Georgia Landscape, by Hale Woodruff, c. 1934. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred T. Morris Jr., 1986.

Savannah is haunted. That’s the first thing tourists learn about this city at the northern end of Georgia’s hundred-mile coast—a notion solidified in the popular imagination by the success of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, both the 1994 book by John Berendt and the subsequent film directed by Clint Eastwood. Midnight revolves around a nouveau riche antiques dealer named Jim Williams. Berendt, formerly the editor of New York magazine, happened to be in Savannah in the early 1980s when Williams killed a roughneck rent boy; he chronicled the event’s reverberations through Savannah society, which he depicts as eccentric and decadent. “The whole of Savannah is an oasis,” an informant tells him. “We are isolated. Gloriously isolated!”

“I suspected that in Savannah I had stumbled on a rare vestige of the Old South,” Berendt concludes. This vestige isn’t exactly the plantation fantasy—for Berendt, the Old South seems to have something to do with an enduring, atavistic faith in certain habits and creeds. The white elite believe in social custom; they have their teas and luncheons. Williams, bred in small-town Georgia, is able to insinuate himself into this echelon, but he maintains connections to other worlds, too. Williams buttresses his defense with an extralegal approach: he engages the services of a black root worker named Minerva. (Related to hoodoo, root work is a West African–derived form of folk medicine or magic practiced in the South.) Williams explains to Berendt that Minerva had been the “common-law wife of Dr. Buzzard,” a famous voodoo practitioner. One of Dr. Buzzard’s specialties was in the legal realm, where he “was especially effective ‘defending’ clients in criminal cases. He’d sit in the courtroom and glare at hostile witnesses as he chewed the root.” After Dr. Buzzard died, Minerva continued his work both in and out of the courtroom. A central scene in the book is set in a cemetery: the midnight garden of the book’s title, where Minerva has Williams drop “nine shiny dimes” into the dirt while she communicates with his victim, whom she tries to persuade to “ease off a little.”

In some ways it was a familiar scene, and the notion of the southeast coast’s being “gloriously isolated” was not a novel proposition. Earlier in the century, a similar spirit undergirded another spooky book, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, a peculiar volume compiled in the 1930s by workers affiliated with the Federal Writers’ Project’s Savannah Unit. Other FWP workers in the South gathered oral histories of slavery; the Savannah Unit, under the leadership of a white woman named Mary Granger, embarked on a stranger and far more fraught mission. Inspired by the anthropologist Melville Herskovits, Granger believed the lack of outside influence had led black people to retain certain “African” cultural traits or “survivals.” Her idea of what these attributes were is expressed in the book’s title and in her introduction, which mentions “sorcery,” “root doctors,” “miracles and cures,” and “mystic rites.” One such rite would be familiar to Berendt’s readers: “Not very long ago when a man was arrested for murder,” Granger wrote, “his friends, wishing to save him, went to the grave of the murdered man, secured some dirt, and left three pennies on the grave.”

Who’s to say what did the trick, but Jim Williams was eventually acquitted, following his fourth trial. Midnight became a juggernaut, credited with boosting Savannah’s tourism industry while earning it a reputation as uniquely spooky—the U.S.’s “most haunted” city, according to a 2002 designation by the American Institute of Parapsychology (an honor conceded to be “more honorary than scientific”). The Minerva scenes were more or less tangential to the book’s action. Combined with the fact of the murder itself, the strange social scene surrounding it, and the city’s gruesome preexisting history (slavery, several nineteenth-century yellow fever epidemics), they nonetheless seemed to suggest a place imbued to its bones with the macabre—a place where the dead were unusually close at hand. In 2007 the scholar Glenn W. Gentry credited the book with sparking a “boom in Savannah’s ghost tourism trade,” which hasn’t really flagged. Visitors still tour the city in repurposed hearses, walk through colonial and antebellum cemeteries, and pay for admission into purportedly haunted mansions lining Savannah’s famous squares.

