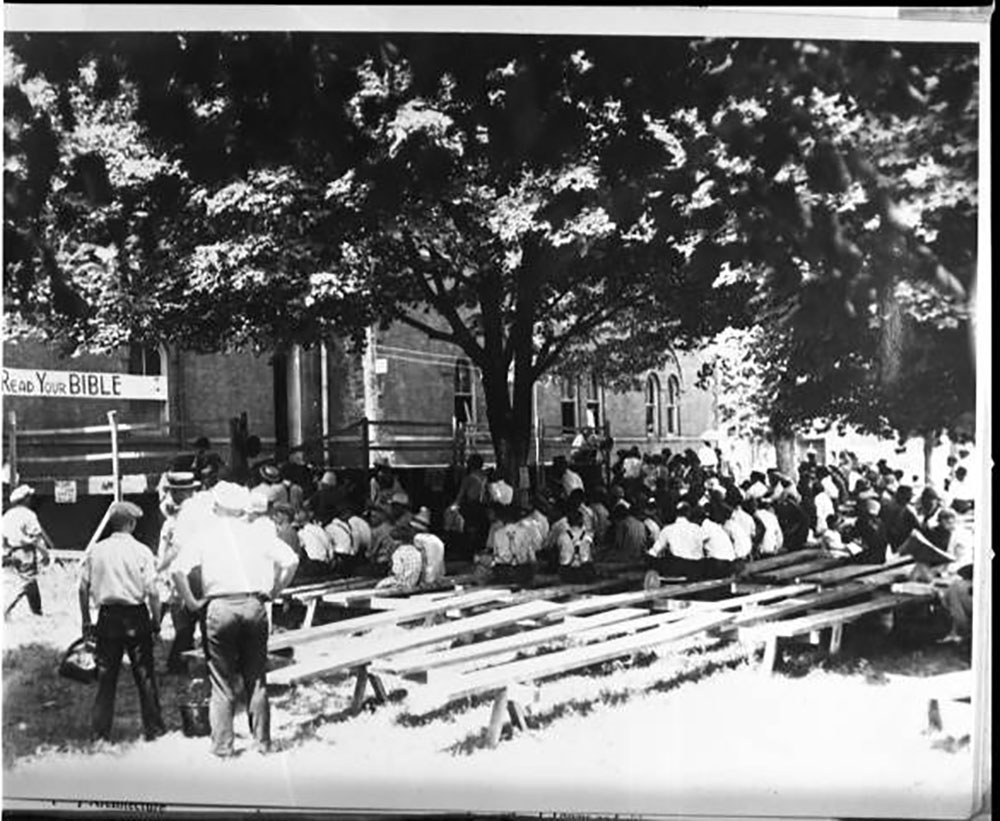

Sunday morning. Dayton, Tennessee, 1936. Photograph by Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Adapted from the preface to Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial That Riveted a Nation, from Random House Books, August 2024.

