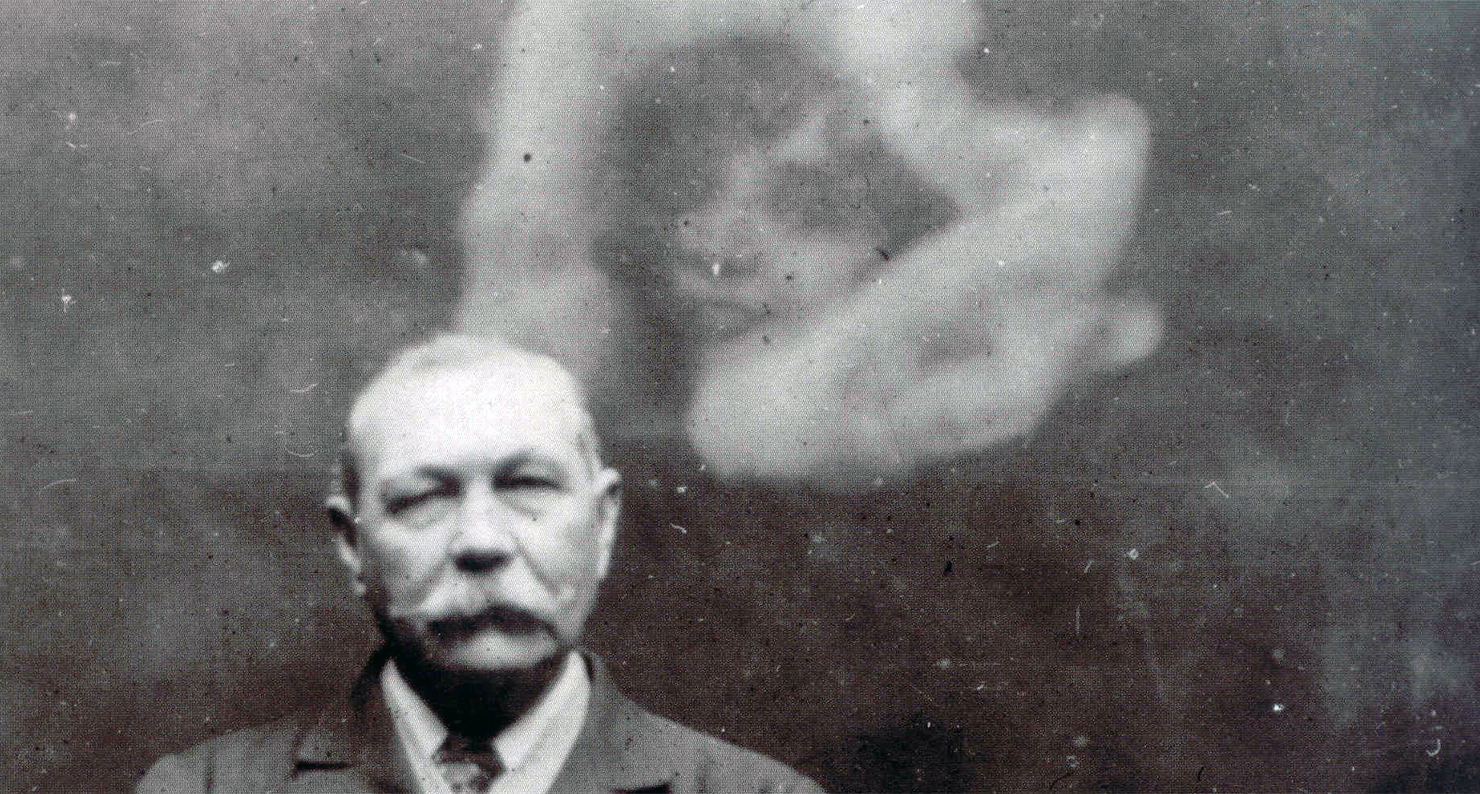

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle with psychic extra, c. 1922. Barlow Collection, British Library London.

“How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?”

—Sherlock Holmes, The Sign of the Four (1890)

In “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual,” an 1893 Holmes story that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle ranked among his best, our hero deduces the practical significance of an apparently nonsensical poem. Passed down from the seventeenth century, the lines of the Musgrave Ritual pose a meaningless riddle to its familial heirs until Holmes, on the trail of a missing maid and butler, recognizes them for what they are: a treasure map. That Conan Doyle’s celebrated detective could pluck salient information from murky verse is no surprise. In the Musgrave case, a confusion encodes an answer, aging traditions point to solid truths, and both are clues to an even more baffling mystery: how the creator of literature’s most logical detective became utterly seduced by magic.

Throughout his escapades, Sherlock Holmes’ reliance on ballistics and other cutting-edge forensic techniques shattered folk wisdom and transformed skepticism into progressive ideal—you can see it in the friction between the detective and any daffy constable who dared upset his crime scene. Conan Doyle, a Scot, may as well have channeled countryman David Hume in producing a man precisely attuned to the oddities of cause and effect. We remember Conan Doyle, however, as a author burdened by his popular alter-ego, attempting to kill Holmes off in “The Final Problem” because he thought the detective a lowbrow distraction. “He takes my mind from better things,” he wrote to his mother in 1891, when toying with the idea of Holmes’ demise.

But just how incompatible were the temperaments of Conan Doyle and his most enduring character? To the lay observer, Holmes’ feats of logic can appear magical. “You know a conjurer gets no credit when once he has explained his trick,” he explains in A Study in Scarlet, “and if I show you too much of my method of working, you will come to the conclusion that I am a very ordinary individual after all.”

