No matter how much cats fight, there always seem to be plenty of kittens.

—Abraham Lincoln,Deciding to Wait

Charles Mingus takes it slow.

At thirteen, my boy Charles arrived at the conclusion that there was more to life than people have time for. Important things came in such rapid succession that he’d hardly begun to solve a problem before another arose and each day burning questions were crowded out by new ones and disappeared into the past unanswered.

He began to realize he had some sort of mystic powers. He felt he was able to touch people, to contact certain souls in the next room or miles away or even those who had died. In later years he had this special kind of empathy with Farwell Taylor, an artist friend of his in Mill Valley, and they often experienced a mysterious awareness of each other while in different parts of the world.

Ever since Elsinore and the afternoon at Mr. Rodia’s, Charles had felt a telepathic communication with Lee-Marie. He was sure they were having the same dreams and thoughts and feelings at the same moments in time. So he wasn’t at all surprised when he boldly asked for her number and she answered herself and said immediately, “Oh, Charles, I knew it was you!”

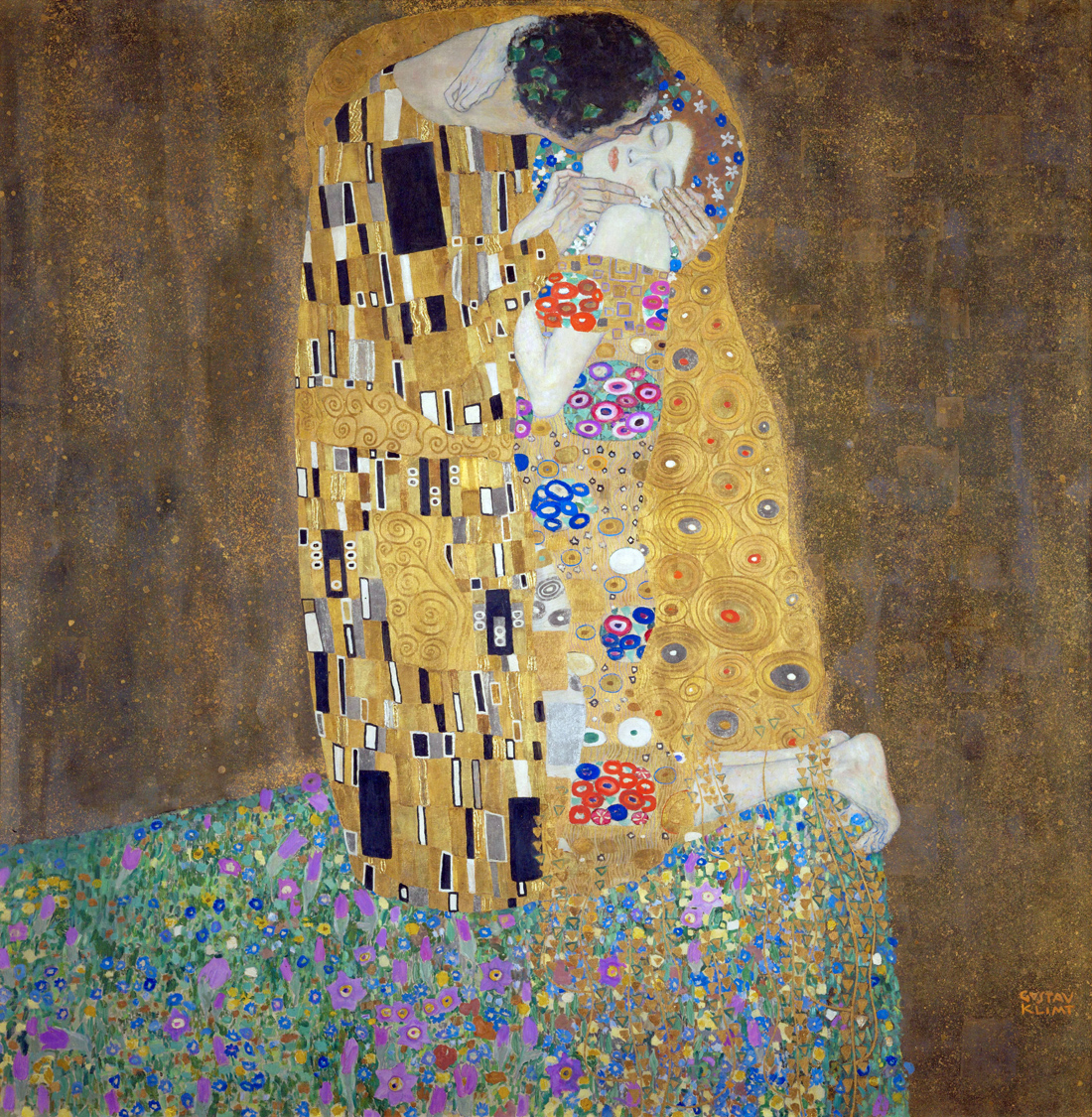

The Kiss, by Gustav Klimt, 1907–1908. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, Austria.

