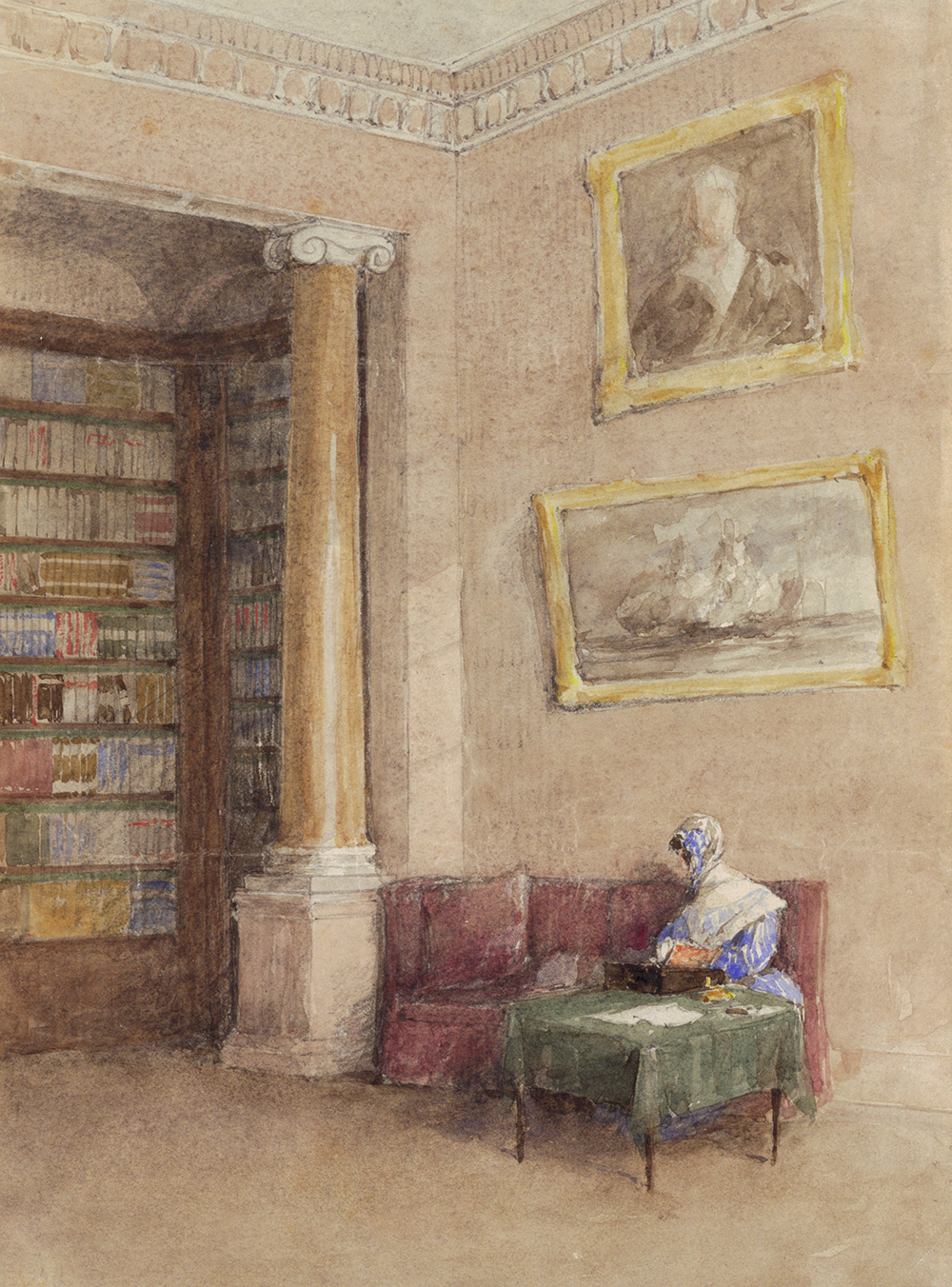

Page from Scribner’s Magazine, March 1905. Illustration by David Ericson. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.

