Seated woman with mirror, c. 1870. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

When new ways of communicating emerged in the nineteenth century, they excited enthusiastic commentary as well as anxieties about self-presentation. One key transformation was the “postal revolution” of the 1840s, which lowered prices for letters and improved their delivery. It enabled an increasing number of Americans to present themselves in writing to friends, family, and the larger world.

However, just as there is a digital divide today, there was something of a postal divide in the nineteenth century, especially in the antebellum period. During the first half of the century, Americans corresponded at wildly different rates—for instance one historian calculates that in the 1850s, North Carolinians sent an average 1.5 letters each year, while residents of Massachusetts sent ten per year. Overall, city dwellers sent more than farmers—New Yorkers averaged thirty letters each year, while Bostonians held the lead with forty-one. Not surprisingly, the literate corresponded more than the illiterate, yet letter writing was still possible even for those who did not read or write, as they could ask or hire others to pen letters for them. While before the Civil War, enslaved people had far less access to the post than whites or free blacks, some slaves nevertheless found ways to avail themselves of it. Despite high rates of poverty and illiteracy, historian David Henkin notes that “slaves and free blacks used the post to a striking degree.” And gradually, over the course of the nineteenth century, more and more people were incorporated into the postal network. This rise of popular access to the post meant a growing number of individuals had to learn how to put forth their ideas and their images and still conform to rules about humility, for they lived in a culture deeply concerned about the vanity of life, in every sense.

Their concern with the vanity—and the frailty—of life was evident in the first lines of the letters they exchanged, for many sensed their mortality acutely and this shaped their motivations and communications. For at least the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century, writers often began their letters with a ritualized affirmation of their existence. Again and again, writers reassured their readers that they were alive. “My Dear Brother—You see that I am still in the land of the living,” wrote Asahel Grant to his brother in 1841. Union soldier Henry Clay Bear wrote his wife in 1863, “I can still say I am in the land amongst the living.” Letters offered their writers a means of declaring their continued presence on earth and in the lives of their friends and families. The hope was a response which would validate that existence, affirm the bonds of affection and social relation through words.

Some commentators suggested that there was almost a moral duty to write family and friends—the failure to correspond was a sign of self-absorption. Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of the popular women’s magazine Godey’s Ladies Book, condemned the “selfishness” of those who claimed they did not have time to write friends and family, reminding readers that the “dear ones at home” were anxious to hear the news of those who traveled far from it.

Because advisers portrayed letters as generous gifts one could bestow on friends and kin, there were fewer fears that they might incite egotism. Letters were governed by different rules than face-to-face social relations. Indeed, many Americans believed the self should be very present in these missives. Whereas vanity and egotism were unwelcome when people interacted in person, etiquette advisors suggested that in letters such egotism was acceptable. In 1857, Littell’s Living Age carried a feature on “Letter Writing and Letter Writers,” encouraging correspondents to write about themselves: “What but egotism should there be in a letter, if you care a fig for the writer? What other capital can be put out to such interest, if he interests you at all, as his own capital I?”

Despite such encouragement, some letter writers nevertheless worried that they were talking too much about themselves. Jenny MacNeven, visiting relatives in Washington, DC, wrote to her mother in New York City, describing her daily activities. In an 1840 letter, she wondered if she was dwelling overmuch on herself. She ruefully noted, “I suspect my organ of egotism (is there such an one?) will develop itself largely during my visit,” for she had already sent a three-page letter in the morning and was sending a second one later in the day to tell mother of her excursions and “all about myself.”

The same fear of dwelling too much upon the self struck Allen White, of Emporia, Kansas. While courting his future wife, he wrote to her of his genealogy. He then noted, “You did not ask me for my History but I concluded to volunteer trusting that you will not deem it improper or egotistical in me.” While he worried he might seem boastful and vain, he nevertheless regaled her with a description of his ancestors.

As nineteenth-century Americans mailed letters back and forth, exchanging missives filled with the details of their lives, they helped to inaugurate a new age of communication about the self. Often enclosed in the letters they sent were pictures. The earliest photograph, the daguerreotype, was created in 1839, in France. Brought to America’s attention by Samuel Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, daguerreotype studios quickly spread across the United States.

