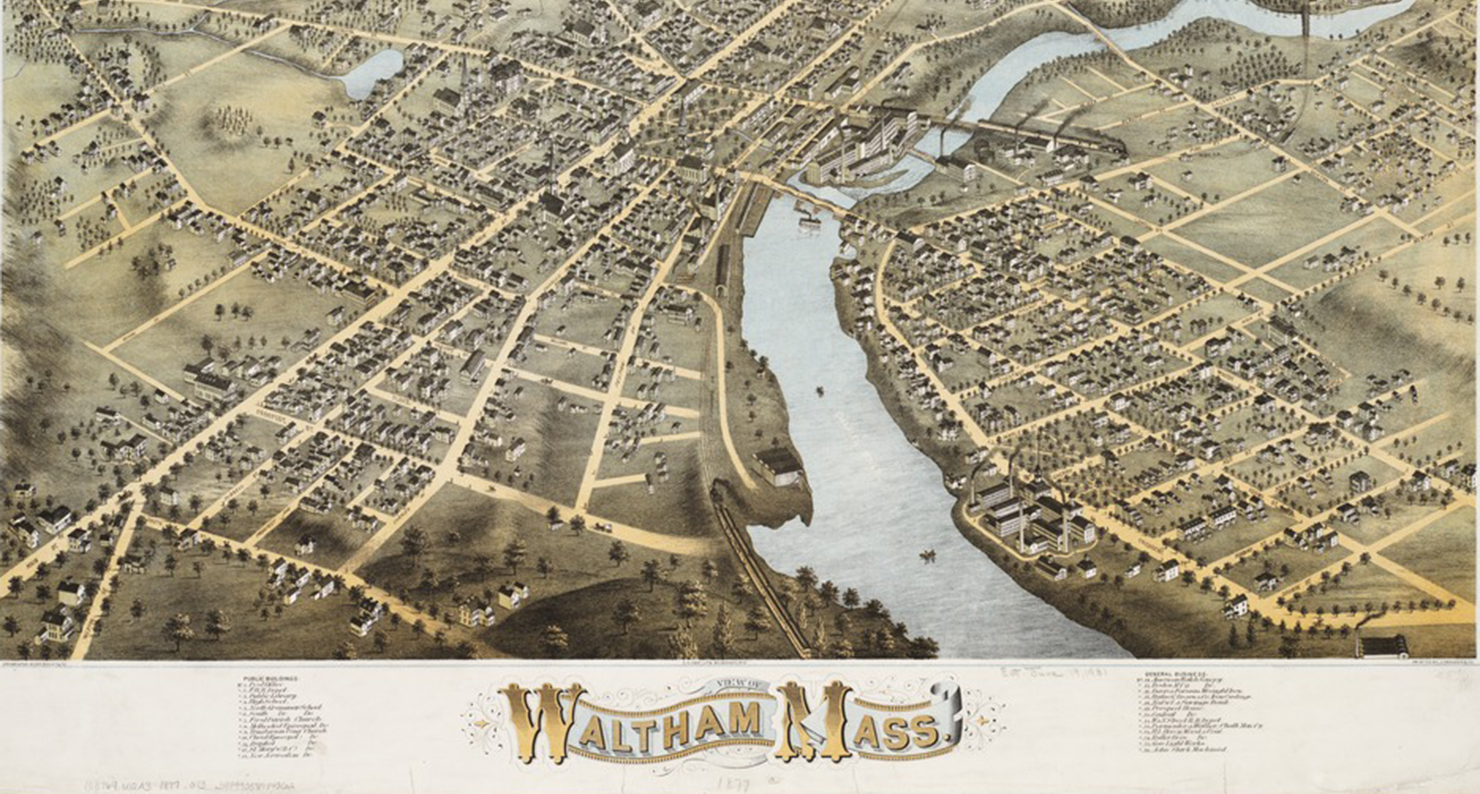

View of Waltham, Massachusetts, O.H. Bailey & Co., 1877. Boston Public Library.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

As long as it has existed, Waltham, Massachusetts, has been a place where outsiders quietly come and go. Bisected by the Great Road, it was once one of few stops on the journey west from Boston to the Massachusetts frontier, nine miles out from the city along a series of wooded brooks that roll into the slow current and wide turns of the Charles River. When I moved here fifteen years ago, people called folks like me a “breezer”—anyone who is not from here must just be breezing through, heading somewhere else, as if Waltham were still a village way station.