For all her successes, Edith Wharton made a habit of spurning the conditions of her own fortune. She became the first female novelist to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1921—for The Age of Innocence—only to wind up mocking the prize less than a decade later. In her novel Hudson River Bracketed (1928), she describes the thinly veiled “Pulsifer Prize” as a sham, the product of a “half-confessed background of wire-pulling and influencing.” By the time she was honored again by the Pulitzer committee—this time by proxy, for playwright Zoe Akins’ 1935 adaptation of one of her novellas, The Old Maid—Wharton had distanced herself from the prize and its milieu.

Her relationship with motion pictures was similarly detached, even as she received consistent financial benefit from the industry throughout the final decades of her life. In a 1926 letter to a friend, she comments, “I have always thought ‘The Age’ would make a splendid film”—which it did many years later, in 1993, in the hands of Martin Scorsese. But before that, it was made into a silent film by Warner Brothers in the 1920s, along with many of her other novels. Wharton’s sale of film rights to her 1928 novel The Children fetched her $25,000 (more than $350,000 in today’s dollars). She used the money to help maintain multiple French residences, even as she declined to enter a movie theater during her lifetime. Indeed, she remained totally uninterested in films, even those based on stories she had invented.

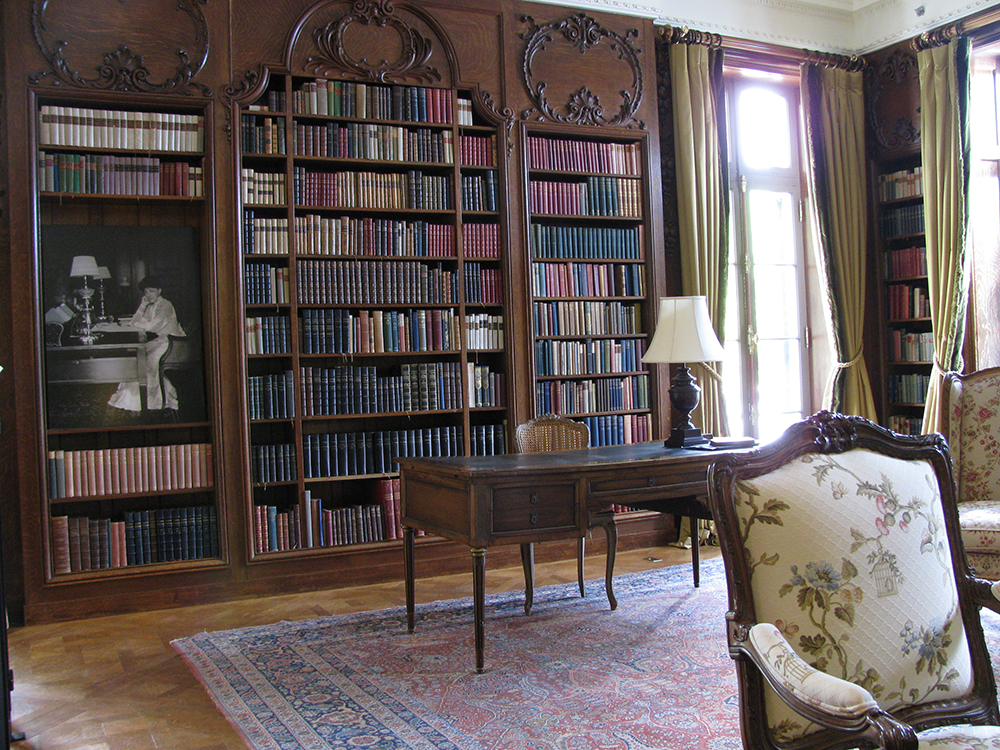

As a best-selling author, Wharton was aware of society’s tendency to view success and quality as being diametrically opposed. And as a reader, she enacted some of that distrust, opting for classic titles that had been vetted by previous generations over the best sellers of her day. We know this from her library, which is currently housed at the Mount estate in Lenox, Massachusetts, the custom-designed home where she and her husband, Teddy, lived and spent their summers in the early 1900s. After traveling the globe following her death in 1937, Wharton’s books—or at least the 2,700 of them that remain—came home to the Mount in 2006, after being sold by a British collector who had reassembled her library. These books have much to say about the person who was Edith Wharton, but particularly about the reader behind the enormously successful author who was Edith Wharton. They show us her wide-ranging and seemingly paradoxical interests in subjects like evolutionary science, religious history, and pragmatist philosophy—but so too do they reveal omissions she elected as a reader.

