War is sweet to those who don’t know it.

—Erasmus, 1508

A composite image of Kaiser Wilhelm II and his Generals, c. 1914. United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., the George Grantham Bain Collection.

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

—Leo Tolstoy

The great French historian and resistance martyr, Marc Bloch, is supposed to have said that history was like a knife: You can cut bread with it, but you could also kill. This is even more true of historical derivatives like analogies; they can provide either illumination or poisonous polemic. The first requirement for an acceptable historical analogy is plausibility; the two situations compared must have striking similarities, and the image of the historic antecedent must be as clearly understood as possible. This becomes an unlikely presupposition when the analogy is proposed by partisans working in an age of stunning historical ignorance. Nowadays, politicians and partisans use analogies instead of arguments, convenient shorthand for their defenses of dubious policies.

It was beneficial that President Kennedy was conscious of historical analogies. During the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, he remembered how easily nations had slipped into World War I in 1914, and how important it was to give an adversary a chance to back down while saving face. When the invasion of Cuba was being considered, he noted to Robert McNamara, “It seems to me we could end up bogged down. I think we should keep constantly in mind the British in the Boer War, the Russians in the last war with the Finnish, and our own experience with the North Koreans.” But it was dangerously misleading in 2003 to brandish comparison of the Allied occupations of Germany and Japan in 1945 with the American occupation of Iraq solely in order to suggest the ease of establishing democracy by force of arms.

The Devil and the good man may cite Scripture—for opposite purposes. This is true for analogies as well. Some historic moments or persons may be unique—try to find another Abraham Lincoln, for example. Even Iagos are hard to come by. It may be proper to recall Jacob Burckhardt’s warning-cum-aspiration: Our study of history will not make us clever for the next time but should make us wise forever.

