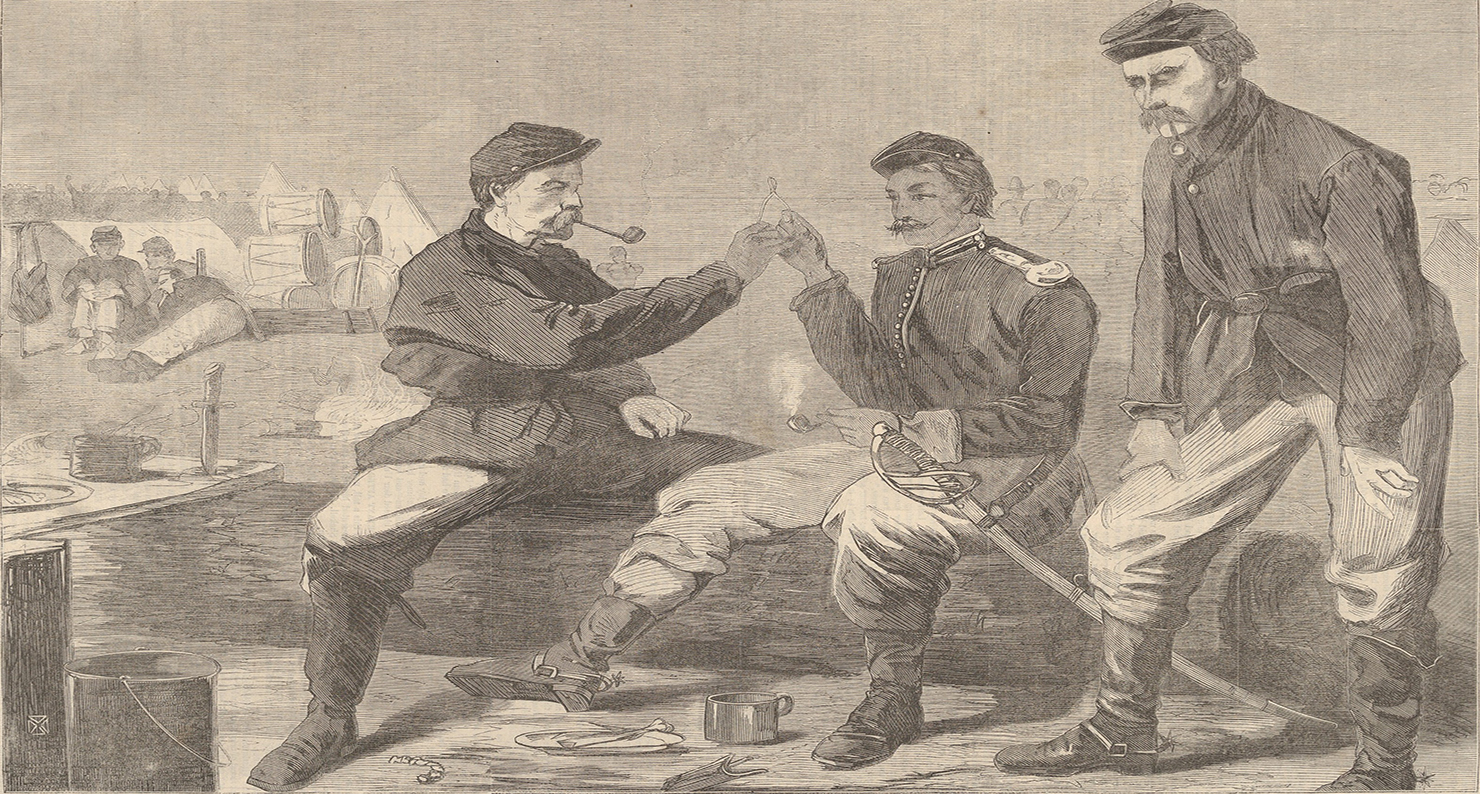

Thanksgiving Day in the Army—After Dinner: The Wish-Bone, by Winslow Homer, 1864. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928.

The Civil War was a tragedy. There were good people on both sides of the fight. And all that death and destruction surely could have been avoided if they had been more willing to compromise.