Published in 1940, Drums and Shadows was nowhere near as successful as Midnight, but its impact was at least as profound: if Berendt’s book helped shape Savannah’s reputation in the 1990s and beyond, Drums and Shadows did similar work for the whole of the Georgia coast a half century before.1

It continues to be a valuable source for historians, folklorists, the descendants of enslaved people, novelists, artists, and many others, though it was always a plainly fraught endeavor. If white writers traveling the American South in the 1930s in pursuit of what they perceived to be the most “exotic” aspects of people then living under the violent terror of Jim Crow sounds like an ethical and methodological train wreck—well, it is.

The topics Granger and her staff seek to cover are tendentious and narrowly construed: “We asked if he knew anything about conjure or spells.” “We asked if he could see and talk with spirits.” “Do you believe in dreams and ghosts, too?” The Savannah Unit’s questions circumscribe the information they receive, with answers rendered on the page in thick dialect that seems designed to emphasize the speakers’ backwardness. The interviewers persist in the face of resistance—“At first residents of the community were reluctant to talk about their superstitions and beliefs and their knowledge of conjure”—and even, at times, despite their subjects’ apparent confusion regarding the terms of the exchange. The federal interviewers ask a woman in Tatemville about a scar on her chest that they suspect to have some cultural significance. She has already told them that her father—from “duh ole country”—was marked on his forehead.

She repeatedly demurs when asked about her own scar, though: “Wut yuh doin?” she responds. “Is yuh gonuh sen me back tuh Liberia?” They have no such authority, of course, but the exchange gestures at a problem observed by scholars of the 1930s FWP interviews: a confusion over who exactly is asking the questions and why. Some subjects, understanding the interviewers as affiliated with the government, apparently mistook them for New Deal relief workers—the people who could cut the checks. The Depression is just one piece of the unacknowledged backdrop behind Drums and Shadows, whose interrogators are deeply incurious, hunting ghosts and curses to the exclusion of history or context. Their informants’ lives span some of the most consequential events in American history—not least slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the birth of Jim Crow—but these remain largely off-screen. As one passage goes: “We interrupted the old woman’s reminiscences about plantation days to question her about funeral customs.”

In Tales from the Haunted South: Dark Tourism and Memories of Slavery from the Civil War Era, the historian Tiya Miles attempts to account for the undying popularity of the Southern ghost, represented in books like Berendt’s and in Savannah’s robust ghost-tourism business. Tales of hauntings are a way of addressing painful histories, Miles suggests; they “do double work: they call to mind disturbing historical knowledge that we feel compelled to face, but they also contain the threat of that knowledge by marking it as unbelievable.”

In Drums and Shadows, those ghost stories also turn out to be—however fraught—a mode of historical preservation. The richest corpus to come from it is a collection of tales commonly referred to as “flying Africans” stories, described here in the words of Mose Brown of Savannah: “A man an his wife wuz brung frum Africa. Wen dey fine out dey wuz slabes an got treat so hahd, dey jis fret and fret. One day dey wuz standin wid some udduh slabes an all ub a sudden dey say, ‘We gwine back tuh Africa. So goodie bye, goodie bye.’ Den dey flied right out uh sight.”2

Recurrent in Drums and Shadows, such stories would come to occupy a treasured place in black American folklore and literature. The People Could Fly was the title story of a collection of folktales by the children’s author Virginia Hamilton, and flight is central to Song of Solomon, for which Toni Morrison borrowed not just these stories but certain words and names found in Drums and Shadows, too.

Some historians have linked the “flying Africans” stories to the events of Ibo Landing (also called Ebo Landing or Igbo Landing), a site on St. Simons Island where, in 1803, a shipload of enslaved people set to be delivered to nearby plantations rebelled against their captors. Refusing to surrender themselves to slavery, they walked into the marsh and drowned—or, perhaps, they flew back home. Scholars continue to explore the meanings and historical antecedents of these stories of flight. Do they symbolize the suicides of enslaved people as a means of resistance? Or something else entirely? In a 2017 article, the historian Jason Young proposed that, if they seem to defy the laws of physics, the stories can indeed be read as a rejection of the very Western scientific, legal, and philosophical epistemologies that justified slavery. None of the Savannah Unit’s interview subjects indicated they were speaking symbolically or metaphorically, Young argued. On this subject Morrison was avid. “If it means Icarus to some readers, fine,” she said in an interview. “But my meaning was specific: it is about black people who could fly.” Ghosts don’t comport with Western ways of knowing either, but people still look for them.

