In his latest published book, Mr. Magister S. Kierkegaard has announced that the following pseudonymous authors are one and the same person and that this one person is he himself, Søren Kierkegaard, namely: Victor Eremita, Johannes de Silentio, Constantin Constantius, Vigilius Haufniensis, Nicolaus Notabene, Johannes Climacus, Hilarius Bookbinder, William Afham, the judge, and—Frater Taciturnus.

We wonder how the public feels about such a cloudburst of authors. This is the way the snow melts on the mountaintops in the spring; every single snowdrift is dissolved and all flow together into one single, great, foaming, violent mountain torrent, and this mountain torrent is Søren Kierkegaard, the one and only, and the startled public stares at his mighty dialectical leap.

Mr. Kierkegaard uses this occasion also to comment on praise and censure. He does not wish to be praised, it is an inconvenience to him; for him it is the same as when someone takes off his hat to him on the street and then he has to remove his hat, and he would rather not do that. But then one would think that he would tolerate censure so that he could let his hat sit in peace—but he does not want that, either. He “thanks everyone who has kept silent,” but he thanks Bishop Mynster, because he has praised him. Consequently, he does not want censure in any form; Bishop Mynster has a monopoly on praising him, and anyone who interferes with that privilege will be subpoenaed and fined heavily. Consequently, all the rest of us should keep our mouths shut.

It is really strange that a man does not have control of the book he buys and pays for with three rix-dollars and sixty-four shillings. If Magister Kierkegaard invites a man to his home and gives him a cup of coffee and says to him, Here you will taste the best coffee you have ever tasted in your life. But you must be absolutely dumb with ecstasy, you must not praise it; the only one who has permission to praise my coffee is Bishop Mynster. Neither must you find any fault with it, for then I will kick you down the stairs—then Mr. Kierkegaard, MA, is within his rights. If the man refuses to accept the terms, he does not get the coffee. Likewise, if Mr. Kierkegaard, MA, has a book printed for private circulation among his friends and gives it away, then he can request first of all, Do you acknowledge this book to be perfect, so pure and sensitive that the mere breath of human judgment defiles it? If the man swears a sacred oath on that, he gets the book, bound in morocco with gilded edges, under the pain of ostracism and perpetual silence. But, when one has honestly and uprightly paid his three rix-dollars and sixty-four shillings and then is told, Read it as you read the Bible; if you do not understand it, then read it over again; if you do not understand it the second time, you may just as well blow your brains out—then a strange feeling comes over one. There is a moment when his mind is confused and it seems to him that Nicolaus Copernicus was a fool when he insisted that the earth revolves around the sun; on the contrary, the heavens, the sun, the planets, the earth, Europe, and Copenhagen itself revolve around Søren Kierkegaard, who stands silent in the middle and does not once take off his hat in recognition of the honor shown to him.

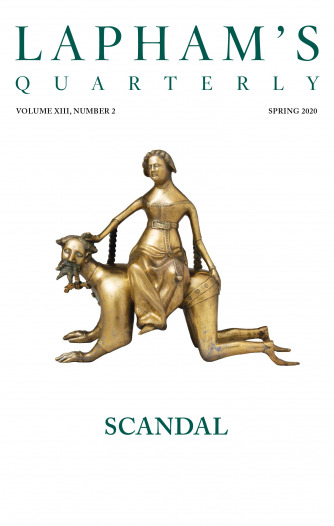

Apotheosis of Napoleon III, by Guillaume-Alphonse Harang Cabasson, 1854. Musée Compiègne, France.

“Who, what, then, is this Søren Kierkegaard?” thousands are certainly asking who have heard mention of him and his enormous books.

Magister artium Søren Kierkegaard, ladies and gentlemen, is a man with two legs like all the rest of us. As far as his activity—partly as a man, partly as a writer—is concerned, this can best be illustrated by an example. He comes walking along Gothersgade, for example, and a man falls and breaks his leg outside the vegetable store, where a woman recently was injured. The magister stops momentarily and observes: (1) the man’s scream and the surprise clearly portrayed on his face as he falls, (2) his shock when he gets up and notices that his own leg is not functioning because it is broken, (3) the pain in his leg that drives all other expressions from his face. This was the time to step in and help the man, if the second stage of the observation did not intervene: (1) the comic busyness and primness of the people hurrying by, (2) their various questions to the suffering man and their arguing with one another about how he is to be taken away, (3) their cursing at the street commissioners and the property owners for not spreading ashes on the sidewalk. When the observation is finished, the magister goes home to record the results. You reconcile yourself to him; you expect that now he either will make himself useful to society by writing an article to Politivennen about the slippery sidewalks or entertain society with a beautiful and poetic portrayal of misfortune, suffering, death, resurrection, or the like. By no means, he goes home and writes thusly: “If the speculative thinker explains the paradox in such a way that he canceled it and now consciously knows that it is canceled, that consequently the paradox is not the eternally necessary relation of eternal truth to an existing person in the extremities of existence, but only an accidental relation to limited minds—then there is an essential difference between the speculative thinker and the simple man, whereby all existence is fundamentally confused.”

Reader, he really did say this about poor minds in his latest book, p. 168—but you easily perceive that it could just as well be said about poor legs.

©1982 by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Used with permission of the Princeton University Press.

From an article published in The Corsair. Møller questioned Kierkegaard’s talent in an article published the previous year, setting off a war of words between the satirical paper and the philosopher that lasted until 1847. In the last decade of his life, Kierkegaard attacked the Church of Denmark in various writings, declaring the need to “introduce Christianity into Christendom.” He died at the age of forty-two in 1855.

Back to Issue