Group survival, argues anthropologist Robin Dunbar, necessitates strong social ties and frequent sharing of information among individuals. “In a nutshell,” he wrote in 1996, “I am suggesting that language evolved to allow us to gossip.”

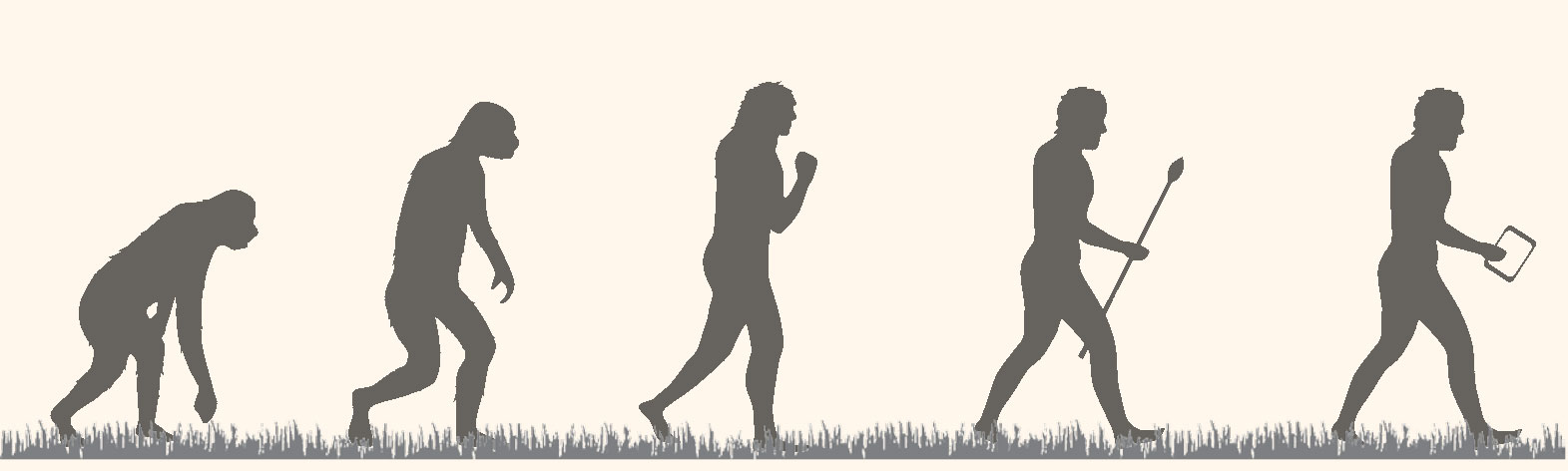

- Millions of years ago, African apes begin to devote time that could have been spent foraging to mutual grooming. The practice strengthens alliances and hierarchies, allowing populations to band together to ward off predators more successfully.

- Though Homo erectus, which appears around two milllion years ago, lacks a fully developed human vocal apparatus, “vocal grooming” in the form of meaningless chatter supplements physical grooming, resulting in larger communities.

- Homo neanderthalensis, which coexists with anatomically modern humans in Eurasia for millennia, seems never to have developed language—an evolutionary disadvantage for a species competing for resources with the linguistically developed Homo sapiens.

- Sometime after the emergence of Homo sapiens around 250,000 years ago, the species develops speech, which enables individuals to quickly exchange reports about others, including who might be freeloading. This more efficient means of managing a group permits larger, more complex populations.

- Extending Dunbar’s theory into the digital age, sociologist Zeynep Tufekci has found that active social media users are significantly more likely than their peers to express curiosity about other people’s lives and keep in touch with friends. Whether this confers evolutionary advantages remains to be seen.