Small covered winepot or teapot, c. 1662. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975.

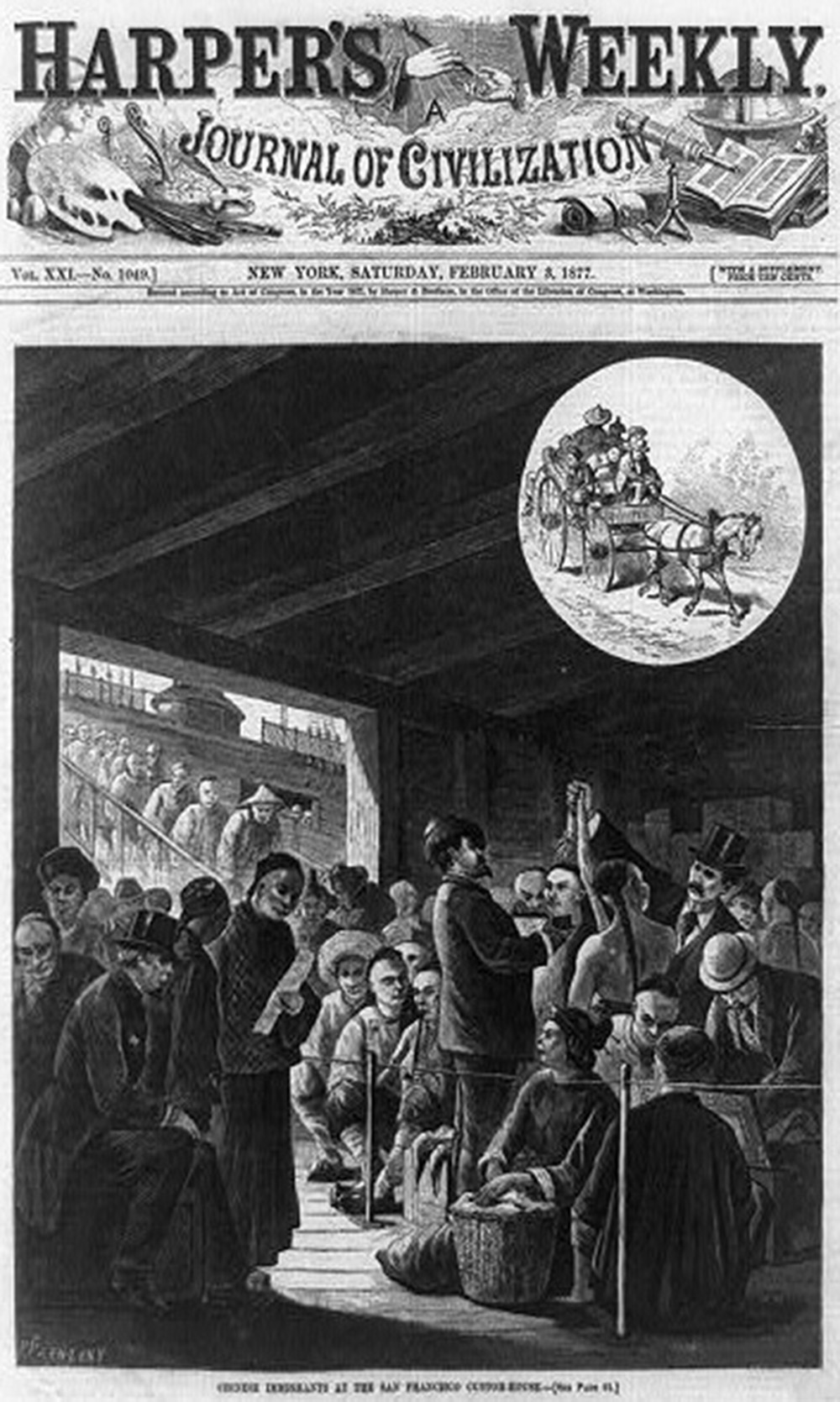

In the nineteenth century white employers imagined that Chinese immigrants to California had an innate, racial disposition to servility. This assumption overlooked how these laborers were actively shunted into areas of the economy where service work predominated. Chinese laborers were driven from occupations that white men claimed as their racial and gender birthright. Opposition to male Chinese servants emerged more gradually and only when the economic depression of the late 1870s made white women’s wages more essential both in California and across the country. The praise that American commentators heaped on Chinese servants alluded to the ingrained and inherited aptitude that the Chinese had for deferring to social superiors. These accounts misinterpreted the relegation of Chinese men to service jobs as a natural rather than political division of labor.