As if it were the most natural thing in the world and they saw each other all the time, he invited her to go to the show at the Largo in Watts on Saturday afternoon. He knew she’d say yes and she did. The rest of my boy’s week was full of anxious calculations. He’d already spent a nickel of his twenty-five-cent weekly allowance and he knew better than to ask for an advance. Admission price, a dime apiece. Ice cream sodas, fifteen each. He rummaged in Daddy’s vest pocket, stuffed with Chinese lottery tickets and poker chips, found an extra quarter and copped it without a qualm. Total, forty-five cents. Five cents short can be as big a problem as five hundred dollars short, depending on circumstances. He knew he had to cut-rate his way in somehow. The kids told him Stewart Harrington, the Largo Theatre doorman and ticket taker, was beyond bribery, but you could get an usher to sneak you in the back door for a nickel. Then you’d go out front, ask for a return pass, meet your girl at the candy store, pay for the sodas, take her back to the theater and buy her a real ticket and you’re both safe inside. Total, forty-five cents.

All goes well. In the dark theater they sit side by side, full of the love they’ve saved so long, dying to kiss and touch and hold each other but scared of being noticed by Lee-Marie’s sister Patricia sitting close by with their little brother. They think she must be aware of their wandering hands and uncontrollable deep breathing and fraudulent concentration on the movie screen they’re staring at but neither of them really sees. Charles’ hand, loving carefully, perfectly, slips into her sleeve to touch her naked little breast. Timid fingers feel around her nipple’s areola as it swells, hardens and throbs. His hand slides down and tugs and finally her blouse is pulled free of her skirt. She covers her lap and naked stomach with her coat as her slip is pulled away. His fingers crawl down the edge of her elastic panty band and press pleadingly. Her skin tightens to his touch, she bites her lips together with her teeth. Her stockinged foot caresses his leg. She spreads her thighs. Pains of delight crawl and squirm. Beads of warm perspiration seep into his palm as his fingers smooth the soft, fine little fuzz that grows from her navel down to her damp, hot pubis where a few scattered long hairs roll and twist around his fingers. This child, this woman, this wife! He holds her wrist as it slides inside his unbuttoned fly and his jacket covers her innocent, kneading hand. At last in a single thought together with little or no movement both reach a climax and turn to look into each other’s eyes, slowly nodding their heads as the gradual letdown comes. Their moist fingers untangle. They rise. Lee-Marie leans toward her sister and whispers, “Stay here. I’ll be back.” Together they go out to the unromantic theater parking lot. Without a word they open their mouths to each other, drink each other’s love taste, swallow, and in their magic oneness say at the same time, “I was you!”

“Is that what love is—being one, Charles?”

“I don’t know. But I felt your thoughts. I read your mind.”

“I did too!”

“We’ve always been like this, Lee-Marie.” Charles takes her little hands. “But we can’t do this again until we’re grown and old enough to be married. We’re going to wait.” And she cries, “But I love you, I love you! I’m yours and you’re mine now, tomorrow, forever!”

He buttons her blouse beneath the coat draped over her shoulders and they look deep into each other’s eyes, living for a brief moment on an isle of thought that exists until this very day.

Funny thing about love. My boy was thirteen years old and he understood that in the eyes of the world they were only two small children and their passion was against every rule of God and man. “Man” was the powerful and dangerous adults surrounding them.

He stayed away from her for five long years after this happened. Sometimes he’d ring her on the phone, listen to her voice and hang up quickly, or go all the way to Southgate to walk past her house hoping to see her moving about inside the imprisoning walls. Sometimes she waved from a window and he could see her smile and he wondered if there were tears in her eyes, for there sometimes were in his. But he felt she knew his love and it was only a question of time before her family would consent to their courting.

Charles Mingus

From Beneath the Underdog. In elementary school Mingus played in the Los Angeles Junior Philharmonic, but listening to Duke Ellington on the radio shifted his focus from Claude Debussy to jazz. His improvisation on the double bass made him the forerunner of the modern jazz movement; he regarded his music as a form of self-liberation, “the only place I can be free.”