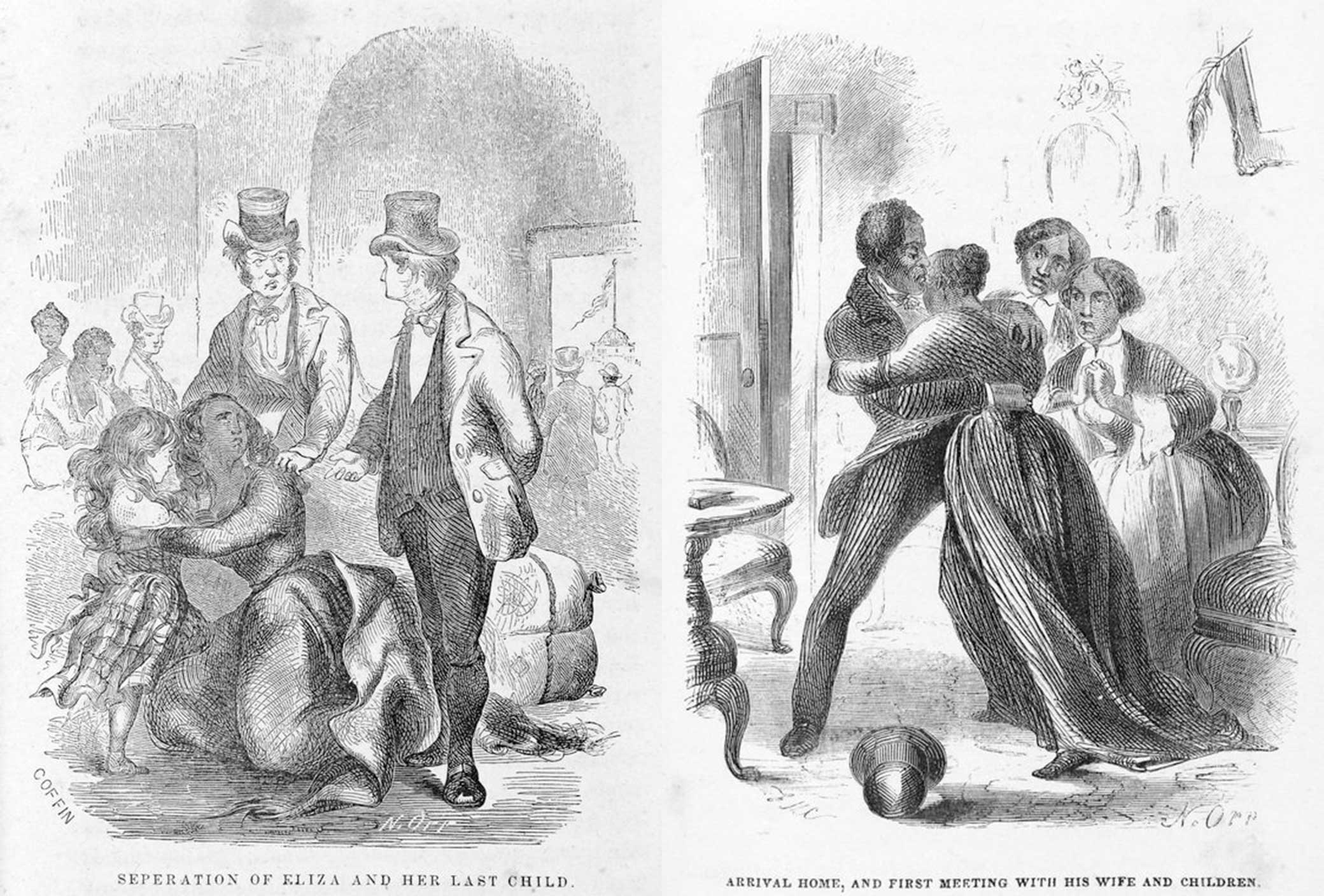

Illustrations from Twelve Years a Slave, by Solomon Northup, 1853. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division

Because of the cultural endurance of the “suffering slave” in antislavery texts formerly enslaved authors may have been reluctant to write about feeling unmitigated joy in bondage both because it perpetuated the myth of the happy slave and it defied the rules of the slave narrative genre and thus their abolitionist audience’s expectations. This authorial quandary surfaces in many slave narratives, as most references to happiness during slavery were accompanied by qualifying statements. When chronicling how her grandfather fell in love with an enslaved woman amid the “sorrow and hopeless toil” of bondage, Mattie Jackson did not describe their relationship as one of unadulterated joy; rather, she noted that “they lived as happily as circumstances would permit.” This careful wording insinuated that there were limits to the amount of happiness that was possible during the “hopeless…circumstances” of enslavement.

