A college degree is a social certificate, not a proof of competence.

—Elbert Hubbard, 1911Monstrous Errors

Teaching is more than a question of method.

The Rational Education of Children

A league for the rational education of children? But are not the most rational methods for the education of children everywhere applied? Alas! All those who have studied these questions with complete independence of spirit, all those who have observed teachers and pupils, unhampered by preconceived ideas, know that in matters of education and instruction, there is hardly a place where anything is done that ought to be done.

Unluckily, such are very few in number, and that is why the current opinion is that the education of children is one of the domains in which the most has been accomplished. The majority do not know. Some, it must be said, voluntarily deceive themselves as to the value of our present instruction. The latter, however, is almost always merely a facade, a sumptuous and pretentious facade, behind which are hidden lamentable inutilities or monstrous errors.

It will be readily understood that we cannot offer here a complete criticism of the official school, with its overcrowded classes, as at present in operation. Everyone knows that such a quota of pupils is imposed on a single instructor, that the most gifted teacher, armed even with the most intelligent methods and animated with whatever zeal he may have, must confine himself to what is known in professional lingo as “maintaining discipline.”

Almost everywhere the pupils still learn textbooks on grammar, arithmetic, geography, and history by heart. That is to say that the child’s memory exclusively is addressed instead of his intelligence being solicited. Is it necessary to urge the result of such a method?

Hardly ever, even when it would be easy to do, is the living reality approached. Let us suppose ourselves in a village. A few yards from the threshold of the school, the grass is springing, the flowers are blooming; insects hum against the classroom windowpanes; but the pupils are studying natural history out of books!

A graver thing than all the rest: our unfortunate children do not always enjoy the few hours of free recreation necessary to their physical development. Behold them, hardly out of the classroom, hurrying toward the house where they will again sit till evening bent over tasks, three-quarters of which are perfectly useless. It often happens that between the morning and afternoon classes, they do not even have time to eat their meal as they should. Instead we make them learn lessons on the necessity of physical exercise and the hygiene of digestion.

Nor let us forget the question of examinations, that plague of all teaching. In reality the children do not study; they prepare for examinations. It begins among the very little ones, with the certificate for primary studies. Thus the exclusive aim of everyone’s efforts, the teacher’s as well as the pupil’s, is no longer to advance, quietly and surely, in the discovery of new facts and truths, but on a fixed date, to have handed out—all means being allowable, provided they lead to success—a certificate of knowledge. They are content with the sign; the thing itself is held cheap.

It must be admitted that almost the sole preoccupation is to furnish the pupils certain information, judged, no one knows very well why, to be indispensable. Without, moreover, succeeding in it! Has not a recent sensational inquiry proved that in a little while after quitting school, almost nothing of what it was believed had been put there remained in the brains of our French youth?

Even if our children retained all that it has been decided on high they ought to know, it would prove little in favor of such teaching as is done today. Relatively to the present total of knowledge, the school can teach but a ridiculously small fraction of this knowledge. School is kept, on the contrary, in order to give the pupil the means of acquiring knowledge and the taste for it, that is to say, in order to fortify his intelligence, to provide him with a sure logic, indispensable instruments for study, and also to interest him in all possible manifestations of human activity.

Whether you teach history or agriculture, literature or chemistry, arithmetic or geography, you can do it in two ways: in a way to fortify the judgment or to falsify and atrophy it in the germ; the way that will attach the pupil always to the order of knowledge that you will open to him for the first time or that which will disgust him with it forever. The school fails in its essential function if it does not inculcate in the child an enthusiastic love of life and of humanity. It is from this standpoint that it should establish contact between knowledge and the child.

Each branch of knowledge provokes its particular emotion, its special interest. To arouse these different sorts of interest or emotion in the child, to arrange all so that these successive “initiations” may take place under the best possible conditions, such should be the first and constant care of the master.

Such are, but too briefly indicated, the essential ideas that our league wishes to defend and to propagate everywhere.

The School and Neutrality

At the moment when the clericals seem to want to resume the old battle against the secular school, at the moment in which discussions about the neutral school are beginning again, we shall surely be asked what attitude we intend to take in the presence of the child concerning the great religious, philosophical, political, and social problems that agitate the present hour. We might declare that we are pedagogues first of all, confining ourselves to the investigation of good methods of teaching. But we shall not make this reply, because there is something more in teaching than a question of method. And that is why “neutrality in the school” can be nothing but hypocrisy.

