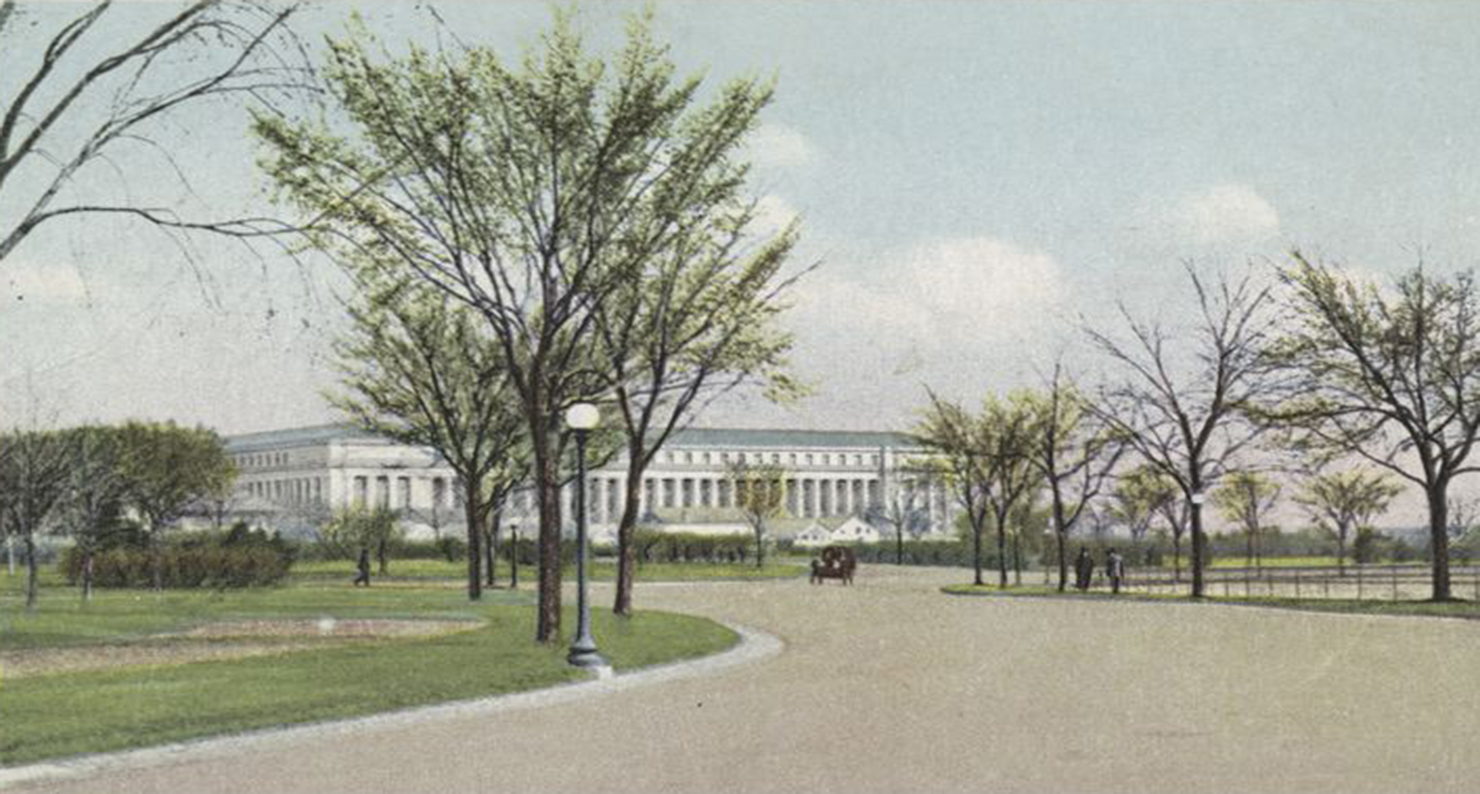

Bureau of Printing and Engraving, Washington, DC, c. 1915. The New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

The main building of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing sits on the southern edge of the National Mall, just across Fifteenth Street from the groves of cherry trees that festoon the Tidal Basin. The massive Neoclassical building, which opened in March 1914, occupies more than an entire city block, with a 224,000-square-foot vault and nearly ten acres of floor space for its thirteen hundred employees.

It epitomized the tremendous growth of the federal government in the decades following the outbreak of the Civil War. The agency did not even exist when the war began. Federal officials quickly realized that the nation’s money supply was inadequate to meet the financial exigencies of the war, so in 1862 Congress gave the Department of Treasury authority to begin engraving, printing, trimming, and inspecting paper money. With five employees, Treasury official Spencer Clark launched what eventually would become the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (it got its permanent name in 1874). By century’s end, it employed more than 2,300 people in its cramped plant on the corner of Fourteenth and B Streets SW. By World War I, employment topped 8,400.