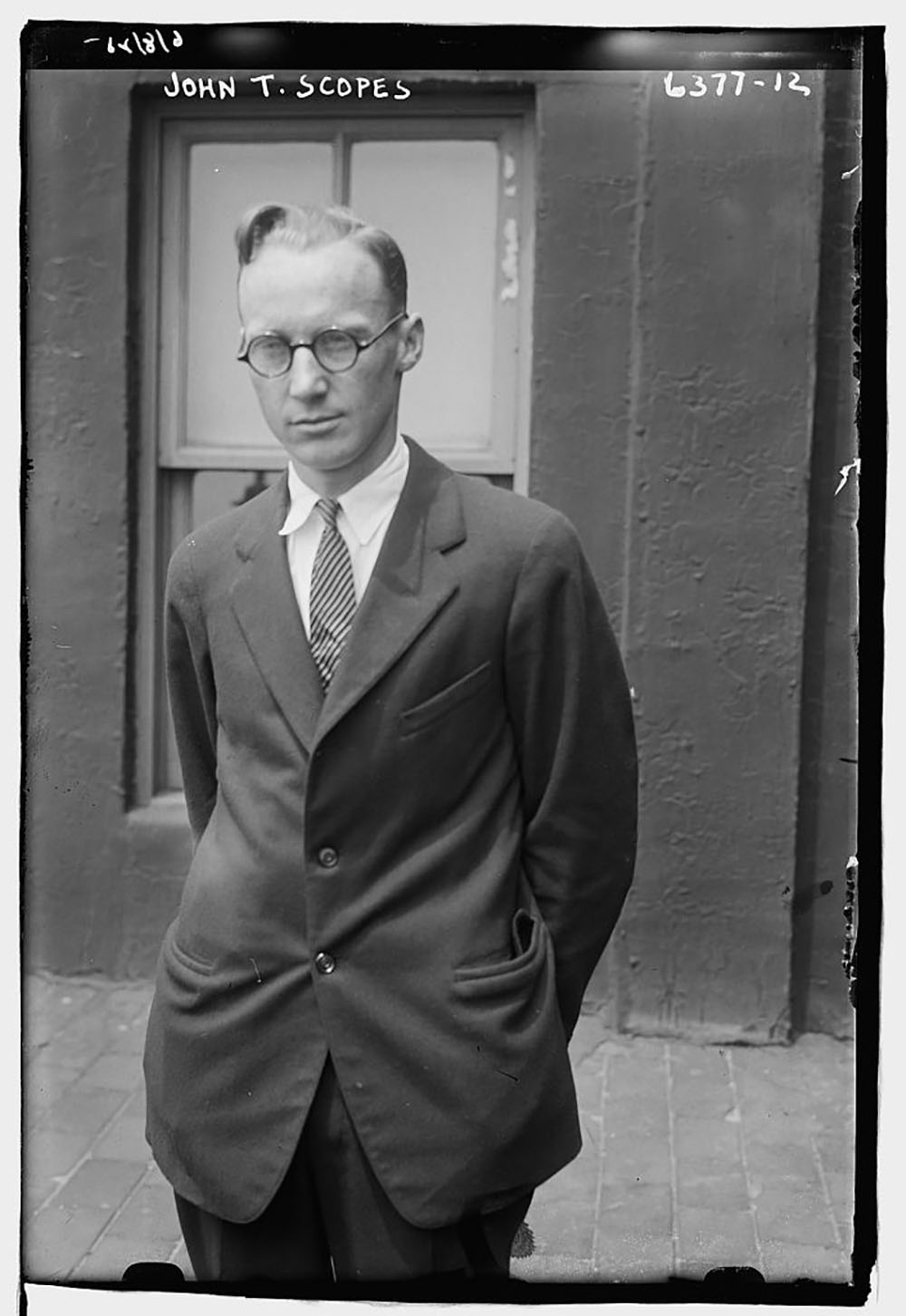

Dayton, Tennessee, was a sleepy little town at the foot of the Cumberland Mountains, with Chattanooga to the south and Knoxville to the north. Giant maple trees shaded the two principal streets, Main and Market, and along Market, farmers could still tie up their teams at the hitching rail. There were flower boxes in the windows of the homes and pretty gardens in their backyards. If the place was known for anything, it was for the strawberries that left by railroad car each spring to be distributed nationwide. That’s all, until the blisteringly hot summer of 1925, when as many as two hundred journalists descended on a town they’d never heard of. They had come to Dayton to cover what otherwise might have been a forgettable local matter—something about evolution and a young high school teacher named John Thomas Scopes.

That it turned out to be the trial of the century was, at least in retrospect, entirely predictable. America was a secular country founded on the freedom to worship, or, for that matter, the freedom not to worship. The first amendment to the Constitution asserts that Congress shall make no law establishing religion or prohibiting its free exercise; it drew a hard line, in other words, between church and state. As Thomas Jefferson put it in his Notes on the State of Virginia, “it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.”

But for many Americans, religion—specifically Protestantism—was the only safeguard against moral bankruptcy. Religion should not be separated from government; on the contrary, it should sit at its very center. To them, America was a Christian nation with a sacred mission, conceived for and by devout men who believed they were endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights. Any legislation separating church and state might well be construed as antireligious, iniquitous, even unpatriotic.

One nation, under God. One God, one nation: In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower maintained that including the words “one nation, under God” in the pledge of allegiance would strengthen, he said, “those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country’s most powerful resource.” Without our swearing allegiance to religion, the Reverend George M. Docherty had suggested to Eisenhower, “little Muscovites,” all of them godless communists, could easily be reciting the same loyalty oath.

It was not news that religion and government, religious fundamentalists and religious liberals, or even older and younger generations, would vie with one another. But in 1925, their antagonism possessed a force and a focus that surprised even the journalists who rented rooms in the small Tennessee town hoping for a scoop. After all, two gladiators, the ubiquitous politician William Jennings Bryan and the criminal lawyer Clarence Darrow, each of them national celebrities for decades, were going into battle over God and science and the classroom and, not incidentally, over what it meant to be an American.

A few months before the trial began, the Tennessee legislature had passed a law, known as the Butler Act, that forbade the teaching of “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” The fledgling American Civil Liberties Union, an organization that promised to protect the constitutional rights of citizens, claimed that the Butler Act violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious liberty. It flouted the First Amendment’s prohibition against establishing a state religion. And the Butler Act denied the right of professionals—educators—to decide for themselves, as professionals, what they should be teaching.

