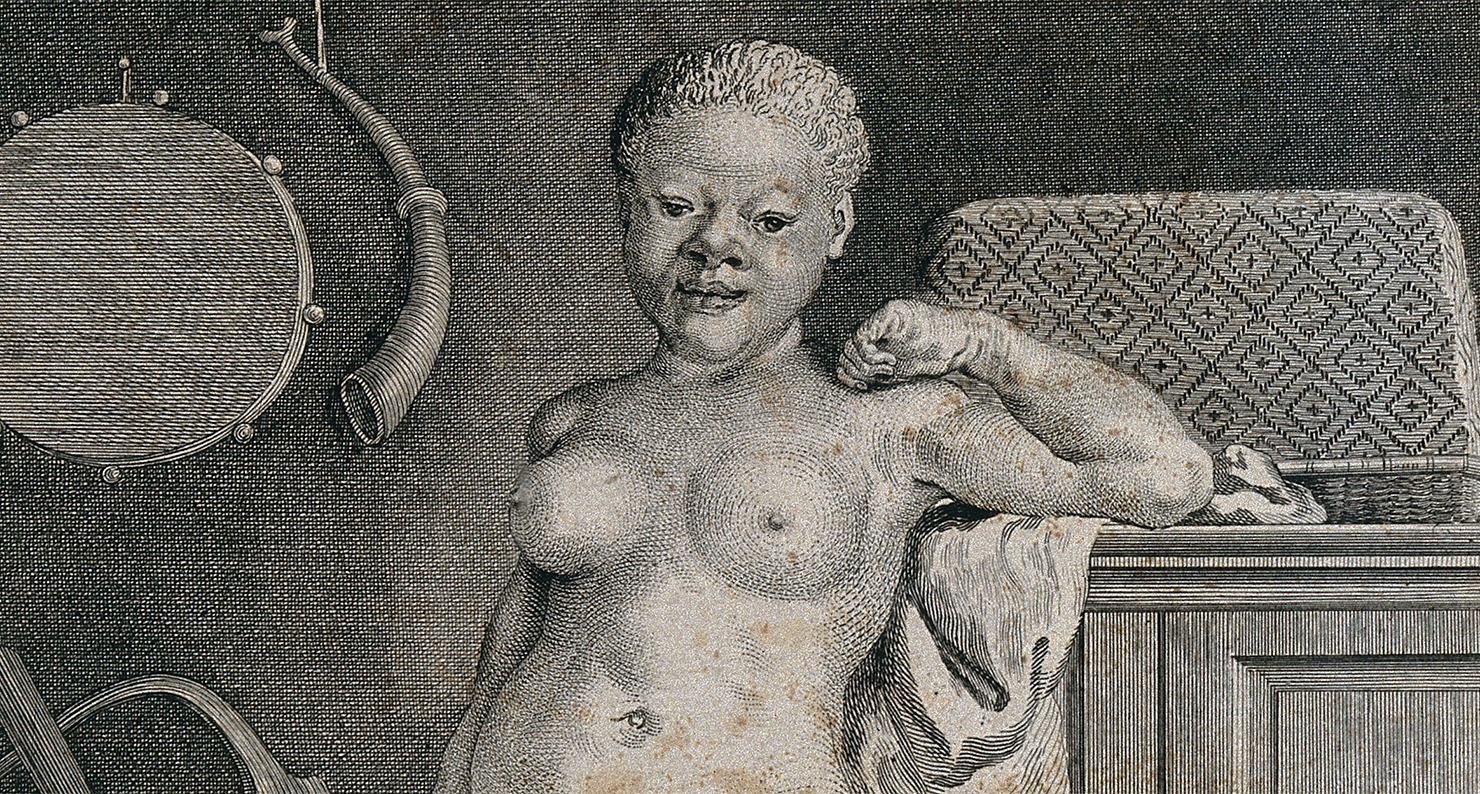

An albino negress, engraving by C. Guttenberg after Jacques de Sève, 1777. The Wellcome Library, London.

Homo sapiens. Has a nice ring to it, doesn’t it? After all, recognizing that every human being is a member of the same species—that we’re all fundamentally made of the same stuff—sits at the center of why there’s any such thing as universal human rights. Homo sapiens, from the Latin, “Wise Man.”

