Do you suppose it possible to know democracy without knowing the people?

—Xenophon, 370 BCElectoral Tampering

A Korrygram on a closely watched election.

Chile voted calmly to have a Marxist-Leninist state, the first nation in the world to make this choice freely and knowingly.

Dr. Salvador Allende proved the wisdom of Soviet policy in Latin America by scoring the revolutionary tactic of his model, Fidel Castro, to pursue an electoral path to power. His margin is only about 1 percent, but it is large enough in the Chilean constitutional framework to nail down his triumph as final. There is no reason to believe that the Chilean armed forces will unleash a civil war or that any other intervening miracle will undo his victory. It is a sad fact that Chile has taken the path to communism with only a little more than a third (36 percent) of the nation approving this choice, but it is an immutable fact. It will have the most profound effect on Latin America and beyond; we have suffered a grievous defeat; the consequences will be domestic and international; the repercussions will have immediate impact in some lands and delayed effect in others.

We have been living with a corpse in our midst for some time, and its name is Chile. The decomposition is no less malodorous because of the civility that accompanies it. Chileans could as usual chatter endlessly on television and radio and in the early hours today as if nothing had changed and the screen switched from variety shows to roundtables of politicians pontificating as foolishly as ever. Chileans like to die peacefully with their mouths open.

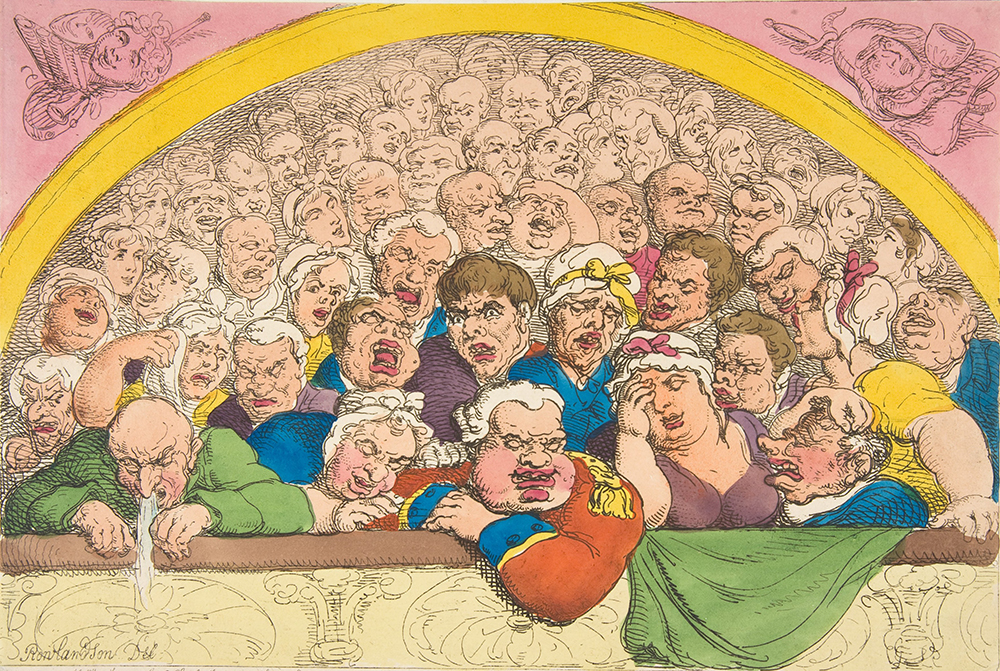

Pidgeon Hole: A Convent Garden Contrivance to Coop up the Gods, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1811. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

Preliminary analysis of the results (I write this with votes still to be counted, but the stink of defeat is evident, and the mounting roar of Allendistas acclaiming their victory arises from the streets below) show that Allende got every bit of the 35 percent we had feared plus more women in the low-income neighborhoods. He also benefited from the switch in Santiago of middle-class women from the aging Alessandri to the prattling Tomic. In their majority the females opted for law and order as represented by Alessandri, but enough thought they had nothing to lose with Allende, and others were seduced by the lure of the center where Tomic stood.

Allende did not equal his 39 percent of 1965. He did not come close to the 46 percent that was the sum of the parties that formed the Popular Unity. It is obvious that the clientele of the Radical Party deserted him in droves. But it is equally evident, as I wrote on election eve, that 65 percent of Chile is anti-Right, and Alessandri was so identified with that position that he could gain the predictable 5 percent minimum and no more.

There were no surprises in the yearlong campaign, no sudden “events” that affected voters’ decisions. We erred by 1 percent on Allende, predicted the Tomic vote, and were only 2.5 percent off on the Alessandri prediction. But the Communist Party, whose leadership has been matched by the coldness of its calculations, predicted the Allende vote as 36 percent and the Alessandri tally as 4 percent. They were almost dead on target. If anyone thinks that such a party will not fully exploit the Allende presidency to impose on Chile a communist structure, I suggest they ponder the dead reckoning of these cool customers.

I have confessed repeatedly in these communications my equal distrust of a Right that blindly and greedily pursued its interests, wandering in a myopia of arrogant stupidity. They disdained organization and deliberately scorned the one element of their forces that had some semblance of structure, the National Party. They preached vengeance against the Christian Democrats, whom they regarded as a more justifiable enemy because of its betrayal of class than their class enemy, the Communists. They fought the first rule of nature, of change, and insolently believed that time stands still. They only tolerated the few modernists in their midsts, men who were certainly no less rich, no less self-interested, but who at least understood the flux in which we are all caught.

Allende was smarter. He was persuaded by the Communists to stick to bread-and-butter issues, to project a personality with broader appeal than a rigid and cynical doctrinaire. With 60 percent of Chile still poor and with inflation and unemployment the rock-bottom electoral issues, it is truly surprising that only 36 percent voted for him.

We, too, were misled by the polls I have so often mocked. The Gallup and much-respected CESEC polls were way off the beam. They predicted 41.5 percent for Alessandri, and although the embassy calculated an actual vote of 36.5 percent for Alessandri, I was enough influenced by these foolish samplings to increase the projection to 38 percent. Voters are not Gadarene swine; in a society with 90 percent literacy, they can be quite bloody-minded about their interests. And when the candidate of the government party preaches that the system in which they live is rotten and issues the call for revolution, it is not surprising that enough decide to place their faith in the genuine article.

Edward Korry

From diplomatic cables to the U.S. Department of State. A onetime European editor at Look magazine, Korry was U.S. ambassador to Chile from 1967 to 1971. The United States supported the 1973 coup d’état that overthrew duly elected president Salvador Allende and resulted in the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. According to the BBC, more than three thousand people were killed under Pinochet’s regime, with over a thousand others unaccounted for. Korry, who died in 2003, claimed he knew nothing of the CIA plot to stage the military takeover.