Watercolor of Lhasa, Tibet, c. 1850. Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0).

Readers were keenly interested in the accidents, dangers, and spiritual crises that befell travelers en route. In the end, though, they wanted to find out how travelers overcame such travails. Open expressions of frustration are therefore to be found only in jottings not intended for public view. Such notes were made by Alexander von Humboldt. Yet perhaps no document is more revealing than the journal kept by the mysterious Thomas Manning.

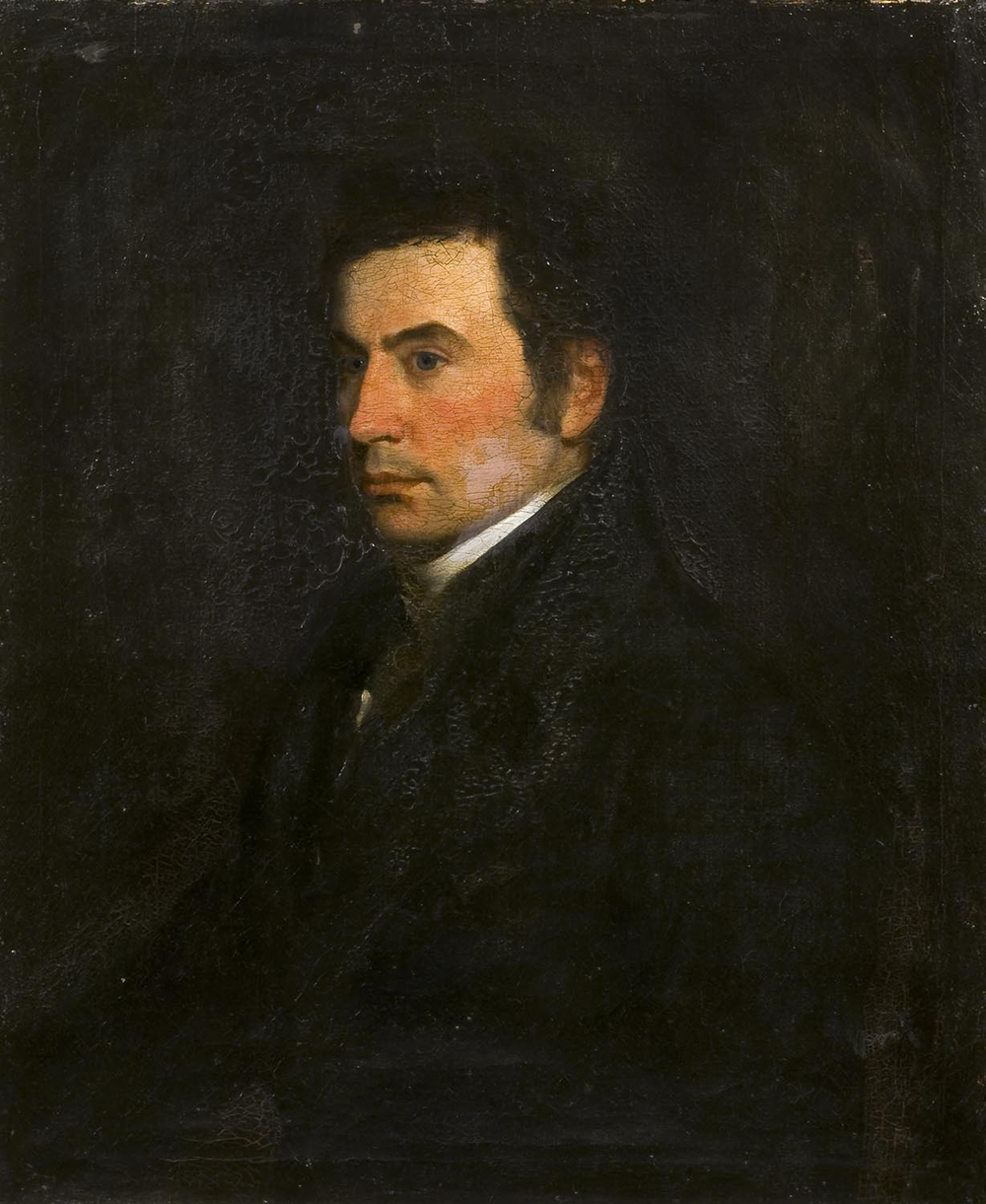

Until the end of the nineteenth century, Manning was the only Englishman ever to have set foot in the holy city of Lhasa. Born in 1772, the vicar’s son from Norfolk had broken off a promising career as a mathematician to study Chinese in Paris: at first with Joseph Hager, then under the tuition of a native speaker. Initially motivated by an interest in comparing the language with Greek, he became ever more fascinated by Chinese culture as his studies progressed. His friend, the famous essayist Charles Lamb, advised him: “Read no more books of voyages; they are nothing but lies.” But Manning was determined to travel to China and Independent Tartary. On the recommendation of Sir Joseph Banks, the president of the Royal Society, the East India Company gave Manning the opportunity to sail by company ship to Canton and reside in their factory from 1807 to 1810. In November 1807 he applied to the viceroy of Canton for the position of court astronomer and physician in Peking. When the Chinese authorities turned him down, he decided to make his way instead to the Chinese protectorate of Tibet.

