Siren, possibly commissioned by the Colonna family, Rome, c. 1571–90. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers and Edith Perry Chapman Funds, 2000.

Evil have I done…and sorrow shall I know till my redemption comes.

—H. Rider Haggard, She

Perhaps the creepiest scene in Jordan Peele’s 2017 breakout horror-satire Get Out shows millennial hipster Rose Armitage (Allison Williams), all ponytailed hair and luminous white skin, sipping milk and nibbling Fruit Loops as she combs the internet for a new black boyfriend. If all goes well, her next beau will take his place among the trophy photos of black men neatly hung behind her bed, each one lured into a hellish scheme in which Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner turns out to be (spoiler!) Guess Who’s Getting His Brains Carved Out.

Spawned by a family of racist maniacs posing as Obama-worshipping northeastern liberals, Rose is the scariest of them all. The flower of white womanhood is a straight-up psychopath. Audiences didn’t see that one coming.

Apprehension about the white woman born to relative affluence has lately seen a spike. What distance spans her outer and inner worlds? What is the nature of her liberties and limitations? Her rites and rituals? Is there something unheimlich lurking behind her sunny smiles and bouncy ponytails?

When 2016 election postmortems found that 53 percent of white female voters and 45 percent of white female college grads had ticked the box for the pussy-grabbing, race-baiting Donald Trump, liberal celebrities like Lena Dunham got triggered, while media sages widely suspected closet bigotry. Headlines like those concerning the Miss Teen USA from Texas caught using the n-word on social media highlighted a sense of alarm that rose to red alert in a January 2017 Marie Claire article that warned of middle-class “skin chicks” (female skinheads) in angular haircuts acting as sinister recruiters for white supremacists.

Voting for Hillary was no cover. Tweets and blog posts examined the sneaky habits of liberal coastal women pretending to be do-gooders while throwing the oppressed under the bus. Democrat-leaning pop stars like Taylor Swift were criticized for racial tone-deafness and whitesplaining, while comments on the 2017 Women’s March—touted as an act of resistance to an evil male overlord—revealed exasperation with the serene cluelessness and shallow inclusivity of Hillary supporters turned out in knitted pink hats.

As political and social unrest percolates, the white woman’s sticky, tricky role in American history gets a rethink as she is summoned to answer for her complicity in writing the ugliest chapters. It’s time, girl, the popular chorus seems to say.

Damning evidence pours in: news of Confederate statuary stripped from pedestals accompanied by reminders of the bonneted memorial-association dames who put them up complicates the ledger of justice. Was the white woman in widow’s weeds a pitiable figure or the unpardonable supporter of white supremacy? The horrific revelation that Mississippi beauty queen Carolyn Bryant, wife of shop owner Roy Bryant, lied about key details of the incident that led to her husband’s torture and murder of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in 1955 underscores a feeling that she has gotten away if not with murder, then something close to it.

Like Medusa’s snaky locks, knotty threads of race, gender, and class coil around the privileged white woman’s image—she who smilingly stabs good people in the back and lures men of all colors into ruin, all the while simmering with latent violent passions. As siren, psychopath, and masked devil, she is a fiend for the new millennium.

The white woman is the new monster in the house.

Peele’s sneaky, freaky Rose may be a fresh incarnation of devilish white femininity, but her heritage owes something, oddly enough, to a nineteenth-century angel.

In 1854 English poet Coventry Patmore unleashed the ideal of the “Angel in the House” in a paean to the domestic perfection of his wife, captured in her milk-white, beribboned glory by John Everett Millais. Patmore’s middle-class white goddess winged her way across the Atlantic, donning aristocratic trappings in the American South, where she was to be pure both sexually and racially. Southern planters, needing to compensate their wives for their inferior status and their own nighttime exploits in the slave quarters, made them an offer they couldn’t refuse: they would be praised and obsessively protected as emblems of pure femininity at the price of their natural sexual instincts and a promise to uphold a monstrous established order.

The Angel struck a deal with the devil.

The romanticized version of her role as plantation dame conjured a parasol-toting paragon of domestic virtue engaged in cooperative, and even benevolent, relations with enslaved workers—a mythology that obscured the fact that she could, and did, visit them with neglect, hostility, and physical abuse as enforcer of household discipline.