While historian Karen Leong is correct to note that anti-Chinese discourse insisted that “without a home, a ‘Chinaman’ had no reason to defend the country; without a family, a ‘Chinaman’ had no reason to invest in the future well-being of the nation; without a wife, a ‘Chinaman’ was simply barbaric and uncivilized,” this framing neglects the plastic and opportunistic agenda of capital. Employers of Chinese servants did not see their “sojourner” status as a dangerous quality. Because Chinese immigrants were marked as nonsettlers, servants were more easily detached from the competing dependencies and bonds that might otherwise demand their loyalties and labor. Unlike single white women who were constantly leaving service to assume unpaid domestic labor as married women in their own homes, a Chinese bachelor—often a misnomer, since many immigrants had wives in China—could be counted on to stay in a situation for a longer period of time. Chinese men did not pose the same liability therefore when it came to time spent hiring and training. Given employers’ frequent complaints that white female servants appropriated their fashion, it is unsurprising that Chinese men were celebrated as additions to the household who eliminated this particular concern. As one Californian employer observed, the male Chinese servant would “not outshine his mistress in attire.” Domestic advice author Harriet Spofford praised Chinese veterans of railroad work for being “strong enough to carry a weight of four hundred pounds among difficult mountain passes for twenty days together.” She added that this was the type of “strength” that mistresses did not have to “be afraid of overworking.”

The exploitation of Chinese men was also framed by the 1875 congressional passage of the Page Act, which restricted almost entirely the immigration of Chinese women to the United States. The Page Act required Chinese women to obtain visas from American consular officials stationed in Hong Kong and other ports prior to emigrating. (Officials were also authorized to prohibit the emigration of Chinese men to the United States who they determined were not “free and voluntary” labor.) Consular officials were predisposed to judging all single Chinese women as likely to work in prostitution upon their arrival in the United States. Historian Adam McKeown disputes whether or not the Page Act had any dramatic impact on the gender ratio of Chinese immigrants arriving in the United States, since men were expected to leave China on their own and then return with their earnings. Even if this is accurate, the role that the law played in shaping white Americans’ perception of Chinese men as tireless workers unconcerned with family should not be dismissed either. In Henry Grimm’s 1879 anti-Chinese immigrant drama The Chinese Must Go, for instance, a Chinese servant remarks that white men were “damn fools” for having wives and children who “cost plenty money.”

Some commentators claimed that Chinese men’s successful employment as servants proved that biologically they belonged to a “third sex,” and were devoid of typically masculine sexual desires. “Young ladies who have grown up with Chinese servants in the house all their lives,” an author claimed in the Quaker Friend’s Review, “tell me they never regard ‘John’ as a man.” Arguments of this sort helped white women justify allowing Chinese domestics’ access to their bedrooms and other spaces where the presence of men not their husbands was considered indecent. Accusations concerning male Chinese servants’ predatory lust, however, also circulated. In an 1876 article in Scribner’s Monthly, for example, Sarah Henshaw noted, “No matter how good a Chinaman may be, ladies never leave their children with them, especially little girls.” As a cartoon from the nativist publication Thistleton’s Jolly Giant illustrates, Chinese bodies were also depicted as sinister presences in domestic spaces. In “Innocent John,” the apparent asexuality of the Chinese servant is a ruse that allows him intimate access to white women’s bodies. Contradictory positions on Chinese sexuality coexisted. Chinese men working in domestic service were both modern-day eunuchs, unfit for independent manhood and queerly content to perform women’s work, yet also lascivious agents of sexual violence and miscegenation.