The notion of circumscribed happiness was often invoked when formerly enslaved people described being sold. To refute both the fantasy of the kind slaveholder and that of the happy slave, authors of slave narratives were explicit that even if their owner changed, any happiness they felt was relative because they remained enslaved. For example, when Solomon Northup, author of Twelve Years a Slave, was sold to a cruel man named Tibeats, Northup stated he was “doomed…to lead no more the comparatively happy life” he had while enslaved by a Mr. Ford, while abolitionist Sella Martin recalled that when his family was bought by Dr. C. that “for three years [they] were as happy as it falls to the lot of slaves to be.” Neither Northup nor Martin unequivocally stated that they had been content in bondage; instead they maintained that any joy they experienced was “comparative,” conditioned upon their enslavement. They could only be “as happy” as enslaved people could be, their potential happiness constrained by “the lot of slaves.”

Frederick Douglass disavowed feelings of joy while in bondage even more forcefully, stressing how dangerous he thought it was to depict unreserved enslaved happiness. Douglass specified that “much of the happiness—or absence of misery” that he felt while enslaved by a Mr. Freeland was due to the “ardent friendship of [his] brother slaves” and the love they bore for one another. Despite these strong, supportive bonds he “hated slavery” so intensely that in the last few years that he was in bondage he was “not only ashamed to be contented in slavery, but ashamed to seem to be contented.” Rather than unconditionally aver that he had felt some joy while enslaved, Douglass tempered his admission of “happiness” by claiming that he had only experienced “the absence of misery” and that the two were not synonymous. Over time Douglass came to see that purported “absence of misery” as false and shameful.

With the benefit of hindsight he denied having ever felt happiness while in chains, and he even decried feigning contentment. Published in the mid-1850s, as conflicts between abolitionists and proslavery advocates grew more aggressive, Douglass’ narrative stated that desire to repudiate any happiness he had felt in bondage, and his implicit criticism of enslaved people who endeavored to “seem…contented,” elucidates how threatening the figure of the happy slave was to antislavery rhetoric. He could not admit to feeling unchecked joy, nor did he want enslaved people to perform happiness, or even appear content, lest it give members of the slavocracy more ammunition to defend the institution.

In addition to challenging the conceit of the happy slave, illuminating enslaved sorrow, and qualifying their definitions of happiness, many formerly enslaved authors also described the often contradictory nature of happiness and sadness for enslaved people. Slave narratives are saturated with scenes portraying moments of joy amid feelings of sorrow and of moments of sorrow amid times of joy. Depicting the complex ways that enslaved people experienced those feelings was another rebuke to the legend of the happy slave and to all the simplistic feelings that fictitious invention represented. In his discussion of the cathartic role of singing, Douglass observed how song was able to capture how antipodal emotions could intertwine for enslaved people. He recalled that enslaved people “would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone,” thus “revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness.”

Other authors asserted that rather than existing simultaneously, “the highest joy and the deepest sadness” were often inverted for enslaved people. This meant that events that were celebrations for free people could be mournful for enslaved people, while situations that free people met with sadness might be cause for joy for people in bondage. For example, holidays enjoyed by free people often triggered entirely different sentiments for enslaved individuals. Harriet Jacobs, author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, explained how enslaved families could be divided on January 1, as slaveholders rented out enslaved people for yearlong contracts. Jacobs spoke directly to her readership, declaring, “O, you happy free women, contrast your New Year’s day with that of the poor bondwoman!” While for free people “the day is blessed,” full of “friendly wishes…and gifts,” Jacobs noted that for enslaved mothers “New Year’s day comes laden with peculiar sorrows.” In the sentimental era, flipping the affective script in this fashion to reverse the traditional valence of feelings and emotional occasions would have been powerful for readers. The frequency with which formerly enslaved authors illustrated how “the highest joy and the deepest sadness” were compounded or switched for people in bondage also confirms that many authors saw this as a defining trait of enslaved emotions.

Nowhere were the conflicting emotions of enslaved people thrown into sharper relief than in slave narratives’ discussions of rites of passage like courtship, marriage, and childbirth. Rather than portraying them as happy occasions, authors delineated the different associations these life events held for enslaved people. In his 1849 narrative Henry Bibb recalled his hesitance to marry, or even court, an enslaved woman, fearing that their union would only serve to “obstruct [his] way to the land of liberty.” Douglass concurred that love could limit rather than liberate, arguing that “thousands would escape from slavery, who now remain, but for the strong cords of affection that bind them.” Jacobs experienced firsthand that falling in love in bondage produced more anguish than joy, asking her reader, “Why allow the tendrils of the heart to twine around objects which may at any moment be wrenched away?” A number of authors of slave narratives conceded that love had brought them a glimmer of joy, but this was typically immediately accompanied by their recollections of the inevitable heartbreak for enslaved lovers. Once again formerly enslaved people warned their sentimental readers that they should not expect a happy romantic story; instead their experiences of love were laden with ambivalence.