Drums and Shadows has enjoyed a long afterlife, but it was contentious even before publication; within the FWP, higher-ups considered it racist and amateurish. The historian Melissa L. Cooper explores the book’s backstory in Making Gullah: A History of Sapelo Islanders, Race, and the American Imagination, in which she names Drums and Shadows as one of the major texts that helped popularize the label Gullah. Today that word and a companion term, Geechee, are widely used to describe communities of descendants of enslaved people on the southeast coast. (Sapelo is a Georgia island accessible only by boat.) But “Gullah” was an external creation, imposed by white writers who, in the 1920s and ’30s, thrilled to the perceived primitivism of coastal residents, whom they thought more “African” than, for instance, the black people then arriving in Northern cities.

Julia Peterkin, a South Carolina writer, popularized this idea of Gullah in novels about a fictional black community, notably Scarlet Sister Mary, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1928. Granger’s subsequent Drums and Shadows would become, in Cooper’s words, “easily one of the most frequently cited and consulted works about Georgia’s Gullah folk.” Though the canon of works about Gullah people and places was substantially enriched later in the twentieth century—particularly through the input of black women writers and artists, including the filmmaker Julie Dash and the photographer Carrie Mae Weems—these early books established some broader tropes that would prove enduring, even inescapable. Even in the 1920s and ’30s, others were covering similar ground as Peterkin and Granger—Zora Neale Hurston, for instance, saw her explorations of voodoo in the South as a way to reclaim black cultural heritage, and her work famously embraces dialect. But the heavy focus Peterkin, Granger, and their ilk placed on a very narrow band of cultural practices, Cooper observes, obscured the broader social and political contexts of their subjects’ lives. She writes, “The men and women of Sapelo who pursued voting rights, education, Christianity, and landownership as tools through which they could shape their destiny were depicted as childlike and superstitious primitives who put their faith in gris-gris bags and root doctors to secure their future.” In an early draft of Drums and Shadows, Granger referred to her subjects’ “native African rhythmic sense” and wrote of “superstitious beliefs and ceremonial rites” as “an outward expression of the inward awe the Negro felt before forces he did not understand.”

Granger, Cooper explains, simply didn’t have the training or cultural wherewithal to process the information she received. She and her staff saw certain folk-medicine practices as evidence of African survivals, for instance, when their meaning may have been more prosaic: people couldn’t afford or lived too far from doctors. As for the spectral, Granger and her subjects may have been speaking different languages entirely. In Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project, historian Catherine A. Stewart wrote that white interviewers were ill-equipped to understand black informants who, “drawing upon the black oral tradition, often told ghost stories as a way of commenting on the injustices of white behavior and white racial codes in the segregated South.” Their white interlocutors took these coded tales as evidence of “the naivete and superstitious tendencies of black folk.”

In the introduction to a 1986 edition published by the University of Georgia Press, the late Coastal Carolina University professor Charles Joyner argued that Drums and Shadows, at the time of its publication, nonetheless offered a rebuttal to Southern historians who considered slavery a civilizing force for essentially uncultured people—here was evidence of culture, rich and deeply rooted. And here is where Drums and Shadows has proved useful. It wasn’t that enslaved people and their descendants lacked a culture—just, for centuries, the means to document it. Though mediated through the prejudices of its authors, the information in Drums and Shadows has helped both historians and descendants fill gaps in the historical record and identify cultural continuities and linguistic relationships. The late Sapelo Island activist and historian Cornelia Walker Bailey wrote in her memoir that it was through Drums and Shadows that she learned the names of the children of Bilali, “the most famous and powerful of all the Africans who lived on this island during slavery days, and the first of my ancestors I can name.” He was her great-great-great-great-grandfather.