In order to explain why Chinese immigrants were specifically suited to domestic labor, employers traded in cultural and racial explanations that took them further away from the structural reasons close at hand. They depicted Chinese workers as mechanical in their efficiency and unimpeachably devoted to saving money for the households that employed them. Chinese servants, Spofford claimed, were, people of simple habits, content with simple diet, people with so few wants that small wages answer their purpose, people so bred in servility that they will not fail in respect, people accustomed to scrupulous economy and untiring labor, people of kindly manners and gentle dispositions, people trained, as it has been said, by forty centuries of manual dexterity—people of that description are exactly what it appears to her would fill the aching void in the American kitchen.

Spofford’s description of Chinese immigrants’ competencies as servants was rooted in her simplistic reading of Chinese history. Lacking a tradition of democracy and self-governance, she argued, the Chinese masses could be expected to remain serfs to whomever employed them, even when granted individual liberties.

In this vein, one of the most frequent explanations used to characterize what made Chinese immigrants superior servants was their talent for imitation. Restrictionists maintained that the rote fashion in which Chinese laborers performed work made them machines, and, like their inanimate iron counterparts, they were a comparable threat to alienate white laborers from wage-earning jobs. Employers, however, argued that Chinese servants’ aptitude for imitation carried special merit in the context of domestic work, where methods of cleaning and washing, not to mention cooking, left ample room for destructive improvisation. Before vacuum cleaners, dishwashers, and other household appliances were heralded as helping to routinize domestic work and wrest these tasks from careless servants, Chinese laborers were touted as purportedly allowing for the same type of standardization. The idea that the Chinese servant was a mirror, who reflected both the positive and negative traits of the individual who instructed him, led to dramatizations of the dangers of contaminating the “good” Chinese through negative influences. In the domestic advice literature of the period, authors advanced the notion that the Chinese servant, like a machine, still needed a thoughtful “operator.” A story in Scribner’s Monthly, for instance, presented a series of disastrous consequences that followed an employer’s decision to assign Kitty, the reigning Irish servant in her East Coast home, with the task of training Fing Wing, a Chinese immigrant newly arrived from California. When Fing Wing is caught stealing sugar and tea from his employers, he explains that he has learned this behavior from Kitty’s example. The illustration accompanying the article shows a similar theme. Fing Wing faithfully follows the lead of Kitty as she carelessly (or perhaps maliciously) lets fall a tray of plates and bowls. Employers were warned that “when you catch this Celestial domestic treasure, be sure that the first culinary operations performed for his instruction are correctly manipulated, for his imitativeness is of a cast-iron rigidity.” “Burn your toast or your pudding,” the author explained, “and he is apt to regard the accident as the rule.” An article in the New York Post relayed the story of an employer who was forced to dismiss her Chinese servant because he was too frugal. So closely did he police the amount of butter and bread that the family used after being instructed to do so, they could no longer stomach the shame his continual reprimands inspired.

The Chinese community in the United States contributed to how the Chinese servant’s racial identity was constructed, by invoking stereotypes about Chinese industry that aligned with the praises of white employers. It is not surprising that Chinese immigrants, denied allies in the white trade unions, turned to capital for assistance instead. Chinese immigrants singled out white workers and European immigrants in particular and accused them of being lazy. White workers, they argued, were privileged and protected by their race. Lee Chew, a Chinese cook interviewed by the Independent in 1903, stated that, were it not for racial solidarity, “no one would hire an Irishman, German, Englishman or Italian when he could get a Chinese, because our countrymen are so much more honest, industrious, steady, sober and painstaking.” In his opinion, “Chinese were persecuted, not for their vices, but for their virtues.”

