Advertisement for the Trans-Siberian Railroad exhibit at the Universal Exposition in Paris, by Rafael de Ochoa y Madrazo and Lemercier, 1900. Digital Magazine of Railway History, Design, and Photography.

For many travelers, riding on the Trans-Siberian Railway is the trip of a lifetime—a journey narrated in novels, chronicled in travelogues, featured in films, and celebrated in songs. For others, the Trans-Siberian has been a railway to exile, to prison, or worse. But for many people the railway has been—and still is—merely the most convenient, least expensive, and sometimes only way to travel by land from one place to another across the vast distances of Russia.

Constructed between 1891 and 1916, the main Trans-Siberian route runs between Moscow, Russia’s capital, and Vladivostok, the country’s major port on the Pacific Ocean. Originally called the Great Siberian Railway, the rail line was built across southern Siberia between the Ural Mountains and the Russian Far East to link up with existing lines on the European side of Russia. Eventually the entire route between Moscow and Vladivostok came to be known in Russian as the Transsibirskaya Zheleznodorozhnaya Magistral (Trans-Siberian Railway Mainline), or the Trans-Siberian Railway in English. In Moscow the Trans-Siberian line connects with trains running between the capital and Russia’s second-largest city, St. Petersburg, on the Gulf of Finland—making it possible for passengers to travel the entire length of Russia by rail, a distance of nearly ten thousand kilometers (six thousand miles) across two continents, Europe and Asia.

Today the Trans-Siberian is still the longest continuous passenger railway on the globe. But, contrary to popular belief, there was never a single Russian train on that line named the Trans-Siberian Express. Although marketed in the West as the “Trans-Siberian Express,” it was actually a long-distance rail service with several passenger express trains crossing the entire route between Moscow and Vladivostok. By the 1930s three Trans-Siberian trains left both of those stations on alternate days each week, traveling in opposite directions—a schedule still in place today.

From the beginning, the Russian railway system has been a government-owned enterprise, although sometimes with private companies as investors or concessionaires. Depending on the time period—Tsarist, Soviet, post-Soviet—food service in the dining cars and railway station restaurants (“buffets”) was provided by the government or by concessionaires and franchisees. And from the start, freelance vendors on the station platforms have also sold a range of local and regional foods to passengers all along the route. During the initial phase of construction in the 1890s, when several sections of the tracks were not yet connected, there was passenger service on only some parts of the line and no dining cars on the trains. Travelers had to bring their own food in picnic baskets or eat at railway station buffets (usually at larger stations only), or buy homegrown, home-prepared foods from vendors on the station platforms.

Traveling in the 1890s, the Englishman Robert L. Jefferson described one of those early railway station buffets very vividly:

In we squeeze, and find ourselves in a long, whitewashed apartment, heated to a suffocating degree. Down the centre of the apartment runs a long table covered with glasses, plate, and cutlery. Over on one side is a long bar, covered with smaller glasses and large bottles, mostly containing vodki, as well as at least half a hundred dishes of the hors d’oeuvre style—sardines, bits of sausage, sprats, caviar, sliced cucumber, pickled mushrooms, artful dabs of cheese, raw radishes, smoked herring, and such like…[and] a kitchen-like arrangement in the corner where steams a heterogeneous mass of cutlets and Russian beef-steaks…Vodki is the lodestone of the arrived passengers. Each man gulps down a small glass of the fiery fluid, seizes a piece of fish or sausage, or cheese, or whatever he may fancy or may be handy, and subsides to the big table, chewing vigorously. Energetic waiters pounce upon him, lay before him a big plate of the universal “stche,” or cabbage soup, over which our Russian hangs his head and commences ladling away, apparently oblivious to its boiling heat or the feelings of people around him. The tables fill up. Great slabs of brown meat, floating in fat, are distributed with rapidity, and which with equal rapidity are demolished.

John W. Bookwalter, an American industrialist who traveled through part of Siberia in 1898, noted that at station restaurants:

You can get soup, as fine a beefsteak as you ever ate, a splendid roast chicken whole, cooked in Russian style, most toothsome and juicy, potatoes and other vegetables, a bottle of beer, splendid and brewed in this country, for one ruble—about fifty cents.

In the summer of 1900, Reverend Francis E. Clark traveled westward from Vladivostok to Moscow by rail and river, a journey that took thirty-eight days because of unexpected delays along the route. His first meal on the train was in one of the earliest Trans-Siberian dining cars, on the Ussuri Line between Vladivostok and Khabarovsk:

A long table down the middle, at which perhaps twenty people can sit at one time, and a bar at one end, at which all kinds of light and strong drinks are served, and toothsome delicacies dear to the Russian heart, like caviar, sardines, and other little fishes…At the long table table d’hôte meals are served, consisting of three or four courses, and one can also order what he chooses at a fixed price…though not luxurious…[the meals] are quite sufficient for the average traveller. To be sure, one must get used to the greasy Siberian soup and to the chunks of tough stewed meat, which may be beef, mutton, or pork, one is never certain which.