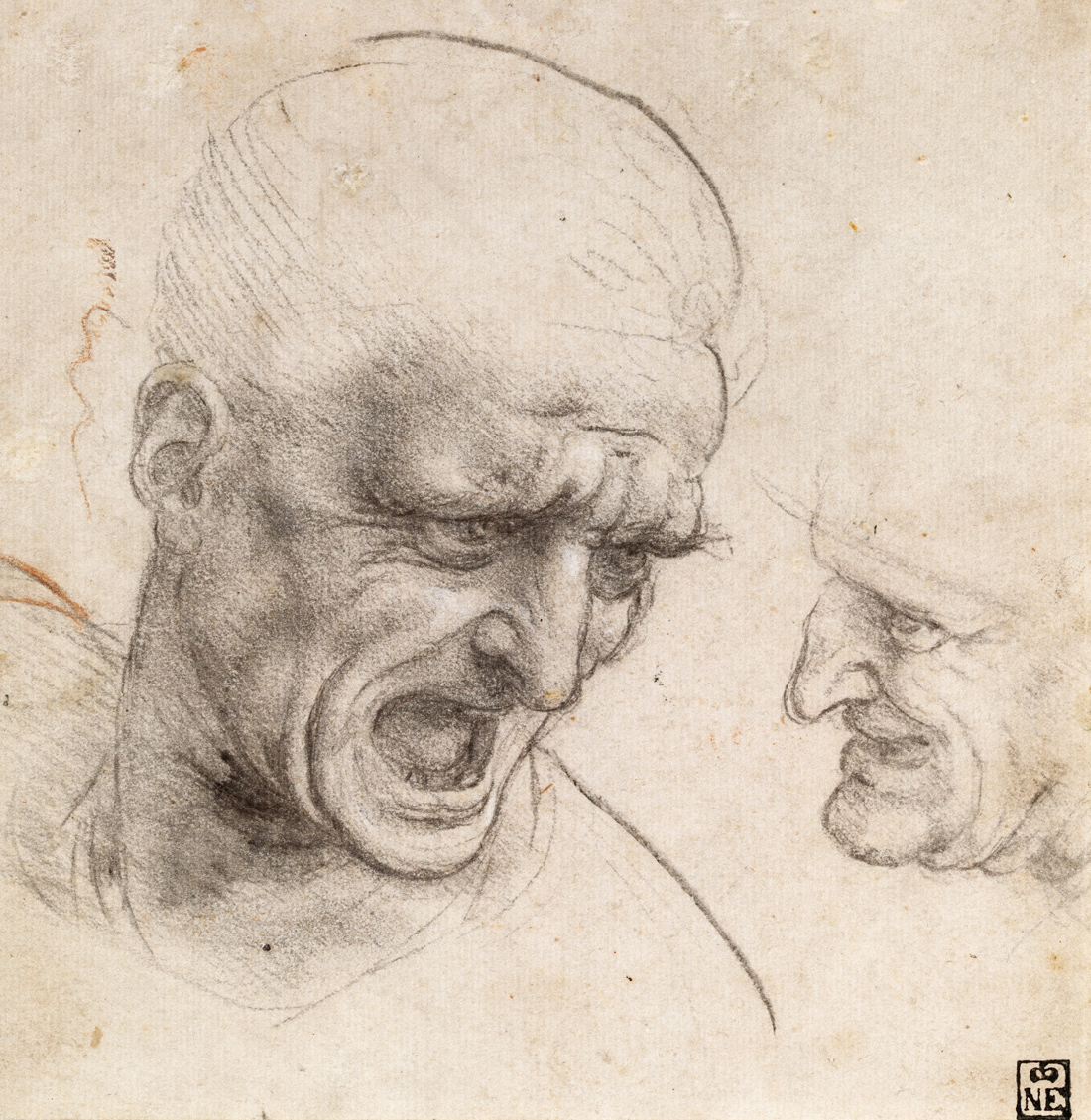

Study of Two Warriors’ Heads for the Battle of Anghiari, by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1504. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary.

The United States, with its frequent claim of exceptionalism, should be free of historical analogies, and at the time of the American Revolution, the struggle to establish a constitutional republic was without modern parallel. But as the nation became a world power and, finally, the world power, its boast of exceptionalism began to sound hollow, and comparisons with the fate of earlier empires became common.

With the defeat of the Axis powers in 1945, the United States emerged as the leading power of the West, and was thereafter confronted by imperial responsibilities and temptations. At home, the “Red Scare” became a powerful political-psychological force. Abroad, the successive burdens of Korea and Vietnam, which demanded the sacrifice of American lives and fortunes, were followed by the rise of an altogether new challenge, international terrorism, with the United States as its principal target.

A nation puzzled and divided by American ascendancy following World War II was attuned to the many analogues that politicians and partisan scholars offered. It is no wonder many of these analogies focused on the most dramatic and recent world-historical disaster—the rise and fall of Hitler and his empire. In the early 1950s, left-wing alarmists saw in Senator McCarthy a Hitler and in Eisenhower, a Hindenburg. At the time, I thought this an invidious and dangerous comparison in that American political culture was fundamentally different from that of Germany. But German has been the language of politics in extremis, Weimar the symbol of democratic self-destruction, Hitler the reminder of the all-powerful, enthralling tyrant—and appeasement of him as the road to war.

Perhaps no single analogy has been so often and so perniciously invoked as “Munich.” (How many remember what actually happened?) The Munich Conference of September 1938 was the culmination of Anglo-French attempts to anticipate or accept Hitler’s demands, to recognize the “injustices” visited upon Germany at Versailles, and to make efforts above all to avoid another war. Some proponents of appeasement—members of the ruling classes, ill-guided conservatives who hoped to preserve their own power—may have had a sneaking admiration for the decisive leader as the great anti-Bolshevik shield. Meanwhile, the European left and a few realistic conservatives (Winston Churchill is the heroic example) insisted that Hitler aimed for European hegemony and that only resolute will and the threat of force could stop him. To label American critics of an escalating involvement in Vietnam or Iraq as “appeasers” or proponents of “Munich” is dangerous nonsense, all the more so because the analogy may obscure the actual dangers that confront the United States.

