Philosopher with Mirror, by Jusepe de Ribera, c. 1600. Rijksmuseum.

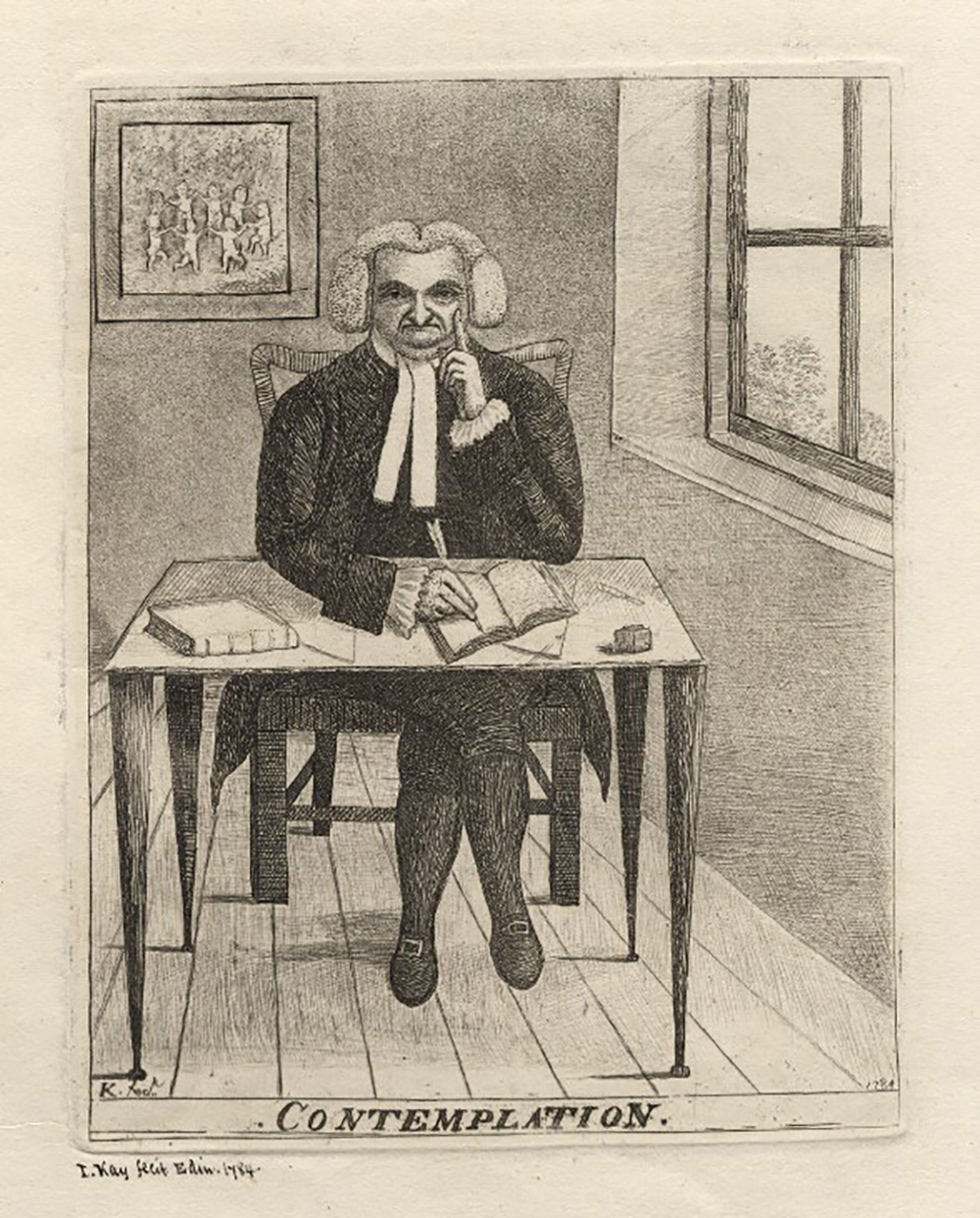

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, rich, strange, and Scottish, died at eighty-four in 1799. He was known for exposing himself: he exercised naked before the open windows of his estate and eschewed travel by carriage, insisting instead on riding his horse Alburac through the damp gray of every Scottish season. Like many other men of his ilk and era—Rousseau, Condillac, Mandeville—he speculated at length about language’s origins among our primeval ancestors. He maintained, incorrectly but not unlaudably, that fully articulate speech first appeared in the Black civilization of ancient Egypt; that certain Native American languages were mutually intelligible with Gaelic; and, most notoriously, that orangutans were humans, though just too lazy to learn to speak. For Rousseau orangutans’ humanity was only a hypothesis, but Monboddo asserted it as fact so insistently that the universal wit Samuel Johnson likened him to a man with a tail, but without the shame to try to hide it.

The Scotsman should be remembered less indulgently for attempting, in 1778, to thwart the successful suit for liberty of Joseph Knight, an enslaved man brought by John Wedderburn from Jamaica to what Knight and his supporters maintained was the free soil of Scotland. Johnson’s friend and future biographer, the Scottish lawyer James Boswell, wrote to Johnson to inform him of the outcome. Eight judges ruled for Knight’s freedom—and with it the end of slavery in Scotland. Four ruled against it, including Monboddo, who, as Boswell reported, maintained that slavery should be honored as lawful, as it was present “in all ages and all countries, and that when freedom flourished, as in old Greece and Rome.” The classical pomp of Monboddo’s legal logic perhaps rested on more local foundations: his desire to keep his mastery over a Black man he called Gory.