When the ACLU offered to defend anyone willing to test the Tennessee law by breaking it, John Scopes stepped up. Ordinarily shy, this unpretentious 24-year-old admitted that not only had he taught evolution, but you couldn’t teach biology without it. In any case, the textbook that he’d used in his biology class, a textbook the state of Tennessee had authorized, mentioned evolution in just a few pages. It said nothing about divine creation or the Bible. It had merely said that evolution was change. That was it.

Young Scopes was immediately indicted for violating the Butler Act; the trial date was set for the summer of 1925. Then the commotion began. Soon, it seemed every automobile in the country, every itinerant preacher, and every snake-oil salesman was headed for Dayton, Tennessee.

“This trial was bound to take place somewhere,” a Dayton resident philosophically observed. “It’s an issue that is coming up everywhere in the United States.” As he suspected, the issue had nothing to do with whether John Scopes had broken the law.

No one disputed that, not even Scopes himself. The issue wasn’t about the theory of evolution per se. Very few people reading or writing about the Scopes trial, or even those directly involved in it, understood how evolution occurred or even how to define it. Something greater was at stake than whether a young schoolteacher had taught from an authorized textbook that mentioned evolution.

To the celebrated criminal lawyer and self-described agnostic Clarence Darrow, who volunteered to defend Scopes, the Tennessee law raised issues that went to the heart of democracy. It asked who controlled how Americans could be educated, and where and with what means, and what limits on freedom could or should be placed on the freedom to learn, to teach, to think, or to worship. None, he said. Agreeing with him were the other members of the defense team: the Irish Catholic Dudley Field Malone and Arthur Garfield Hays, a secular Jew, who were both from New York; they were joined by the local Tennessee lawyer John Randolph Neal, the son of a colonel in the Confederate Army.

But to William Jennings Bryan, a figure as recognizable and irrepressible as Darrow, the issue was faith. The issue was God. A three-time presidential nominee and crusading leader of the Democratic Party, Bryan arrived in Dayton intending to save men and women—and children, most especially—from the warped ideas that would turn them into atheists. Although he knew little about science and even less about evolution, Bryan intuited with amazing accuracy the frustration and anger and anxiety of the people he represented and claimed to speak for, particularly the religious fundamentalists. Confident of his mission and sure of himself, he trusted he could pluck out from the public schools, and even the public colleges, the science that so offended and threatened them. This science had a name: Evolution.

By 1925 evolution had become a lightning rod, and the Scopes trial channeled the turbulence of the preceding decades, years of hunger and panic, of bombings and lynchings and riots and then a world war, the so-called Great War. There had been labor stoppages, assassinations, deportations, and great economic disparity.

The farmers of the Midwest and South, in debt, could barely make ends meet. They had even formed a political party to demand such reforms as the public ownership of railroads, which had been gouging small shippers and growers. Immigrants had been pouring into cities, crowding into tenements and working in sweatshops, until Congress in 1924 passed legislation slamming the door shut on many of them. In the South, Black men were routinely turned away at the polls, and when Black men and women moved northward, creating vibrant communities in formerly white neighborhoods, they were often chased out of their homes, their businesses and newspapers burned to the ground. The Ku Klux Klan had revived itself, in fully hooded regalia, to terrorize Blacks and Jews and Catholics, while Klan members sat in state legislatures, in governors’ mansions, and in Congress. Women were still not allowed to vote. In 1917, when they peacefully picketed the White House, they were quickly arrested. That same year, America sent its men to Europe to fight and die in a world war known for brutal, senseless slaughter on a scale never before imagined.

What’s more, discoveries in archaeology, philology, and anthropology suggested that the Bible had been written not in the hand of God but by a number of authors in a number of languages over a span of maybe a thousand years. Physicists seemed to be saying everything was relative and in flux. The old order was collapsing. The compass no longer pointed toward heaven.

Charles Darwin and the theory of evolution were not, in themselves, news either. More than six decades had passed since his On the Origin of Species first appeared in 1859, and five decades since his The Descent of Man, which was published in 1871. Darwin proposed that all living things were linked and that, over long periods of time, they evolved from far-earlier organisms in a slowly changing drama. Random biological mutations in a species would cause new characteristics to develop, and some of these characteristics could offer an advantage for that species’ survival. Take the giraffe: its ancestors resembled deer, but when food became scarce, as in times of drought, those with longer necks, even just an inch or two longer, could eat the foliage others couldn’t reach. Darwin called this process “natural selection.” Through natural selection, Darwin said, characteristics that increase the chances of survival will reproduce themselves and, over time, a new species may “evolve” while the previous one dies out.

As the biology textbook that John Scopes taught from had pointed out, evolution meant change.

Yet for many, the idea of evolution and of natural selection was hard to swallow. If humans evolved from earlier forms—if we were descended from monkeys, as Darwin was interpreted to say, which he did not—what about Adam and Eve? Didn’t God create them in His own image? And if a random mutation allowed some species to survive and others to become extinct, then accident, not design, ruled the biological universe. Where was God, then?