I have been struck recently by an altogether different analogy from the drama of German history, namely the disaster and political fatality of German leadership during World War I, epitomized by the supreme leader of the time, Kaiser Wilhelm II. The Kaiser came to the throne in 1888 at the age of twenty-nine, his liberal father having reigned—voicelessly—for ninety-nine days before succumbing to cancer of the throat. The young Kaiser’s grandfather, Wilhelm I, a true Prussian monarch, had presided over the military victories that had enabled Bismarck to create the unified Reich in 1871. Within two years of his ascension to the throne, Wilhelm II dismissed Bismarck—the nation’s later idol, a prudent diplomat in European affairs, and a fierce enemy of democratic reform at home.

Wilhelm II became the leader of a country that was on the cusp of European mastery. By the 1890s imperial Germany had become the strongest power on the continent, strongest in economic and military terms and equal or superior to all in scientific and technological advances. But power generates opposition, and Germany’s neighbors, alarmed at this unpredictable upstart, began to form defensive alliances against it. Supreme prudence would have been required on Germany’s part to meet these challenges, but Wilhelm sought to incarnate that power in his person and to concentrate it within his conflicted self. He appeared on the world stage as a boisterous and threatening leader, while at home he flaunted his absolute power, believing that it had been divinely ordained. He had contempt for a parliament whose tightly circumscribed powers were set forth in a constitution he boasted of never having read. He was intelligent, perhaps even gifted, and impressed by technological progress, but untutored and impulsive. He reveled in the trappings of power and delighted in uniforms (at times he changed them daily). In his ostentation and extravagance, he was deeply un-Prussian. He was the perfect parvenu of ancient plumage, and he both reflected and reinforced the proud, ambitious, yet fearful character of his subjects. Given his position in Europe—not nearly as hemmed in politically as his royal cousin in Britain, King George V, and not nearly so absolute in his rule as his Russian cousin, Tsar Nicholas II, over a far less developed country—he was unique, and hence his deeply complicated character is an attractive object for historians. Recently published evidence derived from wartime diaries and letters of his closest associates powerfully amplify our picture of the emperor and his private flaws that so decisively deformed his public policy.

He was given to bombastic speeches, once warning newly sworn-in recruits that, if ordered by him, they would have to shoot their parents. He gave astounding orders to departing soldiers at the time of the Boxer Rebellion that they should arouse fear as had the Huns of yore. He detested liberal critics. And he spoke disparagingly of foreign nations, especially of Great Britain. Some of this had to do with his Anglophobia; he totally distrusted his mother, the daughter of Queen Victoria. Worse, though, than his arrogant, bombastic statements, he supported ministers and military personnel who called for an ever greater German army—and, most ominously—for a high seas fleet that would eventually be strong enough to defeat the British navy. The details of government he shunned, for they interfered with his diversions. He wanted to reign, and he enjoyed his huge court—over two thousand subordinates from generals to servants to gardeners, whom he would at times affront with crude jokes and offensive pranks.

From the beginning, members of his entourage and some cognoscenti worried about his volatility and mental health. He had suffered an extremely complicated birth, and moments of oxygen deprivation may have damaged his brain. As a youth, he contracted a chronic middle-ear infection that some people wrongly thought could induce mental imbalance. Others saw mere tactlessness bolstered by boundless vanity. Some of his immediate subordinates made harsher judgments. Thus Admiral Tirpitz—fateful champion of the all-powerful navy—thought that Wilhelm compensated for his inner uncertainty and insecurity with pomp and militant rhetoric. Brutal virility was a central feature of Wilhelm’s persona. In 1903, Tirpitz further noted, “The sad and worrisome thing about this talented monarch is that for him appearance trumps substance.”

