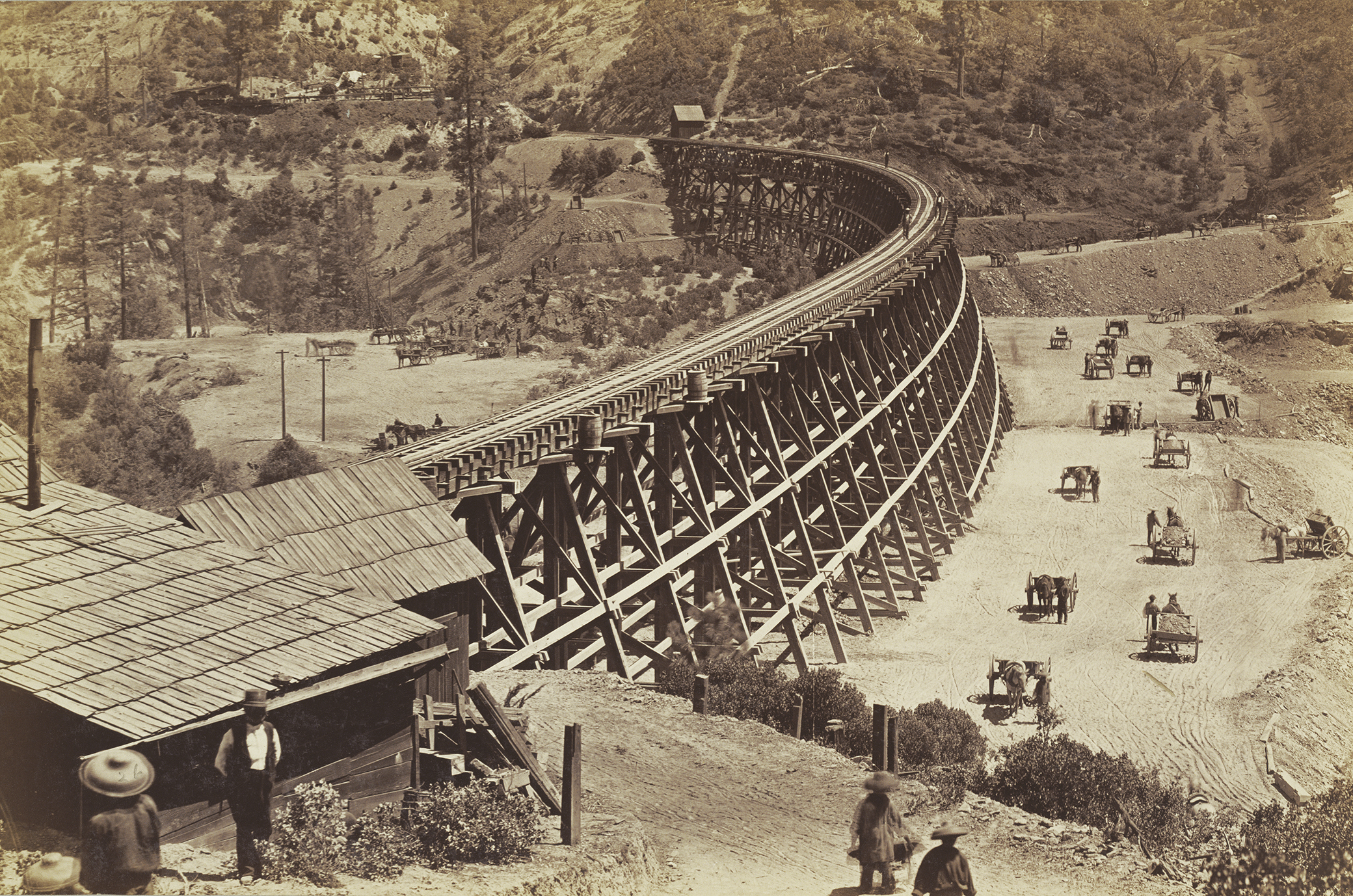

Trestle on Central Pacific Railroad, by Carleton Watkins, 1877. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Charles Fayette McGlashan lived what some might call an exemplary nineteenth-century American life. The sixth child and first son of a French Canadian schoolteacher mother and a Scottish immigrant farmer father who loved music, McGlashan was born in Black Hawk country in Wisconsin Territory on August 12, 1847, less than a year before the area became the thirtieth state of the Union. He spent part of his infancy in the 581-person town of Plymouth in Rock County. But the family soon loaded themselves and their possessions into an ox wagon and headed west, arriving in California in 1854. The gold rush having passed them by, the McGlashans lived modestly. Charles swept the floors of his Sonoma County school to help pay for his education.