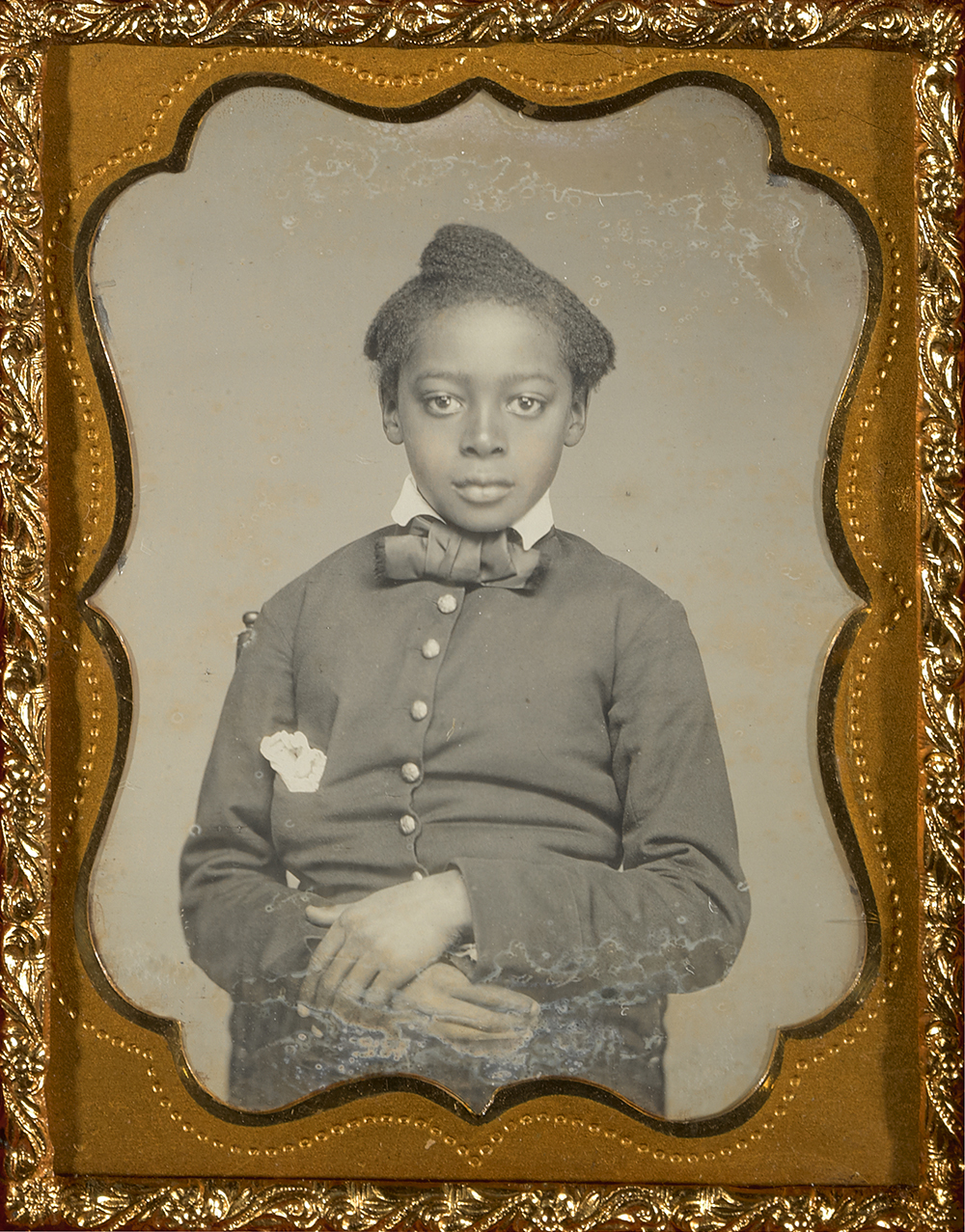

What was novel about the daguerreotype was that it democratized portraiture. Previously the ability to possess a likeness of oneself had been something only the wealthy enjoyed, for commissioning a painting was expensive business. Middle-class people, immigrants, workers, could not afford such an indulgence. However, very rapidly, photography became inexpensive enough that it was in reach of the many. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass celebrated daguerreotypes for enabling “the humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week” to have “a more perfect likeness of herself that noble ladies and even royalty…could purchase fifty years ago.” Whites, free blacks, poor, rich could now possess portraits of themselves.

