Dream (Rêve) (detail), by T.P. Wagner, 1894. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1922.

In encountering a work by Anna Kavan, the first thing that needs to be understood is that Anna Kavan is difficult. Kavan lived a difficult life, and she took elements of that life to write some exceedingly difficult books. She made it difficult for her to be known or understood, destroying most of her diaries and correspondence and speaking only vaguely, if at all, about most aspects of her life. She did not give interviews or commentaries (not that there was much demand). She reinvented herself and her writing multiple times. She was not unaware of this effect. “I was about to become the world’s best-kept secret, one that would never be told,” Kavan wrote in an unpublished story. “What a thrilling enigma for posterity I should be.”

Difficulty is not the most encouraging association to place on an author. When given to one who is female, it can amount almost to fastening a weight and chain to her work. But for Anna Kavan that difficulty is both verifiable and paramount. Difficulty was part and parcel for her because the worlds she sought to create were not easy ones to live in. Kavan’s fiction tested the boundaries of narrative. Mundane objectivity, rendered with cold economy, was a facade easily torn apart by her lyrical nightmares. Her language could turn a man into a monster, a home into a black hole, and encase the earth in permanent winter. Her vision compelled other convention-flouting talents—Doris Lessing, Anaïs Nin, J.G. Ballard, L.P. Hartley, Lawrence Durrell, and Jean Rhys—to praise her. By the time she died at age sixty-seven from complications related to her heroin addiction, she had become a bona fide cult figure—or, more accurately, a cult figure among cult figures.

Such status does come with certain problems. Kavan’s work is routinely susceptible to comparison traps—true of all artists, but nigh on inescapable for Kavan, whose work is often spun as an offspring of Virginia Woolf and Franz Kafka. Those influences are present, of course, but their conjuring often paints Kavan as derivative rather than foundational. And then her extraordinary life—specifically her nearly four-decade dependency on heroin—tends to consign her and the “hallucinatory” quality of her writing to the realm of drug literature.

Kavan’s influences and experiences sifted into her work in fascinating ways, but her best work defies the expectations created by these reference points. “I should have been inured to climactic changes,” she wrote in her novel Ice, “but I again felt I had moved out of ordinary life into an area of total strangeness. All this was real, it was really happening, but with a quality of the unreal; it was reality happening in quite a different way.”

Anna Kavan was born Helen Emily Woods in 1901 in Cannes to expatriate upper-class English parents. The household showed no particular warmth for children: Kavan’s early life was spent largely in her parents’ trail as they moved to London and to North America, leaving her first in the care of wet nurses and then in boarding school after boarding school. Of Kavan’s father we know almost nothing other than that he drowned in Mexico, likely a suicide, when she was in her teens. Her mother, also named Helen, is remembered largely as cold and domineering, the kind to provide financial but almost no emotional support for her daughter.

Kavan’s mother is a continual presence in her fiction as a distant but antagonistic figure. “She is nearing forty, her still young face is attractive in spite of the discontent harassing it,” Kavan wrote of the protagonist’s mother in Sleep Has His House. “My mother disliked and despised me for being a girl,” she wrote in the posthumously published story “World of Heroes.” “From her I got the idea that men were a superior breed, the free, the fortunate, the splendid, the strong.”

It was through her mother that Kavan met Donald Ferguson, whom she married at age eighteen. Kavan’s biographers have said that Ferguson was the lover of Kavan’s mother, who forced the marriage in lieu of Kavan attending university, but beyond what appears in Kavan’s fiction, this account, like many other aspects of her life, remains speculative. The couple moved to Burma, where Donald worked as a railway engineer. She bore a son, Bryan, in 1922, who was killed in 1944 while serving in World War II. The marriage was unhappy, possibly even violent; it ended when she returned to Europe.