In the center of town there is a little hill traversed by a street named Mount Pleasant, and I live at the top. At the foot is a house with pale-blue wooden shingle siding, vaulted on a high stone foundation. Built around 1840, it was first occupied by a man named Samuel Locke, his wife Harriet, and their young son.

At the other end of the lane, Mount Pleasant runs into a street named Liberty. A house surrounded by flowers and fruit trees once stood where Liberty opens onto the bustling Great Road, now called Main Street. A man named Jarvis Lewis lived there with his family while operating an apothecary shop out of the front room.

In Locke’s house a long-forgotten pictorial monument hints at the past life at Liberty and Mount Pleasant: breezers who set down roots in the neighborhood, did something radical, sustained it for a generation as if it were routine business, and then went back about their lives without fanfare. On the walls of a modest third-floor loft (likely occupied by Locke’s son), dozens of printed engravings from Harper’s Magazine form a kaleidoscopic collage depicting the daily triumphs and tragedies of the Civil War. Like the walls of a prehistoric cave, portraits, battles, and cartoons weave together, resonating with the overwhelming tale of conflict that surrounded the everyday events of the residents’ lives.

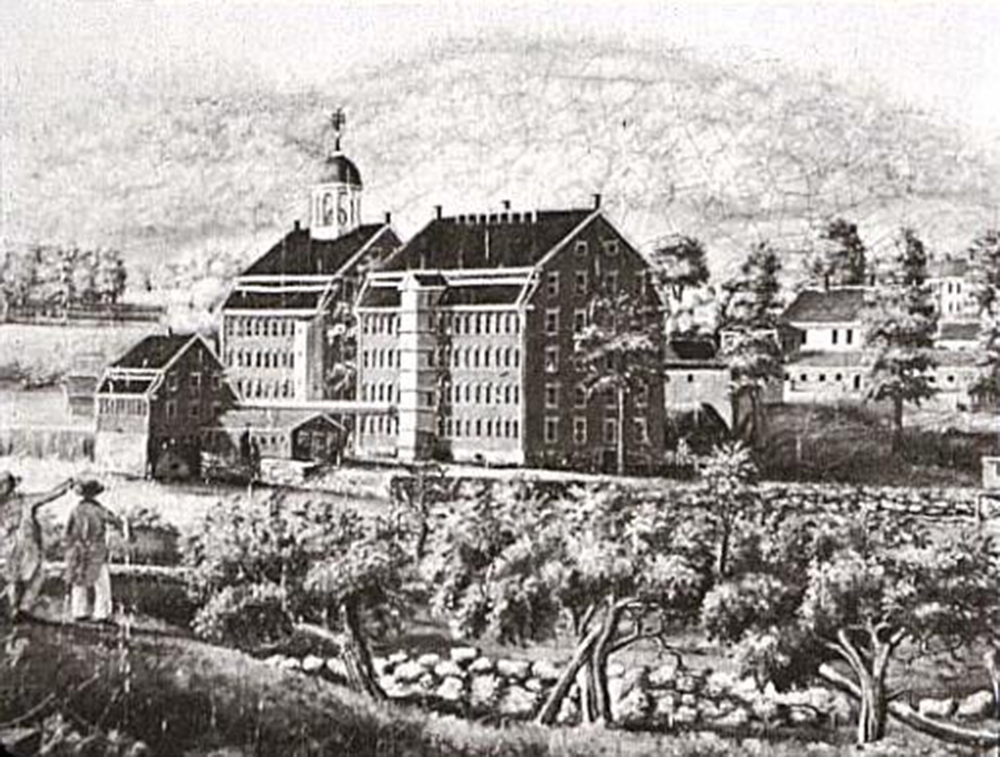

The Waltham that Jarvis Lewis and Samuel Locke came to in the early 1840s was shaped a generation before their arrival by the merchant-inventor Francis Cabot Lowell. Along with a close-knit group called the Boston Associates, Lowell had set off the American Industrial Revolution at a nearby mill along the river. Waltham was the first industrial center, but unlike the empire of rigidly managed compounds that spread along the more powerful rivers of New England after Lowell’s death in 1817, it was not a company town.

