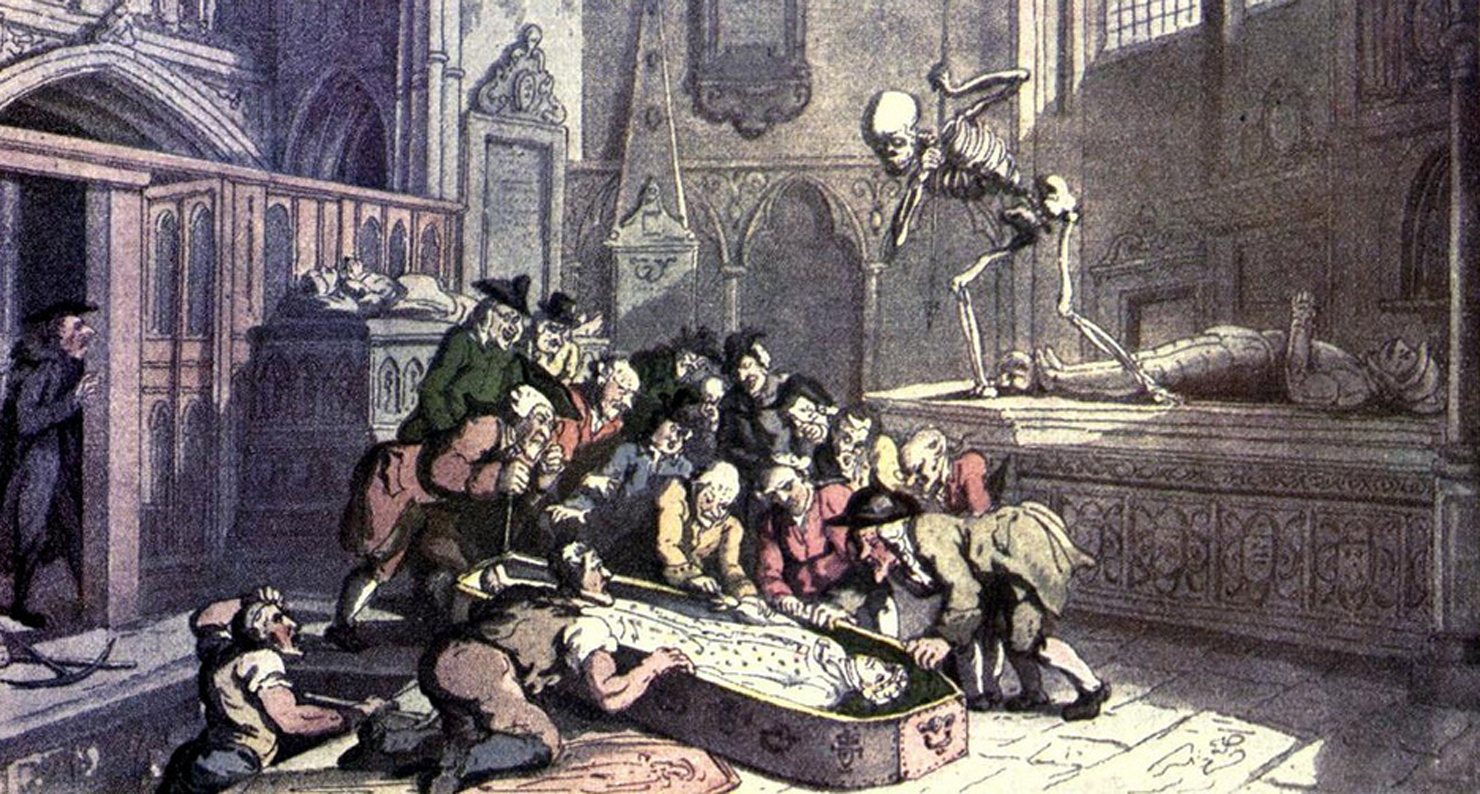

Death and the Antiquaries, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1816.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

There was a lot to be afraid of in New York after the Revolutionary War. Burned buildings loomed out of dark, crooked streets, which met at strange angles. Fights broke out in the taverns, while thieves lurked in the shadows. Families huddled in shantytowns constructed out of ships’ canvasses, while garbage piled high on the corners. The city watch was nothing more than forty men with clubs.