In August 1811 Manning set off without official authority, papers, or financial support from Calcutta to Bhutan, accompanied by a single Chinese servant. Proceeding via Giansu he reached Lhasa, whose celebrated attraction, the Potala Palace, was known in Europe only through a picture based on Johann Grueber that had appeared in Athanasius Kircher’s China Illustrata (1667). On December 17 Manning was received by the ninth Dalai Lama, a seven-year-old boy. Manning gave him a piece of brocade, two brass candlesticks, and a flask of lavender water—not out of disrespect but for lack of more valuable gifts—and requested Tibetan books in return. On April 19, 1812, he was pressured by representatives of the Sino-Manchurian protectorate to leave Lhasa. In India he refused to share his experiences with anyone. He then returned to Canton to resume his Chinese studies. In 1817 he joined the embassy of Lord Amherst as an interpreter. On July 1 of the same year we suddenly find him conversing with Napoleon on Saint Helena. The extravagantly bearded Manning was considered something of a buffoon and an eccentric. In 1829 he finally returned to England and retired to a cottage near Dartford, surrounded by his huge collection of Chinese books. He died in 1840 without having published a single line. His travel notes did not see the light of day until 1879, when they were edited from his surviving papers.

Thomas Manning’s journal shows him to be an exact observer, acerbic commentator, and free spirit who never allows his perspective to be clouded by partisan British concerns. Manning has no interest in gathering the kind of “useful” information that official India expected of its emissaries and spies. Tibet’s geopolitical significance in the imperial “Great Game” then getting under way is a matter of complete indifference to him. One of his recurring themes is the overbearing manner of the Chinese in Tibet, which he often compares with the no less distasteful posturing of the British colonial overlords in India. Manning displays an immunity to the era’s clichés about Asia (both positive and negative) that was shared by none of his contemporaries except Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, who was a generation older. He is equally insusceptible to the mood of dumbstruck awe that seemed to grip other travelers when confronted with exotic spectacles. His first sighting of the Potala Palace has a very different effect on him: the swampy ground at the base of the castle reminds him unpleasantly of the Pontine Marshes in Rome. The palace meets with his passing approval (“it seemed perfect enough”) but the architecture strikes him as neither exotically alien nor immediately comprehensible: it “eluded my attempts at analysis.” The following chapter begins not with the expected description of the city of Lhasa but with a lengthy discourse on Tibetan hats.

Manning was one of the better writers in his generation of British travelers to Asia, perhaps the best. When he complains about the barren slopes of southern Tibet, he does so without resorting to a prose style that is equally barren in its abstraction. Instead: “A pot of young growing onions at one corner of the room was the greenest thing I had seen for a long time.” His writing is affected neither by lachrymose self-pity nor by the self-aggrandizing vanity that leads the romantic Chateaubriand, traveling around the same time, to push himself to the forefront of each scene. Manning describes his sorrows with unique psychological insight and unfeigned anguish: loneliness, extreme temperatures (including the difficulty of writing with fingers that are frozen half stiff), the consequences of unsuitable clothing, the torments of rheumatic illness, the creeping loss of faith in his own vision, his shame at having to pick off the fleas that infest his body, his need to finance his trip once his money runs out by selling off his belongings piece by piece, and his emotions on encountering others, from hatred of his treacherous environs to deep wonderment at the holy child on the Potala throne. On September 18, 1811, for example, a little way behind the Bhutanese border, he records this expressive entry:

The snow! Where am I? How can I be come here? Not a soul to speak to. I wept almost through excess of sensation, not from grief. A spaniel would be better company than my Chinese servant. Plenty of priests and monks like those in Europe.

Manning was one of the most honest Europeans in Asia and also one of the least prejudiced. He neither believed in European superiority nor sought to put Asia on a pedestal. Perhaps he never shared his experiences because he sensed they would not be understood. One would give a great deal to know what he discussed with Napoleon.

Excerpted from Unfabling the East: The Enlightenment’s Encounter with Asia by Jürgen Osterhammel. Translated from the German by Robert Savage. Copyright © 2018 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.