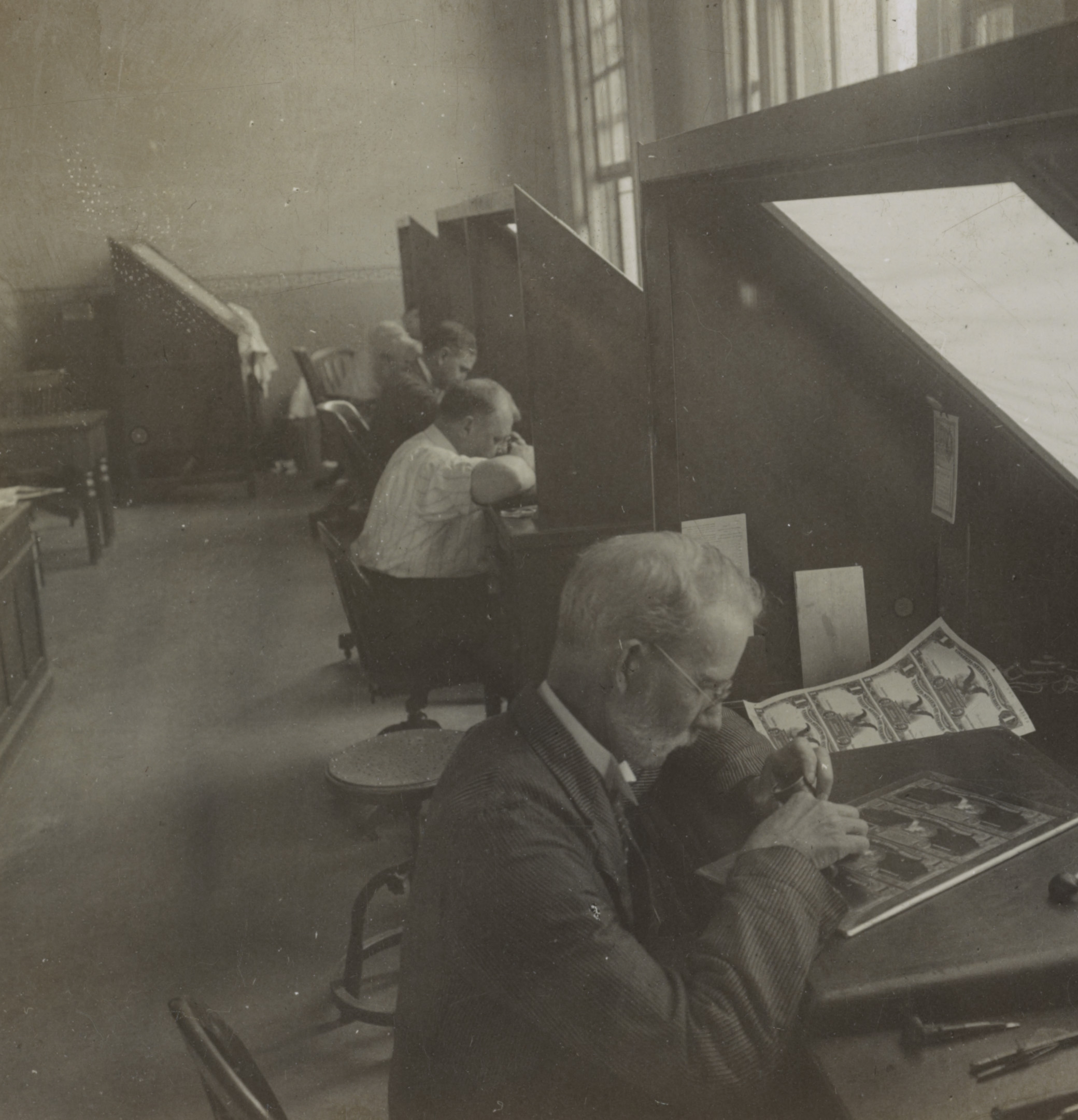

Engraving the plates for printing paper money at the Bureau of Printing and Engraving, c. 1917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In the summer of 2008, President Barack Obama claimed that “the market is the best mechanism ever invented for efficiently allocating resources to maximize production.” In expressing this view, the president was hardly alone. As the historian Richard Nelson argues, “the close of the twentieth century saw a virtual canonization of market organization as the best, indeed the only effective, way to structure an economic system.”