During Johnson and Boswell’s tour through Scotland in 1773, Boswell had enticed his friend into going “two miles out of his way” to dine at Monboddo’s “wretched” estate, as he relayed in a travel journal of the trip published a year after Johnson’s 1784 death. Johnson and Monboddo got along tolerably well during their dinner, but Johnson betrayed his host almost as soon as he was out of his sight. For, as Boswell tells us, after Gory conducted the two tourists back to the main road, Johnson asked Gory if he’d been baptized; in exchange for the yes, Johnson tipped him a shilling. Johnson’s subtle question likely sought an angle to sue for Gory’s liberty. Johnson, an abolitionist, would continue to raise toasts to the success of slave rebellions and persist in mocking Monboddo’s affectation of dressing up like a farmer in a “little round hat.” For his part, upon Johnson’s death, Monboddo said that he knew of no man more “invidious and malignant,” none more likely “in private conversation…to cavil at and contradict everything that was said.” On the same occasion, Johnson’s servant and editorial assistant Francis Barber, a man brought to England enslaved, received a legacy of money, Johnson’s papers, and a gold watch. As for what Monboddo intended to leave Gory at his death, or even whether Gory outlived him, we might be able only to guess.

Monboddo left the rest of us his multivolume Of the Origin and Progress of Language, his Antient Metaphysics, and his preface to a translation of Marie-Catherine Homassel-Hecquet’s Histoire d’une jeune fille sauvage, first rendered into English as An Account of a Savage Girl, Caught Wild in the Woods of Champagne. The book told the story of a “young wild girl,” christened by the French as Marie-Angélique Memmie Le Blanc. In 1731 the teenage Le Blanc had turned up in northern France, hungry for raw meat, armed with a club, and speaking incomprehensibly. Captured by a local nobleman in Songy, educated by nuns, and then, as her fame grew, supported by the unreliable patronage of French nobility—including the queen herself, Marie Leszczyńska—Le Blanc became the object of fascination among Enlightenment intellectuals, who saw her as a living witness to our species’ first long era of lawless barbarism. She was human to this audience, certainly, but perhaps only potentially so, just like the several “Homo sapiens ferus” listed in the 1766 edition of Carl Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae: the Wolf Child of Hesse, the Cow Boy of Bamberg, the girl of Champagne, and others.