According to the estimates of scholar Robert Taft, there were two thousand daguerreotype studios by 1850 in America; by 1853 they had captured three million images of Americans, at a time when the nation’s population was twenty-three million. Photographers were in particular abundance in newly settled regions, such as California during the Gold Rush, for many who had migrated there were eager to document themselves and their lives for family back at home.

Marcus Aurelius Root, a prominent photographer of the nineteenth century, described the potential of his “heliographic art,” writing that the photographer should strive to capture “that expression which reveals the soul within that individuality which distinguishes this from all human beings beside.” To capture a true picture of the soul, the photographer must create an environment in his studio that set his patrons at ease. Another photographer suggested drugging subjects in order to make them look natural, arguing that “a good dose” of laudanum “will effectively prevent the sitters from being conscious of themselves or the camera, or anything else. They become most delightfully tractable, and you can do anything with them under such circumstances.” However, he admitted, “the procedure entails a certain loss of animation.”

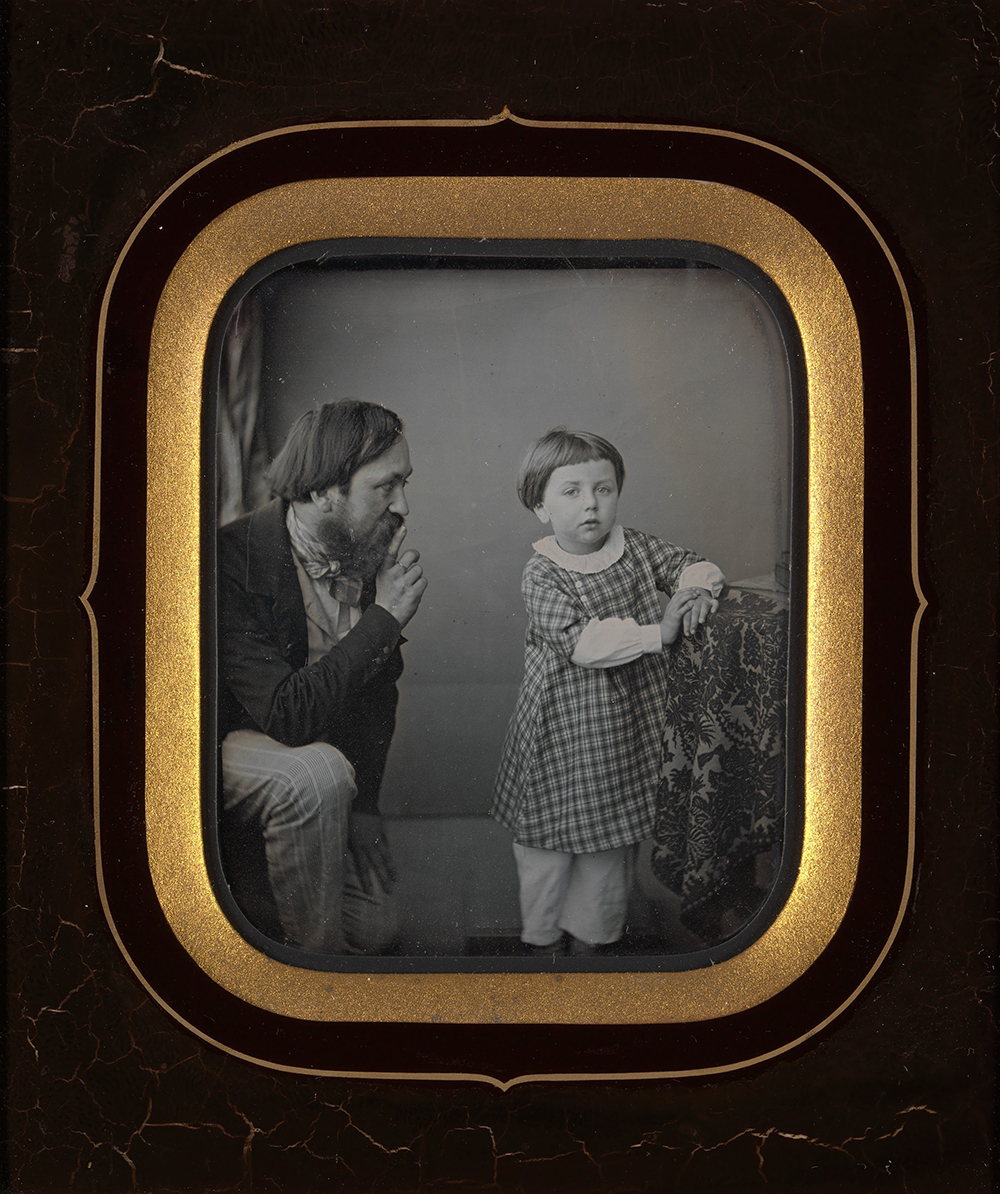

Yet while photos were supposed to produce authentic portraits of their subjects’ inner souls, photographers like Root also revealed the great care and attention they took to create such pictures. They offered advice on what types of clothing were most flattering to particular figures and what angles were best to offset facial and bodily imperfections. These were studied images they produced, and while many claimed photos could reveal the inner soul, they also stood as testament to the great effort individuals went to in order to cultivate particular selves.

For instance, an analysis of gold miners’ daguerreotypes revealed that even before they had headed west, many young men had their photos taken with all the imagined trappings of California life. James Ryder, a daguerreotypist whose studio was in Cleveland, Ohio, reported on the eager young men who trooped in for a picture: “Many who came for likenesses brought with them outfits to be shown in their pictures…[such as] tents, blankets, frying pans in which to cook bear meat, buffalo steaks, and smaller game by the way, and to wash out their gold on reaching the diggings.” These early photographs recorded aspirations and fantasies more than current realities.

Some worked at crafting their images in other ways, hoping to hide flaws or to present themselves in ways that differed markedly from reality. Photographers testified to the fact that many of their subjects were obsessed by their portrayals in a rather disturbing way. The mid-century moralist T.S. Arthur described “a stout, fat lady who would like to be made a little smaller” in her photo, and a “lean one” who “desires full handsome bust and round plump arms, as she is just now rather ‘thinner than common.’ ” There was much a photographer could do: “In fact, nearly all peculiarities of person that tend towards deformity may be modified by a skillful artist in the arrangement of his sitter—though he cannot help cross-eyes nor make a homely person beautiful.”