Besides the thieves and the brawls, people feared the medical students. The young men in black suits who studied at Columbia College and New York Hospital did as their teachers from England and Scotland had done: they learned anatomy by dissecting bodies stolen from the local cemeteries. In London and Edinburgh, a quasi-professional class of grave-robbers known as the “Resurrection Men” dug fresh corpses from the cemeteries of the poor and brought them to the medical school. In eighteenth-century New York, the medical students robbed the graves themselves, sneaking into cemeteries on cold, moonless nights and carrying wooden shovels to avoid the loud scrape of metal on stone.

But the bodies on the dissecting tables in New York often had a different hue than the bodies in Europe. African-born slaves had been in New York since 1626, when the Dutch imported eleven men from Central and Southern Africa to construct the earliest buildings of the settlement. In the years that followed, the city’s population of Africans—from Congo, Ghana, Ashanti, Benin, and other states—swelled with slaves imported to farm the fields. The English continued the trade, and by the mid-eighteenth century enslaved Africans were unloading cargo at the docks, piloting boats carrying produce from Long Island, building ships, and constructing and repairing the city streets. At the start of the Revolution, New York had more enslaved Africans than any English colonial settlement except Charleston, South Carolina. By the end of the Revolution, about a fifth of the city’s population was of African descent.

When the slaves of New York died, usually of disease and overwork, they were buried in an unincorporated patch of land in a wooded ravine just north of Chambers Street, near the Collect Pond. The city’s fathers had declared the churchyards—the favored burial spots of the elites—off-limits to blacks both free and enslaved. Just as there was a hierarchy for the living in New York, there was a hierarchy for the dead. Although it was illegal for the city’s slaves to congregate at night, they did so for funerals, wrapping their dead in shrouds and lowering the bodies into coffins always buried with the heads facing west, so the faces would be pointing east when they arose in the afterlife.

Often the bodies didn’t stay buried for long. While the wealthy could purchase iron cages and all-night guards to keep the dead safe from the medical students, slaves didn’t have those resources. And the medical students from Columbia and New York Hospital only had to walk a couple of muddy blocks to reach the African burial ground, as well as the potter’s field just next to it. There’s every reason to think the graverobbing was an open secret around early New York, known and tolerated by elites who justified the growing anatomical expertise in the new nation produced—just like much of the rest of the early city was produced—on the backs of blacks.

Not that black New Yorkers didn’t protest. On February 14, 1788, a group of free and enslaved blacks submitted a petition to the Common Council:

Most humbly sirs, we declare that it has lately been the practice of a number of young gentlemen in this city who call themselves students of the physic, to repair to the burying ground, assigned for the use of your petitioners. Under cover of the night, in the most wanton sallies of excess, they dig up bodies of our deceased friends and relatives of your petitioners, carrying them away without respect for age or sex. The petitioners “would not be adverse” to such dissection, they wrote, “if it is conducted with the decency and propriety which the solemnity of such occasion requires.”

But the petition was ignored. So was a letter in the Daily Advertiser about two weeks later which complained “that few blacks are buried, whose bodies are permitted to remain in the grave.” But on February 21, 1788, the Daily Advertiser printed an announcement saying that a body had been stolen from Trinity Churchyard. With that, the elite of the city found themselves in the same position as the blacks and poor whites. An invisible, but glaring, line had been crossed.

No one is sure how the new nation’s first riot began. One popular story has it that on April 13, 1788, several boys were playing in a grassy area outside New York Hospital, where a student named John Hicks was dissecting an arm. Hicks, who was probably no more than sixteen or seventeen, is said to have waved the arm out the third-floor window at one of the boys, yelling, “This is your mother’s arm! I just dug it up!” The boy’s mother had in fact recently died, and he ran down Broadway to tell the story to his father, a mason. The man exhumed his wife’s coffin, and after finding it empty, marched on the hospital with a group of angry worker friends still carrying their tools.

Colonel William Heth, writing in a letter to Governor of Virginia Edmund Randolph, described what happened when the workmen got to the hospital:

The cry of barbarity and etc. was soon spread—the young sons of Galen fled in every direction—one took refuge in a chimney—the mob raised—and the Hospital apartments were ransacked. In the Anatomy room, were found three fresh bodies—one, boiling in a kettle, and two others cutting up—with certain parts of the two sex's hanging up in a most brutal position. The circumstances, together with the wanton and apparent inhuman complexion of the room, exasperated the Mob beyond all bounds, to the total destruction of every anatomy in the hospital.