In his 1747 “Épître II sur l’homme” (Second Epistle on Mankind), Louis Racine—grandson of the dramatist Jean Racine—folds Le Blanc’s story into his account of human development, introducing a Memmie Le Blanc who “tore apart living animals, satisfying her hunger with still-twitching morsels.” As Le Blanc explained later, she had shared these meals with her traveling companion, a Black girl roughly her own age, but the two had become separated not long before her capture. Le Blanc was accused of having eaten her friend, no doubt because anthropophagy fit so neatly into Enlightenment narratives of human development. Repeating the accusation, Julien Offray de La Mettrie’s 1747 L’homme machine (Man a Machine) heads a set of stories about French cannibals with Le Blanc, imagining her reproaching herself for what she had done, proving, to his own satisfaction, that even “the wildest and most savage” creatures, animals included, must feel some remorse.

Julia Douthwaite’s excellent treatment of Le Blanc in her 2002 book The Wild Girl, Natural Man, and the Monster collects still more contemporary attempts to make sense of, or exploit, Le Blanc’s story. The closest we have to Le Blanc’s own words are from Homassel-Hecquet, an ex-nun, carpet manufacturer, divorcée, Jansenist heretic, and biographer of both the aunt who raised her and Le Blanc. In the April 1755 issue of the Mercure de France, the explorer Charles-Marie de La Condamine explains the second book’s origins. Condamine had met Le Blanc a decade prior and had helped install her temporarily in a Parisian convent. His personal acquaintance with Le Blanc, as well as his fame as a writer, led to rumors that he was the true author of the Histoire d’une jeune fille. No, he insisted; barring some editorial excisions of certain stories that struck him as nonfactual or only hearsay, the Histoire is entirely the work of a widow named Madame H… (as her name appears on the book’s title page), who had befriended Le Blanc and collaborated with her on a book to help her “obtain a more comfortable situation” after the first enthusiasms of royal patronage began to run dry. They must have succeeded, for when the sixtysomething Le Blanc died in Paris in 1775, she left no heirs and an estate worth squabbling over.

In 1765, while in Paris to ascertain certain facts in a notorious inheritance suit known as the “Douglas Cause,” Monboddo and his clerk William Robertson took a side trip to a building at the corner of rue Saint-Antoine and rue Vieille du Temple, ascending to the top-floor abode of Marie-Angélique Memmie Le Blanc. Condamine had made the introduction. Monboddo was certain that Le Blanc existed midway between the only latently linguistic orangutan and fully articulate humans like himself. Upon their return, Robertson translated Homassel-Hecquet’s book into English. Supported by Monboddo’s introduction, and published by the respectable house of Kinkaid and Bell, Robertson’s translation was key to spreading the story of Le Blanc among Anglophone intellectuals. And having furnished himself with such a perfect specimen of intermediate language, Monboddo would go on to produce Le Blanc in all his works whenever he felt she might help his theories of the “slow and insensible degrees [by which] we have passed from the mere animal to the savage, and from the savage to the civilized man.”

All we know of the conversation between the judge and Le Blanc is what Monboddo tells us—and what was reported somewhat disloyally to Boswell and Johnson by the other person in the room: Robertson, who observed that during the conversation Le Blanc mixed up “what she imagined with what she remembered,” but that she also “perceived…Lord Monboddo forming theories and she adapted her story to them.” We can only assume that French was the only language they had in common, although Le Blanc must have interspersed it with samples of other languages she had used before. She was performing for Monboddo the role of the primitive, whose rules and expectations she very well may have learned from what had been written about her in the papers. What she herself thought about all this is irrecoverable.

Monboddo deduced that Le Blanc was not an “Esquimaux,” as the French commonly believed, and that she had passed through the Caribbean on her journeys before escaping a shipwreck on the coast of France. These conclusions at least approached the truth, which is more than can be said about Monboddo’s key theses about Le Blanc’s first language. It was, he reports, “little better than inarticulate sounds from the throat, in the formation of which the organs of the mouth have very little store. For she told me”—note the slight distance marking the construction of a shared story—“she did not move her tongue at all in speaking, and that, when she came to France, she had no use of her tongue, except in swallowing.” He writes that she laughed strangely, as “she did not open her mouth as we do, but made a little motion with her upper lip and a noise in her throat, by drawing her breath inwards.” What little she can remember of her American tongue sounded to Monboddo like “squeaking…uttered through her throat,” “little better than animal cries,” in which “everything [is spoken] with open mouth.” He concludes that the language, somewhat more elevated than the “guttural sounds” of the orangutan, must be Huron, which “upon the whole seems to be little better than animal cries from the throat, of different tones, a little broken and divided by some guttural consonant.”