Bilali was also a practicing Muslim, and Drums and Shadows provided scholars with details of enslaved people following Islamic traditions, including ritual prayer. It also contains words that linguists have been able to trace back to West African languages. Scholars, writers, and artists have taken the desultory detail presented in Granger’s work and given it, retroactively, context. In the book, such information often comes in imagistic flashes that suggest the much broader, vital, and often violent histories of the lives of these interview subjects and their ancestors—stories, for instance, of slavers using pieces of red cloth to lure people on the coast of West Africa, where they were kidnapped and sold over the water. What similar information might we know today if only somebody had thought to ask?

I often make the same drive the Savannah Unit would have made, down U.S. Highway 17, the two-lane coastal road where it’s still possible to get a sense of the old isolation: you can cross a river delta and see nothing but cordgrass and sky. Some of the best, least complicated parts of Drums and Shadows, usually introductory or transitional passages, reflect this lonely feeling. You get the sense Granger is rushing toward the good stuff, but it imparts a beautiful economy: “When we arrived, it was just getting dark. Black masses of trees were outlined against the sky. To the south a shining river curved into shadows. A little wind blowing up from the marsh tasted of salt.”

Now as then, this desolate feeling is illusory; the landscape demands a closer reading. I recall standing at a nature preserve called Harris Neck and looking out at what appeared to be wild land across the marsh. I learned later it was a private island where Ben Affleck owns a 6,300-square-foot mansion, referred to as “the Big House” and currently on sale for $7.6 million. The contrast with Harris Neck couldn’t be starker. When Granger visited, this was a farming community founded by formerly enslaved people following the Civil War. In 1942 it was seized for the construction of a military airstrip; after the war, Harris Neck became a national wildlife refuge. Descendants of the original inhabitants, cast to the outskirts of the refuge’s boundaries, are still agitating to return home.

Black land loss, one of Cooper’s themes, is what actually haunts Drums and Shadows. It haunts the Georgia coast at large. During the same decade the Savannah Unit conducted its interviews, Sapelo Island was purchased by the tobacco baron R.J. Reynolds, who bought out many of the black smallholders and consolidated them into one community. Like other barons of the southeast coast, Reynolds returned the land in meaningful ways to what it had been prior to the Civil War: a plantation, with himself as the owner. That none of this was mentioned in Drums and Shadows suggests there is indeed a ghostly force at work, something unspoken and, to chroniclers like Mary Granger, unspeakable: whiteness and white supremacy. And then there are stories not even alluded to in this book or any other. They just lie there on the land, undecoded.

Just as histories of slavery and racial subjugation hover in the background of most modern-day ghost tours—present but silent—they are similarly relegated to the margins of Drums and Shadows. Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil captured Savannah in a moment of transition, as the city began to step out from its isolation and let the world in, and then the book itself—surprisingly—supercharged that transition. In Savannah today, one house that sometimes appears on “haunted” lists is the Owens-Thomas House, built in the antebellum nineteenth century for a local merchant and slave trader, and later home to a mayor, George Owens. “The Owens-Thomas House is considered to be the pinnacle of old Savannah,” according to one tour company, “and with its long storied past, it is easy to see why the ghosts of its former guests and residents continue to roam the property.”

But recently the house, which is operated by the Telfair Museums, underwent a restoration that was also a kind of historical revisioning. It reopened in 2018 as part of a larger Telfair project called Slavery and Freedom in Savannah. Today the campus, renamed the Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters, emphasizes the ways that enslaved people experienced the space, both the masters’ house and their own living quarters beside the carriage house. (Previously the slave quarters, where up to fourteen people lived at a given time, acted as a kind of holding area for visitors waiting to tour the mansion.) There is little written evidence of how they lived, but one artifact they did leave behind was the original ceiling of their living space, painted “haint blue.” Symbolizing water or the heavens, haint blue is a famous color on the southeast coast. Enslaved people and their descendants painted it on ceilings and door and window frames to keep away the evil spirits.