Yet today the wisdom of laissez-faire is being challenged with more energy than at any time since the 2008 financial crisis. Across the political spectrum, fresh demands have surfaced for the state to play a greater role in promoting economic dynamism, whether through protectionism and industrial policy or through redistributive taxes and expansive social programs—or all of the above. These demands have percolated as wealth inequality soars, growth in the “real” economy seems to have stalled, and the dynamism of capitalism itself has been called into question, especially given the emergence of “hybrid” regimes, or states that blend capitalist and socialist tendencies.

Debates about the relative merits of socialism and capitalism have raged since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. However, one chapter of sustained academic quarrelling between political economists of various political persuasions in the early twentieth century has changed the nature of these arguments forever.

What began in the early 1920s as an apparently disinterested technical dispute over the logic of economic computation and rationality had spiraled into a bitter philosophical standoff about the nature of liberty and equality. It would deeply inform the trajectory of global economic policymaking in the post-World War II period and the tenor of social, political, and economic thought throughout the latter half of the twentieth century.

The role of the state in economic planning was scrutinized after World War I and the socialist revolutions of 1917 and 1919. Industrialized warfare—total war—necessitated unprecedented government intervention in the economies of all warring nations. It demonstrated the coercive capacity of government to marshal the means of production, distribution, and exchange. Meanwhile, the Bolshevik Revolution consummated a long European tradition of revolutionary socialist thought and political agitation, legitimizing the wisdom of collectivist economic planning. The turn of the century also saw the rise of numerous emancipatory social and political movements, especially in Europe and North America, such as the Progressive movement in the United States and the labor and trade-union movements in the United Kingdom. Together, these forces elevated arguments for strong states and redistributive social policies, putting classical liberals suspicious of government on the back foot.

It was in this context that a specific discourse, “the socialist calculation debate,” emerged on the European intellectual scene. During the interwar period, political economists systematically clashed (largely in academic journals) over the feasibility of economic planning in a socialist system—specifically, over how a socialist government could determine prices for goods and services without the use of money and markets and in the absence of private property.

The debate turned on the specific claim that in a socialist system there would be no market prices for goods and services, and therefore no way to determine relative value, as such things require commercial transactions between private individuals pursuing their self-interests on the open marketplace. In the absence of market mechanisms, free-market thinkers contended, it’s impossible for central planners to allocate resources efficiently.

The Austrian political economist Otto Neurath was a colorful opponent of this proposition. His immediate post-World War I writings marked the beginning of the calculation debate (although the debate enjoys a rich prehistory). A polymath and leading figure in the Vienna Circle, Neurath asserted that the utilitarian logic of wartime mobilization demonstrated the superiority of central planning—and the obsolescence of private property, free markets, and money. “The tremendous transformations of the war,” he wrote in 1919, “have breathed new life into the idea of a utopia.” An “administrative economy” in which “money is no longer a driving force,” designed to “promote central control of all efforts and materials…in the interests of the people,” was on the horizon. In this socialized economy, central planners would engage in “calculation in kind,” or the practice of directly judging the value of resources or the desirability of large-scale planning without using any standard unit of accounting.

Neurath’s aim was to elevate considerations of social welfare over those of utility maximization. But he gave few indications of how state administrators could implement “calculation in kind” at scale, or how a complex economy would function without markets or money. It is unsurprising that he is especially remembered for his contributions to the philosophy of logic and science, as well as for his groundbreaking work as an inventor of infographic language systems. Although Neurath served as interim head of the Central Planning Board in the short-lived Bavarian Socialist Republic, where his reformist ideas were taken seriously by German policy makers like Walter Rathenau, he was dismissed by the German economist Lujo Brentano as a “romantic economist.”

It would not take long for someone to dispute Neurath’s “scientific utopian” vision on what they termed a “sound” economic basis. In 1920 the Austrian political economist Ludwig von Mises challenged Neurath with a paper titled “Economic Calculation in a Socialist Commonwealth.” A professor and economic policy adviser to the Austrian government, von Mises was a staunch classical liberal, a member of the so-called Austrian School who advocated fiscal and monetary discipline and cherished the moral and practical imperative of laissez-faire. He decried both socialists, who “conjure up a picture of the relentless exploitation of wage slaves by the pitiless rich,” and communist revolutionaries, who “invariably explain how, in the cloud-cuckoo lands of their fancy, roast pigeons will in some way fly into the mouths of comrades, but they omit to show how this miracle is to take place.”