But Monboddo had no more direct knowledge of the language he calls Huron—better known as the Iroquoian language Wyandot—than he did orangutan gutterings. Monboddo came at his conclusions through Gabriel Sagard’s 1632 Le grand voyage du pays des Hurons (The Long Journey to the Country of the Hurons) and a similar work from 1703 by the French soldier and wanderer Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, baron de Lahontan. The second volume of Lahontan’s Nouveaux voyages de Mr. le Baron de Lahontan dans l’Ámerique septentrionale (New Voyages to North America) ends with a brief account and short dictionary of the Huron language. Lahontan judges the Huron language “very pretty,” while also observing that the Iroquois “never shut their lips when they speak.” He and Sagard both complain of being unable to teach the Iroquois to sound a b, p, or m. Musical, open-mouthed, lacking the dexterity of tongue and lips necessary to sound certain key consonants: in this respect, their portraits accord with Monboddo’s paraphrase. Lahontan’s own record of a conversation with the (let us assume largely invented) Huron Adornio elsewhere in his book has his native informant offer the same arguments put into the mouths of civilization’s critics at least since the ancient Greeks, who likewise indulged themselves in longing for the simpler, lost era of humanity’s Golden Age. Yet however misguided and paternalistic he was, Lahontan had a sympathy for Hurons quite unsuited to Monboddo’s supercilious, parochial urbanity.

Monboddo little esteemed any language whose sounds he found difficult to transcribe in Roman script. He did not limit his scorn to “savages.” In Antient Metaphysics, Monboddo said that the Chinese must conduct their abstract thinking and matters of law, art, and science only in writing; the spoken language, in his assessment, is “the most defective, and the most incoherent language, that is now to be found in the world.” What Chinese and Huron each lack, at least to his hearing, is the full articulation of consonants and differentiated sounds Monboddo believes necessary for abstract concepts and complicated cultures like his own.

His mistaken conclusions may be blamed on classical grammatical theory. Monboddo was tirelessly devoted to the ancients, an admirer of the peculiar freedom of slavocracies famous for always having Homer at hand. He might have found ballast for his sentiments in old linguistic handbooks such as the fourth-century Instituta artium (The Principles of the Arts), which divides sound into eight parts, including “articulated, which humans speak, and which can be expressed in writing,” and “confused, either animal or inanimate, which cannot be expressed in writing,” like the whinnies of horses, the roar of wild beasts, the hissing of snakes, the singing of birds, and the beating of waves. Beliefs like these, common among classical and medieval grammarians, assume that since certain sounds cannot be retransmitted in the notational form that is understood to be an incontestable sign of reason, the sounds themselves must be mere noise. Writing needs articulation. And articulation, Monboddo argued, could not occur until human sociality became complex enough to necessitate splitting ourselves from the slack-jawed incoherence of our orangutan parents.

The belief that the divisibility of sound is a hallmark of articulate language, requiring the full use of the mouth, lips, and tongue in ways Monboddo would recognize, is obviously of a piece with self-serving beliefs concerning social complexity and rational abstraction. The guttural speaker is presumed to express only simple needs; the musical speaker, somewhat more complex. But for the arts and sciences and law, for any need more than just the immediate requirements of the body, what is needed are consonants, sounds that separate vowels from vowels, enclosing sounds into tidy, manageable, retransmittable units. Monboddo believed he and his consonants had summited vocal development. His theories don’t earmark space for a stage above articulate consonants that would leave him in the position of a cacophonous outmoded savage.

