Interviewer: Mr. Berryman, recognition came to you late in comparison with writers like Robert Lowell and Delmore Schwartz. What effect do you think fame has on a poet? Can this sort of success ruin a writer?

John Berryman: I don’t think there are any generalizations at all. If a writer gets hot early, then his work ought to become known early. If it doesn’t, he is in danger of feeling neglected. We take it that all young writers overestimate their work. It’s impossible not to—I mean if you recognized what shit you were writing, you wouldn’t write it. You have to believe in your stuff—every day has to be the new day on which the new poem may be it. Well, fame supports that feeling. It gives self-confidence, it gives a sense of an actual, contemporary audience, and so on. On the other hand, unless it is sustained, it can cause trouble—and it is very seldom sustained. If your first book is a smash, your second book gets kicked in the face, and your third book, and lots of people, like Delmore, can’t survive that disappointment. From that point of view, early fame is very dangerous indeed, and my situation, which was so painful to me for many years, was really in a way beneficial.

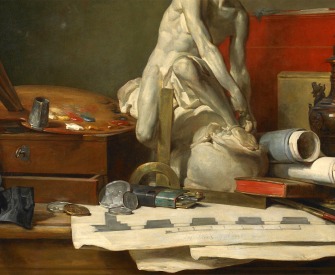

Sultan Süleyman I, Emperor Charles V, King Francis I, from Marriage at Cana (detail), by Paolo Veronese, c. 1562. Louvre Museum, France.

I overestimated myself, as it turned out, and felt bitter, bitterly neglected. But I had certain admirers, certain high judges on my side from the beginning, so that I had a certain amount of support. Moreover, I had a kind of indifference on my side—much as Joseph Conrad did. A reporter asked him once about reviews, and he said, “I don’t read my reviews. I measure them.” Now, until I was about thirty-five years old, I not only didn’t read my reviews, I didn’t measure them, I never even looked at them. That is so peculiar that close friends of mine wouldn’t believe me when I told them. I thought that was indifference, but now I’m convinced that it was just that I had no skin on—you know, I was afraid of being killed by some remark. Oversensitivity. But there was an element of indifference in it, and so the public indifference to my work was countered with a certain amount of genuine indifference on my part, which has been very helpful since I became a celebrity. W.H. Auden once said that the best situation for a poet is to be taken up early and held for a considerable time and then dropped after he has reached the level of indifference.

Something else is in my head: a remark of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges. Two completely unknown poets in their thirties—fully mature—Hopkins, one of the great poets of the century, and Bridges, awfully good. Hopkins with no audience and Bridges with thirty readers. He says, “Fame in itself is nothing. The only thing that matters is virtue. Jesus Christ is the only true literary critic. But,” he said, “from any lesser level or standard than that, we must recognize that fame is the true and appointed setting of men of genius.” That seems to me appropriate. This business about geniuses in neglected garrets is for the birds. The idea that a man is somehow no good just because he becomes very popular, like Robert Frost, is nonsense, also. There are exceptions—Thomas Chatterton, Hopkins, of course, Arthur Rimbaud, you can think of various cases—but on the whole, men of genius were judged by their contemporaries very much as posterity judges them. So if I were talking to a young writer, I would recommend the cultivation of extreme indifference to both praise and blame because praise will lead you to vanity, and blame will lead you to self-pity, and both are bad for writers.

From “The Art of Poetry No. 16” in The Paris Review. While on a fellowship at Cambridge University in the late 1930s, Berryman met, among other poets, W.H. Auden and W.B. Yeats. He published Poems in 1942, the biography Stephen Crane in 1950, and Homage to Mistress Bradstreet in 1956. At the age of fifty-seven in 1972, Berryman committed suicide by jumping off a bridge onto the ice of the Mississippi River.

Back to Issue