With the opening of the mill in 1814, the town was transformed from a hamlet into a village with a vibrant social life. Mill-related associations, often initiated with non-mill townspeople, included a dance group and a speaker series. Even a lending library was created, an uncommon institution for the time.

With more people in Waltham and a religious revival sweeping the nation, the First Parish Church took a special place in town life. At the heart of it were the sermons: a source of entertainment as well as an exercise of authority, they had the power both to break and to mend the community. In one 1812 sermon, town minister Samuel Ripley delivered a screed in opposition to the impending war with the British. The immediate consequence of his foray into politics was the loss of fifty-five parishioners, who stormed across the road and formed the Second Religious Society. It was a rift that would never be fully resolved.

A hard man, Ripley did everything he could to eke out a living on a small salary with increasingly diverse parishioners and unprecedented demands. At the same time, he had to tend to his struggling extended family. In 1811 his half-brother William died of tuberculosis at the apex of his career as minister of Boston’s First Church. Ripley helped ensure that William’s children did not starve. One nephew was sent to study law with Daniel Webster. Another helped teach at the church school in Waltham and gave his ordination sermons at his uncle’s pulpit. After delivering them in the fall of 1826, young Ralph Waldo Emerson boarded a coach to Boston. A fellow traveler turned to him and said, “You’ll never preach a better sermon than that.”

By the 1830s a conventional town center began to take shape along the Great Road. A man named S.B. Emmons arrived and started a newspaper called The Hive. He had it printed first in Boston, and then later at the local print shop, opened along the Great Road by another recent newcomer named Josiah Hastings.

In a company town, Emmons and Hastings would have had a hard time with the company men if they ran an independent newspaper. In Waltham, they printed what they liked, which mostly fit the tastes of the somewhat conservative, pious townsfolk. Aside from one small notice posted in many issues, little would have ruffled local feathers. That notice offered access to a library of antislavery volumes at Hastings’ Print Shop, come one, come all.

The words antislavery and Massachusetts were far from synonymous in 1835. The Virginia slavery debates that set in motion the South’s ideological doubling-down on the virtues of the institution had only recently occurred. Massachusetts had outlawed the practice half a century earlier, yet even in the 1830s attitudes about slavery among many Yankees ranged from indifference to tacit support.

To that end, abolition was not openly or widely espoused in town at the time. The average Walthamite’s interest in race was likely confined to such topics as the inferiority of the Irish, their plans to immigrate to the United States, and their plots to overthrow the country with support from the Pope. Emmons shared such beliefs about the Irish, but his readers may not have shared his about abolition. His paper shut down in early 1836.

At least one local abolitionist was notably passionate, however, as shown by an article in another 1834 publication. William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the nation’s leading antislavery newspaper, The Liberator, had noted with satisfaction the formation of a Waltham Antislavery Society that spring. With much of Boston opposed to abolition—a mob would try to kill Garrison for speaking there in 1835—Waltham was becoming safe ground, albeit quietly, for organizing antislavery activity. Meetings were held at a tavern along the Great Road.

At first glance the notes that the society filed with The Liberator could fool one into thinking the group cared mostly about accounting for dues. In reality, they quickly went much further in their opposition to slavery than simply passing a collection plate. In November, The Liberator ran the following letter:

Dear Sir,

Supposing a slave makes his escape from his master, and comes in Waltham, and I assist him in getting still further from his master, so that he finally gets to Canada, or any where else beyond his master’s reach; can that master recover, at law, the amount of the slave from me, provided I am worth it?—i.e. have I, or have I not, a lawful right to assist a runaway slave retain his freedom?

An answer to this enquiry, either by letter directed to D.M.G. of Waltham, or in the next week’s Liberator, will be received with favor by a friend of all humanity.

Dodging the pragmatic particularity of the question, Garrison acknowledged that the issue raised by the so-called Waltham correspondent was entirely novel and had “never been submitted to any judge or jury in New England.”

Around the time I moved in at the top of Mount Pleasant, a new family moved into Samuel Locke’s house at the foot of the hill. We chatted from time to time, talking about how so many of the residents had lived on the street for generations. Their house had been run as a boarding house by nuns for nearly a century.