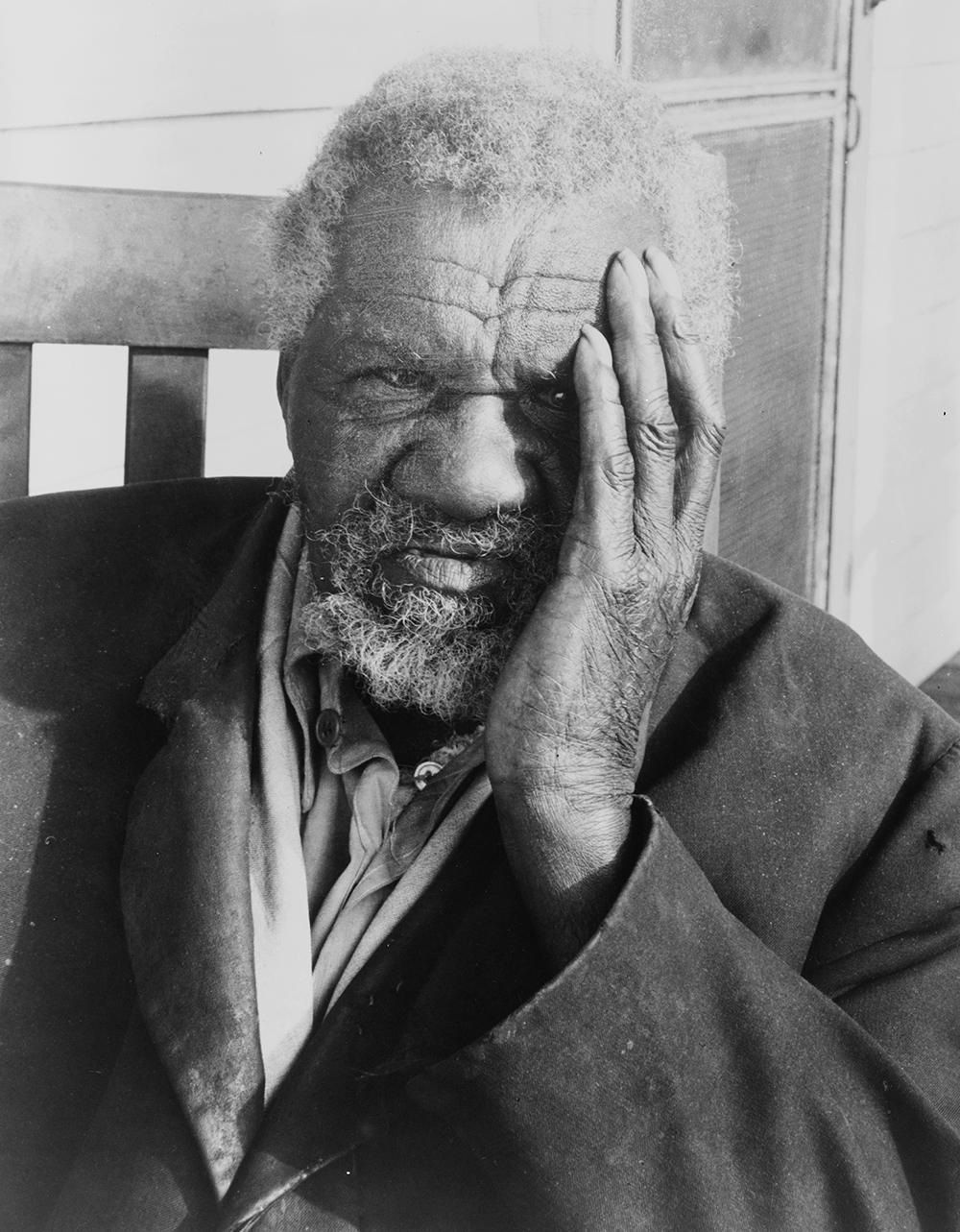

1 There are intriguing resonances between Drums and Shadows and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil beyond the graveyard coins. For instance, Midnight at one point mentions a Mr. and Mrs. Malcolm Bell. Mr. Bell, Berendt notes, was the “retired chairman of the Savannah Bank, former president of the venerable Oglethorpe Club, and a respected historian.” He and his wife, Muriel, had also been the photographers for Drums and Shadows forty years prior. ↩

2 Given its untrustworthy dialect, many scholars who cite Drums and Shadows render the speech in more standard English. Wuz and frum here exemplify one problem: they are pronounced no differently than was and from. The use of eye dialect emphasizes the speaker’s perceived ignorance. ↩