Cracks appeared in the porcelain image to betray the Angel’s strain. Out of the watchful eye of her male relatives, she became a fickle coquette, or, during the Civil War, a musket-packing mama who shamed her men with the steeliness of her martial spirit. Later, under Jim Crow, she was appointed the ready excuse for the white man’s violence, born as much of the fear of her growing independence as a voting citizen and workforce participant as the terror of black male sexuality and vengeance. Through it all, her conflicting identifications as white, female, and well-off—at least in relation to black people and the whites derided as “trash”—made her a confusing, mutating figure: by turns steel magnolia, petticoated villain, and Blanche DuBois–style victim.

Though particularly useful to the slaveholding South, this Angel/Devil was never bound to one region. The Cult of True Womanhood, an extension of the Angel in the House franchise especially popular in the northeastern United States, spread images of white feminine purity and piety in the middle and upper classes through sermons and ladies’ magazines during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an influence that tainted white feminism with sanctimony and hypocrisy. Some white suffragettes leveraged the Angel’s popularity to court racists and argue for their own suffrage at the expense of people of color. This treachery still rankles black feminists who find white women’s adulation of figures like Susan B. Anthony—certain that she would rather “cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman”—to be as insulting as the “cringeworthy” performances of the Clinton campaign, which called upon women to #WearWhiteToVote in 2017, a tribute to these same suffragettes.

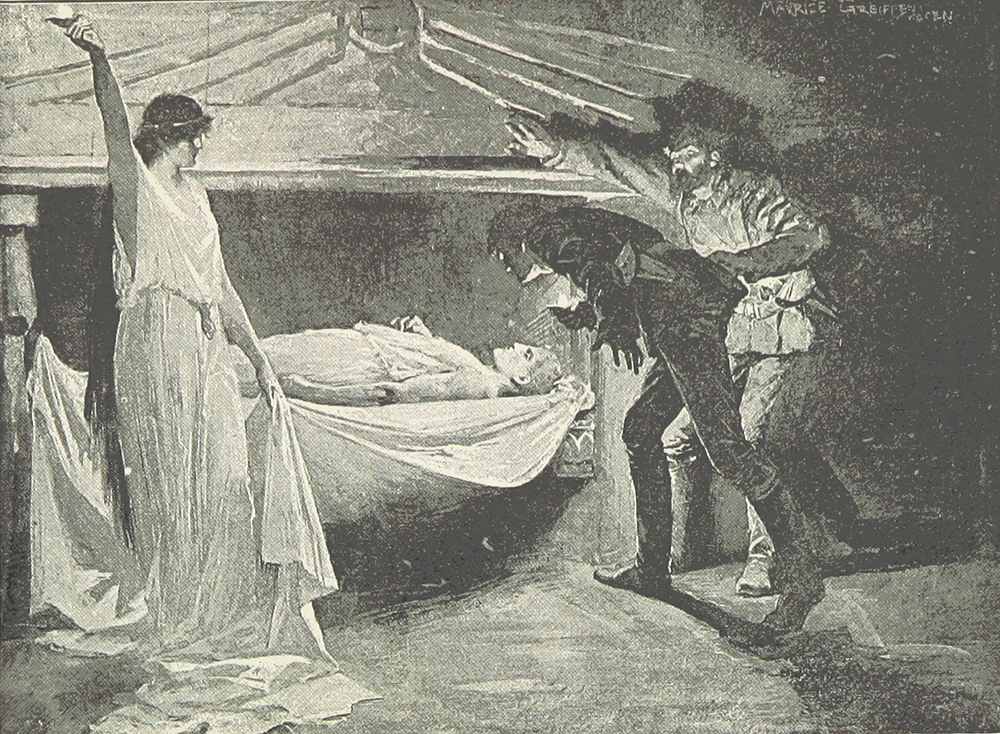

Wherever she went, an enduring question about the Angel haunted the collective psyche: just how contented was she with her bargain? Fears—as well as fantasies—that she would leap off her pedestal to cause havoc down below preoccupied writers and moviemakers who created a sinister roster of evil white sirens and matriarchs who needed to be gotten in line. Some imagined that the privileged white woman’s sexuality, having no enjoyable outlet, would be turned into a weapon against men. Others had a hunch that her resentment of the white men in power might produce a dangerous schemer or would-be tyrant.

These tensions gave life to a special form of monster, not altogether human, divided and self-estranged—willing to please only to destroy.

British adventure writer H. Rider Haggard’s 1886 adventure tale She, one of the best-selling novels of all time, crystallized these anxieties, which were amplified by the twin blows of loosening restrictions on women and imperial decline. From a vision of demonic womanhood so potent that it haunted the dreams of Sigmund Freud, Haggard called forth the ultimate white siren-bitch: Ayesha, the two-thousand-year-old queen of a lost matriarchal African civilization who is known by her subjects by the dread title She-who-must-be-obeyed.