The workmen hauled bones and half-dissected bodies from the anatomy rooms into a heap on the street, and set them ablaze in a giant bonfire. Although most of the doctors and medical students had already fled, those who remained to guard the valuable collection of anatomical specimens were also dragged out into the streets. They might have been added to the bonfire too if it hadn’t been for the arrival of Mayor James Duane, the sheriff, and several others, who carried the medical men off to jail for their own safety.

The following day, hundreds of angry men ran around the city looking for doctors, medical students, and bodies. A mob surged on Columbia, despite the efforts of alumnus Alexander Hamilton, who stood on the school’s front steps to try and defend it. But the men pushed past, broke into Columbia, and searched the museum, chapel, library, anatomical theatre, and even student’s bedrooms for bodies and bones. Finding nothing (savvy students had removed all the specimens the previous night), the men marched down Broadway to the jail. Governor George Clinton, mayor Duane, and other prominent political men urged them to disperse, but they refused, and as day turned into night, the crowd swelled into the thousands. Armed with rocks and clubs, the mob descended on the jail and began tearing it apart. Clinton called out the militia, who opened fire and charged with bayonets; at least three rioters and three members of the militia were killed. The militia patrolled the streets for days until things settled down, but the reputation of doctors in New York was blighted for years.

The following year the New York Legislature passed the first law sanctioning dissection in the United States. The law—“An Act to Prevent the Odious Practice of Digging Up and Removing for the Purpose of Dissection, Dead Bodies Interred in Cemeteries or Burial Places”—outlawed grave-robbing and provided that criminals executed for murder, arson, or burglary could be sentenced to dissection after death. But the law wasn’t effective: there weren’t nearly enough bodies of executed criminals to satisfy the demand for cadavers in New York, and so the medical students continued to rob graves, although they were forced to be much more discreet. Evidence suggests that grave-robbing continued into the nineteenth century, and when there weren’t enough bodies in the North, dead slaves were sent from the South packed in barrels of whisky.

In May 1991, archeologists hired by the General Services Administration to examine the ground beneath a planned federal office building at in lower Manhattan struck bone. And then more bones, and more bones. Historians knew that the place they were digging, just north of Chambers Street, was marked on old maps as the “Negroes Burial Ground.” But they also knew the ground had been closed to new burials at the end of the eighteenth century, and records showed that portions of the area were paved over soon after that. The GSA expected the graves to be long gone, but landfill in the early nineteenth century had protected many of the remains. The archeologists found rotting wooden coffins, and then hundreds of skeletons in the ground, many virtually intact.

The discovery revealed the city to itself, bringing to light a particularly painful chapter of its past and combating the common misperception of New York as a place free of slavery. Although the GSA initially planned to exhume the bodies and continue construction, a passionate group of politicians and activists calling themselves the “Descendent Community” demanded otherwise. The agency suspended construction and revised their blueprints to allow for a monument and visitors center over part of the burial ground, even as a gleaming tower was constructed elsewhere on the site. After much debate, the remains unearthed there were sent to the historically black Howard University in Washington, DC, for study. Years later, researchers produced a report showing that the bones—419 skeletons in all—showed not only occasional signs of dissection, but thickened ridges, stiffened joints, bone degeneration, and other results of heavy labor. The researchers also estimate that between ten and twenty-thousand early black New Yorkers are still buried in the area today roughly bounded by Broadway, Duane, Centre, and Chambers Street, hidden beneath the gleaming office buildings and sandwich shops.

Today the site is a national monument, where visitors can walk through a deep circle carved with symbols from the African diaspora, and visit a black marble chamber designed to be reminiscent of a ships’ hold. The chamber is twenty-four feet high, as high as the remains were discovered deep beneath the earth. Seven grassy mounds cover crypts containing the 419 bodies, ceremonially reburied after a six-day ceremony in October of 2003. On a recent visit, the mounds were strewn with roses, and a park attendant said that someone makes sure the flowers are always there. In the visitors’ center, groups of schoolchildren posed for photos in front of images of the remains. Meanwhile, the city’s medical students have moved north, and most don’t know that the history of their profession in this city is indebted to this long-hidden graveyard.