Notwithstanding his arch anti-socialism, von Mises claimed his beef was not with socialism but with the technical mechanics of a socialized economy. In the absence of private property, markets, and money, he said, “rational” economic calculation was “impossible.” According to von Mises, if you dispensed with money you’d also dispense with the means to calculate economic decisions. He added that if prices emerge as a result of exchange relations, then abolishing exchange markets would preclude the process of price discovery and formation. Mises concluded that central planners would find it difficult to manage complex processes of production. With the means of production socialized, it would be impossible to calculate the relative efficiency of various factors of production, as these “production goods” would never be bought and sold on the open market. Therefore, central planners wouldn’t have enough information about their relative value and utility as industrial inputs. Socialist administrators would find themselves “groping in the dark,” managing “the absurd output of a senseless apparatus.”

Throughout the 1920s, socialist economists—at least those who found Mises’ arguments compelling—attempted to rebut the “Austrian challenge,” at least on theoretical grounds. In 1929 the American political economist Fred M. Taylor published “The Guidance of Production in a Socialist State,” in which he argued that in an ideal socialist state, “one in which the control of the whole apparatus of production and the guidance of all productive operations is to be in the hands of the state itself,” citizens could “feel assured” that state authorities “would be able to compute the resources-cost of producing any kind of commodity which the citizen might demand.” Taylor’s paper was formally impressive but not entirely reassuring, as it seemed to posit, rather than practically demonstrate, the ability of the state to substitute the functions of the market.

Then the stock market crashed, and the real world intervened. Determining what caused the Great Depression is the holy grail of macroeconomic history. Disagreement on the subject famously persists to this day. At the time, arguments that emphasized the anarchic tendencies of free markets as the cause of the calamitous downturn, and thus, the necessity of a more vigilant and activist state gained traction across Europe and North America. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal represented the most concerted effort of any developed nation to regulate big business, support the interests of organized labor, and provide for the general social welfare through increased government spending on social programs. In Britain, the Labor government led by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald established the National Economic Advisory Council, which was tasked with developing strategies for promoting economic recovery. With the winds of revolutionary communism at his back, Joseph Stalin implemented a top-down economic plan in the Soviet Union. And in Nazi Germany, the state imposed a complex system of trade and monetary restrictions to manage Germany’s relations with the wider world and control domestic prices, wages, private investment banks, and all other aspects of investment.

In this period, a few socialist economists engaged in the calculation debate began to incorporate neoclassical economic principles into their designs. This represented a significant shift in the socialist position—one not all socialists warmed to. From the neoclassical perspective, which gained coherence in the late nineteenth century with the work of British economist Alfred Marshall, supply-and-demand dynamics determined prices and patterns of production and consumption. Assuming that individuals rationally assessed the marginal utility (or simply the benefit gained) of their decisions, the economy could be modeled as a system of functional equations. Using mathematical formulas, these equations could be solved to address imbalances in supply and demand and steer the economy toward equilibrium. In a way, neoclassical ideas suffused socialist rationales for economic planning with a kind of mathematical and scientific authority.

Polish economist Oskar R. Lange refined the neoclassical position in his 1936 paper, “On the Economic Theory of Socialism: Part One,” which began with a bit of wry yet earnest flattery: “Socialists have certainly good reason to be grateful to Professor Mises, the great advocatus diaboli of their cause. For it was his powerful challenge that forced the socialists to recognize the importance of an adequate system of economic accounting to guide the allocation of resources in a socialist economy.” Lange described a theoretical form of planned economy that could, in principle, simulate the rational efficiency of a market economy. Though it was difficult to conceptualize, Lange harnessed a “trial-and-error” method developed in the 1870s by French economist Léon Walras to propose a scheme where a central government effectively “performs the function of the market.” Prices for “production goods”—i.e., raw commodities and resources like steel and wheat, which are used to produce consumer goods—would be fixed by a central planning board. Industrial production managers would then engage in quasi-market activity, buying and selling raw goods as needed, with predetermined production quotas (“the plan”) guiding their decisions. Monitoring this activity (somehow), government officials would adjust prices based on supply and demand until the market reached a state of equilibrium. In this quasi-auction-market simulation, Lange wrote, “the decisions of the managers of production are no longer guided by the aim to maximize profit. Instead, there are certain rules imposed on them,” regarding the types and quantities of goods to produce, “which aim at satisfying consumers’ preferences in the best way possible.”

