Adapted from Attensity! A Manifesto of the Attention Liberation Movement, published this month by Crown.

In a beautiful poem entitled “Saint Francis and the Sow,” the American poet Galway Kinnell imagines an encounter between the legendary animal-loving saint and a somewhat worse-for-wear fat pig, lying in a stinking sty and nursing a squirm of muddy piglets. There isn’t much action in the poem. All that happens is that the saint comes over and puts his hand on the sow’s head. That’s it, really. Except, somehow, this small gesture is depicted in the poem as effecting some sort of nameless current of vitalizing glory that tingles all through the scene—a current that runs through the body of the broken animal, through her brood, and, by extension, through the world itself. The current is described as a “remembering” (of the sow, by the sow) of... SOW! “Sowness” is what is recalled, and made magnificent, in this act of touch that is also an act of mutual recollection. The sow and the saint, and we, the readers, become inward, for a moment, with “the long, perfect loveliness of sow,” as the final line of the poem puts it.

What has happened?

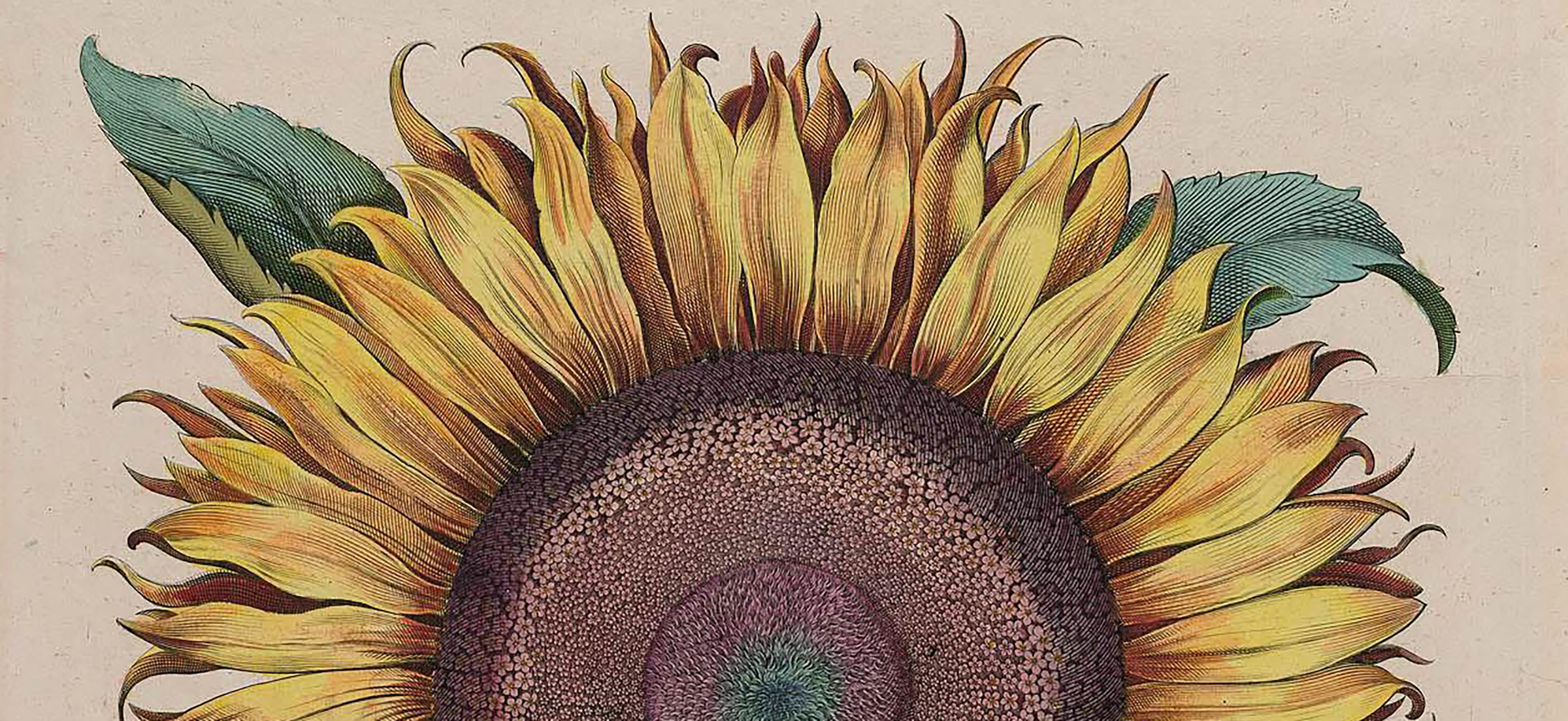

This poem launches with something like a theory of everything, which it states in its opening lines: “The bud / stands for all things.” Which is to say, it is the contention of the poem that everything in the world is properly understood as “bud-like”—meaning, everything in the world is a flower waiting to “happen”; waiting, that is, to open into its florescence. And Kinnell (or is it Saint Francis?) offers a concrete account of what causes the bud of things to burst into full blossom: even “those things that don’t flower” (in any botanical sense) actually can, we are told, “for everything flowers, from within, of self-blessing.”

If this is the case, though, then perhaps there is nothing to be done? We need only step back, and the beings of the universe (perhaps even the objects, too) will simply go about their mystical business of blooming-to-themselves. But this is not, in the end, what the poem asserts. While it is true that “everything flowers, from within, of self-blessing,” it is also the case that, we are told, “sometimes it is necessary / to re-teach a thing its loveliness.”