It was a strange place, they told me; odd old things remained. They invited me to look at their third-floor room. It was different, they said—there were newspapers on the walls. Climbing staircases with high steps and low ceilings, I went inside, the beams and planks widening as I neared the loft.

At the top of the stairs, a small window cast daylight across the room, the smokestack of the mill rising up over Main Street. The engravings published in Harper’s Magazine during the Civil War that completely papered the walls had been meticulously cut and pasted. Sepia tones blended the prints together—ships at sea cascading into grand dances for elite officers of the Union Army, rolling out into the howling sad hills of battlefields, war plans, charges and retreats. I had never seen or heard of anything like it: a multidimensional visual representation of America during the war. The walls seemed to move, the hundreds of thousands of finely etched lines pulling the tiny room up through the ceiling, as though it were immeasurably larger than it appeared.

By the early 1840s newcomers were moving into the town center that had taken shape over the previous decade. They were the first industrial middle class in America, and they took up the mantle of innovation begun three decades earlier. They moved beyond the mill and went into business and government. They joined local societies and sat in the same pews as mill folks and mill owners. To accommodate their activity and hasten the ease of getting around, they built roads.

A row of stores was built across from the print shop. In 1843 a man named Lewis Smith constructed the suggestively named Liberty and Mount Pleasant streets, passages to his large tract of land; land he steadily split up for houses and churches of various denominations.

I learned, to my surprise, Mount Pleasant Streets are often so named in homage to the abolitionist town of Mount Pleasant, Ohio. In the early part of the nineteenth century, a newspaper was started there with support from the town’s Quaker population. They were among the earliest white Americans to protest slavery, and they put their money where their mouths were. As piously vicious as Melville’s Nantucket whaling Quakers, many had given up farms in the South, told slaveholders to go to hell, and headed north to states like Ohio. Their newspaper was their broadcast to the outside world. The town name became synonymous with abolition.

Smith’s housing development attracted such people. Belonging to women and men alike, the neighbors’ names rise up as hosts, participants, and authors in the antislavery literature of the time. A commingling of ministers, tradesmen, and politicians, among others, they led an increasingly public tide of organized opposition to slavery. They were comfortable abolitionists.

Sylvanus Cobb, a Universalist minister, began publishing the radical newspaper The Christian Freeman and Family Visitor out of Hastings’ shop. The incoming Unitarian minister, a mathematician named Thomas Hill who later became president of Harvard, published a collection of antislavery poems just prior to arriving in Waltham. Samuel May, uncle of novelist Louisa May Alcott and president of the Antislavery Society of Massachusetts, presided over protests and celebrations in the town. Speakers of national renown visited with increasing frequency.

Letters sent to Cobb, recounted in his son’s 1867 memoir, reflect the more common beliefs of the rest of the nation regarding abolition in the early 1840s. “Dear Sir,—When I subscribed for your paper I supposed I was going to have a real good Universalist paper, as I knew that you were one of the best preachers in the country…But I find that I was sadly mistaken…I cannot stand your stuff about Niggers!...so you may stop my paper. I have paid up to next May, but you may send the rest of the papers that it should get to somebody that loves the Niggers better than does Yours truly.”

In 1842 the matter of harboring escaped slaves, raised in part by the “Waltham correspondent” who had written to Garrison years earlier, now hit the state with thunderous effect. A runaway slave named George Latimer had made his way to Boston, where he was arrested for larceny and ordered held. Fearing that Latimer would be returned to the South, his attorney Samuel Sewell appealed for a jury trial, where he expected that Latimer would go free.

The case was heard by the chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, Lemuel Shaw, who was ardently opposed to slavery. Yet Shaw shocked the state by ruling that Latimer’s fate was a matter of federal law and Latimer could be sent back. Protests erupted; the tide of opposition to slavery was growing. A gathering was called at the Methodist Church in Waltham, in order to “take into consideration the encroachments of slavery on our laws and liberties, and to take measures that we, in Massachusetts, may be rid of it.”

Ripley presided over an audience of almost five hundred people who signed an antislavery petition demanding Latimer’s release. Garrison later noted, “Waltham had a stirring meeting, and is doing well.” Such action was not without its risks, especially for Ripley. The mill owners had an interest in ensuring a steady flow of cotton to the north, which meant they had an interest in slavery. Most owners attended Unitarian churches like Ripley’s, and they were not pleased with abolitionist activity taking place in their own backyard. They were known to exert tremendous pressure on abolitionist ministers. During a later fugitive slave crisis, Garrison wryly remarked that it was more common to expect that the bell of Waltham’s “Unitarian Church being clogged with cotton would not sound.”