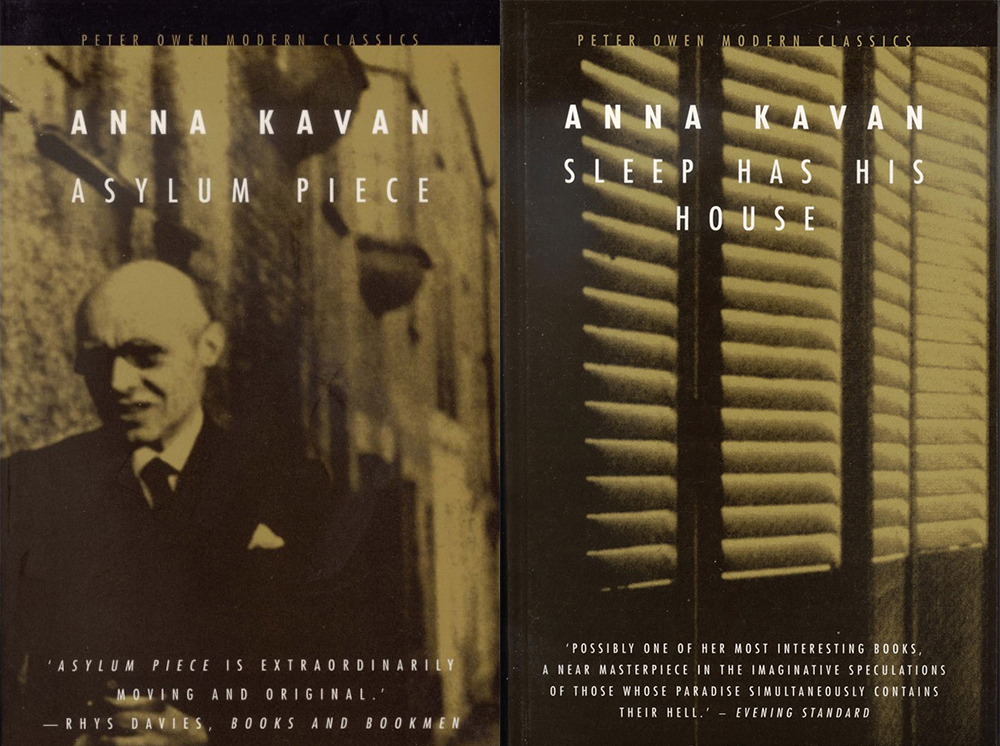

Kavan began writing while she was still married to Ferguson, and her debut novel, A Charmed Circle, was published in 1929. She published it under the name Helen Ferguson, which she used for the five novels that followed. Her work as Ferguson is often sidelined, labeled “conventional” or, conversely, “eccentric.” Anna Kavan Society chair Victoria Walker wrote that these novels “won neither effusive praise nor censure and largely did not sell.” They are bleak, tonally inert depictions of domestic life in the English home counties, wherein young women are psychologically imprisoned by cold, domineering parents and/or spouses. “A Brontë influence seems to pervade the early part of this novel,” Kavan’s friend and fellow author Rhys Davies wrote in his preface to a recent edition of her 1930 novel Let Me Alone. “Later, more than a hint of D.H. Lawrence of Women in Love pervades its language.”

Of the six Ferguson novels, three—A Charmed Circle, Let Me Alone, and A Stranger Still—have been republished. The latter two are significant because they introduce Kavan’s most notable character: Anna Kavan. They also introduce Kavan’s most potent and perennial themes, centered on the psychic ramifications of going from an unloving family to an unloving marriage. Let Me Alone focuses on the deterioration of Anna’s marriage to Matthew Kavan while living in a tropical colonial outpost: “Matthew had turned her into an automaton, destroying her individuality. It was his influence making her unreal. She felt as though she had lost herself. Her personality was absent. She was like a mechanical thing moving about with no real existence.” Later, after Kavan dropped the Ferguson name, she would return to this narrative.

In 1928 Kavan married a second time, to artist Stuart Edmonds, and became Helen Edmonds. She and her husband traveled through much of Europe, had a daughter who died in infancy, and adopted another daughter. By this point, however, she had become addicted to heroin—allegedly introduced to it by a tennis instructor—and her husband was an alcoholic. They divorced in 1938, and their adopted daughter seems to disappear completely from her life. Kavan suffered a nervous breakdown soon after, and underwent treatment in a psychiatric hospital in Switzerland. Following her release in 1938, she legally changed her name to Anna Kavan. In addition, she dyed her brunette hair blonde and lost considerable weight. She moved first to the United States, then to New Zealand, where she lived with conscientious objector and playwright Ian Hamilton, before making an arduous wartime trek through Asia and back to London. She worked as a secretary and contributor for literary critic Cyril Connolly’s Horizon and later as an interior designer—all this in addition to painting, which she took up not long after writing.