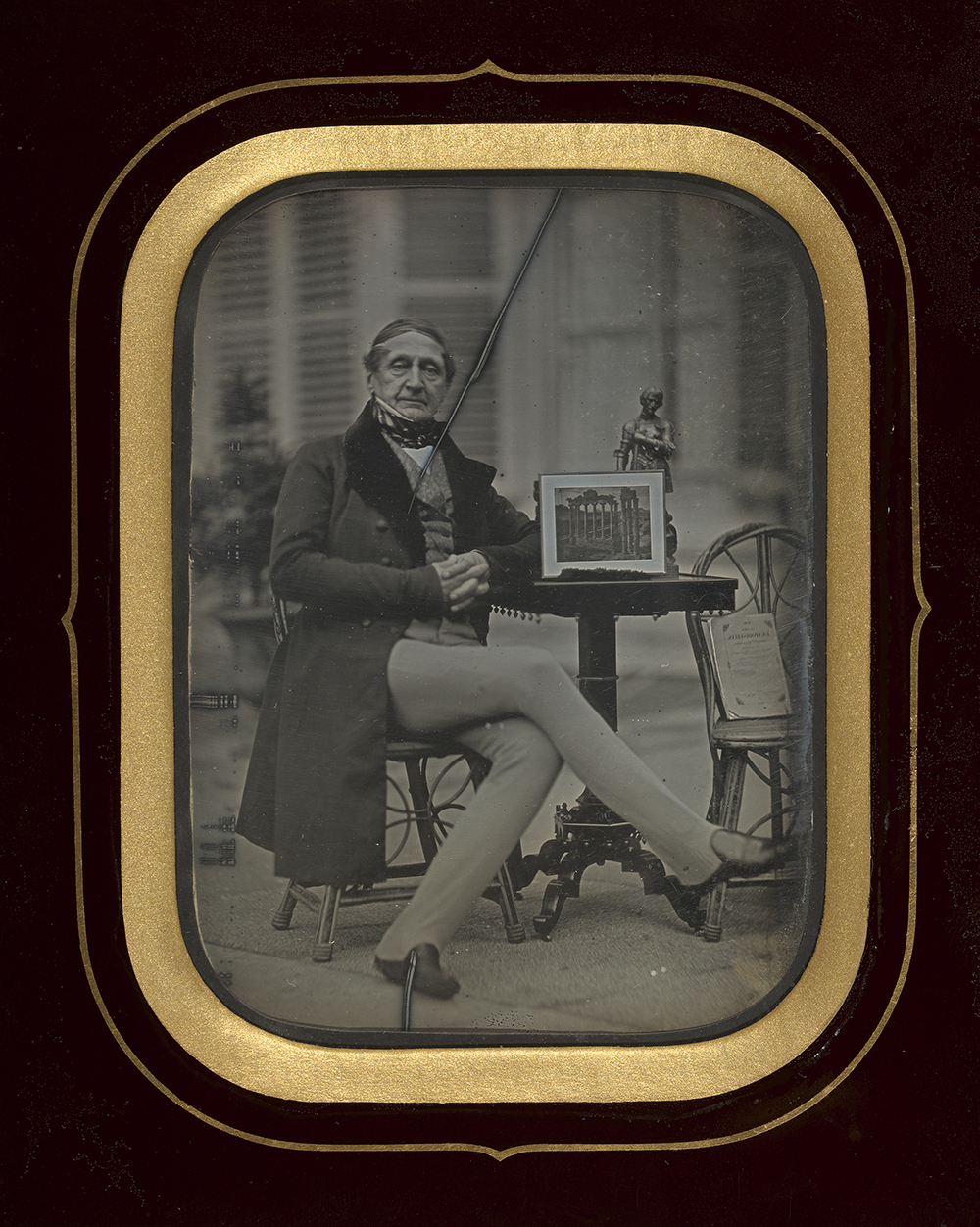

Another magazine pointed out the foibles of many portrait sitters who worked to cultivate pretentious and not always accurate poses and images. In an age when literacy was not universal, the ability to read was a mark of status that some were eager to display in their portraits. Subjects sometimes were therefore disposed to a “literary weakness. Persons afflicted with this mania are usually taken with a pile of books around them—or with the forefinger gracefully interposed between the leaves of a half-closed volume, as if they consented to the interruption of their studies solely to gratify posterity with a view of their scholarlike countenances—or in a student’s cap and morning robe, with the head resting on the hand, profoundly meditating on—nothing.” A young lady, for instance, who showed little interest in books, nevertheless “appear[ed] in her daguerreotype to be intensely absorbed in the perusal of a large octavo. What renders the phenomenon the more remarkable is that the book was upside down.” Others displayed a “musical weakness which forces a great variety of suffering, inoffensive flutes, guitars, and pianos to be brought forward in the company of their cruel and persecuting masters and mistresses.” The author reported that one woman, who was tone-deaf, nevertheless insisted on posing with “a sheet of Beethoven’s most difficult compositions, in her delicate dexter hand. Some amusing caricatures are produced by those who attempt to assume a look which they have not.”

Women were not the only ones with pretensions, however. “Timid men, at the critical juncture, summon up a look of stern fierceness, and savage natures borrow an expression of gentle meekness. People appear dignified, haughty, mild, condescending, humorous, and grave in their daguerreotypes who manifestly never appeared so anywhere else.”

Other photographers provided a wider array of props to their clients, in order to help them create attractive, if misleading, images of themselves. Indeed, some photographers made it part of their service to provide their clients with clothing appropriate for portraits, as the early African American daguerreotypist Augustus Washington did in his Hartford, Connecticut, studio in the 1850s. Others offered even more finery and luxurious accoutrements to patrons of modest incomes so that they could appear affluent in their portraits. A photographer whose studio was in a poor neighborhood explained his booming business: “It is because I throw in the clothes with the picture that I get along…You can come in here, for instance, in the dress of a tramp, and I will photograph you in the dress of a millionaire.” In doing so, he believed he was bringing joy to his clients and to those who viewed their deceptive images. He asked the interviewer to imagine he was a “young immigrant girl, and as yet you are not prospering here, for you don’t yet know the language. But to the old folks in the home country, in order to cheer them up, you write that you are doing wonderfully well.”

Excerpted from Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid: Changing Feelings about Technology, from the Telegraph to Twitter by Luke Fernandez and Susan J. Matt, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.