German foreign policy from 1890 to 1914, for which the Kaiser bore formal and—intermittently—actual responsibility, culminated in a series of failures and setbacks. Many blamed these gratuitous blunders on Wilhelm’s capriciousness and desire for prestige, his concern for dynastic and personal vanity, and his failure to assess Germany’s true national interests. A strident militaristic tone prevailed, supported by well-organized interests who saw economic benefits in greater armaments. These “lobbyists” thought foreign triumphs a protection against democratic political reforms at home, which posed an ominous threat to the anachronistic power of what has often been called an agrarian-industrial-military complex. Max Weber, a passionate advocate of Germany’s worldwide ambitions and responsibilities, noted in 1906, “The degree of contempt that our nation increasingly encounters abroad (Italy, America, everywhere!)—and with justice—is the decisive issue. Our submission to this regime of this man is gradually becoming a power issue of ‘world’ importance to us.…We are becoming ‘isolated’ because this man rules us in this way and because we tolerate it and make excuses for it.” (Emphasis added.) This was not an uncommon view among true conservatives, although in Weber’s case, it was voiced only in private correspondence, becoming public only after a particularly egregious interview the Kaiser gave to the Daily Telegraph in 1908.

And yet they were wrong, at least in part. Wilhelm’s rule was not absolute, as Germany’s conduct during World War I made clear. In early July 1914, after the murder of the Austrian archduke, the Kaiser egged on the Austrians. By the end of the month, he couldn’t restrain his own subordinates from beginning a war according to the dictates of military strategy—the famed Schlieffen Plan—rather than political rationale. Once war had started, Wilhelm became Supreme War Lord, and his chief function should have been to adjudicate among rival elements in his government. Instead, the civilian-military conflict deepened. The German army always had a state-within-a-state mentality, and, in this case, both the military and the civilian leaders were divided among themselves.

After a proclamation exalting national unity—rallying the innocent nation in the face of foreign attacks—Wilhelm established himself at Supreme Headquarters away from Berlin. Although geographically closer to the front, he was comfortably distant in every other respect. He was more than ever dependent on the heads of his military and civilian cabinets. (Their diaries and letters have been published recently.) By the end of September 1914, after the First Battle of the Marne and the failure of the Schlieffen Plan, some of his advisers realized that the chances for a military victory were slim and argued the need for a negotiated peace. But by that time, even the civilian chancellor had committed to extravagant war aims that made hopes for a negotiated peace illusory. The head of the military cabinet, the ultraloyal General Hans Georg von Plessen, noted that, “The Kaiser was again at lowest point with his nerves, without faith in the future, without self-confidence.”

From then on, the Kaiser’s ever shifting mental state became a dominant issue in the conduct of the war. Publicly he enunciated his faith in total victory, but privately, he suffered moments of distressed indecision. Publicly he proclaimed the nation’s innocence while privately he condoned German atrocities committed in Belgium. Portentous decisions had to be made, including whether to declare unrestricted submarine warfare, thereby insuring the entry of the United States into the war. Although the fate of his country (and of Europe) depended on how he made these decisions, the Kaiser was only intermittently informed, as his advisers systematically shielded him from bad news. In June 1917, General Plessen noted, “Everything unpleasant is repressed and everything propitious is enormously exaggerated. This ostrich style he calls optimism, and anyone who doesn’t cooperate in this self-deception, he calls a pessimist. Never once during this entire war did he ask even with a syllable about our own losses.” At the same time, the Kaiser regarded the war as a struggle between good and evil, light against darkness: “God wants this struggle and we are His instruments,” he said.

After three years of unimaginable carnage, Wilhelm had been reduced to an instrument of a military dictatorship run by Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff, whom he had been forced to appoint and whose virtually unlimited power rested on their ever present threats of resignation. They enjoyed the confidence of Germany’s ruling classes and were determined to reject all compromise, always putting their faith in one more push that would deliver the ever elusive goal of total victory. Moderate conservatives were ardent in their concern for their country, whose people grew ever hungrier and ever more desperate for an end to the slaughter. A new political force, the Fatherland Party, clamored loudly and successfully for total victory, while thundering at the same time against “internal enemies.” They vilified critics of wartime policies as subversives aiding the enemy. Among such blatant jingoism, anti-Semitism grew exponentially. The Social Democrats were split between the old, stolid group that still hoped for gradual political reform and the newly formed “Independent Socialists” who demanded an immediate end to the imperialist war.