Or, if God existed and allowed only some select species to survive, was God immoral? Natural selection seemed to imply nothing more than struggle, conflict, and a rage for dominance.

The great Darwin popularizer, the English polymath Herbert Spencer, made some of this go down easier. In 1864, he coined the term survival of the fittest and applied Darwin to society at large. “This survival of the fittest,” Spencer wrote, “is that which Mr. Darwin has called ‘natural selection,’ or the preservation of favored races in the struggle for life.” To Spencer, natural selection was not a random process at all but rather a way to ensure that only the best or the fittest people and races would (and should) survive. Only winners in the competitive struggle for existence deserve to be winners. Nothing was random after all.

This process of allowing some species to survive and others to die actually demonstrated God’s purposeful guidance. “God intended the great to be great and the little to be little,” the liberal American preacher Henry Ward Beecher agreed with Spencer. Sidestepping the implications of a universe ruled by chance, Americans might then transform Darwin into a prophet of progress and upward mobility.

In fact, to some, that meant government shouldn’t meddle with this “natural” process by introducing, say, social programs that protected or educated the worker, the poor, or the illiterate. A perfect rationalization for laissez-faire capitalism, “social Darwinism,” as it came to be known, was embraced in the latter part of the nineteenth century by the captains of industry. They assumed it was logical—even scientific—that they, the fittest, should enjoy wealth and privilege. “When men are ignorant and poor and weak, they can’t help being oppressed,” Beecher announced. “That is so by a great natural law.”

Of course, not everyone accepted social Darwinism, which was not Darwinism or, for that matter, particularly scientific. Many, like William Jennings Bryan, confused social Darwinism with the theory of evolution. Bryan argued that evolution offered nothing more than a soulless world where only the most brutal survive. Over and over, he adamantly claimed that “evolution robs the individual of a sense of responsibility to God and paralyzes the doctrine of brotherly love.” And, if left unchallenged, the theory of evolution would deprive men and women of peace and comfort—and moral accountability—in the here and now, and it would take away the promise of happiness in the hereafter.

Evolution thus was said to endanger children, education, ethics, and, of course, religion itself. It removed God from the order of things. “Evolution is atheism,” cried evangelicals like Billy Sunday, who drew huge paying crowds.

“The evolutionists bring their doctrine before the public in a jeweled case and praise it as if it were a sacred thing,” William Jennings Bryan declared just before the Scopes trial began. “They do not exhibit, as Darwin did, its bloody purpose; they do not boast that barbarism is its only true expression.”

The old order was indeed changing, and to many Americans, change was defined as capricious, unpredictable, and, if not stopped, wholly sinister. For the Great War, too, as F. Scott Fitzgerald lamented, had left “all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.” Only drift, anarchy, and despair remained.

Campaigning for the presidency in 1920, Warren G. Harding had promised “a return to normalcy,” implicitly admitting that no one felt anything had been normal in a long time. Even that disillusioned generation of the 1920s—the people whom Gertrude Stein called “lost”—were not lost at all. They were experiencing a crisis of faith that had been ongoing for decades, and that was erupting, full force, in Dayton. “When science strikes at that upon which man’s eternal hope is founded,” one of the lawyers prosecuting Scopes poignantly declared, “then I say the foundation of man’s civilization is about to crumble.”

Argued on both sides by those who genuinely sought to make life more tolerable, more meaningful and just, the Scopes trial was cathartic, as trials generally are. It aired the uneasiness about what science seemed to portend, the pitilessness and hopelessness of it all. It aired the uneasiness about the coming role, if any, of religion in public life. It aired the uneasiness over the role of the state, if any, in dictating a civic religion that could supplant science or scholarship. In principle, then, the Tennessee law could also prevent public schools from learning about the Sumerians or the early history of Egypt, civilizations that existed before the creation of the world, as dated by the Bible. Geology would be out; botany and zoology and astronomy would be out.

There was something else, too, something less tangible. Those who flocked to Dayton and read about Dayton and made fun of Dayton were coming face-to-face with essential questions about life and death, questions that no one could completely answer—not the evangelist and not the agnostic, not the scientist, and certainly not those skeptics called modernists. “At bottom, down in their hearts, they are equally at a loss,” a reporter covering the trial suspected.

The Scopes trial was the trial of the century in a century of infamous trials: The prosecution of Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian American anarchists accused of robbery and murder in Massachusetts; the prosecution of the Scottsboro boys, nine Black teenagers who allegedly raped two white girls in Alabama; the case against Bruno Hauptmann, said to have kidnapped and murdered the baby of famed aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh; the trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, accused of handing over atomic secrets to the Soviets; and the televised trial of Black football hero O.J. Simpson, accused of killing his wife, Nicole, and her friend Ron Goldman in cold blood: trials of the century.