Ayesha, a woman “white as snow,” embraces a racist theory in which original pure light-skinned peoples have degenerated into hordes like the dark-skinned cannibals she rules with murderous cruelty, occasionally subjecting them to breeding experiments. Her power resides partly in her whiteness: Holly, the bigoted British narrator, initially dismisses the notion of meeting a “swarthy and dusky queen,” but succumbs upon beholding Ayesha’s splendid pallor.

She is a beautiful fallen angel, her intellect “supernaturally sharpened” and her passion—demonstrated by her enduring love for a man dead two thousand years she believes to have been reincarnated in Holly’s adopted son Leo—frighteningly excessive. Satanically ambitious, she boasts of living “above the law” and aims to take over all the empires of the world. Ayesha’s story, in which a powerful and wicked white woman is ultimately overpowered by white men, has held perennial pop-culture fascination, from Merian C. Cooper’s 1935 film adaptation (with future congresswoman Helen Gahagan in the title role) to the 1965 Hammer production starring the iconic bombshell Ursula Andress as the sadistic queen.

The trope of the evil and powerful white woman is a Hollywood staple. For a recent example, see the 2016 TV series American Horror Story: Roanoke, which presents a menacing Kathy Bates as Thomasin White, aka “The Butcher,” wife of the governor of an ill-fated sixteenth-century English settlement in North Carolina, and a seductive Lady Gaga as Scáthach, a sexually rapacious sorceress.

Left in charge while her husband sails for supplies, Thomasin finds the colony turned against her authority but is spared death by Scáthach, an Englishwoman who called upon dark pagan gods to massacre the soldiers who nearly burned her at the stake after they accused her of bringing the plague to the ship upon which she was a stowaway. Scáthach takes possession of Thomasin’s soul in exchange for saving her life, later encouraging her to slay her would-be killers by chopping them up with a meat cleaver. This horror is the backdrop of a modern-day story in which Thomasin’s ghost threatens an interracial couple living on the massacre site while Scáthach gets her kicks luring Matt, the black husband, into steamy sex he is unable to remember.

Thomasin’s ability to butcher from beyond the grave is terrifying, but the predatory eroticism of the white siren-bitch who strips men of their agency (and their clothes) threatens not just mortal life but sanity. Scáthach flouts the laws and customs dictating marriage, religion, and the sexual activities of men who are historically ordained to do the lusting and the chasing. Like Chris in Get Out, Matt can’t resist the call of the siren, a fatal mistake. Though Roanoke producer Ryan Murphy has been applauded for his female-centered stories, some detect a whiff of misogyny in his stereotypes. Roanoke seems to imply that you can’t run a colony (or anything else) with powerful white women unleashed.

Prestige moviemakers have lately gone back to the Civil War era to weigh the privileged white woman’s guilt and take measure of her monstrosity. In Quentin Tarantino’s revisionist Western Django Unchained, Lara Lee (Laura Cayouette) is the widowed sister of slaveholder Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), the despicable owner of Candyland plantation. Her saccharine deference to her brother might be construed as the piteous necessity of a female dependent, especially given his incestuous leering, but at times she seems relish her role as the devil’s handmaiden. In one scene, she intercedes for an enslaved housemaid who is subjected to Candie’s brutality at the dinner table. But Tarantino interprets her act as more a matter of propriety than mercy, and in the end his hero Django (Jamie Foxx), a former slave turned bounty hunter, renders a fatal verdict when he gleefully guns down Lara Lee in a plantation high noon. Tarantino obliterates any moral ambiguity in a single rifle blast: she dies, along with Candie, the rest of the whites on the plantation, and one black character, a senior house slave named Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson) who is loyal to Candie. You made a deal with the devil? You’re done.

English artist and film director Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013) renders a more complex portrait of the perilous power and gender dynamics of the plantation. His story, based on the 1853 memoir of Solomon Northup, a free-born violin maker kidnapped into slavery, depicts the suffering of Northup’s close acquaintance Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o) at the hands of the brutal Louisiana slaveholder Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender) and his wife, Mary (Sarah Paulson), who is incensed at her husband’s sexual fixation on the enslaved woman.