Though the cotton men had spread their networks across the nation, the abolitionists living alongside them at Waltham were able to act independent of their wishes. Unlike their brethren in company towns, Waltham’s tradesmen and their families held comfortably secure roles in most city institutions. They led the board of the local bank; pushed to bring the railroad through town; bought, sold, and developed the city center.

More piously technocratic than peacenik, this business class transformed Waltham. Their work laid the foundation for the town’s purchase of a massive tract of land across the river, doubling the size of the village center. The purchase led to the arrival of the Waltham Watch Factory, which made the first mass-produced watch. The iPhone of its day, it was responsible for mechanizing the movements of the Union Army during the Civil War.

In the wake of the Latimer affair, the Waltham abolitionists rallied. Frederick Douglass delivered an address there in 1844. August First Celebrations, the first significant nationwide gatherings to ritualize opposition to slavery, drew thousands to a grove along the river. In August 1845 Emerson returned to deliver an antislavery talk, his first outside his hometown of Concord.

He singled out the mill owners, exhorting the audience to see the persistence of slavery not just in southern plantations but also in the actions of the Associates, whose businesses encouraged the slave system with insatiable demands for raw cotton. Support for slavery, he said, “acts in certain places. It acts on the seaboard, and in the great thoroughfares, where the northern merchant or manufacturer exchanges hospitalities with the southern planter, or trades with him, and loves to exculpate himself from all the sympathy with those turbulent abolitionists.”

A relative of Sylvanus Cobb’s, Locke came to Waltham in the 1840s, moved in at Mount Pleasant, married, and had a son named Alonzo. I searched the town archives for Samuel but found only a few facts. A religious man, he hosted the ratification of Articles of Faith and Covenant for the Universalist Society of Waltham in his parlor, and later served on the first board of directors for the town library. On the day Waltham acquired the land across the river, he wrote a vigorous endorsement for cod liver oil in the town newspaper. In a directory, there is mention of his job, heading up the city’s newly built gas works.

Born in 1847, Alonzo came of age as the nation, including his neighborhood, went to war. Always in poor health, he nevertheless attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and then returned to Waltham, where he became a respected mechanic and led the local Masonic lodge.

At the end of the war, Alonzo would have been around seventeen, so I looked to see if he had joined the Union Army. Instead I found a small folder of papers covered with a handwritten note about a man whose name I vaguely recognized from the documents I had read—Dr. Jarvis Lewis.

A doctor only in the parlance of the time, Lewis was more of a druggist and had built his house at the corner of Liberty Street, across from Hastings’ print shop. A leading abolitionist, he had led the drafting and signing of Waltham’s petition for Latimer’s release, alongside the Reverend Ripley. He and his wife were also occasional contributors to The Liberator and clearly knew Garrison. Samuel May presided over their wedding.

Collected by a town historian, the note was written in the early 1900s by Lewis’ daughter Helen, and it describes their home. A little girl in the 1840s, she would have known her neighbor Alonzo Locke. (The historian prefaced the note with a comment that Helen wore attire from the Civil War for her entire life.) First she described the yard and then the entire house, room by room. Then she wrote:

It was said that Liberty Street was so named because Mr. Lewis Smith & Dr. Lewis were such strong abolitionists. The house was one of the stations on what was called the Underground Railroad, a plan for helping runaway slaves to escape. They were sent out of Boston hidden in the backs of carriages, & left at the houses known to the initiated. To be kept out of sight in the daytime, & sent on to Concord by night, on their way to Canada where they were safe. At one time a colored family was here for a few days. At another time Dr. Lewis was at an Antislavery Meeting in Boston, & before his return in the evening, a colored man came to the back door, saying he had been sent here. He was let in, rather fearfully, by the women folks. But it proved all right. There were other cases not so well remembered. The work was attended by the risk of fine or imprisonment, but fortunately the house was never searched by slave owners or their agents. & the owner was never arrested though an active worker in the cause.

Armed with photographs of the walls at the Locke house, I sought an expert who could help me make some sense of the world that surrounded the room at Mount Pleasant. I was led to John Stauffer.