Meanwhile the Kaiser, the putative Almighty or Allerhöchster, as he was called, continued to be shielded from the truth and became further estranged from reality because his immediate circle feared his nervous collapse. As General Plessen framed it, “The Emperor needs the sun.” And so he was protected as much as possible from all darkness, a feat facilitated by his own faith in his infallibility; after all, he was God’s instrument, so providence exculpated him. In this, too, he epitomized his nation; though Wilhelm’s self-delusion was sui generis, the delusion of his people was carefully controlled by official mendacity and repression, the more effective for being largely concealed. All the belligerent nations trimmed the truth, but none as devastatingly successfully as Germany under Hindenburg and Ludendorff.

Scotland For Ever’; The Charge of the Scots Greys at Waterloo, June 18, 1815, by Elizabeth Butler, 1881. Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, West Yorkshire, England.

For the Kaiser, diversions would at times take the place of reality. The ever-loyal chief of the military cabinet, Moritz Freiherr von Lyncker, noted in May 1917, “It is unfortunately true that he disconnects himself from many things and prefers his comfort to all else. He has always been like this, even before the war. He is, after all, very weak, and strong only in protecting his personal private interests, above all an easy and as much as possible undisturbed existence... He isn’t up to the great task—neither with his nerves nor with his intellect.”

For a fleeting moment in the spring of 1918, after the Bolsheviks had signed a German-dictated Carthaginian peace, a German victory seemed as possible as it had in August 1914. But by August 1918, Allied forces had broken through German lines, and a stunned Ludendorff, fearing a sudden collapse of his army, demanded that the newly constituted civilian government send an immediate request to President Woodrow Wilson for an armistice. Wilson responded that the Allies wouldn’t negotiate with the Kaiser. Negotiations dragged on while the hungry, war-weary Germans began to demand the Kaiser’s abdication. At first he refused. “I have no intention of abandoning my throne because of a few hundred Jews, a few thousand workers,” he said on November 3, 1918, as Germans took to the streets in pent-up fury.

The Kaiser finally went into exile in the Netherlands—not by his will, but because the army leaders insisted that he go. As he left, he blamed “Ludendorff, Bethmann, and Tirpitz for having lost the war,” a triumvirate itself consumed by hatred of one another. Until his death in exile in 1941, the Kaiser spread venomous poison where he could: The Jews were to blame, as were the socialists—he alone was right. Reflecting and encouraging the sentiments of all too many Germans, he saw in Hitler the new man chosen by providence, a savior after the treachery that had caused Germany’s defeat.

The Kaiser, long the Allies’ favorite symbol for German arrogance and aggression—as he was for many Germans—came to be regarded as the chief villain of the Great War. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George waged his 1918 election campaign with the slogan “Hang the Kaiser.” Wilhelm had his terrifying flaws, and he operated at the head of a deeply flawed political system. But ultimately his chief failure had been to abandon his responsibility and to yield power to military and civilian hawks—wrongly called conservatives, for their vision was a radical reordering of Europe’s state system. The true villains, Ludendorff and his Pan-German allies, aimed at nothing less than world hegemony while Wilhelm became almost an alibi for men who were even blinder than he yet possessed greater power. In his astonishing book about Germany’s collapse published in 1924, Charles de Gaulle enumerated “the defects common to these eminent men: the characteristic taste for immoderate undertakings; the passion to expand their personal power at any cost; the contempt for the limits marked out by human experience, common sense, and the law.” But beneath them was an all too accommodating German bourgeoisie, whom Max Weber, in a phrase that resonates across the decades, urged to throw off “the cowardly will to impotence.”

Our nation is not like imperial Germany, and great as our dangers are, they can’t be compared to the horrors of that earlier time. But there may be a distant lesson from a country whose rulers in war, quarreling among themselves, inflicted unimaginable harm to their people and to the world with their mendacity, secrecy, and paranoia. The consequences of their leadership—bolstered as it had been by claims of divine guidance, shrouded in chauvinism, and fortified by the cunning manipulation of pervasive fear—became fully manifest only later, as the people of an aggrieved nation turned against each other, almost reveling in their deep political and moral divisions and hatreds. It took a worse catastrophe, a world-historical scourge, to teach a lesson to these affected people. By distant analogy, we too might learn a lesson about the dangers and follies of imperial hubris.