December 27

I went to visit Sir John Chardin, a French gentleman, who traveled three times by land into Persia and had made many curious researches in his travels, of which he was now setting forth a relation.

It being in England this year one of the severest frosts that has happened of many years, he told me the cold in Persia was much greater, the ice of an incredible thickness, that they had little use of iron in all that country, it being so moist (though the air admirably clear and healthy) that oil would not preserve it from rusting, so that they had neither clocks nor watches; some padlocks they had for doors and boxes.

January 1, 1684

The weather continuing intolerably severe, streets of booths were set up on the Thames. The air was so very cold and thick, as of many years there had not been the like. The smallpox was very mortal.

January 6

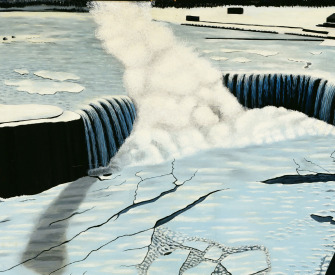

The river quite frozen.

January 9

I went across the Thames on the ice, now become so thick as to bear not only streets of booths, in which they roasted meat and had divers shops of wares, quite across as in a town, but coaches, carts, and horses passed over. So I went from Westminster stairs to Lambeth and dined with the archbishop, where I met my Lord Bruce, Sir George Wheeler, Colonel Cooke, and several divines. After dinner and discourse with His Grace till evening prayers, Sir George Wheeler and I walked over the ice from Lambeth stairs to the Horseferry.

January 24

The frost continues more and more severe, the Thames before London was still planted with booths in formal streets, all sorts of trades and shops furnished and full of commodities, even to a printing press, where the people and ladies took a fancy to have their names printed and the day and year set down when printed on the Thames. This humor took so universally that it was estimated that the printer gained five pounds a day for printing a line only, at sixpence a name, besides what he got by ballads, etc. Coaches plied from Westminster to the Temple, and from several other stairs to and fro, as in the streets, sleds, sliding with skates, a bullbaiting, horse and coach races, puppet plays and interludes, cooks, tippling, and other lewd places, so that it seemed to be a bacchanalian triumph, or carnival on the water, while it was a severe judgment on the land, the trees not only splitting as if the lightning struck but men and cattle perishing in divers places, and the very seas so locked up with ice that no vessels could stir out or come in. The fowls, fish, and birds and all our exotic plants and greens universally perishing. Many parks of deer were destroyed, and all sorts of fuel so dear that there were great contributions to preserve the poor alive. Nor was this severe weather much less intense in most parts of Europe, even as far as Spain and the most southern tracts. London, by reason of the excessive coldness of the air hindering the ascent of the smoke, was so filled with the fuliginous steam of the sea coal that hardly could one see across the street, and this filling the lungs with its gross particles exceedingly obstructed the breast so as one could scarcely breathe. Here was no water to be had from the pipes and engines, nor could the brewers and divers other tradesmen work, and every moment was full of disastrous accidents.

Thunderstorm and Fleeing Horsemen, Flemish School, seventeenth century. © Cameraphoto Arte, Venice / Art Resource, NY.

February 4

I went to Sayes Court to see how the frost had dealt with my garden, where I found many of the greens and rare plants utterly destroyed. The oranges and myrtles very sick, the rosemary and laurels dead to all appearance, but the cypress likely to endure it.

February 5

It began to thaw but froze again. My coach crossed from Lambeth to the Horseferry at Milbank, Westminster. The booths were almost all taken down, but there was first a map or landscape cut in copper representing all the manner of the camp, and the several actions, sports, and pastimes thereon, in memory of so signal a frost.

From his diary. The winter of 1683–84, said to be the most severe in England’s history, brought with it the most celebrated of the Thames’ “frost fairs,” held sporadically from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Evelyn, a country gentleman, kept a diary spanning over seven decades that contains valuable insight into seventeenth-century English society. An enthusiast of gardening and forestry, he designed several pleasure gardens, including a famed garden at Sayes Court. “We will endeavor to show,” he wrote to Thomas Browne, “how the air and genius of gardens operate upon human spirits toward virtue and sanctity.”

Back to Issue