This Prohibition thing has weakened the fiber and structure of our government and alienated hundreds of thousands of its most passionately loyal citizens, and sent them scuttling to live in Europe. Heaven knows how many would go if they could, and heaven knows how many men have had their feelings completely tempered by the belief they are overridden. I do not drink; I do not care to drink; that is not what I object to.

It has seriously injured scores of businesses, enormously increased the cost of government, and at the same time robbed that government of one of its greatest sources of revenue. It has put the liquor traffic—and the worst of the traffic that used to be associated with the liquor traffic—outside the law, where it and they can no longer be regulated by law.

It has imperiled our foreign relations and made us the laughingstock of the rest of the world. There is nothing that is as funny a joke throughout the world, at the present time, as the so-called American freedom. No country is as free as it was before we fought to make the world free for democracy, but there is no country that does not regard itself as free in comparison with the United States. It has weakened the moral fiber and the sense of personal responsibility of our people, driven them from a generally harmless relaxation to orgiastic relief in sex and crime and violence, and I beg of you to think of that phase, which I admit is not a legislative phase.

It has made liquor an obsession and a psychosis, the most important topic in America and almost the only one that concerns us with our government. It has occupied our government with affairs that are none of its business; brought it in to sit with us at dinner and by our hearthstone; filled us with an irritating consciousness of being watched, ruled, and verboten. No government is any good that fills its citizens with that feeling. The best government in the world, throughout all history, is the government that governs least and of which the people have the least consciousness. When the people feel conscious of their government, it should look out.

It has committed us to the theory that several million pounds of prevention are worth an ounce of cure; that it is right to deprive millions of people of what they have used wisely and temperately in order to keep a few thousands from using it foolishly and intemperately. That is the theory of this law, and it has alarmed us with logical fear of extension, so that we, who have been forbidden a glass of beer today, may be forbidden tobacco or coffee tomorrow—or beefsteak because immoderate meat eating creates uric acid; or automobiles because the auto has made getting away easier for the criminal.

There is no limit to which this law may not be carried in its prying officiousness. If the law is right in principle, there is nothing in what you do today that may not be forbidden tomorrow.

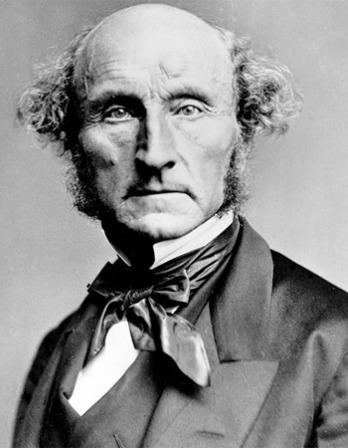

From a statement given to Congress during a hearing about Prohibition. Pollock began his career in 1898 as a drama critic for the Washington Post and later worked as a stage manager and press agent before turning to playwriting. “Before Prohibition I never saw a bottle of liquor in a theater before in my life…at the present moment, a dressing room without a bottle is almost as rare as a dressing room without a makeup box,” he said in his testimony. “Before Prohibition a man got a drink when he wanted it. Now he wants a drink when he can get it.”

Back to Issue