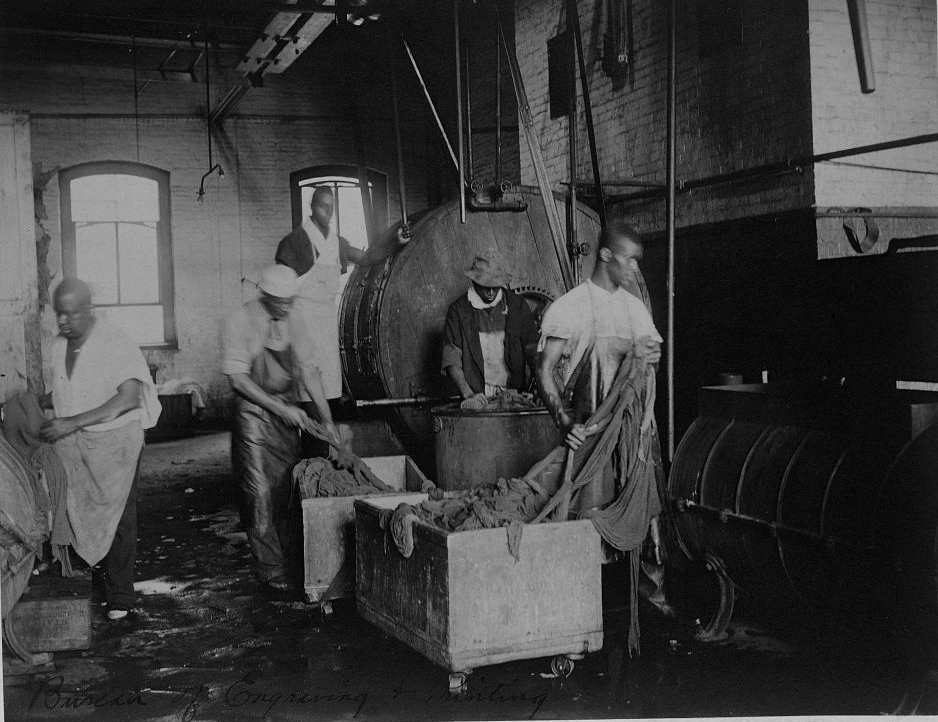

Much of the bureau’s work was hard, noisy, and dirty—more akin to an industrial factory than a white-collar federal agency. It attracted hundreds of both Irish immigrants and black workers from nearby neighborhoods. Male printers and their female assistants endured low pay and notoriously poor working conditions. Women at the bureau were among the first federal employees to organize a union. Bureau work may have been difficult, but like other federal jobs it offered black workers a measure of employment security, social mobility, and prestige, as well as insulation from the racism of the private labor market.

The agency hired its first black female employee, Frances Flood, as a printer’s assistant in 1890. When two white printers balked at working with her, the Republican chief of the bureau fired them, earning widespread praise from the black community. Black applicants thereafter flocked to the agency. By 1893, about a third of the bureau’s examination applicants were black and nearly one hundred black women worked as printer’s assistants.

But the federal government could be a fickle friend. Even after the civil service reforms of the 1880s, the fortunes of black employees in federal government jobs remained vulnerable to shifts in the political winds and changes in leadership. At the bureau, the doors of opportunity closed soon after the appointment of Kentucky Democrat Claude Johnson to head the agency in 1893. Within a year, fewer than ten black printer’s assistants remained. A Civil Service Commission investigation condemned the firings, yet Johnson remained on the post. Only with the return of Republican rule in 1897 did the bureau reopen to skilled black employees. By 1908, the number of black women printer’s assistants had climbed past two hundred.

Racial problems within the bureau flared again after Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected president in 1912, mirroring tensions within the federal bureaucracy and the city at large. During Wilson’s two terms in office, race relations within the federal government became perhaps the most important issue facing the city’s black residents.

Rosebud Murraye had been working as a printer’s assistant at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing for nine years when Wilson took office in March 1913. A native Washingtonian officially classified as “mulatto” by the census, she was born in 1885 and graduated at age nineteen from Scotia Seminary in North Carolina. Shortly after graduation, she took the civil service examination and earned an entry-level position in the bureau. She worked her way up through several promotions and by 1913 had reached, she wrote, “as far as I could go.”

Murraye and her coworkers at the bureau found themselves on the front lines of a renewed battle over segregation in federal departments that gained intensity after Wilson’s arrival in the White House. Virginian by birth, academic by training, Progressive by politics, Wilson catapulted from the presidency of Princeton to the governorship of New Jersey to the White House in less than three years. The first Southerner elected to the presidency since before the Civil War, Wilson embodied the regional reconciliation among American whites that had taken place since Reconstruction.

