A person who sees only fashion in fashion is a fool.

—Honoré de Balzac, 1830Crusader Chic

Upon returning home, Crusaders brought with them styles that would upset Europe’s fashion hierarchy.

By Danielle Peterson Searls

The Crusaders Reach Jerusalem (from a set of Scenes from Gerusalemme Liberata), designed by Domenico Paradisi, c. 1689. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Elizabeth U. Coles, in memory of her son, William F. Coles, 1892.

Roland Barthes draws a distinction between the universal practice of adornment and what we call fashion. Fashion is not only clothes and accessories, it is also a language that harmonizes with a time and place. Along with the obvious reasons clothing was invented—“as protection against harsh weather, out of modesty for hiding nudity, and for ornamentation to get noticed”—Barthes says that fashion serves another essential function: storytelling. Wearing a particular item of clothing, writes Barthes, is “an act of signification and therefore a profoundly social act.”

For the early medieval period, clothes were statements of function and position. Stability and outwardly legible rank were important above all else; one dressed according to one’s station. The rigidness of this system stands in contrast to modern notions of fashion, which emphasize aspiration and fluidity—whether this is a countess deciding to dress like a queen or a suburban American teenager like a sophisticated Parisian.

The Crusades (1095–1291) were one of the earliest disruptions in the medieval world’s codes of appearance. In 1091 Pope Urban II declared that it was urgent to restore Christian control of the Holy Land. Religious enthusiasts set off to conquer; when they arrived in the Levant, they encountered the refinement of the Islamic courts, a developed consumer society, and well-dressed Muslim armies. While we think of the medieval period as a time of violent conflict between Islam and Christianity, and assume this animosity left little room for cultural exchange, there is also a story of artistic dialogue across geographical, political, and cultural boundaries. Viewed through the lens of clothes, the history of this period is marked by concord and cooperation, and stands in contrast to the military clashes of the Crusades.

“In a Sweat Shop,” by Jacob A. Riis, c. 1890. © The Museum of the City of New York / Art Resource, NY.

Travelers to the Holy Land encountered a new universe of fabrics and clothing—and returned home with powerful new desires. Exchange between the courts of the Latin West and Muslim caliphates eventually led to a revolution in aristocratic dress, with French courtly ladies deriving identity and recognition from the lavish silks of Baghdad, Constantinople, Alexandria, and Damascus.

It is hardly surprising that Europeans looked to the East for new fashions. Every scrap of silk in Christian Western Europe was imported from the East until the eleventh century. The vast majority of medieval Western art also points to other places and times: the Garden of Eden, the future resurrection, the court of Heaven, Jerusalem, and other sites of biblical history. To medieval Europeans, the East meant the holy places of Christianity, the Magi, and the early martyrs, and anything from the East had an aura of the sacred. The Crusades also opened the Holy Land to mass pilgrimage, a journey undertaken by a larger and more diverse group of pilgrims than ever before—thousands a year—who also observed the splendor of the Islamic world.

Knights and pilgrims, the majority of whom came from Capetian France, brought back souvenirs from their journeys, including textiles and other Muslim-made luxury objects. These were bought in the marketplaces of Frankish crusading states, were gifts from Islamic courts, or war booty. Many of these objects—bought, given, or taken—were in the supremely lightweight, flexible, foldable form of textiles: robes, pouches, turban wraps, veils. These textiles were like nothing most Europeans had ever seen.

European crusaders and pilgrims reached the Holy Land at the high point of an extraordinary textile culture. The Fatimid dynasty (909–1171) ruled an empire that stretched from North Africa to Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem. Accounts of visits to the Fatimid court in Cairo contain descriptions of magnificence, with textiles playing a large role in the visual luxury. Visitors were led through sumptuous courtyards, each courtyard draped in rich fabrics. One tent was decorated with images of every known animal, a fabric bestiary that took 150 workers nine years to complete. At the center of the court was a gold-curtained throne where the caliph sat in golden robes. The Fatimids were minority rulers, and intricate textiles were a way for the caliphs to legitimize their rule in the eyes of subjects and rivals.