One of those omissions concerns successful works of fiction that weren’t her own. Even with her reputation as a popular novelist, Wharton couldn’t be induced to read most of the other best sellers of her day. Take, for instance, her relationship with Owen Wister, author of The Virginian. The novel was a best seller in 1902, the year it was first published, and again the following year, when it finished at number four on the Publishers Weekly best-seller list. Wharton was friendly with Wister; they were close in age, and he had been known to frequent the outer edges of her social circle in Lenox. Upon reading her 1905 best seller The House of Mirth, Wister wrote to her, proclaiming it “un ouvrage parfaitement distingué ”—a perfectly distinguished work—one that had “set the world discussing.” Yet today Wharton’s library contains no works by Wister, not even a copy of The Virginian.

This doesn’t mean the book never graced her shelves; there are other possible explanations for its absence. Prior to her death, Wharton willed the contents of her library to two young men she barely knew. Never having had children of her own, she regarded Colin Clark and William Royall Tyler—both sons of friends of hers—as worthy heirs and proceeded to divide the books among them. Tyler received much of the fiction volumes, which he went on to store at a London warehouse that was destroyed by a German bomber during the London Blitz in 1941. What it contained is anyone’s guess; Tyler never got around to having it catalogued or itemized. Perhaps Wister’s books were included.

But, then again, perhaps not. Probably not, in fact, since privately Wharton had dismissed Wister’s writing as “flippant.” In a 1907 letter to her friend Sally Norton, she admits as much while complaining that (thanks in part to writers like Wister) “flippancy is the only tone in which a serious subject of any kind may be made interesting to our public.” The suggestion is that popular writers view levity as a way to appear likable to their readers. And Wharton, with her catalogue of difficult literary heroines, didn’t want to be liked: she wanted, if anything, to expose the corrosive qualities of likability and illuminate the secret, lurking cruelty behind it. To be liked, her novels collectively seem to say, is to be unimportant.

That is because in order to like something, one generally has to be familiar with it. Audiences like not what shocks or disturbs them but that which flatters their experience and appears to validate what they already know. This at least is the critic Gordon Hutner’s point in his book What America Read (2009), which surveys the age of best sellers in which Wharton was reared. Hutner observes how the best sellers that defined Wharton’s day were generally characterized by accessibility; we’re talking about the western writer Zane Grey, in other words, not Ulysses. The former’s name appears repeatedly on best-seller lists dating from the late 1910s and 1920s, while the latter was released in a limited thousand-volume print run in 1922 following a censorship battle. Wharton had no love for James Joyce’s masterwork, but that didn’t stop her from owning a copy of it, which can be found today in her library at the Mount. To own such a work was tantamount to choosing a side where the cult of the ever-likable best seller was concerned. It was an issue of principle, not personal taste.