Many of Wilson’s appointees also embraced Southern ideals of white supremacy. Like the new president, they did not see a contradiction between Progressivism and segregation. Soon after his inauguration, Wilson replaced all but two of his predecessor’s black appointees with white men, and his administrative appointees quietly encouraged the racial segregation of federal workers, building on sporadic efforts that had begun under Presidents Roosevelt and Taft. With Wilson’s blessing if not his direct orders, administration officials isolated black workers in “Negro corners,” forced them to use “colored” toilets, and even erected a few “Whites Only” signs in federal buildings. When challenged by activists to explain the growing segregation in his government, Wilson argued that physical separation of the races was necessary to avoid racial “friction…discontent, and uneasiness,” and thereby both promote efficiency and protect black workers from further discrimination.

Emboldened Southern Democrats in Congress attacked the city’s residual integrated customs, reintroducing bills to segregate streetcars and prohibit interracial marriage in DC. Senator Francis Newlands of Nevada (the founder of Chevy Chase) proposed sending all black people out of the United States, while the National Democratic Fair Play Association lobbied hard against the appointment of black people to federal positions. “I have never seen the colored people [of Washington] so discouraged and so bitter as they are at the present time,” wrote Booker T. Washington in August 1913.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing was among the first agencies to feel the brunt of the new emphasis on segregation. One evening in early April 1913, not even a month after Wilson’s inauguration, Acting Secretary of the Treasury John Skelton Williams, a native Virginian, dropped by the bureau and was horrified to see that “young white women and colored women were working together side by side and opposite each other.” Williams put the bureau’s director, Joseph Ralph, on notice that the new administration would no longer tolerate such laxity.

Though initially worried that segregation within the bureau would be “unpracticable,” Ralph and other agency officials hurriedly complied with Williams’ request. They established separate toilets and lockers, and they set aside tables in the back of the lunchroom for black employees. Encouraged by the new, more militant spirit of segregation, some white employees initiated complaints about their black coworkers. In July, a white woman named Rose Miller complained about a black supervisor, Louise Nutt, in the Wetting Division; within a week, Ralph had replaced Nutt with a white man.

Like antebellum slaveholders who insisted that their slaves were happy with their condition, Williams, Ralph, and other administration officials claimed that not only did their black employees benefit from segregated treatment but they actually preferred it. Responding to criticism from Belle La Follette, the rabble-rousing wife of Progressive senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, Williams reported that there was no “general order” to segregate the bureau at all. The lunchroom tables for black workers were set aside simply because “it is believed that it would be better for them to associate together when eating their lunches.” Most black workers, Ralph said, complied without complaint. “Colored employees have expressed themselves as believing that arrangements of this kind, including separate toilet conveniences, were very satisfactory and proper,” he explained, “and it would seem that the claim of discrimination is made only by colored persons who do not desire to associate with members of their own race.”

Not everyone at the bureau was willing to go along with the new system. Not long after Williams’ initial visit in April, Rosebud Murraye and two other black printer’s assistants, Bertha Saunders and Maggie Keys, deliberately challenged him by repeatedly sitting at tables with their white coworkers, even after two employees, one white and one black, suggested that they move. Ralph called them into his office. With him was Charlotte Hopkins, a prominent white housing reformer, who lectured the women about accepting the way things were. When the women pushed back, noting that there actually was no separate lunchroom, just a waiting room next to the toilets, Hopkins responded, “Why will you go where you are not wanted? Do you know that the Democrats are in power? If you people will go along and behave yourselves, and stay away from places where you are not wanted, we may let you hold your places.”

Murraye, apparently, was unwilling to “behave.” According to Ralph, she was “impertinent” and “insolent” at the meeting. She and her coworkers decided to boycott the lunchroom entirely because they felt “our food choked us.” Not all the black employees supported them, however. According to an anonymous black employee, an “old time Negro Mammy” upbraided the young women for complaining and told them that they should be grateful that they still had jobs.

By spring 1913, Murraye and her partners in protest were stymied enough internally to consult an outside authority. They brought their complaints to a new organization that had first appeared on the local scene a year earlier: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). When that failed to solve their problem, Murraye and her colleagues eventually took their story to Belle La Follette, who published an interview with the three women in La Follette’s Magazine; Murraye later was fired for “insubordination,” and La Follette helped her find a new job.

As the federal government became less and less hospitable to black employment, the city’s appeal as a beacon of black advancement dimmed. Black migration to Washington slowed. By 1920, barely 25 percent of the city’s population was black, the lowest level since before the Civil War.

Adapted from Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital. Copyright © 2017 by Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.