But here, in the small town of Dayton, in the summer of 1925, there was no murder, no robbery, no rape, kidnapping or spies. This was a different kind of trial.

Banners were hung all over town. One instructed, “Read Your Bible,” while another asked, “Where Will You Spend Eternity?” and yet another reminded folks that “You Need God in Your Business.” The local jewelry stores featured monkey watch fobs, and several shops sold toy monkeys. The meat market handled all kinds of meat, except monkey, a sign in the window declared. The local drugstore offered a drink called “monkey fizz,” and the proprietor of a dry goods store, whose name happened to be Darwin, suspended a scarlet banner on his storefront to advertise that “Darwin is right inside.”

It did seem like a circus. There were lemonade and hot dog stands set up around the courthouse, and evangelical preachers sermonized day and night on the courthouse lawn. Men in black felt hats sang spirituals on street corners, and Thomas Theodore Martin of Mississippi, field secretary of the newly founded Anti-Evolution League of America, rented a storefront to flog his own book, Hell and the High Schools. The Anti-Evolution League had nailed up several posters depicting a party of apes: “Shall We Be Taxed to Damn Our Children?” it wanted to know. Two chimpanzees had been brought to town; their trainers offered them as exhibits for the defense, and when Scopes’ lawyers politely turned them down, the trainers displayed the chimps in an empty store. At the railroad junction, the brakemen on passing trains would holler, “All out for Monkeyville.”

Henry Mencken, the acerbic journalist from the Baltimore Sun, came up with the term “monkey trial,” and it stuck.

No wonder men and women regarded the Scopes trial as a misbegotten and bizarre farce played out in a country that lacked the saving graces of culture and sophistication. The Scopes trial had to be nothing more than a promotional stunt engineered by small-town opportunists and, in the end, not much different from flagpole sitting. The entire affair was monstrous nonsense, George Bernard Shaw lashed out; Tennessee was an outpost for “morons and moral cowards.” The German press called the whole thing an American circus, but their local dailies reported on it. Newspapers in Switzerland, Italy, Russia, and Japan covered the trial, and in China, sixteen provincial papers carried the latest bulletins from Dayton. “Faith cannot be protected by law nor propagated by force,” the London Sunday Times editorialized with disdain.

“This is twentieth-century America?” wondered a dazed correspondent, and the London Daily News marveled that a one-horse town like Dayton could produce such weirdness. “I would have given anything if I had only invented the Dayton affair off my own bat,” the English writer Rudyard Kipling remarked. “It was inconceivable.” Ernest Hemingway slid a send-up of the Scopes trial into The Sun Also Rises, and after the trial, Sinclair Lewis began work on his satirical novel Elmer Gantry about a phony evangelical preacher.

It was easy to shrug off the trial as a bunch of benighted white Southerners, ignorant about science and narrow-minded about religion, fighting to fend off one and to safeguard the other. It was easy to see Dayton as an intellectual wilderness, Tennessee as an offense against civilization, and America the land of Puritan bigotry. Eastern newspapers reported that the people of Dayton resented being called peasants, hillbillies, and yokels. That didn’t stop anyone, and especially not Henry Mencken, whose witty, caustic, and frequently unfair point of view about the trial dominated much of the coverage. Drubbing Southerners as rustic theologians and dunderheads who lived in the “Bible Belt,” a term he also invented, Mencken shrewdly pointed out that Dayton hadn’t cornered the intolerance market.

“It was not in rural Tennessee but in the great cultural centers which now laugh at Tennessee that punishments came most swiftly, and were most barbarous,” Mencken wrote. New York City, not Dayton, had fired teachers for protesting the recent Great War.

The far more traditionalist or conservative writers who hoped to keep Darwin out of schools were no less objective, often characterizing evolutionists and, in particular, the lawyers defending Scopes as invading vultures come to feast on the people, customs, and religion of the South. In this, the American Civil Liberties Union was for them the chief offender, with its “horde of pacifists, pro-Germans, German agents, defeatist radicals, Reds, Communists, IWWs, Socialists, and Bolshevists.” The Scopes lawyers, the ACLU, and any fellow travelers—even scientists—intended, it was said, to destroy such civic institutions as the American Legion and the Ku Klux Klan.

The lines were drawn.

But when an out-of-town reporter asked a local man, Daniel Costello, what the people of Dayton really expected from the trial (“Rental for rooms? Advertising for coal mines or crops?”), Costello replied, “They are going to have some of the greatest scientists and the greatest speakers of the world there for the trial,” he said. “They are going to get a college education for nothing.” The citizens of Dayton, the reporter concluded, were willing to face the world’s ridicule in order to learn.

Their teachers were to be the two illustrious men headlining the case. Large personalities, comfortable on a public stage and consummate performers, Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan were famous, they were infamous, and they had been sparring for years.