In 1872, at age twenty-four, McGlashan married and moved to Truckee, a raucous railroad and logging town just north of Lake Tahoe near the summit of the Sierra Nevada. He quickly became one of the town’s most prominent citizens and remained so for the next six decades. When McGlashan died in January 1931, residents mourned the passing of the man they considered Truckee’s patriarch. Today he is celebrated as a hero and Renaissance man, an attorney and elected official, newspaper owner and editor, well-known historian and author, educator and inventor, and astronomer and entomologist. Most remembrances, however, make no mention of the fact that during his lifetime Charles McGlashan was best known, not just locally but throughout California, as a leading figure in the anti-Chinese movement—a nativist who pioneered a new method of effecting mass expulsion through self-deportation.

Chinese workers first arrived in Truckee in 1864, four years before the town received its name. As the primary labor force for the Central Pacific Railroad in the Sierra Nevada, the Chinese endured brutal work and weather conditions as they cleared roads, bored tunnels, and laid tracks over, and sometimes through, the mountains. They toiled year-round, despite subzero temperatures, avalanches, and snow accumulation of thirty feet or more. Fatalities were common. When the Central Pacific completed the line at the end of the decade, around 1,400 Chinese decided to stay in Truckee. The Chinese, who lived in the same neighborhoods as white residents during these early years, made up close to 40 percent of the town’s workforce.

The history of anti-Chinese violence in Truckee is as old as the town itself. In May 1869 innkeeper Charles Nuce forced an unnamed Chinese man accused of raping his six-year-old daughter to admit to the crime. Nuce then took the man to the Truckee River, shot him, and threw him into the current. When the man tried to crawl out of the water, Nuce struck him with a rock before pushing him back in. “Public opinion is that Nuce did his only duty,” the local newspaper reported. That same day someone shot another unnamed Chinese man in the back and robbed him.

In 1875 a fire of questionable origin destroyed Truckee’s Chinatown, causing $50,000 in damages, the equivalent of more than $1 million today. “Lucky Truckee. Chinatown Holocausted,” the headline read, failing to specify whether the town’s good fortune stemmed from white properties remaining mostly untouched, the near-complete devastation of Chinatown, or perhaps both.

By the following year, some three hundred of the town’s residents, from workers to its most prominent citizens, had formed a local chapter of the Order of the Caucasians, also known as the Caucasian League, to drive out the Chinese. Truckee gained statewide notoriety that summer when late one night seven of the group’s members, clad in black, surrounded and set fire to two cabins full of Chinese woodcutters who had refused to leave the area. The vigilantes shot at the Chinese men as they ran out of the cabin, killing forty-five-year-old Ah Ling. That fall, in a closely watched and highly publicized trial in nearby Nevada City, Charles McGlashan represented the accused men and put fifty witnesses on the stand to provide alibis for them and vouch for their innocence. The all-white jury took just nine minutes to acquit the man accused of murdering Ah Ling, at which point the prosecution dropped the arson charges against the others. Upon learning of the outcome, Truckee’s white residents rejoiced, firing a cannon for each exonerated man. McGlashan returned to town as a hero as well as an emerging figure in what would quickly become a much broader anti-Chinese movement.

The decline of the silver industry in the late 1870s hit Truckee hard since the town had been the principal supplier of lumber to the Comstock mine in neighboring Nevada. The economic fallout contributed to additional anti-Chinese scapegoating and violence. After a fire devastated Truckee’s Chinatown in May 1878, white men marched through the streets yelling, “The Chinese must go!” Less than half a year later, another blaze once again burned Chinatown to the ground. This time white residents threatened the Chinese and gave them one week to leave. Instead, with winter fast approaching, the Chinese began to rebuild. They also armed themselves. But on November 9, a couple of weeks after the fire, hundreds of white men descended on Chinatown and used axes, hammers, and crowbars to break down all of the recently reconstructed houses. The local newspaper reported that as the men went about the demolition work, sympathetic onlookers let out “vigorous cheers” with each “graceful caving in of a roof” or “musical crash of a house.” Within a week and a half, the Chinese had relocated to the other side of the Truckee River just south of town.