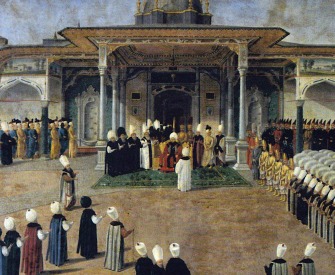

In Egypt silk was a stable currency with a fixed exchange rate. Merchants carried silk instead of cash, and tribute could be paid in silk rather than gold. The Costume Supply House was a major Fatimid government office, established by the first caliph in Egypt, with an initial budget of more than 600,000 dinars. It oversaw the production, storage, and distribution of official costumes for court functionaries, from the caliph to government clerks and their families and servants—a wardrobe from turban to underwear, with different outfits for summer and winter. To give a sense of the enterprise’s scale, Abu al-Futuh Barjuwan, only an administrator in the court, died with a wardrobe containing a hundred turban wraps, a thousand pairs of pants, and a thousand silk waistbands.

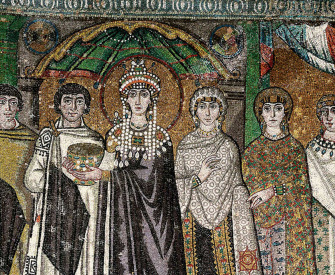

In Fatimid Egypt, the Crusaders also encountered something entirely new to them: a complex system of investiture that was widespread in medieval Islam. Investiture is the ceremonial reclothing of a person in special garments to create a new status. A ruler would bestow a garment, called a khil’a, sometimes with a ceremonial sword, on a court official, who would then be known as one of the “men of robes of honor.” Almost all of these ceremonial garments were woven or embroidered with gold in the eleventh century, with different levels of grandeur signaling different ranks. The khil’a ceremony is the origin of our word gala.

Originally the khil’a robes would have been ones a ruler had actually worn, containing a baraka, or “blessing.” The investiture ceremonies later became more symbolic; as honors were extended to thousands of followers, it was impossible for every garment to have been worn by an important ruler. (This led, of course, to requests by those set to have a khil’a ceremony for a robe that the caliph actually wore.) The core idea remained, however: the ruler was holy, with a radiant light that could be transferred by cloth.

It is impossible to trace the origins of robing ceremonies, although the biblical story of Jacob giving his coat of many colors to his son Joseph, or the Prophet Muhammad giving his coat to the poet Ka’b bin Zuhayr, have been presented as possible origins for the tradition. Over two thousand years ago, silk robes were also given out by nomadic kings in Central Asia to solidify relations between them and their subjects. Investiture ceremonies became central in all the states that developed out of Islamic conquests and grew particularly important as Islam spread. After the Fatimid period the tradition took on a strictly metaphorical meaning: a chronicler might say someone was “invested with a robe of honor” to mean he was appointed to a high office, even if no garments were involved.

For the Fatimids, however, robing involved actual garments, and the highest-status textile was the tirāz (from the Persian word for embroidery), a cloth with an Arabic-inscribed border. The inscriptions, also known as tirāz, were formulaic, beginning with a blessing, followed by the name of the caliph, the vizier, the place of production, and the date. Tirāz were made between 700 and 1171 in Islamic lands from Persia to Sicily, and reached their artistic height in Fatimid Egypt. The Fatimid caliphate had official administrative departments for tirāz textiles, which were linked to the mints; both tirāz and coins were made with gold and silver. The written word was the highest achievement in Islamic societies, and the signature of the caliph on tirāz had meanings far beyond those of the designer names on our own clothes. In the Fatimid world, an inscription on a tirāz wasn’t just a brand. It was magic.

