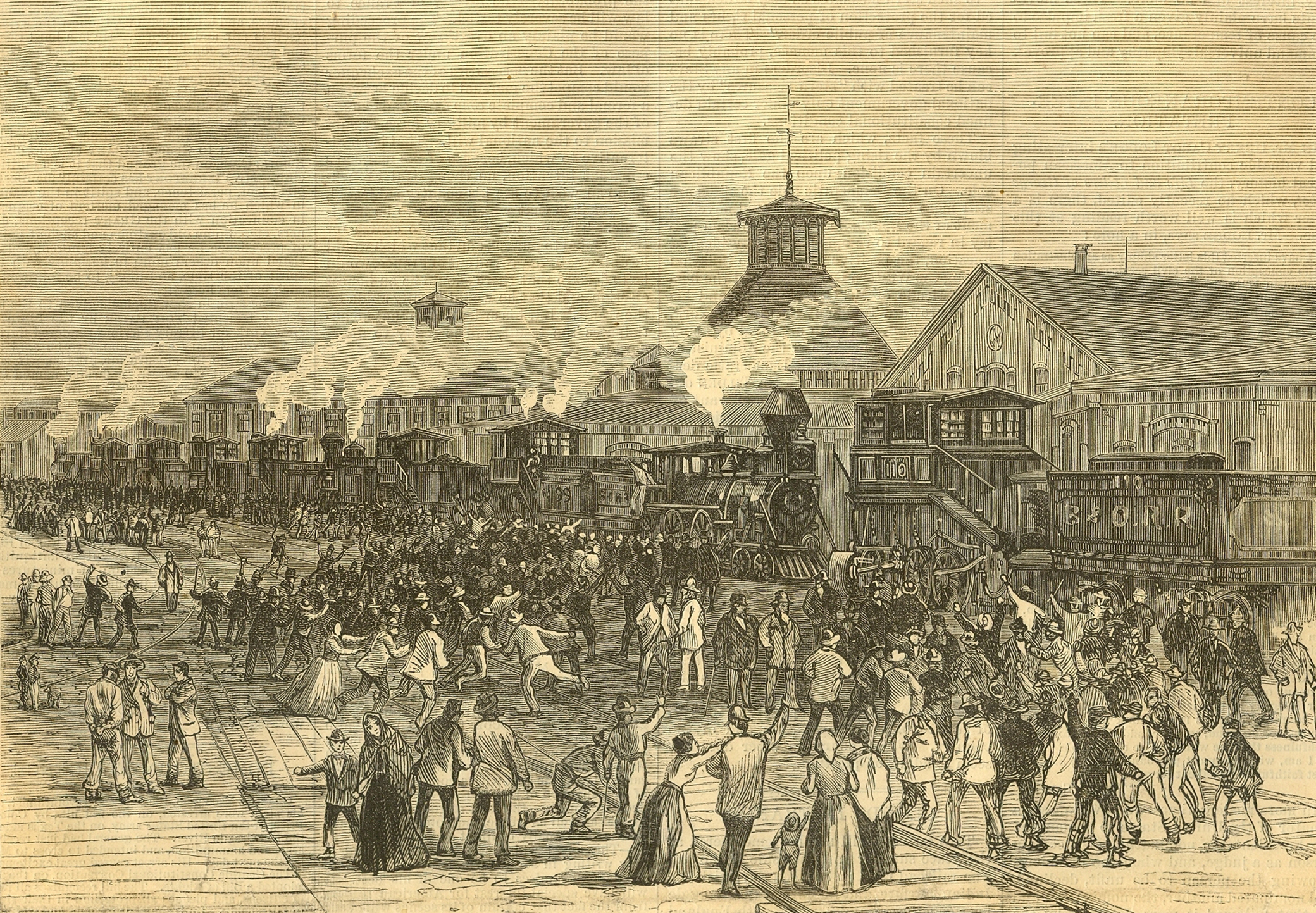

“Blockade of Engines at Martinsburg, West Virginia,” an engraving on the cover of Harper’s Weekly, August 11, 1877.

February 22, 2018, was History Day at the West Virginia State Capitol in Charleston. About an hour before the building opened to the public, I arrived with fellow members of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum team to set up our booth for the event. Founded in 2015, the Mine Wars Museum is dedicated to telling the story of violent labor struggles in early twentieth-century West Virginia. Our annual participation in History Day has been one facet of our ongoing effort to resurrect labor history in the state and construct a more accurate portrayal of a region maligned by stereotypes and inaccurate media portraits.

Yet labor struggles are every bit as contemporary as they are historical. In spite of our early arrival at the Capitol, hundreds of striking teachers had already formed a line at the entrance. By midday, thousands of teachers filled the Capitol complex, holding signs, wearing matching T-shirts, and conducting coordinated chants. Many of the teachers also wore red bandannas. For those of us familiar with West Virginia history, nothing could be more appropriate than wearing a red bandanna at the State Capitol during a strike on History Day.