This is the exquisite moment at the heart of this beautiful and important poem: the world flowers, and the world flowers on account of its native graces; and yet, sometimes, it is indeed necessary to “re-teach a thing its loveliness.” It is this that Saint Francis effects in the poem, as he lays his hand on the big, sad, ill-fated pig, and in that gesture causes the beautiful work of self-blessing to begin to work inside the “long, perfect loveliness of sow.” The gesture is the catalyst of an inner unfolding—a kind of strong spring sun that makes the buds uncoil into their full and open offering.

“Saint Francis and the Sow” is a poem about attention. Indeed, it is best read as an allegory of radical human attention, since it is precisely radical human attention that is the way we “reteach a thing its loveliness”—and in so doing, cause its bud-nature to flower forth. Is this mysticism? We would say no. A mystification? Not at all. A mystery? Sure. If you like. But that doesn’t make it wrong, or “fake,” or “just talk.”

That we can feel the space between ourselves and the stars—this, too, is a mystery. But life is made of such things. Truly.

There is a term in botany for the process by which a bud comes into flower: anthesis. Coming into flower means something specific to the botanist. It means the “maturity” of the organs by which the plant can reproduce. It means that the plant is ready to pollinate and to be pollinated, to seed forth. Anthesis means, then, the irreversible opening into the phase of dynamic beauty that is also a phase of readiness to come into communion with others—and in so doing, to expand more fully into the world.

What has happened to human attention over the last century is exactly what has happened to the prairielands of America: a monoculture. A botanist-Martian, dropped off in the middle of the United States, would likely look around and say something like “Wow, what a lot of corn! Not a very diverse ecosystem down here.” And that Martian would be right. Nearly half a billion acres of this country are pure monoculture, an area representing something like the whole state of Arizona—six times over. Those regions represent unrelenting miles of just one thing, stretching to the horizon: soybean, wheat, or, mostly, corn. But there is nothing “natural” about all this. Once upon a time, those monocultured farmlands teemed with more than a hundred different wild grasses, forbs, and sedges—tallgrass and shortgrass prairies so vast that early European explorers thought they had come upon an actual ocean of meadow, full of species never before encountered.