In the early 1900s, the Wagons-Lits company did operate a couple of so-called International trains in Russia, which were marketed in Europe as a “Trans-Siberian Express” service. Designed to attract foreign passengers on the Trans-Siberian route, those trains were more luxurious than standard Russian trains of the time. But since the company was not certain that the Trans-Siberian enterprise would be profitable, it initially did not run its best cars on the line.

An American who crossed Siberia several times on those International trains was still favorably impressed:

The food in the dining car was superb—an abundance of game, unlimited caviar which came from Lake Baikal en route, thick Siberian cream, rich sauces, brandy, good cigars.

In the early twentieth century, Tsar Nicholas II and his family traveled in their own elegantly furnished railway carriages, with their own private dining car and lounge car. But the First World War, the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, and the Russian Civil War that followed put an end to the era of luxury train travel in Russia. In the chaotic period between the start of the First World War in 1914 and end of the Civil War in 1922, more than 60 percent of the railway network, 80 percent of the carriages, and 90 percent of the locomotives were destroyed. Traffic volume on the Russian railway system did not reach its prewar level again until 1928.

After the Revolution, the Bolshevik government confiscated the Belgian Wagons-Lits company’s railway cars in Russia, including the dining cars. But in rebuilding the damaged railway system, the new Soviet government focused primarily on the military and industrial uses of the railway, at the expense of “bourgeois” passenger service, including food service. However, during the Soviet era the major Communist Party figures and top government officials had their own private railway cars, which were considerably better than those for ordinary travelers. High Soviet officials even rode on private trains with the best accommodations and food service in the country—mimicking their tsarist predecessors and predating the same practices by important government officials in the Russian Federation today.

Crossing Siberia by train in 1926, Junius B. Wood, European correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, observed that the previously well-maintained passenger cars were now very dilapidated, with cracked windows and torn carpets. The dining car food was also bad:

At 3:30 a plate of soup appeared—greasy hot water poured over cold pieces of fish which had been cooked earlier in bulk. The next course was precooked cauliflower warmed with a sauce of unknown texture. Roast veal, cooked weeks earlier and now dry and hard, smothered in warm brown gravy, without vegetables, was the main course. A compote of fruit completed the hurried meal. The price was 1.75 rubles. Drinking water, butter, or a napkin cost extra.

An American who rode on the Trans-Siberian and Trans-Manchurian routes from Moscow to Peking in 1935 remembered the dining car as “dismal” and recalled surviving the trip on vodka and apples purchased from the vendors on the station platforms.

Between the end of the Second World War in 1945 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, dining cars on most Soviet trains generally had a bad reputation. They seated forty-eight people at twelve tables or booths (six on each side of a center aisle), with a tiny galley located at one end staffed by a cook, one or two waitresses, and a busboy, who also washed the dishes. But few people chose to eat in the dining cars, because the food was usually poor, the staff were surly, and the prices were relatively high for the average Russian. Most travelers brought their own food to the train, or bought food from vendors on the station platforms along the way—as travelers had done ever since passenger service began on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Standard dining-car menus during the post–Second World War period were up to ten pages long and offered a wide range of dishes—appetizers, soups, main dishes, side dishes, and desserts—although usually only two or three of the listed dishes were actually available on the train. Meals commonly consisted of a piece of unspecified meat, often dubbed “mystery meat” by the passengers, accompanied by potatoes or another starch (rice, pasta), maybe a sauerkraut salad, and perhaps canned peas. In addition, the dining-car staff often ran a lucrative (and illegal) side business selling the train’s food supplies to locals at the stations where the train stopped; hence less food was left for serving in the dining car.

The British writer Eric Newby chronicled his 1977 Trans-Siberian journey across Russia in a popular travel book, The Big Red Train Ride. Shortly after he boarded the train in Moscow, a woman working in the galley brought to his cabin

cream in bottles, borscht, rice, and meat the color of the weather outside swimming in a sort of greasy bouillon, all of which she carried in nestling aluminum containers.

Having heard from previous travelers that the food on Russian trains was both poor in quality and high in price, Newby had brought several boxes of his own food supplies with him. His expectations of Russian railway cuisine were confirmed on his first foray to the dining car:

The food was as unappetizing as that being hawked up and down the train, and the kitchen was equally so…There was no beer or vodka on board, and the only wines on offer were Russian champagne…and what appeared to be some sort of dessert wine of a sinister brown color.

A new development after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was that foreign investors were allowed to operate private charter trains on Russian territory, reviving the standards (and nostalgia) of pre-Revolutionary luxury train travel there.