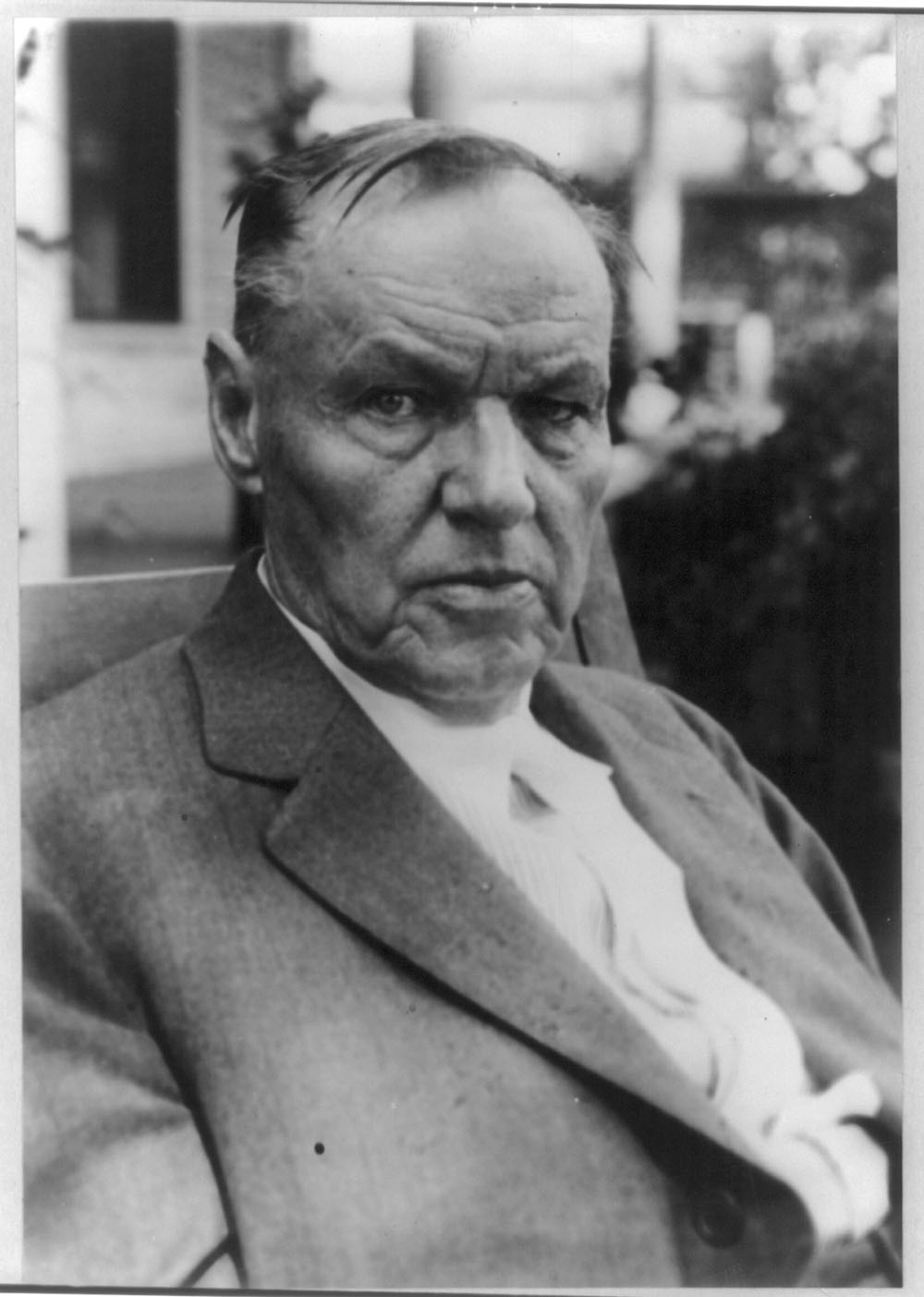

William Jennings Bryan was the de facto voice of religious fundamentalism and a leader of the Democratic Party for almost three decades. Nicknamed the Great Commoner, Bryan had for a lifetime represented the forgotten, the poor, the plain, and anyone left out of an increasingly corporate America. He believed in salvation by faith and reform by democratic action—that is, through legislation that would thwart the temptations of drink and war and godless science.

Often dismissed as a demagogue or a buffoon whose claim to fame was really failure—failure to win the White House—Bryan was mocked as the man who intended to make “Tennessee safe for Genesis.” But he was revered in many quarters of the country; people still hung on his every word; thousands went to Florida, where he was living, to hear him preach outdoors under the palms on any given Sunday. Aligning himself with conservative clergy, although he still considered himself the progressive Democrat he’d always been—on the side of the people against the plutocrats—he had taken his crusade against teaching evolution in public schools on the road, much as he had when he railed against the sale and consumption of alcohol and campaigned for Prohibition. He was a force to be reckoned with.

