I have learned much from disease which life could never have taught me anywhere else.

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1830Out of Sight

George Eliot follows a Good Samaritan.

Romola set out at once toward the village, the abandoned baby in her arms. As she passed across a breadth of cultivated ground, she noticed with wonder that little patches of corn mingled with the other crops had been left to overripeness, untouched by the sickle, and that golden apples and dark figs lay rotting on the weedy earth. There were grassy spaces within sight, but no cow or sheep or goat. The stillness began to have something fearful in it to Romola. She hurried along toward the thickest cluster of houses, where there would be the most life to appeal to on behalf of the helpless life she carried in her arms. But she had picked up two figs and bit little pieces from the sweet pulp to still the child with.

She entered between two lines of dwellings. It was time that villagers should have been stirring long ago, but not a soul was in sight. The air was becoming more oppressive, laden, it seemed, with some horrible impurity. There was a door open; she looked in and saw grim emptiness. Another open door; and through that she saw a man lying dead with all his garments on, his head lying athwart a spade handle and an earthenware cruse in his hand, as if he had fallen suddenly.

Romola felt horror taking possession of her. Was she in a village of the unburied dead? She wanted to listen if there were any faint sound, but the child cried out afresh when she ceased to feed it, and the cry filled her ears. At last she saw a figure crawling slowly out of a house and soon sinking back in a sitting posture against the wall. She hastened toward the figure; it was a young woman in fevered anguish, and she held a pitcher in her hand. As Romola approached her, she did not start; the one need was too absorbing for any other idea to impress itself on her.

“Water! Get me water!” she said, with a moaning utterance.

Plague in an Ancient City, by Michael Sweerts, c. 1650. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of the Ahmanson Foundation.

Romola stooped to take the pitcher and said gently in her ear, “You shall have water. Can you point toward the well?”

The hand was lifted toward the more distant end of the little street, and Romola set off at once with as much speed as she could use under the difficulty of carrying the pitcher as well as feeding the child. But the little one was getting more content as the morsels of sweet pulp were repeated and ceased to distress her with its cry, so that she could give a less distracted attention to the objects around her.

The well lay twenty yards or more beyond the end of the street, and as Romola was approaching it, her eyes were directed to the opposite green slope immediately below the church. High up, on a patch of grass between the trees, she had descried a cow and a couple of goats, and she tried to trace a line of path that would lead her close to that cheering sight when once she had done her errand to the well. Occupied in this way, she was not aware that she was very near the well, and that someone approaching it on the other side had fixed a pair of astonished eyes upon her.

Romola certainly presented a sight which, at that moment and in that place, could hardly have been seen without some pausing and palpitation. With her gaze fixed intently on the distant slope, the long lines of her thick gray garment giving a gliding character to her rapid walk, her hair rolling backward and illuminated on the left side by the sun, the little olive baby on her right arm now looking out with jet-black eyes, she might well startle that youth of fifteen, accustomed to swing the censer in the presence of a Madonna less fair and marvelous than this.

“She carries a pitcher in her hand—to fetch water for the sick. It is the Holy Mother, come to take care of the people who have the pestilence.”

It was a sight of awe: she would perhaps be angry with those who fetched water for themselves only. The youth flung down his vessel in terror. Romola, aware now of someone near her, saw the black-and-white figure fly as if for dear life toward the slope she had just been contemplating. But remembering the parched sufferer, she half filled her pitcher quickly and hastened back.

Forced March to the Front Between Lonie and Mitulen (detail), by André Kertész, 1915. Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Gerald Levine, B.A. 1960.

Entering the house to look for a small cup, she saw salt meat and meal; there were no signs of want in the dwelling. With nimble movement she seated the baby on the ground and lifted a cup of water to the sufferer, who drank eagerly and then closed her eyes and leaned her head backward, seeming to give herself up to the sense of relief. Presently, she opened her eyes and, looking at Romola, said languidly, “Who are you?”

“I came over the sea,” said Romola, “I only came this morning. Are all the people dead in these houses?”

“I think they are all ill now—all that are not dead. My father and my sister lie dead upstairs, and there is no one to bury them, and soon I shall die.”

“Not so, I hope,” said Romola. “I am come to take care of you. I am used to the pestilence. I am not afraid. But there must be some left who are not ill. I saw a youth running toward the mountain when I went to the well.”

“I cannot tell. When the pestilence came, a great many people went away and drove off the cows and goats. Give me more water!”

Romola, suspecting that if she followed the direction of the youth’s flight, she should find some men and women who were still healthy and able, determined to seek them out at once, that she might at least win them to take care of the child, and leave her free to come back and see how many living needed help and how many dead needed burial. She trusted to her powers of persuasion to conquer the aid of the timorous, when once she knew what was to be done. Promising the sick woman to come back to her, she lifted the dark bantling again and set off toward the slope. She felt no burden of choice on her now, no longing for death. She was thinking how she would go to the other sufferers, as she had gone to that fevered woman.