According to historians Allin Cottrell and Paul Cockshott, the conceptual viability of “market socialism” (a term Lange never used) already had been established by the Italian economists Vilfredo Pareto and Enrico Barone in the early twentieth century, when they purportedly demonstrated “the formal equivalence between the optimal allocation of resources in a socialist economy and the equilibrium of a perfectly competitive market system.” Lange’s designs nonetheless seemed to constitute a fresh rejoinder to the strong Austrian School claim that rational economic activity under socialism was impossible. The Russian-born American–British economist Abba P. Lerner, a social democratic thinker who would go on to collaborate with Lange, agreed that socialist systems would benefit from incorporating market logic into their designs (as did the British economist H.D. Dickinson), arguing by the mid-1930s, “without the pricing system…it is impossible for an economic system of any complexity to function with any reasonable degree of efficiency.”

The neoclassical model of market socialism represented a partial concession to the proposition that market mechanisms are indispensable to the coordination of complex economic activity. Unsurprisingly, this conceptual development exposed an intra-socialist rift. For the Marxist economist Maurice Dobb, incorporating market principles into designs for a socialized economy was a contradiction in terms. Adopting the “competitive solution” only served to enshrine the principle of “consumer sovereignty,” which betrayed the collectivist ideal. Dobb was deeply suspicious of the analogy, drawn by free-market thinkers, between consumer choice and democratic choice.

Not only did Dobb critique the fetishization of possessive individualism and “exchange value,” the oldest of Marxian hobbyhorses, implied by the incorporation of market principles into a socialized economy. In his 1933 work “Economic Theory and the Problems of a Socialist Economy,” he assailed the “purely formal character of economic theory” in the neoclassical mold, anticipating a critique that economic theorists across the political spectrum would take up throughout the mid-twentieth century: that neoclassical analysis was a disinterested science that had become detached from reality. For Dobb, neoclassical economics had nothing to say about ends, only means. For his part, Lerner responded that Dobb—and Soviet Communists—held “superior contempt for the tastes and judgment of the masses,” who seem to “become more and more a recalcitrant material for the weaving of social patterns pleasing to bureaucratic aesthetics.”

In the mid-to-late 1930s, with the market socialist position firmly established, free-market thinkers shifted the debate onto fresh terrain. Friedrich Hayek, the Austrian free-market guru and admiring student of Mises, had weighed in on the debate in 1935 with Collectivist Economic Planning, a collection of essays (not all his own) on socialist economic thought and the status of the calculation debate. In “The Nature and History of the Problem,” Hayek criticized historical materialists for their faith in the inexorable rise of socialism, and in “The Present State of the Debate,” he claimed that the “central direction of all economic activity presents a task which cannot be rationally solved under the complex conditions of modern life.”

It was not until the late 1930s and into the 1940s, however, that Hayek refined what is often considered the ‘second line of defense’ in the Austrian position. In a series of articles published in Economica and the American Economic Review—“Economics and Knowledge” in 1937, “Socialist Calculation: The Competitive Solution” in 1940, and “The Use of Knowledge in Society” in 1945—Hayek moved away from arguments about the theoretical impossibility of rational accounting in a socialized economy, and instead emphasized the practical infeasibility of centralized economic planning, given the nature of knowledge and its dispersal.

For Hayek, the beauty of capitalism—indeed, the “marvel” of the invisible hand—was that unregulated interactions between private individuals and firms, each bringing to bear on their economic decision-making processes forms of “tacit knowledge,” produce a form of “spontaneous order” that no amount of planning could simulate. Economic historian Max Hancock explains that, for Hayek, “the dispersal of knowledge in society is so complete…and the mechanism by which order emerges from discrete transactions is so opaque, that it is not possible to possess a functional overview of the economy. Ergo, rational economic planning is an oxymoron, and socialists cannot hope to replicate the wisdom of the price mechanism.”