And no fool, he had long detected the rampant anxiety and gnawing doubt beneath the easy money and dubious morals of America in the 1920s. For this, he now blamed not just the unequal distribution of wealth but the theory of evolution and Charles Darwin. “His works are full of words indicating uncertainty,” Bryan complained, as if doubt and anxiety might be placed at Darwin’s feet. As a corrective, Bryan opted for the consolation of a theocracy—a nation of Christians that legally enforced moral behavior and could thereby revive the values that he associated with a white, rural, decent, and upstanding America. This would in turn restore, within the context of a centralized government, the pastoral life he imagined had once existed. The alternative was unthinkable.

“Mr. Bryan may protest as much as he likes that he is not a member of the Ku Klux Klan,” warned the New York World. “He is fighting with all the powers he possesses for the fundamental object of the Ku Klux Klan”—that is, for an established national church, which was un-American, lawless, and predicated on the assumption that white people were a superior race.

Bryan’s main antagonist, the star criminal lawyer Clarence Darrow, was himself both beloved and despised. With remarkable success, he’d defended socialists and anarchists, labor organizers and bomb-throwers. Just the year before the Scopes trial, he’d prevented the execution of two teenagers, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, who had killed for the thrill of it. That had been another spectacular trial, and Time magazine would name Darrow “one of the most dangerous lions of the U.S. bar.” Though no great lawyer in any academic sense, Darrow would fight desperately in the service of a lost cause, as historian Bruce Catton observed. He was charming. He mesmerized juries with his impression of humility, some of which was genuine, and with his unmatched logic and down-home wisdom. If Mark Twain had been a lawyer, people said, he would have been Clarence Darrow.

“The powerful orator hulking his way slowly, thoughtfully, extemporizing, through his long broken story,” Lincoln Steffens remembered Darrow, “hands in pocket, head down and eyes up, wondering what it is all about, to the inevitable conclusion, which he throws off with a toss of his shrugging shoulders: ‘I don’t know—We don’t know—Not enough to kill or even to judge one another.’” To Darrow, life was tragic but precious. What he said about a friend might be said of him: to his friend, Darrow said, “the earth was a great hospital of sick, wounded, and suffering.”

Still, there were those who dismissed Darrow as a crafty, publicity-hungry celebrity lawyer or atheist revolutionary without piety or scruple. To them, Darrow was a man who liked to think he was champion of the underdog and bamboozled others into believing it. Attorney for the damned, he’d stop at nothing. He must have gone to Dayton to stick pins in Bryan—and God—for the hell of it, or just to jack up his fee.

Darrow presented himself as tousled from head to toe, and no matter how expensive his suits, they crumpled with ease around his large frame. He refused to play the city slicker. Though as tall, Bryan stood erect and over the years wore what seemed to be the same black alpaca coat he had worn back in the 1890s, with the same string tie and comfortable shoes. He stooped to stylishness only when he draped a natty cape over his shoulders, though in Tennessee, walking the streets of Dayton in the oppressive July heat, he liked to appear in a white pith helmet, which protected his head from the Southern sun. Unlike Darrow, who lived much of his life in a spacious Chicago apartment lined with books, Bryan was a successful real estate entrepreneur who built himself more than one mansion set back from any crowded street.

Both of them had been born around the time Darwin’s Origin of Species was first published in the middle of the nineteenth century. They had grown up during and after the Civil War and in its shadow. Darrow’s family had been free-thinking abolitionists; Bryan’s father was a religious-minded, Southern-sympathizing Democrat who dropped to his knees three times a day to pray and advocated for what was called popular sovereignty, or the notion that citizens should decide for themselves whether, say, they wanted their state to allow or prohibit slavery—not whether it was immoral.

These two were men of the nineteenth century, coming to terms with the twentieth in the best ways they knew how. “There is a contest pending today that is not one of religious liberty, but one of economic liberty,” Darrow had declared in 1900. But Darrow was wrong if he thought the fight for religious liberty was over. It was far from over.

To Darrow, religious liberty was connected to all sorts of liberty: the right to speak, to assemble, to write, to work. Like Bryan, he considered himself a descendant of Thomas Jefferson, who believed in the rights and dignity of the mass of ordinary citizens over and above corporations and banks and even government.

But Darrow and Bryan differed in certain respects about what government should control and how it should exercise that control, if at all. They had both pushed for government ownership of such utilities as electricity, but Darrow opposed any intrusion into the conduct of private life. He loathed Prohibition. To Bryan, Prohibition was a public good. And Bryan would have the teaching of evolution outlawed in the same way as the sale and consumption of alcohol had been, likely by constitutional amendment.