That’s the lie that white people told themselves after the Civil War to mask America’s original sin: the enslavement of African Americans. After a century of that story calcifying into historical memory, it clearly still has legs, as we discovered when Laura Ingraham interviewed White House chief of staff John Kelly on Fox News on October 30.

Confederate general Robert E. Lee was “an honorable man,” Kelly said. He added that “men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand” during the Civil War, and he warned against imposing our own views of “right on wrong” upon the past. And, in the sentence that stuck out most, he attributed the Civil War to “the lack of an ability to compromise.”

But antebellum history is littered with attempts to make a deal over slavery. Witness the Compromise of 1850, the Missouri Compromise in 1820, and—most notoriously—the three-fifths compromise in the U.S. Constitution, declaring that enslaved blacks would be counted as less than full human beings.

John Kelly’s remarks echoed a later compromise about the Civil War itself. Starting in the late nineteenth century, white Southerners and Northerners reached a negotiated historical settlement of the bloody conflict that had divided them. Those in the South conceded that secession had been illegal and that slavery was wrong, even if its evils had been exaggerated by abolitionists. Meanwhile, Northerners embraced the narrative—dramatized later in films like Birth of a Nation—that emancipation had freed blacks to rape and pillage until white rule was reinscribed in (yes) the Compromise of 1877.

But two major groups of Americans refused to sign this devil’s bargain. The first were African Americans, who underscored the cruelties of slavery and how the brief freedoms blacks won between the Civil War and 1877 were replaced by new oppressions: lynching, segregation, disenfranchisement, and more. The other dissidents were whites who called themselves neo-Confederates. Rejecting any hint of compromise, they insisted that the South was a near-perfect society until Yankees invaded and destroyed it.

Astonishingly, most white Southerners learned the neo-Confederate story in their schools up into the 1960s and 1970s. When I started to research history instruction in public elementary and secondary schools, I expected Southern textbooks to reflect the “both sides” narrative that Kelly repeated last week. I was wrong.

You could find Kelly’s version in popular Northern textbooks like David S. Muzzey’s An American History, which combined gentle criticisms of slavery and secession with stern condemnation of “Negro Rule” after emancipation. But the Southern texts took a much harder line: slavery was a positive good, secession was just and proper, and the North was fully at fault for the Civil War. John Kelly’s deluded quest for “balance” sounds almost quaint compared to the die-hard Confederate apologia that Southern white kids encountered in their classrooms.

In the United States, textbooks have always been chosen by local and state authorities rather than by a centralized national agency. So book selections are also heavily influenced by citizen organizations, which can apply strategic force upon the relevant officials. When I encountered the Confederate interpretation in Southern textbooks, I went looking for the pressure group behind it. And that’s what led me to Miss Millie.

“Miss Millie” was the popular nickname of Mildred Lewis Rutherford, one of the most important Southern figures that Americans know the least about. Born into a wealthy slave-owning family in 1851, Rutherford became the principal of a female academy in Athens, Georgia. She was an early and active member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, working her way up to become the organization’s “historian general” in 1911.

From that perch, Rutherford led the effort to purge Southern school textbooks of “Yankee” sentiment. That meant eliminating any books that tried to strike a balanced or neutral stance, “on the order of ‘we thought we were right,’ rather than ‘we were right,’” wrote one Confederate military veteran in 1902. “We did know we were right then, and we do know it now,” he added. “And we have the right, therefore, to insist that our children shall be told the truth about it, and we should be content with nothing less.”

Rutherford sent hundreds of women into classrooms and school offices to make sure their truth remained unqualified into the next generation. They came armed with her pamphlet, A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks. It provided a handy checklist to help them define and defend Confederate orthodoxy.

“Reject a book that speaks of the Constitution other than [as] a compact between Sovereign States,” Rutherford instructed, “that calls the Confederate soldier a traitor or rebel, and the war a rebellion…that says the South fought to hold her slaves…that speaks of the slaveholder of the South as cruel and unjust to his slaves…that glorifies Abraham Lincoln and vilifies Jefferson Davis.”

To Rutherford, the first point was the most important one. If the Constitution was an agreement between states rather than a national bond of citizens, then each state retained the right to leave the nation when it so chose. So it was the North—and not the South—that had violated America’s founding compact, by using force to prevent secession. “There was a rebellion,” Rutherford told her assembled aides at a UDC convention, “but it was north of Mason and Dixon’s line.”