Hayek’s concerns about economic planning—and his scorn for the Promethean visions of socialist administrators and their economic theorists—were not without precedent. By 1932 Leon Trotsky had already lambasted the Soviet bureaucracy for imagining it “had at its disposal a universal mind” that could “register simultaneously all the processes of nature and society.” In some sense, Hayek’s position rested on an inverse but similar proposition: that market society itself constituted a universal mind; markets were capable of registering simultaneously all the processes of nature and society. The notion of “spontaneous order” was not entirely new, either. Such ideas had been espoused by luminaries like Adam Smith, David Hume, Bernard Mandeville, Jeremy Bentham, Karl Polanyi, and the Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou in the fourth century bc. In reality, as political theorist Bernard E. Harcourt explains, “the history of modern economic thought begins with the introduction of ‘natural order’ into the field of political economy in the mid-eighteenth century: the idea that economic exchange constitutes a system that autonomously can achieve equilibrium without government intervention.”

Hayek’s epistemological arguments complicated the case for economic planning and enriched the debate, but in the early 1940s, it still seemed as though market socialists had not been effectively refuted at the level of theory. The Austrian-born American economist Joseph Schumpeter, a heterodox figure famous for popularizing the term “creative destruction” to describe innovation engendered by entrepreneurship, concluded as much in his 1942 book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, in which he usefully narrated the debate.

Over the next thirty years the calculation debate settled into a somewhat abstract standoff. Hayekian free-market thought waned in influence, as the emergence of the ‘neoclassical synthesis’ in macroeconomics—a pragmatic combination of prevailing wisdom—gained acceptance among mainstream economists. During the Golden Age of Capitalism (1950–1970), British economist John Maynard Keynes’ ideas about the essential role of government in promoting economic dynamism and intervening to stabilize markets in crisis (liberal Keynesianism) predominated in global economic policymaking circles and deeply shaped the development of the post-World War II international monetary order.

By the mid-1970s the tide turned, however, and the debate became relevant again. In 1985—in the context of the ascendance of neoliberal thought across the globe, with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher carrying the torch of supply-side economics in ways that would define a generation—the economic historian Don Lavoie commenced a wave of revisionist histories about the calculation debate with Rivalry and Central Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered. Lavoie and other like-minded disciples of the Austrian School, such as historian Israel Kirzner, held that Mises and Hayek had never been effectively refuted. To them, neoclassical designs for market socialism were predicated on a static view of the economy that failed to account for dynamic adjustments that markets make in real time. Although economist Paul Samuelson could claim in 1989 that “the Soviet economy is proof that, contrary to what many skeptics had earlier believed, a socialist command economy can function and even thrive,” the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 seemed to suggest that planned economies were irrational. The dawn of post-Cold War globalization offered a somewhat unsatisfying coda to the debate: even if rational economic calculation within a socialist commonwealth were possible, centralized economic planning certainly seemed inadvisable.

For various reasons, scholars continue to return to the debate, which is now more relevant than ever. Some tinker at the margins, citing overlooked figures and dusty old papers that add fresh texture to the subject. Others consider this controversy as a source of inspiration. Still others fundamentally contest the legacy of the debate and continue to assess its enduring consequences. The political economist Isabella M. Weber has documented how the Austrian School—in particular, Mises’ ideas—influenced China’s “economic miracle.” The historian John O’Neill has applied Neurath’s ideas about “calculation in kind” in the context of ecological economics. Futurist Brett King and academic Richard Petty have exhumed the debate in defense of “technosocialism,” or the belief that effective central planning is increasingly possible given advances in digital technologies. The intellectual historian Tiago Camarinha Lopes has stressed that the debate always reflected a conscious effort on behalf of “capital-allied” champions of capitalism to “discredit” and “disable the rise of communism.” In this view, the debate “constitutes one of the most controversial and long-lasting episodes of class struggle within economic theory.”

Whether one puts great stock in the notion of class consciousness or not, the central lesson of the calculation debate is this: economics is a continuation of politics by other means. Even if Mises and Hayek insisted on the technical nature of their inquest, their position was deeply partisan. This goes for the socialists involved as well, who insisted with equal conviction on the impeccable rationality of their designs. At issue was never simply a disinterested dispute about the nature of rationality or the logic of computation. All participants in the debate maintained spoken and unspoken ideological commitments—to the metaphysical myth of spontaneous order or the Romantic anti-capitalist prophesy of proletarian revolution, and so on. It follows that anyone currently litigating the debate today is guilty of the same, whether they espouse the virtues of the libertarian minimal state or hope to hasten the dawn of “fully automated luxury communism.” Thus, for all its appearance as an academic diversion, the calculation debate had far-reaching consequences. We live and breathe each of them every single day.