Founded in 1988, GW Travel (headquartered in England) began operating private chartered train tours in European Russia in 1992 and on the Trans-Siberian route in 1996. Initially the trains comprised several old Soviet/Russian vip cars, including dining cars, which the company leased from the Russian Federation government. These were higher-standard private cars that had previously been reserved only for top government and Communist Party officials and not used on regular trains. Some of the train carriages even dated back to 1914. Travelers on those refurbished luxury railway cars were probably unaware they that were drinking champagne and eating caviar in the same carriages formerly used by some of Russia’s most notorious political figures of the twentieth century.

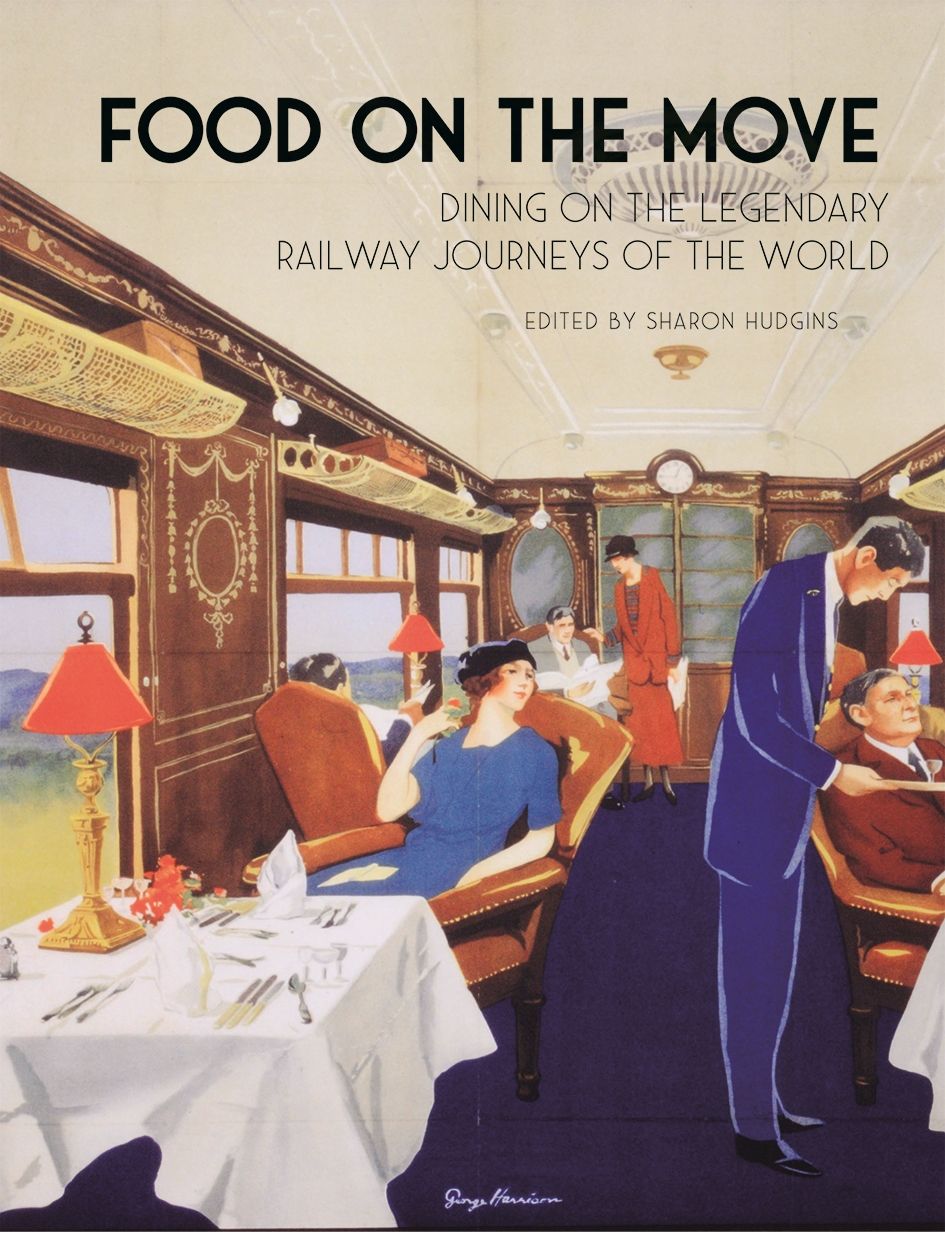

Excerpted from “From Caviar to Mystery Meat: Dining Across Two Continents on the Trans-Siberian Railway” by Sharon Hudgins, an essay from Food on the Move: Dining on the Legendary Railway Journeys of the World, edited by Sharon Hudgins. Copyright © 2018 Sharon Hudgins. Reprinted with permission of Reaktion Books. All rights reserved.