Made up of short stories based on her time at the hospital, Asylum Piece (1940) was the first book she published as Anna Kavan. Mental illness figures heavily in this and other early Anna Kavan works, including the collection I Am Lazarus (1945), which drew on her time working at a London hospital during World War II, when she was tasked with interviewing neurologically afflicted soldiers about their conditions. It includes “The Blackout,” which ran in a 1945 issue of The New Yorker:

The boy was not lying on the couch anymore but bending over with hunched shoulders, as if hiding from something, his head on his raised knees in the posture a person might take crouching under a table, and though he was crying, he was no longer thinking of the tunnel or of the dangerous secret thing which had scared him so terribly or about anything he could put into words.

The early stories written under her new name bear a traceable Kafka influence, fixated as they are on the slippery bounds of sanity, the absurdities of institutional life, and the oppressive hold nameless authorities have over those trapped within it. Her 1957 novel Eagles’ Nest, about an artist who accepts a commission from the mysterious occupant of an isolated mountain mansion, bears the strongest Kafkaesque mark. At the same time, Kavan’s style became more flexible. While her early novels were pointedly bleak kitchen-sink realism, her work as Anna Kavan took on more puzzling and ominous dimensions. Although her fiction from 1940 until her death often retraced similar themes, it never stayed in the same place. Asylum Piece and Eagles’ Nest were recognizably existentialist. The Scarcity of Love and A Bright Green Field were sojourns back to her pre-1940 style as Helen Ferguson. But in the course of her career, especially in the later part of it, she was able to publish novels in which her own vision dominates over any obvious influence—novels in which the “Kavanesque” comes into focus.

Sleep Has His House was first published in 1947. Described at times as a novel, a memoir, or a collection of poetry, it is one of Kavan’s most experimental works, and one of her most divisive. In her brief foreword, Kavan explained that the novel “describes in the nighttime language certain stages of development in one individual human being…language we have all spoken in childhood and in our dreams.” A critic in the Saturday Review praised her for having “thrust farther into the wild brilliance and darkness of the world beyond reality than has any writer of her time”; Diana Trilling bluntly countered that “nothing makes it worth reading,” panning it in The Nation for encouraging the view “that madness is a normal, even a better than normal, way of life.”

The novel is centered on B, a young girl who lives with her mother, A. Its structure alternates between daylight and nighttime passages. The daylight passages, set off by italics, are brief and relatively restrained:

I found out that these [people] were not what they appeared; they were different from myself although they spoke a similar language. They were traitors who betrayed their dark and magical origin for the cheap citizenship of the day. When I discovered this, my confidence vanished, I felt afraid and ashamed. It was a terrible disappointment, a dreadful humiliation.

By contrast the nighttime sections are expressionistic third-person expansions of the daytime passages, processions of narrative discordance and poetic potency associated with dream logic:

At the palace a state ball is in full swing. The great building, with every window aflame, rides the night like an enormous ship, isolated as it is from the glaring streets in a dim sea of encircling gardens where only the fairy-lights show a pale luminous phosphorescence among the trees and the sleeping roses.

Sleep Has His House is less “better living through insanity” and more surrealist coming-of-age novel. It ably depicts the Manichaean melodrama of adolescence, though the hallucinatory language forms something of a whirlpool. In subsequent decades Kavan became more adventurous with form in order to depict worlds where dream and reality were not so easily partitioned.

During the 1960s Kavan grew increasingly withdrawn. Her struggle to treat her drug addiction coincided with a decline in health brought by years of drug use. In 1964 her friend, psychiatrist, collaborator, and drug supplier Dr. Karl Bluth died. Their decades-long platonic friendship had been Kavan’s most lasting relationship, and his death devastated her. The UK had criminalized the prescribing of narcotics, and Kavan was said to have begun hoarding heroin. Her paintings took on a darker cast both in color palette and subject matter, depicting acts of violence and execution. Yet the final four years of her life also saw the publication of her two most memorable novels.

Who Are You? came out in 1963, after a five-year publication hiatus. Its plot is a return to the second half of Let Me Alone. The central character, known only as “the girl,” lives with her husband “Mr. Dog Head” in a house “touched by the galloping decay of the tropics…infested by rats and termites.” Shorter than Kavan’s previous books, it is written in a style that combines her earlier sparse realism with her later poetics, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere marked by oppressive heat, invasive natural surroundings, and violence that is at once normalized and unpredictable. Dog Head’s hostility to man and animal alike is boundless, and he is never less than miserable.