I presume Monboddo could never imagine himself transitional, just as he could not imagine himself being Memmie Le Blanc’s object of study. In an argument with Boswell about primitivism, Johnson said that, unlike Rousseau, Monboddo did “not know he was talking nonsense.” The judge believed little but what he already thought he knew. When Monboddo was informed that new anatomical studies of the orangutan found nothing in them that could have shaped articulate speech, he countered that natural scientists had proven their case only for one species, that of the Borneo but not the Angolan variety. Monboddo transmuted the Huron language into something only barely differentiated from orangutan noise, despite having read Sagard’s and Lahontan’s hodgepodge dictionaries, which included such complicated concepts as Hondioun (to be a man of sense), Onnonstè (covetous), Skenon (peace), and Achetek (tomorrow).

Had Monboddo given up trying to fit Le Blanc into his Origin and Progress of Language, he might have heard something from her quite other than what he expected to find. He would have found a girl belonging as much to the eighteenth century as he did. The puzzle of Memmie Le Blanc’s first few decades has been corrected in the twenty-first century, largely by Serge Aroles, the pen name of French surgeon Franck Rolin, whose two books on les enfants sauvages, feral children, declare Le Blanc the only fully authenticatable feral child, and then set out the facts.

From the port records of Marseilles, Aroles established that Le Blanc was likely of Fox—that is, Meskwaki—origin, from the Great Lakes region, enslaved as a young girl after surviving a French massacre. Finding herself in the household of Marie-Charlotte Charest, who became through marriage the Madame de Courtemanche, Le Blanc was brought to Marseilles in 1720 after Inuits burned Courtemanche’s Labrador home. Denied landing until she paid customs fees on the ship’s cargo of cod, Courtemanche seems to have been rescued by a local silk merchant named Ollive, who took nothing in exchange but Le Blanc. At Ollive’s manufactory, just north of Marseilles, Le Blanc seems to have met a Black girl, perhaps of Sudanese origin, and the two escaped together.

Le Blanc next turns up in the records nearly a decade later. She was nineteen, alone and far from Marseilles, in northeastern France, having made her way across a country devastated by plague. At some point during all this, she is said to have been dyed black, as Monboddo explains, “with a view, no doubt, to make her pass for a negro.” After her capture in Songy, she was scrubbed until her “natural white” color returned and taught to speak French, eat French food, and become a good Catholic. She is said to have been helped along in her conversion by being bled by a surgeon “to change her habit, and put French blood into her veins.” Her health thereafter was fragile, and she retained, Monboddo writes, “nothing of the savage but a certain wildness in her look and a very great stomach.” And, it seems, she became a good enough performer to keep herself alive.

Le Blanc lived among and used a variety of languages, most of them probably largely forgotten by the time Monboddo found her. None of them were ever Wyandot, although more recent studies of the language show that it does, in fact, have only the m among the labial consonants—which of course has nothing to do with any supposed proximity of the language to animal noise. For what it’s worth, Le Blanc’s own first language, Fox, an Algonquin language, does possess the labial consonants m and p. Monboddo may have misheard her, or she could have acquired new accents as she came to work with other tongues. The club Le Blanc carried when she turned up in Songy had her name written on it in some otherwise unrecognized and unrecorded language, and she referred to the club itself with a word said to be Caribbean: boutou. I can imagine the characters on the club being Arabic or some other script little read in eighteenth-century France, carved by someone in Ollive’s silk factory. The girl she traveled with through France until her capture also taught her some of her words, like broutut, for food (without knowing any Arabic myself, I think the word could have been قوت).

That combination of North American, Caribbean, and African languages, assembled by a girl who may have liberated herself from slavery at the age of ten, is witness not to some precultural existence but to a welter of negotiations and making do in circumstances of appalling necessity. Memmie Le Blanc is no more a primeval figure than Monboddo himself. He thought he was meeting his ancestor. Though he was wrong, he still did meet someone who made him possible, just as she and others like her made the rest of his modern world through their labor and through their losses. Language had been made in that world not by a “savage” but by a girl, uprooted, uprooted, and then uprooted again, among speakers of other tongues, and then perhaps still more terrifyingly alone. Had Monboddo cared to pay more attention to the woman he met and a voice he thought not quite of his time, he could have been something more to us than an unwitting artifact of his own terrible era.