Perhaps the ordinary was just too painful for Conan Doyle. Many draw a connection between his zeal for the supernatural and his despair following the deaths of his son Kingsley and brother Innes by influenza in the closing days of World War I—two passings among many in his family over the course of a hard dozen years. The hope that we may contact the dead via séance (which Conan Doyle allegedly did) is enough to test even the most rigid materialism; the Great War itself, full of senseless attrition and biological atrocity, was a trauma that prompted a search for answers. Conan Doyle would write eloquently about his doubts in the supremacy of science and his stirring sense of a world outside its grasp:

Victorian science would have left the world hard and clean and bare, like a landscape in the moon; but this science is in truth but a little light in the darkness, and outside that limited circle of definite knowledge we see the loom and shadow of gigantic and fantastic possibilities around us, throwing themselves continually across our consciousness in such ways that it is difficult to ignore them.

Such is the tone of The Coming of the Fairies (1922), which takes a broad survey of the unexplained in nature but mainly serves to reproduce and argue the veracity of the Cottingley Fairy photographs, five ethereal exposures taken by young cousins Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths that show the girls at play in the woods with winged sprites. The first photos surfaced in 1919, when Elsie’s mother brought them to a meeting of the Theosophical Society, an umbrella covering all manner of occult and paranormal interests, with the loose objective of universal fraternity. Edward Gardner, a leading member, seized upon the photos as key to an expanded definition of reality. It was excellent luck as well for Conan Doyle, who had already been commissioned to write an article on fairies for the Strand Magazine when an editor at Light, a spiritualist journal, related the discovery.

For all his scientific flair, photography was one innovation Holmes never relied on. “As a rule,” Holmes tells Watson in “The Adventure of the Red-Headed League,” “when I have heard some slight indication of the course of events, I am able to guide myself by the thousands of other similar cases which occur to my memory.” Indeed, we tend to imagine Holmes as a camera in his own right, lensed with a magnifying glass, able to retain trace data (“trifles,” as he calls them) for cross-reference in some mental databank. He knows the eye can play tricks, and that witnesses can distort the facts of an otherwise rigorous investigation.

How, then, could Conan Doyle think that the Cottingley Fairy photos were anything other than spirited fakes? Not even amateurs took them for genuine. The fairies were hat-pinned cardboard imitations—drawn by Elsie, a talented artist—from Claude Shepperson illustrations featured in Princess Mary's Gift Book—a compendium of fantastic tales that included a Far East story from, of all people, Arthur Conan Doyle. In a 1985 television interview on Arthur C. Clarke’s World of Strange Powers, an elderly Elsie and Frances confessed to their accidental hoax, with Frances remarking of Conan Doyle and other believers, “I can't understand to this day why they were taken in—they wanted to be taken in.”

The time was ripe for fairy madness, for opiate innocence in an industrial wasteland. Conan Doyle gave well-attended lectures on both sides of the Atlantic that spelled out his views on ghosts and other intangible phenomena. He suggested the Cottingley fairies might be visible only to Elsie and Frances due to a gulf between different orders of psychic “vibration,” a hypothesis shockingly akin to theoretical physicists on the topic of string theory. Like any dedicated UFO-hunter, Conan Doyle stressed that many debunked accounts do not disprove a grander pattern. It was something Holmes recognized as well. “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data,” the detective remarks in “A Scandal in Bohemia,” adding, “Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

Conan Doyle did the latter in a way that meant to resemble the former—making eclectic spiritual atmospheres accountable to empirical ones. Of course, we’ll never have all the data. An apropos line from A Study in Scarlet: “The theories which I have expressed there, and which appear to you to be so chimerical, are really extremely practical—so practical that I depend upon them for my bread and cheese.” It is tempting, then, to see something of P.T. Barnum in Conan Doyle’s convictions: a sensational attempt to move past Sherlock Holmes and towards The Edge of the Unknown, his investigation into psychic activity. But a letter written to Elsie’s father in 1920 is nakedly earnest and makes clear his long-held beliefs: “I have seen the very interesting photos which your little girl took. They are certainly amazing. I was writing a little article for the Strand upon the evidence for the existence of fairies, so that I was very much interested.”

A strange addendum to Conan Doyle’s spiritualist career was the publication in 1983 of an article called “The Perpetrator at Piltdown,” by John Winslow and Alfred Meyer. The Piltdown Man was elaborate evolutionary hoax—supposedly the oldest human fossil ever dug up. In 1912, a skull and several bone fragments were found by an archaeological hobbyist at an excavation pit several miles from Crowborough, where Conan Doyle lived at the time. A lower jawbone was later shown to be an orangutan’s, and chemically aged (an alchemic bit of magic in its own right), with the molars and canines filed to suggest a missing link between ape and Homo sapiens.

The article presented an admittedly circumstantial and mischievous argument that Conan Doyle had the opportunity, skill and motive—a literal bone to pick with the scientific establishment—necessary to implicate him in the planting of Piltdown Man and other suspect “Paleolithic” finds at the site. It’d be a scientific revenge worthy of Professor Moriarty, and Conan Doyle was an accomplished prankster. But a deception of those on a quest for ultimate truth doesn’t quite fit an author who pined for the flourishing of methods for deconstructing wonders whose very shape we cannot apprehend.

Which brings us back to a touching correlation between Holmes and his creator. The detective, while often a dispeller of superstition, was above all open-minded, willing to believe in what lies beyond our common perception at the very moment it became necessary to do so. What was impossible for Conan Doyle was that pure reason had covered the entire terrain of things, overturned every stone. His efforts were sincere and dogged; he was Sherlock Holmes in fairyland. In his diary, novelist Hugh Walpole marked July 8, 1930, with an epitaph: “Conan Doyle dead. A brave, simple, childish man."