The man is so full of rage that he lumps everything into one colossal grievance: the depressing room, the diabolical major, the badly functioning contraption of metal fins on the ceiling, the perfidious wife who’s dragging him down from his sick bed where he ought to be lying—where she ought to be cherishing him, waiting on him…

There’s nothing left in him now but the sort of blind fury and grievance a bull might feel, pricked by all those maddening banderillas it can’t see, stuck in its flesh, from which blood is streaming. Only it’s darkness, black blood, streaming into the room, flooding everywhere, so that he’s drowning in it.

The girl finds occasional respite from Suède Boots, another expat, who is defined almost entirely by the fact that he is kind to her: “In a sudden flash, she knows that here is someone she really can talk to—it’s like being released from solitary confinement at last!” Yet the girl, despite the reader being privy to her thoughts, is perhaps even more mysterious. With any semblance of agency taken away from her, she is a slave to her circumstances and to her environment. The characters in Who Are You? move in a world where the individual psyche is emaciated, in the case of the girl, inflamed, in the case of Mr. Dog Head, or romanticized, in the case of Suède Boots. Every time the girl hears the “brain-fever birds” chirp the titular question, there are no good answers.

The novel is also more structurally disorienting than Sleep. Its midpoint, chapters 12–15, climaxes with the rape of the girl by her husband and her frantic escape into the monsoon-drenched jungle, “a black, boiling vortex, a ripping, rushing, thundering bedlam.” The climax is repeated in the two final chapters with the same outcome but a slightly different tone: the girl escapes to places unknown, but more in determination than in fear.

To Suède Boots, the girl reminds him “of the younger sister he’s fond of, who has the same vague, dreamy, helpless look which appeals to the masculine chivalry inculcated during his school days, which he hasn’t grown out of yet.” Such protectiveness seems innocent in Who Are You? but returns with a very different angle in Kavan’s next novel, the final one to be published in her lifetime.