Grassroots activists’ subsequent self-deportation drives depended on the fact that, by late 1885, Chinese people throughout the West knew from decades of firsthand experience that the danger of imminent, apocalyptic violence was real. The man most responsible for designing and implementing this supposedly peaceful removal strategy was Charles McGlashan, by then a Nevada County assemblyman and coeditor and copublisher of the Truckee Republican. Aware that the Chinese had defended themselves in the face of expulsion and even brought lawsuits against other towns, McGlashan sought out alternative legal, or quasi-legal, means of removing them from Truckee. “If the Chinese do not leave when so ordered, what are the anti-coolie leagues going to do?” McGlashan and his coeditor (a judge who also happened to be his father-in-law) asked in a November 1885 editorial. They ruled out murder since “it would embarrass the average Californian to have to murder any considerable number of Chinamen” and could also lead to “prison, hanging, encounters with United States troops, and war with China.”

The editors then floated another idea: cut off the queues—the long braided hair—of every Chinese man who remained in Truckee past a predetermined deadline. “The crime of cutting off a Chinaman’s head is a felony, of cutting off his cue is simply a misdemeanor,” a Republican editorial explained, before adding, “but most Chinamen would rather lose their heads than their cues.” A few days later, in a follow-up article titled “The Cue Klux Klan,” McGlashan proposed offering a reward for queues, “as is the case with pelts of wolves, coyotes, and like vermin when they become a pest.” Even though the plan never went into full effect, six weeks later a drunk man severed the queue of a Chinese doctor near the Truckee post office and pinned it to a sign in the center of town for all to see.

From late November 1885 through February 1886 McGlashan and other “conservative, law-abiding property holding citizens” spurred and led Truckee’s “peaceful” anti-Chinese movement. At the group’s first public meeting, those in attendance approved a resolution declaring, “We will use every means in our power, lawfully, to drive [the Chinese] from our midst, and to assist the white laborers of California in forcing them back across the Pacific ocean.” They decided the most effective means of encouraging self-deportation would be to pressure businesses and individuals to fire their Chinese employees by threatening to boycott them if they did not comply.

Two days ahead of the January 15 boycott deadline, McGlashan made clear the stakes. “Either the whites will rule Truckee and the Chinese must leave, or the Chinese must rule and the whites will leave…There will be no compromise, no flag of truce, no cessation of hostilities until the final surrender is made.” Organizers made clear that they would boycott and publicly name and shame any white resident who opposed the movement.

Truckee’s Chinese community fervently rallied in response to defend themselves. They acquired weapons, organized pickets and boycotts of their own, and called on the Chinese Six Companies, a benevolent association in San Francisco, and state and federal officials to intervene and protect them from what one white ally referred to as “McGlashan’s mob.” Little, though, came of their efforts. In the coming weeks, employers fired their Chinese laborers and banks called loans made to Chinese merchants and cut off their access to capital. The result: the departure of hundreds of Chinese from Truckee. When Sisson and Crocker, a large regional firm that supplied laborers to the Central Pacific Railroad, refused to rescind its contracts with Chinese workers, McGlashan and his supporters ramped up their efforts against the company. They sent out circulars calling for a boycott to newspapers and anti-Chinese leagues in cities across the West. Another group threatened to tar and feather the company’s local manager. Finally, on February 11, the firm surrendered. After it did, Chinese merchants requested transportation funds so that Truckee’s “unemployed and destitute” Chinese residents could leave town. White citizens rejected the request, however, and instead offered to pay for transportation if “all the Chinamen in the Truckee basin would depart in a body.” They even promised to throw in an extra $500.

Two nights later McGlashan and a large group of white men built bonfires on Truckee’s main plaza, danced to the music of drums and fifes, and marched through the streets, yelling and brandishing burning torches. People held signs and hung banners from their homes and businesses reading “Law and Order” and “Boycotting Is Victory.”

McGlashan aspired to do more than just expel Chinese people from Truckee—he hoped to remove them from the country altogether. He telegraphed “How to Boycott” instructions to newspapers across California and promoted supposedly nonviolent means of deportation at statewide conventions and conferences, where representatives elected him president of the state convention of the Anti-Chinese Leagues and chairman of the executive committee of the California Anti-Chinese Non-Partisan Association. If enough towns implemented the boycott, McGlashan posited, the Chinese would keep “moving on” until their only option was “to depart for [their] native shores.” And the expulsion campaigns across the West during 1885 and 1886 did push more than fifteen thousand Chinese men, women, and children out of the United States.

Excerpted from The Deportation Machine: America’s Long History of Expelling Immigrants by Adam Goodman. Copyright © 2020 by Adam Goodman. Reprinted by permission.