Long before resistance was a hashtag, it was a bandanna. The red bandanna has been a sartorial thread in West Virginia history, dating back to at least 1877. That year railroad workers in Martinsburg, protesting a 10 percent pay cut, shut down the railroads and sparked the first nationwide strike in American history. Some of these workers began wearing red bandannas around their necks as a symbol of solidarity.

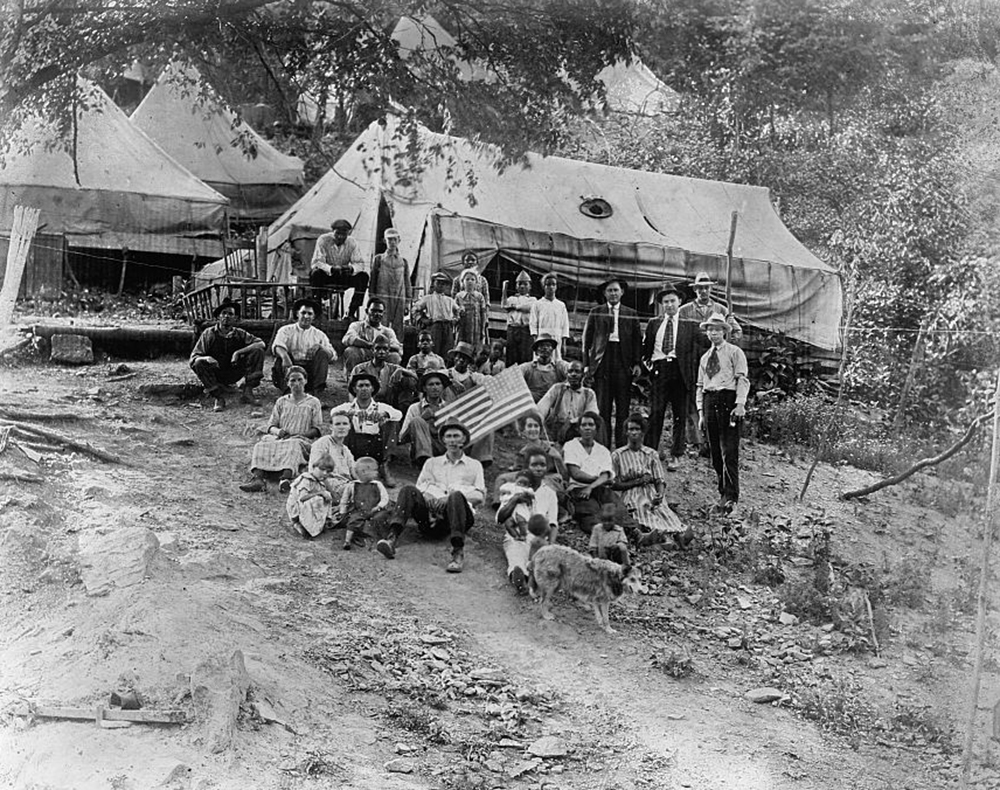

Coal miners adopted the bandanna during the West Virginia Mine Wars, beginning with a major strike on Paint Creek and Cabin Creek and continuing into 1913. Dozens of lives were lost during that strike, as miners and their families turned to violent revolt after they were evicted from company homes and forced to live in tent colonies. At issue was union recognition; the right to be paid in American currency, not company scrip; and the abolition of the local industrial police state known as the Mine Guard System. These same issues were in play in 1921, when the Mine Wars reached its climax at the Battle of Blair Mountain, often described as the largest armed uprising in America since the Civil War. For nearly a week, approximately ten thousand miners assaulted the entrenched defensive positions of some two thousand mine guards and state police along a ten-mile front. Only intervention from federal troops halted the bloodshed.

During the 1921 uprising, so many miners wore bandannas that they were called the “Redneck Army.” Throughout the rest of the century, miners would continue to wear bandannas during strikes. In recent years, environmentalists and historic preservationists in the state have used the red bandanna as a symbol of protest, most notably in their activism against the coal industry and during the 2011 protest march to save Blair Mountain from destruction by mountaintop-removal coal mining.

In 2018 teachers continued the tradition as they donned bandannas and packed into the Capitol complex for the duration of the strike. The term redneck is usually associated with rural and Appalachian stereotypes, but rednecks and red bandannas are in fact symbols of worker solidarity and resistance to abusive corporate power and corrupt politics.

Labor historian James Green has said that West Virginia’s labor struggles created “a culture of resistance” in the mountains that belies the stereotype of the fatalistic, hopeless mountaineer. Indeed, many teachers on the recent strike recalled the Mine Wars and proudly evoked it as inspiration in their own fight. On March 4 state senator Richard Ojeda, an outspoken strike supporter running for Congress this year, tweeted, “In 1921, WV coal miners wore red bandannas and fought for their right to unionize…History always repeats itself.” Jack Seitz, a striking teacher, reiterated the point: “The teachers who have rallied at the Capitol over the past week, many of them sporting red bandannas just like the miners at Blair, recognize this proud history. Legislators who do not recognize this do so at their own peril.”