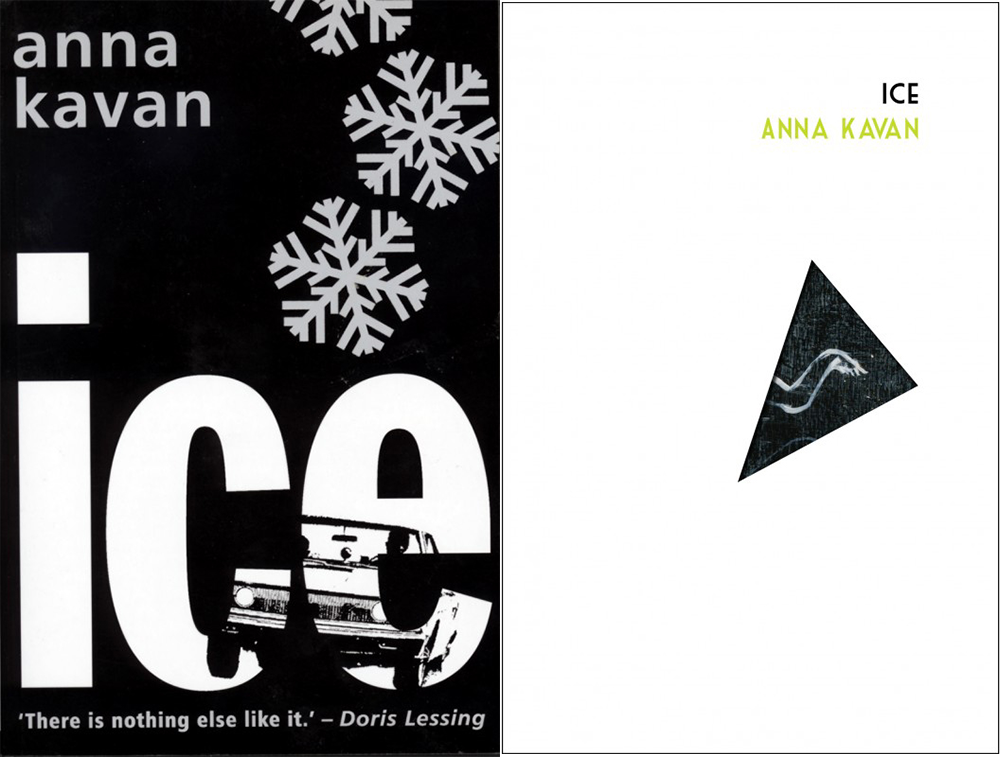

Ice is an anomaly even within Kavan’s anomalous career. Not only is it one of the few works free of autobiographical tethers, it is considered a genre piece, her attempt at science fiction. The novel takes place in an unspecified time when the earth is reeling from the effects of a global freeze. The prospect of mass extinction causes panic as nuclear-armed nations begin to annihilate each other and themselves. The narrator, a nameless man, treks through what land remains in search of a woman, another girl, he is determined to protect.

It is essential for me to find her without delay. The situation was alarming, the atmosphere tense, the emergency imminent. There was talk of a secret act of aggression by some foreign power, but no one knew what had actually happened. The government would not disclose the facts. I was informed privately of a steep rise in radioactive pollution, pointing to the explosion of a nuclear device, but of an unknown type, the consequences of which could not be accurately predicted.

The world of Ice never relents from this maelstrom. The man’s single-minded determination gets him through variations on the same chaos: lands succumbing to the control of warlords, their people driven to riot with diminishing resources, every mark of civilization in his wake “changed into anonymous white cliffs.” Yet his obsessive connection to the girl is tenuous at best, and her waifish, albino description belies more a doll than a human: “Her prominent bones seemed brittle, the protruding wrists bones at a peculiar fascination to me. Her hair was astonishing, silver-white, an albino’s sparkling like moonlight, like moonlit venetian glass. I treated her like a glass girl; at times she hardly seemed real.” Still, he claims his “aim had been to shield her from the callousness of the world, which her timidity and fragility seemed to invite.”

“Reality has always been something of an unknown quantity to me,” the man admits in the first chapter. Ice is an epic of unreliability, where the narrator’s psychic chaos occasionally impinges on the ongoing natural and social chaos. Flashbacks and visions drift in and out of the narrative. The only other constant character is the warden, a brute tyrant who has imprisoned the girl. Drawn as an antagonist on the outset, he shares as obsessive a sense of ownership over her as the narrator does. “His face wore a look of extreme arrogance which always repelled me,” the narrator says. “Yet I suddenly felt an indescribably affinity with him, a sort of blood-contact, generating confusion, so that I began to wonder if there were two of us.”

The single-mindedness of the man’s quest seems rather small compared to the world in which Kavan has placed it. As with the oppressive tropics of Who Are You?, the encroaching winter of Ice is pitiless as it tightens its grip on all life.

I looked at the natural world, and it seemed to share my feelings, by trying in vain to escape its approaching doom. The waves of the sea sped in disorderly flight towards the horizon; the sea birds, the dolphins, and flying fish, hurtled frenziedly through the air; the islands trembled and grew transparent, endeavoring to detach themselves. To rise as vapor and vanish in space. But no escape was possible.

In his foreword to the Penguin Classics reissue of Ice, Jonathan Lethem describes it as “a book like the moon is a moon. There is only one.” The assessment seems just as applicable to Kavan’s entire body of work. Hers is a free-floating mass of no determined orbit, with an irresistible gravitational pull, but a surface that is cold and arid, and with vegetation that is either poisonous or mind-altering. But looked another way, her work is a portal.

Understanding Anna Kavan has always relied on connecting her to a literary past. Yet fifty years after the publication of Ice and forty-nine years after her death, Anaïs Nin’s descriptor of her as a novelist “of the future” comes more clearly into view—but of future art rather than of future disaster. The psychosexual inner space of J.G. Ballard, the gothic apocalypse of Cormac McCarthy, the nocturnal fairy tales of Thomas Ligotti, the transgressive drama of Sarah Kane, and the sonic dystopias of Joy Division, to name a few, seem to belong to Kavan’s world. Her vision is better primed for acceptance now because, like the ice in Ice, it is everywhere and it is irreversible.

I did not regret that other world I longed for and lost. My world was now ending in snow and ice, there was nothing else left. Human life was over, the astronauts buried underground by tons of ice, the scientists wiped out by their own disaster. I felt exhilarated because we two were still alive, racing through the blizzard together.