Slave narratives also depicted the mixed emotions enslaved people had about becoming parents. In her narrative of her journey to freedom, Elizabeth Keckley expressed hesitation about motherhood because she “could not bear the thought of bringing children into slavery—of adding one single recruit to the millions bound to hopeless servitude.” Jacobs was also loath to have children because she “shuddered to think of being the mother of children that should be owned by [her] old tyrant.” This reluctance did not subside when her first child was born; she described her feelings for her infant son as “a mixture of love and pain.” Amid her love for the newborn she “could never forget that he was a slave,” which cast “a dark cloud over [her] enjoyment.” Enslaved fathers experienced similar complicated sentiments. After his daughter was born Bibb did not feel the joy that might be expected of a free man who had become a new father because he could not “look upon the dear child without being filled with sorrow and fearful apprehension of being separated.” Even once he became free Bibb confessed that he had “to lament” that he was “the father of slaves.” Over the course of the nineteenth century more importance was placed on children and childhood, which would have made these authors’ anxieties about parenthood all the more harrowing for their audience.

Formerly enslaved authors argued that even reunions between siblings, spouses, or parents and children were not purely joyful if they occurred in the confines of slavery. After successfully running away Bibb dared return to the South to see his wife and child. But his homecoming was marred by warring emotions, as he recalled that “the sensation of joy at that moment flashed like lightning over [his] afflicted mind, mingled with a thousand dreadful apprehensions” known only by the “heart-wounded slave father and husband.” Leonard Black, author of The Life and Sufferings of Leonard Black: A Fugitive from Slavery, experienced these clashing feelings when he got to see four of his brothers for the first time in many years. Black noted that he “was glad to see [his] brothers, but yet [he] was a slave,” so even this momentous event left him depressed, “crushed by the cruel spirit of slavery.” In depicting how supposedly joyous occasions were freighted with sorrowful or competing emotions, former slaves stressed that in bondage there could be no purely happy moments.

Formerly enslaved people also outlined how occasions that might be tragic for free people might be celebrated by the enslaved. This was exemplified in scenes that discussed how it felt when an enslaved loved one ran away, was sold, or died. Jackson bore witness to both her sister and her father running away to seek freedom, but rather than depicting this as a tragic loss, Jackson emphasized how happy her remaining family was to know that their loved ones would be free. To avoid being punished Jackson’s mother even “pretended to be vexed and angry” in their owner’s presence when she was told that her eldest daughter had run off. But Jackson saw how her mother truly felt, describing “how wildly mother showed her joy at Nancy’s escape when [they] were alone together.” Her sister ran away when Jackson was young, but it left a distinct impression on her. Beyond teaching her to conceal certain emotions from slaveholders, Jackson’s mother modeled the complexities of love for her daughter, showing Mattie that one could rejoice at the loss of a family member if it meant that they had escaped enslavement. This early lesson was repeated a few years later when Jackson’s father ran away rather than be sold away from his family. Jackson would “never forget the bitter anguish of [her] parents’ hearts…or the profusion of tears” they cried when her father came to say goodbye. “The parting was painful,” but Jackson explained that her mother even helped her husband implement his plan for escape because she wanted him to be free. As a child Jackson repeatedly saw the lengths one might go to in order to see a loved one become free, even if that meant relinquishing them forever, and that such an occasion could be met with acceptance and joy.

Nowhere was the reversal of traditional sentimental emotions clearer than in slave narratives’ discussions of how death might be welcomed rather than grieved. Jacobs observed that she “had often prayed for death” and even found herself wishing that her newborn child might die too, claiming that “death is better than slavery.” Northup expressed similar fatalistic sentiments throughout his narrative. After watching Patsey recover from a savage whipping by their owner, Northup opined that “a blessed thing it would have been…had she never lifted up her head in life again.” Northup pined for death himself, noting that there were multiple times in bondage “when the contemplation of death as the end of earthly sorrow…has been pleasant to dwell upon.” Just as Jackson’s family rejoiced when family members escaped to freedom, authors of slave narratives painted the death of an enslaved person as a “pleasant” or “blessed” event, not a tragedy. Taken together these depictions of the inversion of sorrow and joy felt by so many enslaved people recapitulated the horrors of slavery while also repudiating any claims that enslaved people led lives of simple, blissful contentment.

Though Northup detailed the suffering endured by enslaved people, he was clear that he was not merely falling into the reactionary trap of claiming that enslaved people were miserable in order to counter the myth of the happy slave. Rather than accept proslavery fictions of contented slaves, Northup rejected the debate itself. In his narrative Northup opined that “there may be slaves well-clothed, well-fed, and happy, as there surely are those half-clad, half-starved, and miserable; nevertheless the institution…is a cruel, unjust, and barbarous one.” Instead of responding to slaveholders’ fantasies of merry slaves with tales of unrelenting woe, Northup contended that even if some enslaved people were happy, which he doubted, a few “happy” slaves did not represent all enslaved people. British journalist James Stirling made a similar point in 1857, writing that “even if ” proslavery authors were right “and the slaves were really as ‘happy’ as they would have us believe,” he was undeterred in his staunch opposition to slavery. He would not be bogged down in a false dichotomy debating “happiness or unhappiness”; he was more interested in slavery “as a matter of right or wrong.” Like Northup, Stirling counseled that happiness was a misleading metric for the health of a society, or of slavery, and should not be used to measure their justness.

Excerpted from Mastering Emotions: Feelings, Power, and Slavery in the United States by Erin Austin Dwyer. Copyright © 2021 University of Pennsylvania Press. Excerpted with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Press.