Every time we think about our attention, we should remember those prairies—and the monocultures that have replaced them. Because the attentional world we navigate today is monocultural: what we talk about when we talk about “attention” is, in fact, just one very narrow and specific (if also, now, totally dominant) species. It is the kind of attention that has been cultivated by a century of industrial “attention farming,” and we hardly remember all the other attentional modalities that it has displaced. Which attention has carpeted our landscape? The mechanomorphic, instrumentalized, stimulus-and-response kind of attention that became the central preoccupation of the military-industrial complex across the twentieth century. The kind of attention that focused on screen vigilance (key for radar monitors and the monotonous labor of regulating machines), and the tap-click incorporation of human beings into cybernetic systems (key for shooting down enemy craft, or making timed decisions in complex models). This was the kind of attention studied in laboratories, quantified by advertisers, and now optimized by AI-driven search engine algorithms. And it is the kind of attention too many of us find ourselves trying to defend, or improve, or manage in our daily lives. It is the kind of attention that our screen-time app monitors; it is the kind of attention we fret about when we talk about declining “attention spans” or worry that our kids have ADHD.

Some recent commentators have even gone so far as to call for a “rewilding” of attention, and this is a perfect way to think about it. The sweet work involves throwing on some boots and taking a long walk across the carpetfields of clonal soybean attention to find a little wedge of old-growth prairieland here or there at the margins. Aha! Look what is still flourishing in the foothills! Beautiful! Here are some all-too-rare species of attention, thriving in little ecosystems not yet plowed under by the attention frackers.

For instance, how about the one hundred and seventy-nine dues-paying members of the Phoenix Bonsai Society, who have been quietly working away at their small trees and recently celebrated their sixtieth anniversary. That’s a form of attention that has little to do with search-engine optimization. On the one hand, the shallow roots of a bonsai demand daily water, so caring for a trophy specimen requires about as much custodial care as a pet cat. On the other hand, the trees grow so slowly that they achieve their beautiful sculptural form across decades, and that means only a few shaping snips every year or so. What an unusual attentional nexus: nearly continuous nurturing, plus the long-long view of envisioning a form that will not emerge until well after your kid has graduated from college.

Or what about that special mode of attention that involves simply staring out the window? The one that the teacher called “distraction”? There’s a rare species, and one that begs for a little protection.

Maybe this is the moment to say a few words about distraction. On the face of things, distraction is precisely the opposite of “attention”—at least that’s the way the standard denunciations set things up: attention good; distraction bad. Indeed, this Manichean pairing can be traced all the way back through the key moments in a long history of fretful concerns around personhood, social order, and right living. Patriarchal denunciations of flighty, fashion-addled society women in the late nineteenth century never failed to decry the wandering eye, wandering mind, and general inconstancy of La distraite. Even more grave, distraction has been featured as a soul-snatching ruse of the devil across nearly a millennium of Christian devotion. Monks, priests, and the faithful laity—all of whom shared a sense that righteous living required a continuous focus on God—together saw distractibility as a perpetual peril to properly prayerful contemplation. So when a middle school teacher gets on the case of a “distracted” student, a long legacy of disciplining anxiety lies behind such an exchange.

And yet, the work of actually distinguishing attention from distraction proves philosophically tricky. After all, when I accuse you of being “distracted,” what am I really saying, if not “You seem to be paying attention to something other than what I’d like you to focus on”? Which is to say, “distraction” ends up looking a lot like unauthorized attention—or, to put it another way, attention that is not in line with the expectations of whoever’s in charge.

Is that all that can be said? And if so, is there actually no difference between attention and distraction? Is the distinction purely a matter of sociology? Of relations of power?

Not at all. Attention isn’t that narrow, determinate, track-and-trigger “focus” that facilitates frictionless integration of humans and machines. It is many, many forms of cognitive engagement and sensory awareness; it is faith, love, and life. It is a vast and diverse jungle, not a single, highly engineered cash crop. The work of emancipating human attention involves, among other things, again and again insisting on that diversity and complexity—on the range and richness of attentional forms.