The Swede who named us, however, was limited by the popular wisdom of his time. Failing to recognize that albino African children were, in fact, the same species as European children, botanist Carolus Linnaeus tried in 1758 to purchase a teenage girl in London as a scientific specimen. He thought she was a troglodyte.

February, 1758

Winter locked the river in ice. But light bloomed like beads of sweat inside his greenhouse of specimens—here a rare African violet, there a pineapple from Java. Linnaeus liked to walk through his garden at Uppsala before settling in to a day’s work. After all, he’d trained as a botanist.

That day he had received a letter from one of his students in London, who wrote that a live troglodyte was on display in that city. Linnaeus was revising his notes for an upcoming lecture on “anthropomorpha,” those ape- and man-beasts he thought fell under the same category of Homo, some born entirely of colonial or mythic fancy. While Homo sapiens was subdivided into four racial categories (Americanus, Asiaticus, Africanus, Europeanus) these were still considered the same species. But under Homo there was also Homo ferus, “four-footed, mute, hairy” (such as Peter the Wild Boy) Homo monstrosus(like the mythical Patagonian Giant) and of course, Homo nocturnus, the troglodyte, a “cave-man” with pale skin and poor vision who ostensibly lived without sunlight.

The news excited Linnaeus to no end. What perfect timing! After all, what’s a good taxonomist to do with so few specimens? Linnaeus had monkeys bought from trade ships—likely tiny macaques which he kept chained to a pole in his garden and fed treats—but apes rarely made it to Europe alive. One specimen, a juvenile chimp sent to Edward Tyson in the late seventeenth-century (incorrectly called an Orang-outang), had died on the ship on the way over with some sort of injury to its leg. Since he’d never seen one alive before, Tyson simply assumed the now-expired creature had walked upright like a man, but with a cane.

Linnaeus immediately wrote back to his student in London, begging that he both examine the creature carefully and offer the owner a high price for purchase. Should he succeed, Linnaeus offered him a position in the Linnaean society—Sweden had just knighted the botanist the previous year. He also wrote to John Ellis and Peter Collinson, members of the Royal Society. In this request, Linnaeus outlined specific details he wished the men to examine, as well as a detailed drawing by the illustrator and naturalist George Edwards:

I learn by letters from London, that a Troglodyte, or Homo nocturnes…is arrived in your capital…I therefore most respectfully beg of you to examine this animal with attention…The points on which I chiefly want information are the following:

1. Is the body white, walking erect, and about half the human size?

2. Is the hair of the head white, though curled and rigid, like a moor?

3. Are the eyes orbicular, with a golden iris and pupil?

4. Do the eye-lids lie over each other (incumbents), with a membrane nictitans?

5. Is the sight lateral, and is it only nocturnal?

6. Is there any whistling voice?

7. Is there any space between the canine teeth and the others, either before or behind?

8. What is peculiar in the organs of generation, whether male or female?I wish the excellent Mr. Edwards would make a drawing of this individual, as there is no more remarkable animal, except man, in the world.

The questions Linnaeus asks of his pen pals, though hilarious, aren’t random: they show where Linnaeus got his ideas for Homo nocturnus, this most “remarkable animal”. Having never encountered a live specimen, he’s relying on ancient texts. We’re listening to the voices of Herodotus, and Pliny after him, on the “Troglodyte Ethiopians.” Herodotus first mentions these creatures in his History, mentioning that they lived in caves and fed on lizards, their voices like the “screeching of bats.” Pliny repeats the tale, saying that they would “feed on the flesh of Serpents,” and what’s more, were possibly nocturnal and, if exposed to daylight, “crawled around on their bellies like newborn puppies ”and made “a gnashing Noise, not a Voice, so little exchange have they of Speech.”

The troglodyte was still popular enough in the eighteenth century that he showed up in Montesquieu’s Persian Letters. Even Voltaire wrote an account of a troglodyte, a boy on display in Paris’ Hotel de Bretagne in 1744. Like the London teenager, this was also an albino African child, aged only four or five, the likes of which were typically “diaspora slaves…exhibited by their owners as freaks.” In Voltaire’s piece, the petit Maure blanc in Paris had wooly hair and a yellow membrane where the iris should be—details echoed in Linnaeus’ question whether the troglodyte’s hair was “white, though curled and rigid, like a moor” and whether the eyes had a “golden iris and pupil.”