Fatimid Cairo was also a place of relative cultural mobility, with something approaching a middle class—a world that surely surprised the Crusaders. The Fatimids were generally tolerant of Jews and Christians, and Cairo was a place of great religious intermixing. There were silks manufactured by royal tirāz workshops made for export to the West with invocations to the trinity applied on the silk. Makers of textiles, like mosaicists, worked for both Christians and Muslims. The Jewish upper class also imitated Fatimid court styles, copying textiles inscribed with Arabic script. A cache of 200,000 manuscripts and papyri found in the genizah, or storage room of a synagogue, in Cairo contains more than 750 trousseau lists appended to marriage contracts. They catalogue seventy different types of women’s clothes (half of them headgear) in sixty different fabrics, including robes with printed designs, checked patterns (plaid and checkerboard), set with jewels or pearl sleeves, gilded or embroidered with gold, or striped like “the flowing of the pen” (probably a fine pinstripe). Almost every new bride had a jūkāniyya, not mentioned in any Arab dictionary but probably a sleeved garment of linen, brocade, or silk. The word is perhaps derived from jawkān, the game of polo, which would mean it resembled a polo jacket; a short coat with narrow sleeves. Islamic laws restricting the colors worn by non-Muslims were not enforced in Cairo.

Many of these garments and textiles made their way back to the Latin West after the beginning of the Crusades, starting especially after the late 1060s, when unpaid Fatimid troops raided the royal treasury and plundered unimaginable quantities of luxurious goods to sell. Merchants, whose trade had been established under the Romans and had continued more or less uninterrupted, made many of these goods available in Mediterranean markets, including those sold to the Frankish armies. The scope of the liquidation was vast, and we now assume that most of the Islamic luxury objects found in Europe today were in the possession of the Fatimids until 1061.

The rock crystal ewers in the treasury of San Marco and in the Louvre, for instance, probably came to the West at this time. The San Marco ewer was most likely sold in Tripoli, after which it ended up in the Byzantine court in Constantinople. The Venetians acquired it in another pillaging—the second great event in the movement of Islamic luxury goods to the West—the 1204 Sack of Constantinople. The Paris ewer most likely took a different route to Europe. It was first given by King Roger II of Sicily to Count Thibaut of Blois, who donated it to the treasury of St. Denis, where it remained until it was moved to the Louvre in the eighteenth century.

Monstrosities of 1819 & 1820, by George Cruikshank, 1835. © HIP / Art Resource, NY.

Textiles also entered Europe as booty from the wars against Byzantine- and Muslim-controlled Sicily and southern Italy. Pope Benedict VIII sent Henry II a gold and jeweled crown that belonged to the wife of the Muslim emir of Sardinia. The crown must have been taken as booty when the island was recaptured. William of Tyre said the plunder after the fall of Antioch was so big “it was impossible to count or measure the gold and silver, the gems, silks, and valuable garments.” Geoffrey de Vinsauf described King Richard the Lionhearted’s army raiding a Turkish caravan in 1192 near Galatia and finding “gold and silver, cloaks of silk, purple and scarlet robes and variously ornamented apparel.”

The desire for these textiles in the West is well documented. When the Crusaders, men from relatively diverse backgrounds, saw the abundance of the Islamic courts, they wanted to possess such new and exotic finery. Knights coming from the lower nobility could fulfill these desires; they returned with a longing for uniqueness and originality after sharing in a knightly culture in which all knights emulated the highest noble ranks.

The adventure stories now known as the Old French Crusade Cycle, read and told to nostalgic French audiences from around 1190 into the fifteenth century, contain lush descriptions of Eastern textiles. In “Les Chétifs” (c. 1190–1200) Frankish knights encounter one Muslim leader with a tent that was

very rich, draped with brilliant silk,

and patterned green silk was thrown over

the grass,

with lengths of cut fabric worked with

birds and beasts.

The cords with which it was tied are of silk,

and the quilt was sewn with another

shining, delicate silk.