Let us suppose that we have succeeded in expurgating programs and manuals of all embarrassing questions. Can we prevent the episodes of social life from putting the same questions, in the form of naive interrogatories, into the little ones’ mouths every day? Can we prevent war, crime, rioting, strikes, assassinations, poverty? And when these “embarrassing questions” have once risen to the child’s lips, can we give any other answer than that which our conscience dictates, cries to us?

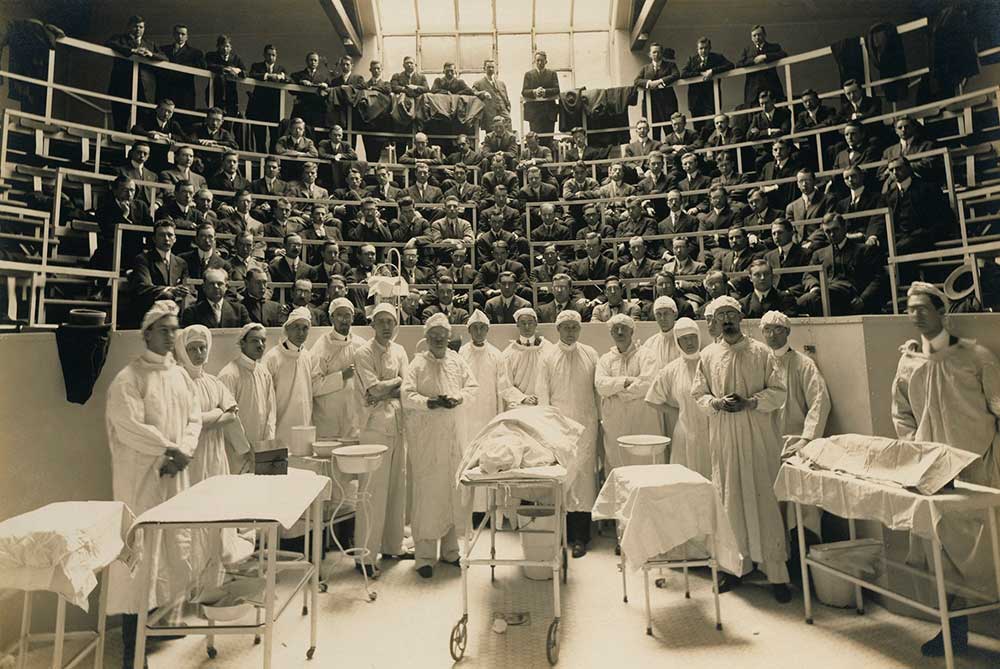

Medical school class and staff with cadaver, c. 1900. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

There is no good “neutral instruction,” because all good teaching presupposes force, warmth, conviction. The ardent, the enthusiastic, and the generous soul of the child needs an atmosphere of conviction and enthusiasm. The educator should not dissimulate his philosophical and social preferences. We should not hide the fact that we are democrats, socialists, and atheists in the fullest and highest sense of these words. We should not, in the school, hide the fact that we want to develop in the children such an eagerness to live, such a confidence in life, such an interest in terrestrial realities, that there would soon remain no place for dreams about the beyond. We should not, in the school, hide the fact that we would awaken in the children the desire for a society of men truly free and truly equal, equal economically as well as politically, and hence of real solidarity; a society without violence, without hierarchies, and without privilege of any sort.

But in our so legitimate desire to form the young generations for the conquest of liberty and social equality, we must not forget that we have no right to impose this ideal on the child, however beautiful and true it may be. Let us not take advantage of the fact that he is almost without defense against our assertions to make him admit, whatsoever it may be, without making him understand it. It is not a matter of substituting one dogma for another dogma, one catechism for another catechism. In this as in all other things, let us try not to have the child recite his lesson coldly but to have him really perceive, feel, and understand the utility and the grandeur of the aim sought. Let us try to awaken his conscience, interest his instinct of justice, enkindle his courage and his pride. Let us remember that our first care should be to prepare for life healthy and robust beings, beings conscious and clear-minded, endowed with a critical spirit, capable of discerning and deciding for themselves; and that it is thus that the school will labor most surely for human emancipation.

And above all, let us not forget that in matters of education, there is but one right superior to all others and before which all others should yield: the right of the child.

About This Text

From the manifesto of the International League for the Rational Education of Children. The anarchist educator Francisco Ferrer founded the coeducational Modern School in Barcelona in 1901. He was forced to close it five years later when he was imprisoned for trying to assassinate Alfonso XIII. After his release, he moved to Paris and established the International League, declaring, “There should be nothing more free and supple, less regulated in advance, than school life.” An English translation of this manifesto appeared in Emma Goldman’s magazine Mother Earth.