The bandannas of 2018 may echo Blair Mountain, but machine guns and tent colonies have been replaced by hashtags and memes. One significant difference afforded the teachers is the presence of the internet, which allows strikers to communicate and publicize their concerns. When the Mine Wars in West Virginia began with the Paint Creek and Cabin Creek Strike, martial law was declared three separate times. Hundreds of miners were arrested without habeas corpus, including famed labor organizer Mother Jones. While under house arrest at Paint Creek, Jones wrote letters to sympathetic senators and journalists in order to draw national attention to the conflict. The state government fought back. Governor Henry Hatfield worked on behalf of the coal companies to shut down local newspapers sympathetic to the miners. Nine years later, during the Battle of Blair Mountain, Logan County sheriff Don Chafin’s deputies arrested several journalists and censored their work before it could be sent to newspapers in New York and Washington, DC. Boyden Sparkes, a journalist known for his coverage of World War I, was shot in the leg and arrested by Chafin’s men. He had to watch from his hospital bed as his work was altered to remove “any sob stuff for the rednecks.”

In 2018, by contrast, thousands of teachers instantly broadcast the rallies, the chants, the latest developments, and their own opinions with their smartphones. Teachers began discussing online the possibility of a strike several months before action was taken—unions have come a long way from meeting secretly in the woods outside of company towns. It is encouraging to see how social media has enabled teachers to broadcast their own narrative and use it as a successful tool of resistance. The strike demonstrates that Appalachians’ control over their own narrative is crucial to shaping their future.

The strike also shows how mainstream media narratives of Appalachian politics vastly oversimplify the reality on the ground. West Virginia has been a cornerstone of American labor, but it is also a political quandary, not so easily defined as blue or red. A case in point is that many, if not the majority, of the 2018 strikers identify as political conservatives. In the previous two presidential elections, the Republican candidate carried every county in the state, prompting the national media to dub the area “Trump Country.” I personally know many of the teachers who went on strike, and the majority of those I know are socially conservative women who voted for Donald Trump.

While it is rare to see large numbers of Republicans supporting strikes and unionism, it is not without precedent in West Virginia. In the 1920s, as the Socialist Party crumbled within the state, many labor leaders and socialists gravitated toward the Republican Party. Valentine Reuther, labor activist and father of union leader Walter Reuther, became a Republican. Fred Mooney, a United Mine Workers of America leader and central figure of the Mine Wars, ran for Congress on the Republican ticket in 1924. By the 1932 gubernatorial election, the prolabor faction in the Republican Party had become strong enough to win the nomination for T.C. Townsend, a former coal miner and attorney who defended the miners and their leaders who were charged with treason and murder after the Battle of Blair Mountain.

Townsend ran as a Republican who wanted to diversify the state economy beyond coal. Endorsed by every labor organization in the state, he lost the 1932 election to Herman Guy Kump, a Democrat and pro-industrialist who did not support Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Kump’s election began an eight-decade era during which the state was dominated by Democrats, who did little to check the influence of absentee corporations over the state. Political parties and their ideals evolve from one generation to the next, of course, and in West Virginia Democrats and Republicans often differ from the views of their national party platforms.

Appalachia has a rich history of labor activism, so it is not altogether shocking that conservatives will support prolabor Democrats like Conor Lamb, who recently won a congressional race in Pennsylvania. Generally speaking, Appalachians are a long way from embracing the national progressive agenda across the board. Even though many in the media are calling the teachers’ strike a “progressive” victory, many of the individuals who engineered the victory do not see themselves as progressive at all.

On March 6, 2018, the West Virginia teachers’ strike ended after shutting down public school in the state for nine days. It resulted in a pay raise that will, on average, make life a little more financially tolerable for some of the most underpaid and underappreciated workers in America. Many teachers are now more politically aware and active than they have been in decades, which increases the likelihood they will hold lawmakers accountable for their actions. The strike also let West Virginians connect with their own history in a tangible way, as we aim to do at the Mine Wars Museum. The teachers took control of their own narrative and are forging a new future, in part, by embracing their proud labor heritage.

The teachers may have sparked a strike wave and helped reinvigorate the labor movement; teachers in other states—most notably Kentucky, New Jersey, and Oklahoma—are considering similar actions. Frontier Communications workers in West Virginia and Virginia have just concluded a successful three-week strike. In this way, the teachers’ strike resembles the 1877 railroad strike, which began in West Virginia and spread across the country. West Virginia teachers, with their bandannas and determination, have written a new chapter in the state’s long-standing culture of resistance. For many of these educators, it may be the most enduring lesson they ever teach.