Readers enjoyed these specific, lush details. The colors and types of textiles even change in different manuscripts of the same story, as storytellers rushed to keep up with the latest styles: here the tent is draped in imperial Byzantine silk, but has purple stripes in another version, striped white silk in yet another.

A number of scenes show Crusaders dreaming of khil’a ceremonies or receiving honorific robes as gifts. In “Les Chétifs” one Crusader is given robes of honor by a sympathetic Muslim and then shares the robes with his companions in the mode of Christian humility and comradeship. In these tales common knights, not only the great heroes, imagine receiving fine robes.

In the Crusader epics, Islamic textiles also become an opportunity for social mobility, as anyone given such an outfit could wear it and undermine the hierarchies of appearance. As new textiles became available to more people, they became a sign not just of wealth but also of honor.

It is worth emphasizing that the new desires for exotic clothing started with men, not women. In fact, the Crusader epics are more likely to focus on the textiles worn by horses.In one tale a sultan, wanting to tempt the hero Godfrey of Bouillon with his wealth, is advised to bring out his white Arabian charger. While Godfrey resists, the poet and his audience succumb—not to the horse’s size and strength, but to its dazzling accessories. The horse was covered

with a rich silk of Carthaginian make;

the governor had a saddle of gold covered

with many images—

birds and maritime fish are worked on it

in enamel.

The saddle is very rich and of very fine

foreign manufacture…

There was never either reins or a saddle

made of better gold,

it was all done in scales of gold hung all

over the outside,

there were many emeralds and many

shining topazes.

The horse’s chest harness was extremely

admirable;

there was not a man in France rich enough

to have bought it,

for venom cannot poison the one who

uses it.

The horse was whiter than snow that you

see falling

and its head was red as coals in a furnace.

With a checkered vermillion siglaton silk

the horse was covered, they had cut it

very well:

you could see the white shining out

between the red.

The bridle it had on its head was worth the

honor of Pithiviers:

Few men in the world would not covet it.

The manufacture, materials, their places of origin (Carthage), design, visual effect, aspirational quality (not a man in France rich enough to buy it), and novelty add up to desire: all, or nearly all, men would covet it. Historians tend to talk of Crusaders’ wives back home launching the craze for Eastern textiles that swept across Europe, but this description is probably anachronistic, privileging the agency of women in a fashion universe that did not yet exist. Still, women were at least part of the craze for Eastern textiles: one observer described the Christian women of late twelfth-century Sicily who followed Islamic fashions: “For the feast of Christmas [in 1184] they go out clad in gold-colored silk gowns, wrapped in elegant mantles, covered with colored veils, with gilded brodequins on their feet; they flaunt themselves in church in perfectly Muslim toilettes.” Such a person would have been introduced to the glamorous variety of Eastern textiles (as well as spices and other imports) thanks to the Crusades, creating the desires an expanded commercial trade system would soon move to satisfy.

A new era of economic prosperity opened with the Crusades. Posts were established in Crusader states like Antioch, Tripoli, and Jerusalem; Acre, in what is now northern Israel, was the central marketplace and major port of the Franks in the Holy Land. The symbolic meaning of the Crusaders’ newly discovered textiles wouldn’t have gone far without a flood of actual clothes and garments to buy, sell, and wear in Europe.

The encounter with Islam also created the idea that textiles could have another type of value: they could contain honor. This made the textiles a site of fantasy: they were no longer simply about monetary value or luxury but honor or status as well—something they were already infused with in the Islamic context that now entered the West. It is also likely that the Eastern origin of these textiles helped give them a sacred aura that worked against the Christian tradition of rejecting worldly luxury. As early as the second century, Christian leaders such as Clement of Alexandria were thundering that the truly holy would be clothed in “the pure vestment, woven of faith, of those who have been shown mercy”; they would metaphorically wear Christ, not luxurious robes.