Yet both Bryan and Darrow placed their faith in democracy. To Bryan, democracy meant majority rule and states’ rights. The people in each state should decide for themselves, for instance, what should be taught in state-supported schools. That was the irony of Bryan’s progressive spirit. He was the man who stood by the little people, the neglected, the poor and the weak, the man who insisted that women should be allowed to vote. Yet he wanted to make people believe what he believed, by decree if necessary.

To Darrow, there could be no democracy without reason, which is to say, without education and an educated people. For he imagined, or at least he hoped, that people might lead better, he in, more just lives if they knew more. “It was he who was the Great Commoner,” not Bryan, mourned the Black newspaper the Chicago Defender after Darrow’s death. In 1903, Darrow had declared he could envision “a universal republic, where every man is a man equal before his Maker, governor of himself, ruler of himself and the peer of all who live; where none will be excluded; where all will be included.” Though he may not have said so, Darrow did not relinquish this dream, which was not unlike Bryan’s own: the dream of a universal republic, a place where miracles had once taken place and still could. To Darrow, life was a miracle to be preserved; he acted as though it were his duty to preserve it.

Passionately disagreeing about whether the theory of evolution contradicted the biblical story of divine creation, and whether human beings are related to monkeys and whether science teachers should be allowed to teach science, Bryan and Darrow did not invent the positions they took. Rather, they came to symbolize two different and warring sides about culture, ethics, religion, and the state. And they articulated these positions brilliantly and with unfailing energy on the stump and in the courtroom.

The controversy over evolution had long been stoked both by the fundamentalist Protestants and the press, with many pundits looking disdainfully at the South and Midwest, and just as many looking with contempt at the self-appointed urban intelligentsia, loosely termed “modernists.” The Scopes trial was thus bound to be a media event that, for all its nuttiness, would encapsulate the exuberance and agitation, the snootiness and the fissures, of America in the 1920s. “Most of the newspapers treated the whole case as a farce instead of a tragedy,” Clarence Darrow later reflected.

Lining up behind Scopes were the liberal-minded men and women, whether in the church or not, who believed in the scientific method and progress. Often, they unfortunately included those self-appointed arbiters of culture, hip and disillusioned, who in their magazines and editorials sneered at what they regarded as Bible-thumpers. And the fundamentalists, as a group, were those who held fast to the Bible, to its unimpeachable wisdom, to the veracity of every word and every miracle.

The two poles did not meet. Neither the so-called modernists nor the fundamentalists could see Darrow or Bryan whole. Prejudice encountered prejudice; intolerance, intolerance. And though this compelled Darrow and Bryan, and those like them, to adopt extravagant positions, they were speaking of that longstanding debate between reason and faith, or what passed for reason and faith, which was a debate not easily resolved by extremes.

There was something tragic about the trial—Darrow was right—but something noble too. The Scopes trial reached back to the era just after the Civil War, when industrialization, immigration, and urbanization threatened institutions like the church that had once seemed—whether or not they were—coherent, comforting, and foundational. The Scopes case stretched forward to the next century, the twenty-first century, our century, when once again schools would try to outlaw certain modes of teaching or remove books from library shelves or even rewrite them in part or whole.

The Scopes case asks, then and now, where the country was headed, where it should be headed, and how to make it better and kinder in light of privation and prejudice and disillusionment and war—particularly that Great War that didn’t end all wars, as the slogan promised, but rather killed more than twenty million and severely wounded twenty million more.

“Democracy has shaken my nerves to pieces,” said the heroine of a Henry Adams novel. “I believe in democracy,” a wise friend had told her. “I have faith; not perhaps in the old dogmas, but in the new ones; faith in human nature; faith in science.”

“Free thought is the most important issue that has been raised,” the British biologist Julian Huxley remarked during the trial. “That is the real danger to a young democracy that has not got to the full pitch of its development—that it is likely to be swayed by crowd psychology and violence in expressing its opinions and forcing them on other people.”

Democracy was on trial in Dayton. As it would be again in our time: teachers being told what or how to teach; science regarded as an out-of-control, godless shibboleth; books tossed out of schools and libraries; loyalty oaths; and white supremacists promising that a revitalized white Protestant America would lead its citizens out of the slough of moral and spiritual decay to rise again, regardless of what or whose rights and freedoms might be trampled. “The truth is, and we know it: Dayton, Tennessee, is America!” the renowned Black historian and editor W.E.B. Du Bois astutely summarized. “A great, ignorant, simple-minded land, curiously compounded of brutality, bigotry, religious faith and demagoguery, and capable not simply of mistakes but of persecution, lynching, murder and idiotic blundering.” Dayton was America, and America in 1925 was a place of skyscrapers and tenements and radios, of motorcars and mustard gas, of billboards and cherished Bibles, of dispiritedness and the vexed search for something, something good, to believe in.

From Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial That Riveted a Nation. Copyright © 2024 by Brenda Wineapple. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.