Both Mary Epps and Patsey are traumatized by their white overlord, but Patsey is by far the more vulnerable. Northup does not mention violence on Mary’s part, but McQueen dramatizes the story of her jealousy by having Mary not only humiliate Patsey but physically attack her, at one point launching a glass decanter at her rival’s face. Mary’s uncontrollable fury topples her from the Angel pedestal while the reality of her power in the hierarchy of slavery gives her an outlet for vengeance. She can’t feign blindness to her husband’s activities, and her estranged rage, rooted in the irreconcilable demands of her position as plantation mistress to uphold her husband’s authority and her human fear of abandonment, pushes her over the precipice. Paulson stated that in order to play Mary, “I had to find a way into what happens when you feel you are losing the only thing you have, which is your standing in your own home and your respect.” Mary becomes a monster in muslin ruffles, protecting a position that is hopelessly compromised.

The theme of protection—and just who is protecting what—surfaces in The Beguiled, Sofia Coppola’s 2017 Southern Gothic remake of a 1971 Don Siegel film, based on a Thomas Cullinan novel, in which a wounded Union soldier (Clint Eastwood in Siegel’s version) finds himself in an isolated Southern girls’ academy where a few students and teachers are coping on their own in the midst of the Civil War. Both Siegel and Coppola begin with twelve-year-old Amy wandering the forest like Little Red Riding Hood when a hurt man stumbles out of the foliage. Entranced by the handsome soldier, Amy brings him home to the school, where, despite one student’s cautions about rape-inclined Yankees, he is taken in to be nursed until he can be handed over to the Confederate Army. (The student’s fear is historically well-founded: despite a long-standing myth that rape was a rarity during the Civil War, recent research reveals its prevalence among both white and black Southern women as Union troops invaded.)

Corporal John, a charming womanizer with a vicious streak, played by Colin Farrell in Coppola’s version, preys on the romantic dreams of virginal teacher Edwina (Kirsten Dunst), fornicates with a student (Elle Fanning), and provokes the lust and the wrath of headmistress Martha, portrayed with a tense combination of refined sweetness and restrained aggression by Nicole Kidman.

When John reinjures himself in a fall after struggling with an enraged Edwina, who discovers him in flagrante with the student, Martha makes a medical call that cripples him in order to save his life. Or is it to punish him? It’s not quite clear—yet Coppola’s sympathy seems to lie more with Martha than with the increasingly violent soldier. The females in her film are struggling under prim restrictions that don’t serve their present circumstances (French verb conjugation does not yield food or protection), and they yearn for something beyond the dull routine of prayers and schoolbooks. Martha, once mistress of the plantation that now houses the school, may be disturbed, but she is not inherently evil. She is caught between trying to ensure the survival of the girls in her care and to sort out her desire for a handsome—and treacherous—stranger.

Coppola made a decision that probably enhanced the possibility that audiences would not find Martha irredeemably monstrous: she dropped the character of Hallie, a black housemaid featured in Siegel’s version. The exclusion has been criticized as whitewashing, but for a white female director to tell a story in which an enslaved woman sides with white Confederate women against a Union soldier (even one who threatens to rape her) might have been worse. (In response to the backlash, Coppola expressed her desire to focus on the isolation of the white females and not “insult” the legacy of slavery by featuring a black side character.)

In Siegel’s film, Hallie is a strong character under no illusions about her relationship to Southern whites, but she recognizes that a rapist is a rapist, whatever color jacket he wears. The director makes John’s ugly misogyny clear when the soldier blames his predicament on Edwina, the “virgin bitch” whose reticence forced him to satisfy his lusts with a pupil, the act which leads to Martha’s outrage and her medical ministrations. Yet the 1971 trailer for The Beguiled emphasizes the threat of “man-deprived” females who view the soldier as the “sexual enemy,” as if it would be unthinkable for audiences to sympathize with women, white or black, who act out against a white man in their power—even one who is clearly a danger.

In 2016 McQueen announced his plan to team up with American author Gillian Flynn on a female-led heist thriller as his next project.

Flynn knows something of dangerous women. Her 2012 best-selling novel Gone Girl, adapted for the screen by David Fincher in 2014, features what Vanity Fair’s Katey Rich described as “the most disturbing female villain of all time”: a pretty young writer-cum-sociopath who fakes her own death, frames men for rape and murder, and carries it all off with brilliant panache. In an especially disquieting scene, the lovely, blond Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike) lures her outwitted husband into the shower as she soaps away the blood of a man she has offed at the moment of orgasm.

Amy’s sociopathy developed while chafing under the roles everyone insisted that she play all her life: a perfect daughter known as “Amazing Amy” in children’s books written by her parents, an eternal object of desire for an ex-boyfriend, and an impossible “Cool Girl” for her husband, who happens to be a shiftless jerk who sleeps with his student.