To call a fashion wearable is the kiss of death. No new fashion worth its salt is ever wearable.

—Eugenia Sheppard, 1960The new fabrics and costumes the Crusaders brought home inspired others to want rich and detailed clothes, with complex tailoring and fine workmanship. Patterns on textiles were introduced. Stockings were replaced with tailored leggings, draped garments with the cut-and-sewn. Skirts became long and flowing, with trains sweeping the ground, and silhouettes became fuller. One new type of full-skirted tunic, the bilaut, sometimes with kimono sleeves, became popular with both sexes. Women’s bilauts had a close-fitting tunic top that sometimes laced at the sides, and a skirt worn with two belts, one at the natural waist and one at the hip, where the skirt and top joined. Seams were concealed with decorative tape. This is recognizable as the fairy-tale Middle Ages presented by the Victorians and so well known today. The world of basic, functional European garments would never be the same.

At the distance of nearly a millennium, it is all but impossible to give a reliable history of any particular object that came back from the Crusades. Anyone studying the history of Islamic textiles will find the best-preserved objects in French churches. In addition to the innumerable textiles imported from the Holy Land for domestic use, extravagant textiles were presented in Europe as biblical relics. Muslim-made textiles came to fill church treasuries, as cloth that lined reliquary caskets, shrouds of saints, and relic wrappings covering the hair and bone fragments of the holy.

The Chemise of the Virgin, said be worn when Mary gave birth to Christ, is one of the rare Islamic objects transported to Europe before the Crusades. It is reputed to have been donated by Charles the Bald in 876 and is historically a ninth-century silk wrap, possibly a turban wrap. The Chemise was so sacred that the cathedral at Chartres was built to house it.

Only two fully intact Fatimid textiles exist: one is in Apt, in the Vaucluse in southern France. It is said to be the veil of St. Anne, the Virgin Mary’s mother. The other, the Holy Shroud, is in Cadouin and is said to be the cloth that wrapped Jesus when he was placed in the tomb. The Holy Shroud of Cadouin was a destination for thousands of pilgrims.

These robes quickly traded their identities as Islamic objects for Christian meanings. They can be regarded as a kind of spolia—like the ancient Roman columns incorporated in medieval and late antique churches—that used symbols and materials of a powerful empire to celebrate victory over a great rival.

Textiles that came back to Europe passed effortlessly and uncontroversially into liturgical use. Inscriptions with Allah’s blessing abound in Christian churches, transformed into orphreys, elaborately embroidered ornamental stripes or bands on ecclesiastical vestments. A textile with embroidered and woven Arabic inscriptions, quoting the Qur’an at length, might proclaim Muhammad the messenger of God and announce the name of the reigning caliph and royal manufacture in which the textile was produced, all while serving as a burial shroud for a Christian saint.

These objects would likely have been consecrated in a religious ceremony before entering the service of the church, in a sort of material baptism that erased any previous history. When these objects entered church treasuries through donations after many years of secular use as clothes and furnishings, their origins would by then have been obscured.

Europeans refreshing themselves on a balcony, Mughal, India, possibly Deccan, early eighteenth century. The British Museum.

Tirāz textiles with Arabic inscriptions started to be used creatively in Western art as well. There are some eight hundred known cases of late-medieval Italian painters putting their subjects—biblical characters, the Holy Family—in robes with Arabic script or tirāz armbands. Sculptors, too, gave the saints and holy figures crowding around the portals and cloisters of French cathedrals the same tirāz bands from the 1140s to 1160s. Arabic or Arabic-style inscriptions, the motifs most characteristic of Islam, became popular in the Latin West, with Western artists recreating Islamic motifs in paintings and sculptures.