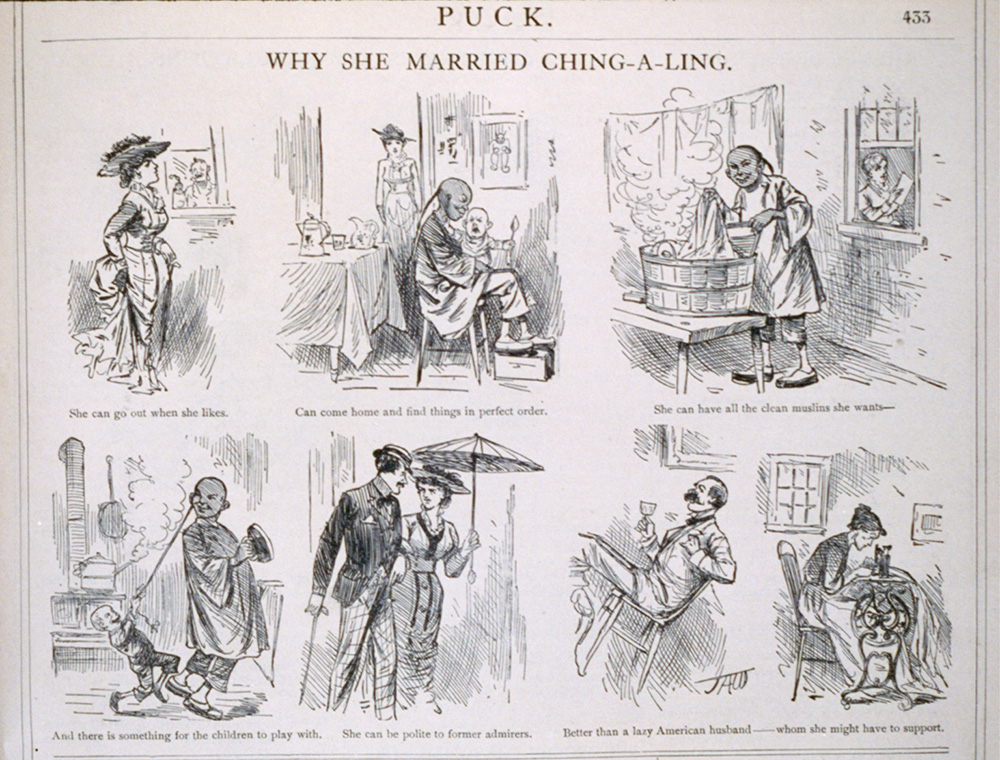

This view was echoed in the middle-class media, which used Chinese men’s perceived domestic utility to chastise the idleness of working-class white men depicted as having failed in their duties as heads of household. The August 1, 1881, issue of Puck magazine featured a cartoon titled “Why She Married Ching-A-Ling.” In it, a Chinese man, “Ching- A-Ling,” performs various domestic tasks in the different panels, his queue, robe, and slippers calling attention to his foreign characteristics. He serves tea and cradles an infant in his arm; he launders muslins; he irons while a small boy “plays” by pulling at his hair. As he labors, his white wife is shown profiting from the surplus value that his industry produces: time for leisure. As a caption explains, “She can go out when she likes.” Another frame shows her arm in arm with a white suitor, with the caption: “She can be polite to former admirers.” Wales’ final panel introduces an alternative yet at the same time more conceivable vision for readers to consider. The same woman is shown as haggard, disheveled, and bent over a sewing machine. Her white husband reclines in a chair, sipping a drink. The caption to the final frame, referring back to the imagined union with “Ching-A-Ling,” reads: “Better than a lazy American husband—whom she might have to support.”

Whatever the cartoonist J.A. Wales felt about the willingness of Chinese men to perform jobs marked as “women’s work,” his more immediate target was to call out working-class white men as breadwinners. The final frame of the cartoon insinuates that drunkenness, idleness, and the willful exploitation of loved ones plagued men of this class, and doomed their wives to working a second shift on top of their unpaid labor. The woman sews a dress, which it can be assumed has been subcontracted to her through the putting-out system, her home transformed into a factory. Although Wales was surely aware that his suggestion that white women might prefer Chinese men as husbands could be construed as inflammatory, his argument for interracial relationships is sarcastically conveyed as a matter of convenience rather than desire. The woman uses the relationship merely to preserve a more carefree social life; the children pictured do not have the visual cues of being the products of “miscegenation.” Wales’ take is quite different from those that could be found in images from the antebellum period, which focused on interracial couplings between Irish immigrant women and Chinese men in New York’s Five Points neighborhood, but to highlight local “exoticism.” In the Puck caricature, Wales is less concerned with taboo and more bent on offering a humorous yet cautionary take on how Chinese men might factor into American households’ economy if white men could not prove themselves to be more responsible.

Adapted from Brokering Servitude: Migration and the Politics of Domestic Labor During the Long Nineteenth Century by Andrew Urban, with permission from New York University Press. Copyright © 2017 by New York University Press.