Read more about Prizewinning Top Sellers

As her own novels continued to top sales lists throughout the 1920s, resulting in what some critics regarded as a decreasing standard of quality, Wharton doubled down on her readerly affiliations, siding with folks like Joyce even as her proceeds kept her tethered to folks like Grey. In 1921 sales of The Age of Innocence placed her just below Grey, whose The Mysterious Rider ranked third overall that year. When Wharton subsequently learned she had won the Pulitzer for that work, she dedicated the novel to Sinclair Lewis, one of the few best-selling compatriots of hers whose writing she actually deemed worthy. The Pulitzer Prize was still new at this point, having debuted only four years earlier, in 1917, and Wharton sensed that it had not yet begun to assert “standards” or to market itself as an arbiter of quality, as opposed to popular, taste. As she put it in a glowing letter to Lewis, “Some sort of standard is emerging from the welter of cant and sentimentality, and if two or three of us are gathered together, I believe we can still save fiction in America.” Wharton was marshaling her troops, entreating them to fight and die for a cause in which she herself might have been easily mistaken for the aggressor.

As with Lewis, Wharton made other occasional exceptions where best-selling authors were concerned. Among them was H.G. Wells, and here, too, Wharton and Lewis—who often bemoaned the quality of popular fiction in their letters to each other—were in agreement: Lewis christened his son Wells in honor of the popular science fiction writer, with whom both he and Wharton were friendly. Today one can find several of Wells’ novels in Wharton’s library, including his 1905 work Kipps, which, while it sold slowly upon publication, became one of his best-known and most admired works, selling a quarter of a million copies by 1920. There is also Frank Norris’ best-selling naturalist epic The Pit (1903), his sequel to The Octopus (1900); Wharton’s library retains a first-edition copy of the former, which is especially intriguing given the fact that it lacks the more popular latter.

Many of the authors who, like Wharton, achieved literary stardom between 1900 and 1930 are not well remembered now. Or else, like Zane Grey, their lingering fame is not based on estimations of literary merit. But some—like Booth Tarkington, Ellen Glasgow, Gene Stratton Porter, and Elizabeth von Arnim—continue to lay claim to certain portions of our collective cultural memory. So how can we account for their absence in Wharton’s library?

It is not enough to say that Wharton was simply a snob (though she likely was, and wouldn’t have bristled much at being called one, either). Rather, her educational breeding had taught her to extend her tastes and sympathies backward and to rank historical achievements over contemporary trends. For instance, a quick, quantitative survey of the publication dates of the books in her library reveals a period of intense acquisition: Wharton’s book buying spiked dramatically between 1909 and 1913. This occurred in the wake of The House of Mirth, her first big financial success, and in tandem with the publication of some of her other popular titles, like Ethan Frome (1911). Yet most of the books that she acquired during this period were older titles. Among them was a 1911 French-language edition of French writer George Sand’s novel Elle et Lui, originally published in 1859, and a 1911 reprint of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Journals, which date from the 1830s. Some of these she had read as a child, and she was looking to acquire better, updated editions as an adult, but many others were new to her. Wister had another hit in 1911 with the publication of Padre Ignacio, but Wharton, it appears, was too busy reading her way back into the nineteenth century to pick up a copy.

Wharton did not seek to divorce herself from contemporary literature. She kept up with it in her own discriminating way, devouring each volume of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu (1913) in hungry succession as it became available (she added enthusiastic annotations to her copies, with the exception of Sodom and Gomorrah, about which her pencil remained stonily silent), as well as reading the work of her close friends and correspondents. But she insisted on setting herself apart from the best-seller scene, which she saw as being driven by the ever-fragile whims of fashion. Like many other writers before her, she perceived fashion to be the enemy of forever. Wharton knew that most classic works of literature tend to fall under the category of the succès d’estime, or popular flops that nonetheless achieve critical praise and, eventually, inclusion in the literary canon. She knew it because those were the kinds of books she herself read and purchased, even as literary modernism appeared on the horizon, demanding that writers and artists “make it new!”

In books, as in most things, Wharton looked askance at “the new,” seeking inspiration instead from history. What’s interesting is how her efforts to do so bore fashionable, best-selling, and prize-winning fruit. The Age of Innocence takes place half a century before the time of its writing and features a heroine, the Countess Olenska, who proclaims, “I want to be free; I want to wipe out all the past.” But Wharton knew this was impossible. She built her whole novel around the idea of its very impossibility and today is still remembered for it.