So stop worrying about your “attention span,” and start thinking about how to put your hand on the brow of that tired old pig, and reteaching it the long, perfect loveliness of sow. To do that, you may need to meander a little. You may need to let yourself get distracted by what else the world contains beyond the vibrating notifications in your pocket.

It’s in this context that we’d do well to sift out the attentional valences of “distraction” itself. One brilliant commentator on the history of attention, Paul North, has gone so far as to argue that the deepest and purest forms of attention actually hide behind the disguise of so-called distraction: it is precisely those moments in, which we are most completely “checked out” of the expected attentional patterns and objects—when we are so immersed in a daydream or reverie that, when called to the matter at hand, we truly cannot even recall where we were or how we got there—that the most extraordinary experiences of human attention are achieved.

Realizing that there is something profound, and actively inspiring, in North’s paradoxical provocation tips us dizzyingly, yet again, to the edge of what language can do. Our terminology can obscure as much as it reveals, sometimes more. And our language for talking about our attentional lives is not especially well developed. Not only that, it has been systematically distorted by a century of narrowing attention-discourse. The work of Attention Activism includes the delicate and elusive work of staying absolutely true to the complexity, beauty, and specificity of our actual experiences—and declining the flattening simplifications of inadequate vocabulary.

One of the greatest philosophers of attention, the American psychologist William James, specialized in just that kind of fearless and expansive thinking. His work involved a live-minded preoccupation with the actual “phenomenology” of attention (the study of the experiences of perception, cognition, and “being” itself). And in pursuing that project, he came up with a lovely way of theorizing the “deep distraction” part of an attentive mind. In his telling, the pinpoint focus that locks statically on an object cannot really be called “attention” at all. For him, it’s really a kind of inert stultification. Imagine, for instance, the dead-eyed, glassy, vacant gaze of a human being going fully vegetative while scrolling on the phone. Is that “attention”?

James himself was dead by the time TV rolled around, but he knew that empty gaze, and knew that, regardless how long it lasted or how fully trance-like it became, it wasn’t the thing he was trying to describe when he thought about the operation of his own attention at its vitalizing best. On the contrary, James came to believe that in the healthy state a human mind was basically incapable of simply “staying with” a discrete object for more than a moment. It was, in his view, in the essential nature of human cognition to be dynamic, to be moving, to be constantly in what he called the“stream” of consciousness. The alternatives weren’t “focus” or “attention”—they were really just a kind of spirit-death.

Hold up a dime, ask me to give it my full attention. Instantly, I’m wondering what’s going to happen next. Sure, I can put my eyes on the dime—and I can even try to “fill my whole mind” with that dime. But in practice, James felt he could simply see, in the actual operations of his own consciousness under those circumstances, that the moment he confronted such a task, his thoughts were immediately departing from that object: I’m wondering why you asked me to look at the dime; I immediately suspect you’re trying to play a trick on me, so I am trying to figure out what you are doing that the dime is supposed to stop me from noticing; oh, and you really should clean your fingernails.

That right there, practically speaking, is what “paying attention to the dime” actually amounts to. And James called this out. Having decided that this was an essential feature of normal human sensory cognition (that, to put it bluntly, healthy humans are incapable of “attention” in the flat-footed sense of a dead-eyed and unwavering and complete “focus”), James proposed a truly brilliant account of what we actually mean when we talk about the beautiful thing that attention can be: for him, the genius of real attention is the ability, again and again, to bend the path of those moving thoughts back to the object. In other words, genuine attention, the phenomenology of human attention, is a kind of centripetal distraction. Imagine the lovely looping rings of a spirograph, as it petals out and away and then again back to whatever is at the center of its attentional whorl. Looks like a flower, doesn’t it? The bud stands for all things.

From Attensity! A Manifesto of the Attention Liberation Movement. Copyright © 2026 by Institute for Sustained Attention. Reprinted by permission of Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.