The Holy Family, of course, could not have worn tenth- or eleventh-century Fatimid robes. Artists and church leaders simply got it wrong, taking what were really Islamic textiles woven for Muslim rulers and giving them Christian meanings. But the practice makes some sense if you reflect on the fact that these Islamic textiles were already hybrid objects. A tirāz might have Egyptian-style animals and a Byzantine neo-Persian pattern made by Coptic Christians for Muslim rulers, even before Crusaders brought it back to Christian Europe. And the church had tremendous confidence in its authority to reinterpret Islamic objects as Christian. They felt they could repurpose the spoils of conquest for their own ends.

The idea was that the Holy Family should be dressed in the best and most glorious possible clothes, and this is what glorious clothes looked like. Islamic script had the aura of the Holy Land. Artists didn’t try to replicate biblical styles; instead they used the tirāz as a marker of beauty or exoticism, giving fashionable details to European costumes. It is possible that Arabic script was occasionally thought to be Hebrew or another early Christian script, and if so it would have intuitively bestowed honor and authenticity on an object or painting.

It costs a lot to make a person look this cheap.

—Dolly Parton, 1994Interestingly, a tirāz of the highest quality, made as a robe of honor for an investiture ceremony—an object that had been blessed and was inscribed with the caliph’s blessing—retained its power to convey the sacred even after it was transported to Europe. Across very different cultures, the power of the garment remained strangely the same.

The new fashions—and the taste for them—spread wildly. For a culture like medieval Europe’s, which placed such importance on external marks of inner rank, this created a kind of class panic. A sense of order had been lost. Orderic Vitalis, a monk writing an ecclesiastical history in the early twelfth century, describes the French count Fulk le Rechin’s lamentable taste for pointy-toed shoes, which “encouraged a new fashion in the Western regions, delighting frivolous men in search of novelties. To meet it, cobblers fashioned shoes like scorpions’ tails…and almost all, rich and poor alike, now demand shoes of this kind. Before then shoes always used to be made round, fitting the foot, and these were adequate to the needs of high and low, both clergy and laity. But now laymen in their pride seize upon a fashion typical of their corrupt morals.” It only got worse, the fashions more outrageous, from big sleeves to mullets to goatees.

Carmelite monks who returned from the Holy Land in the summer of 1254 wearing striped robes launched a controversy that lasted more than thirty years, with ten successive popes wanting the Carmelites to give up the stripes for plain cloaks. The Carmelites continually refused. Sumptuary laws in Western Europe sprung up in the late thirteenth century, particularly from the Council of Montauban (1274–1291), prohibiting wearing the color purple in the street and certain furs, silks, and luxury ornaments. These laws restricted the wearing of noble clothes among commoners, and occasionally limited the number of gowns dukes and barons could buy per year, to reduce bankruptcies among the aristocracy. The timing of these new laws is not surprising, given the influx of new fashions occasioned by the Crusades.

The most well-known and representative enemy of these new fashions was the Cistercian Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), adviser to popes, preacher of the Second Crusade, pioneer of Marian theology, and reformer of the decadent Benedictine Order at Cluny. Bernard championed austerity and discipline, the restoration of the original rule of St. Benedict. He did not go in for clothes:

For the beauty that is put on with a garment and is put off with the garment belongs without doubt to the garment and not to the wearer of it. Do not, therefore, emulate those evil disposed persons who seek an extraneous beauty when they have lost their own. Deem it a thing unworthy of you to borrow your attractiveness from the furs of animals and the toils of worms; let your own suffice you. For that is the true and proper beauty of anything, which it has in itself without the aid of any substance besides.

The influx of Islamic fashions destabilized the Latin West, introducing new kinds of luxury and making daily elegance available. The church and aristocracy of the medieval world were prepared to incorporate the goods and textiles, but they were not ready for them to circulate outside the rigid social structures already in place. They were eager to use new, beautiful textiles for their own purposes. But when confronted with the insinuation of the ideas in lower classes, the impulses from on high—like those of Bernard of Clairvaux—were to regulate the ability to use new clothing and new modes of self-presentation. They were ready for new fashions to suit their purposes; they were not yet ready for fashion.