Stauffer is a man who should be photographed only in daguerreotype. He has hair like John Brown’s, as though he runs his fingers through it, pulling it straight up without noticing. A leading expert on images from the Civil War, he invited me to his Harvard office to discuss Locke’s third-floor room.

Seated beneath a photograph of Frederick Douglass, Stauffer handed me a scrapbook. With a gentle, raspy, singsong voice, he paused at a Harper’s Magazine image to explain that Harper’s was the cinematic powerhouse of imagery during the war. The magazine’s importance in creating a uniform vision of immediate events, across the entire nation, was unprecedented. People saw war for the first time. Its sway was such that a full spread of dead Union soldiers published in their pages horrified the public to the point that it almost turned the North against the war.

During Reconstruction, emancipated slaves papered simple rural homes in the South with newspaper images from the war—memory on the walls. But the room at Mount Pleasant did not look the same as those rooms. Stauffer could think of nothing like it ever found in the North. “It’s sweet,” he said, and I got the sense that he meant it in the saddest, most expansive sense of the word.

I asked him about the Underground Railroad, mentioning Helen Lewis’ account, but Stauffer said it was a fad in the early 1900s to say your family had harbored runaways. Then he closely read Helen’s note and seemed to think twice. Quietly and calmly, he said, “That seems much more authentic.”

Alonzo Locke was around thirteen when the war began. Stauffer and I visited the room at Mount Pleasant together, and as we stood there it seemed most likely that it was Alonzo’s handiwork, a boy’s imagination reflected through the pages of popular culture, pinned up just as children memorialize the wins of athletes on walls today. I pointed Stauffer to an image of Nathaniel Banks, Waltham’s now-forgotten favorite son. Unlike other politicians of his day, Banks was not from the elite. He worked at the Waltham mill and his school debts were wiped clean by his teacher the Reverend Ripley.

A political opportunist, Banks became the first Republican Speaker of the House and then governor of Massachusetts. During the war, he was exiled to manage the Union’s occupation of New Orleans after he forfeited the Army’s commissaries to Stonewall Jackson in a humiliating rout. It is said Mary Todd Lincoln distrusted him, and he was kept from serving in Lincoln’s cabinet. Here none of that is visible. Alonzo has placed an engraving of Banks in full uniform, the regal hometown hero among the pantheon of mythic figures and events of the war.

The most famous images of the war are here, including the searing July 4, 1863, engraving of the lashed back of Gordon, “A Typical Negro.” Crouched in front of the wall, Stauffer stopped at a sea battle scene where someone, perhaps Alonzo, had colored the explosions that light up the sky. Nearby—next to the tall, thin visage of the unfortunate Mexican emperor Maximilian—is a cartoon about a little boy drowning. Every image is neatly cut, fitted, and pasted.

Back on Mount Pleasant Street, I asked Stauffer if he knew of Henry Warren, and he lit up. Warren was the last man to photograph Abraham Lincoln, two days after the Second Inaugural Address. I told him that Warren’s studio was right below us on Main Street, a block from Jarvis Lewis and the Lockes, alongside the dry goods store of Newell Sherman, another of the town’s ardent abolitionists. I added that there’s a particular Warren photograph I love more than all the others I have seen.

A group of people stand in front of Hastings’ print shop. I imagine one of them is Hastings himself. The road is laid out before them, two houses perfectly appointed, white with a picket fence. The caption says, “Printing Office and Residence of Josiah Hastings, Waltham, Mass.”

It is a typical image, plain and simple. Common. It could be anyone, anywhere, pausing for a photograph and moving along. The ordinariness of it is its theme. Regular, working, middle-class tradesmen, doing what they do, unimpeded and anonymous among countless similar photographs of daily life. On any given day in that neighborhood during the mid-1800s, you could stop at the print shop for the paper, get your groceries at Mr. Sherman’s, have your portrait taken by Mr. Warren, pick up your medicine from Dr. Lewis, and go to church with Mr. Locke. A comfortable life, among comfortable people, some of them from here, most of them not, every one of them going about their routines. Nobody in a hurry. No danger that someone is just passing through. Not even worth a second thought. Nothing extraordinary to see here.

Explore Home, the Winter 2017 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.