Nor was the war about slaves, who, according to Rutherford, “were the happiest set of people on the face of the globe, free from care or thought of food, clothes, home.” Why, then, did the North invade the South? Rutherford’s pamphlet blamed it all upon Lincoln, whose imperious and vengeful character led him into a war of conquest. Hardly a suitable model for young children, Lincoln used uncouth language and once even denied the divinity of Christ. By comparison, the Confederacy’s president was a paragon of virtue, she argued. Davis “never stood for coarse jokes, never violated the Constitution, never stood for retaliation. Lincoln,” Rutherford wrote, “stood for all of these.”

But wherever Rutherford and her lieutenants looked, Southern textbooks flouted these Confederate truths. Angry correspondents reported that some history books still praised Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, which Rutherford called unconstitutional. Nor were other school subjects immune from the “Yankee” virus. One observer found that New Orleans schools taught music from a book that included “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” the iconic fight song of the Union Army. In Texas, an arithmetic textbook asked children to calculate Union general Ulysses S. Grant’s age on the day he captured Vicksburg.

After Confederate veterans petitioned Texas governor Thomas M. Campbell in 1908 to remove the math book from the state’s list of approved texts, its publisher issued a new edition that replaced the offending “Yankee word problem” with a more regionally appropriate one. The revised version asked students to determine the amount of time that elapsed between Texas’ independence from Mexico and its annexation into the United States.

The Texas episode illustrated a common pattern: when Confederate organizations complained, textbook publishers altered their wares. Some book companies issued so-called mint julep editions to satisfy the Southern market, expunging words such as treason and rebellion. But Rutherford and her aides found that many districts continued to use “Yankee” versions, which included the hated language of shared valor and responsibility.

In response, the UDC sponsored essay contests that exposed children to Confederate mythology in case their textbooks failed at the task. State and local chapters offered prizes to the best essays drawing on interviews with ex-slaveholders, who presumably would teach youngsters about the benign nature of the institution. Slavery was “the happiest time of the negroes’ existence,” read a winning entry in 1915 by one Virginia high school student. “The slave was a member of the family, often a privileged member. He was the playmate, brother, exemplar, friend, and companion of the white man from cradle to grave.”

The civil rights movement and the court-ordered desegregation of Southern schools led to the eventual desegregation of textbooks. By the 1980s, black heroes such as Frederick Douglass began to populate Southern textbooks, and Mildred Rutherford’s pro-Confederate doctrine had largely disappeared. But it still seeps in now and again.

Seven years ago, a Virginia parent found that her daughter’s history textbook falsely stated that “thousands” of African Americans fought for the Confederacy. (See: the war wasn’t really about slavery! Slaves supported our side!) In 2015 a mother in Texas complained that her son’s book included slaves in a passage about immigrant “workers,” as if Africans simply decided to sail across the Atlantic to get better jobs.

In both cases, the publisher pledged to revise the offending sections.

No one today will say a kind word about slavery, at least not in polite company. “It is disgusting and absurd to suggest,” White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said, “that anyone inside this building would support slavery.” But John Kelly’s comments did seek to exculpate white people who defended slavery, including Robert E. Lee—and only a month after the president said that there was “hatred, bigotry, and violence on many sides” in Charlottesville.

Millie Rutherford wouldn’t have been happy about Kelly’s efforts to indict “both sides” for the Civil War, but she would have endorsed his paean to General Lee. Until her death in 1928, Rutherford insisted that Lee was not guilty of treason; the real traitors were the Yankees. Kelly may hold the Confederacy and the Union equally responsible, for their supposed failure to “compromise,” but the upshot is the same: Lee is off the hook.

It’s hard to know how many schools—in the South or outside of it—still teach that. But at the University of Georgia in Athens, more than two hundred students currently reside in Rutherford Hall. It was erected in 1939 to honor Mildred Rutherford, whose female academy had closed in 1931; today, the academy’s building houses UGA’s Carl Vinson School of Government. The Rutherford Hall dormitory was refurbished in 2013 but retained the classical Southern style of its original design, including stately outdoor columns and a grand marble staircase. Miss Millie would be proud.