Amy opts for none of the above. She maintains the veneer of all those roles, at least until she disappears, but reinvents herself as angel of spousal vengeance. Here the wicked and powerful white woman doesn’t just jump off the pedestal to wreak havoc. She doesn’t just get away with it. She doesn’t just best her opponent. She owns him—forcing husband Nick to assume the role of her subservient spouse and raise a child she has conceived by stealing his semen. Readers and movie audiences were stunned.

Some have called Gone Girl a feminist manifesto; others denounce it as “misogynist agit-prop.” Amy is undoubtedly a monster, but there is logic in her desire to shake up the society that steered her to the thankless role of contemporary Angel in the House, a persona that ultimately bored her husband. Amy, painfully insecure, needy, and lost underneath it all, is unable to productively channel her energy and extraordinary intelligence into anything that feels real. “Sociopath” is the only role that seems to fit. So she plays it to the hilt.

Flynn offers an insight into what might be so upsetting about the sight of a privileged white woman—or any woman, for that matter—acting the part of a sociopath. In her essay “I Was Not a Nice Little Girl,” she reveals that as a kid her favorite summertime hobbies were feeding ants to spiders, taunting her cousins, and checking out softcore porn on cable TV. Her Kansas family was perfectly normal, she insists. Flynn did these things not because of trauma. She did them for no particular reason at all. “Men speak fondly of those strange bursts of childhood aggression, their disastrous immature sexuality,” writes Flynn, but women aren’t meant to speak of them; such girls aren’t even supposed to exist. As their sense of themselves takes shape, little girls are not allowed to say what they are and wind up estranged from themselves—a tension they carry as adults. Could this be the uncanniness behind the smile?

In reality, of course, they are human and possess the full range of human instincts: curiosity, aggression, desire, and love. But they’re still not supposed to show all of this at the same time.

In Get Out, it makes intuitive sense that Rose the Psychopath, with her fondness for milk and teddy bears, is infantilized, because the development of the feminine inner life has long been a subject of evasion and unease. After the Pill and the sexual revolution, Hollywood responded with an obsession with the Monster White Girl, the one whose maturing is a source of horror, most notably in William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), where the spectacle of a button-nosed twelve-year-old who morphs into a filthy-mouthed demon masturbating with a crucifix channeled fears of the white female’s uncontrollable and dangerous body as she reaches puberty. The white girl’s menstruation leads to madness in films like Alice, Sweet Alice (1976) and Carrie (1976) on up to Ginger Snaps (2000). Growing up is not really an option.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the story of the privileged white woman is one of evasions, reactions, and retroactive justice. She has been both overvalued and devalued. But she is also empowered in ways not available to her foremothers, equipped with tools to heal her estrangement and locate her real humanity. Can there be redemption? Exploring the white female as monster actually provides opportunities for both liberation from fantasy and a reckoning.

Peele has cheekily forced that lineal descendent of the Angel in the House, the Good Samaritan liberal white female, to expose her hypocrisy—a problem that voting for candidates who uphold a predatory plutocracy, whether named Obama or Hillary, most assuredly does not solve. Nor does following a foggy line of resistance to an orange-haired tyrant if that resistance still includes policies that keep plenty of people—men and women—from getting single-payer healthcare and other obvious things they need. The goodies offered to the privileged white woman trying to shatter glass ceilings still often require making deals with today’s devils, whether the prizes are fancy diplomas, coveted corporate jobs, political perches, marriage certificates, or stints at having-it-all helicopter motherhood. She is still tempted to squeeze herself into Oscar-worthy performances and wear masks that distort what’s underneath, turning her into an uncanny automaton, a willfully blind Pollyanna, or an Angel run amok.

Yet perhaps the time is finally ripe for such women to proclaim what is rightfully theirs (the full spectrum of their sexuality, competencies, and ambitions) as well as the parts hidden away in shame (pent-up aggression, divided loyalty, will to power, and a maddening tendency toward self-deception).

Of the Angel in the House, Virginia Woolf once wrote, “She bothered me and wasted my time and so tormented me that at last I killed her.” She may not be quite dead, but in breaking taboos with their monster-in-the-house creations, artists like Peele and Flynn may be giving her an opportunity to examine herself, move closer to authenticity, and to express herself fully, neither as angel nor devil. Just human.

And to stop making deals with devils, once and for all.

Explore Fear, the Summer 2017 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.