But with the child on her arm, it was not so easy to her as usual to walk up a slope, and it seemed a long while before the winding path took her near the cow and the goats. She was beginning herself to feel faint from heat, hunger, and thirst, and as she reached a double turning, she paused to consider whether she would not wait near the cow, which someone was likely to come and milk soon, rather than toil up to the church before she had taken any rest. Raising her eyes to measure the steep distance, she saw peeping between the boughs, not more than five yards off, a broad, round face watching her attentively, and lower down the black skirt of a priest’s garment, and a hand grasping a bucket. She stood mutely observing, and the face, too, remained motionless. Romola had often witnessed the overpowering force of dread in cases of pestilence, and she was cautious.

Raising her voice in a tone of gentle pleading, she said, “I came over the sea. I am hungry, and so is the child. Will you not give us some milk?”

A moment after, the boughs were parted, and the complete figure of a thickset priest with a broad, harmless face, his black frock much worn and soiled, stood, bucket in hand, looking at her timidly, and still keeping aloof as he took the path toward the cow in silence.

Romola followed him and watched him without speaking again as he seated himself against the tethered cow and, when he had nervously drawn some milk, gave it to her in a brass cup he carried with him in the bucket. As Romola put the cup to the lips of the eager child, and afterward drank some milk herself, the padre observed her from his wooden stool with a timidity that changed its character a little. He recognized the Hebrew baby, he was certain that he had a substantial woman before him; but there was still something strange and unaccountable in Romola’s presence in this spot, and the padre had a presentiment that things were going to change with him. Moreover, that Hebrew baby was terribly associated with the dread of pestilence.

Nevertheless, when Romola smiled at the little one sucking its own milky lips and stretched out the brass cup again, saying, “Give us more, good father,” he obeyed less nervously than before.

Romola on her side was not unobservant; and when the second supply of milk had been drunk, she looked down at the roundheaded man and said with mild decision, “And now tell me, father, how this pestilence came, and why you let your people die without the sacraments, and lie unburied. For I am come over the sea to help those who are left alive—and you, too, will help them now.”

He told her the story of the pestilence, and while he was telling it, the youth who had fled before had come peeping and advancing gradually, till at last he stood and watched the scene from behind a neighboring bush.

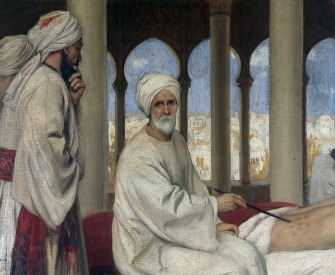

Saint Hedwig washing the feet of lepers, from a Silesian manuscript, 1353. © The J. Paul Getty Museum. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Three families of Jews, twenty souls in all, had been put ashore many weeks ago, some of them already ill of the pestilence. The villagers, said the priest, had of course refused to give shelter to the miscreants, otherwise than in a distant hovel, and under heaps of straw. But when the strangers had died of the plague, and some of the people had thrown the bodies into the sea, the sea had brought them back again in a great storm, and everybody was smitten with terror. A grave was dug, and the bodies were buried; but then the pestilence attacked the Christians, and the greater number of the villagers went away over the mountain, driving away their few cattle and carrying provisions. The priest had not fled; he had stayed and prayed for the people, and he had prevailed on the youth Jacopo to stay with him; but he confessed that a mortal terror of the plague had taken hold of him, and he had not dared to go down into the valley.

“You will fear no longer, father,” said Romola, in a tone of encouraging authority. “You will come down with me, and we will see who is living, and we will look for the dead to bury them. I have walked about for months where the pestilence was, and see, I am strong. Jacopo will come with us,” she added, motioning to the peeping lad, who came slowly from behind his defensive bush, as if invisible threads were dragging him.

“Come, Jacopo,” said Romola again, smiling at him, “you will carry the child for me. See! Your arms are strong, and I am tired.”

That was a dreadful proposal to Jacopo, and to the priest also; but they were both under a peculiar influence forcing them to obey. Their minds were filled with the sense that she was a human being whom God had sent over the sea to command them.

“Now we will carry down the milk,” said Romola, “and see if anyone wants it.”

So they went all together down the slope, and that morning the sufferers saw help come to them in their despair. There were hardly more than a score alive in the whole valley; but all of these were comforted, most were saved, and the dead were buried.

George Eliot

From Romola. This scene takes place toward the end of Eliot’s novel, her only foray into historical fiction, after Romola, having broken with the fanatical Dominican preacher Girolamo Savonarola, flees the turbulence of Florence by drifting out to sea to die. Instead she finds herself on an island where a village of Jews suffering from the plague has been abandoned. The novel was adapted into a successful 1924 silent film starring Lillian Gish in the title role. “Illness seems to me,” Eliot wrote to the women’s rights activist Clementia Taylor in 1852, “the one woe for which there is no comfort—no compensation.”