Though he read Linnaeus fervently and does give the little troglodyte some animalistic features (e.g. a “muzzle” and “wool for hair”), Voltaire broke from Linnaeus’ model of Man. He thought the boy was instead exemplary of a “race of Men” who, although they were “a species that doesn’t resemble ours, like the spaniel to the greyhound” must be considered human: dogs may look differently, but they’re all dogs. Voltaire, therefore, thought of those things under Linnaeus’ Anthropomorpha as a matter of breed. Linnaeus saw greater differences between the troglodyte and humans, not counting her simply as a “little white Moor” but rather a “human monster.” Thus, hearing that such a monster might actually be available in London, Linnaeus was overjoyed.

March, 1758

Nearly a month passed. Linnaeus paced the halls of the university. From abroad, there was continuing support for his new Systema, with questions about Homo especially. Towards the end of March, Linnaeus received a new plate of a chimpanzee or “satyr” from George Edwards, but nothing more about the troglodyte. Unfortunately, Edwards failed to notice the particular position of the beast’s clitoris. Linnaeus, to Edwards:

I am particularly pleased with your admirable figure of the Satyr, which, if I mistake not, will prove a different animal from the Ouran Outang…I wish you would inform me whether there be any space between the canine teeth and the rest; and you don’t say whether the item is female, (or anything about) the nipples and the clitoris.

Linnaeus wasn’t a pervert. His entire taxonomic system had started as a way of organizing plants by their sexual organs. When he moved into animals, this sexual “root” of taxonomic classification continued. That’s why he wanted a better clitoris. And that’s why he’d specifically asked Edwards to carefully examine the troglodyte woman in London, even if that meant lifting her skirts, so that her “reproductive organs” could be suitably mapped.

April, 1758

Spring broke the river in Uppsala, a particular Javanese plant bloomed, but otherwise, Linnaeus’ joy was short-lived. Ellis had visited the subject, but demurred the request for a close examination:

You desire me to enquire whether there is such a creature here as a Troglodyte…I have enquired very narrowly about this animal and cannot find that there is any such here…We had one of these kind of animals here about 20 years ago, which was called a Chimpanzee; this at that time I saw alive, but as it was habited like a young girl, for it was a female, I did not examine so particularly as to answer your questions. All I can remember is that it appeared to resemble the human species more than any I had ever seen exhibited here.

Most eighteenth-century gentlemen had difficulty lifting a skirt of a stranger—even if it was a skirt draped over an especially hairy leg.

July, 1758

“I have called at the place where the young woman that you think is a Troglodyte is kept,” George Edwards wrote in mid-July. The London owner had refused to sell the troglodyte, who was in fact a fourteen-year-old albino girl, to Linneaus or anyone else. Edwards continued:

She is in all respects like a negro, but white like us; her hair is frizzled as the negro’s is, but very white; she is near-sighted, and holds the book very close to her eyes when she reads; she is constantly moving her eyes to and fro, sideways, but this imperfections I have seen in other people; she cannot read in the dark, nor does the sunshine prevent it. She speaks English very well. She is near five feet high, and about fourteen years old; so that if she lives, she will be the common size of women of her own country.

In the eighteenth-century, albino people of African descent were commonly toured in Europe and the Americas, their race-defying pigment and features fetching quite a healthy price. People with the albino condition often have very little pigment in the iris, which can hamper their eyesight, producing not only the “yellowish” iris noted by Voltaire, but also the condition mentioned here by Edwards: nystagmus, a rapid and involuntary side-to-side motion of the eyes, possibly compensating for the eyes’ difficulty in fixing on an object in view, due to an inability to filter the amount of light entering the eye.

Thus, while her hair and skin match Linnaeus’ expectations, her height, eyes, diurnal cycle and ability to speak clearly excluded her from Linnaeus’ prior understanding of the troglodyte. Undeterred, Linnaeus continued to believe in the existence of the troglodyte, leaving it in the Anthropomorpha lecture later that year. For all his wisdom, it’s possible Linnaeus simply believed she wasn’t a troglodyte, after all.