Boston Harbor, by Charles Manger, c. 1869. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Mrs. George Viault, 1970.

In the years immediately following the Civil War, the federal government sent hundreds of freedpeople from Virginia and Washington, DC, to Boston. This massive relocation project was carried out by the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands—the Freedmen’s Bureau—established by Congress in March 1865. Conceived as a way to address the human misery endemic to southern refugee settlements, a bureau transportation program sought to funnel Black servants into white households. Presumably these formerly enslaved people now scrounging for work in a town or in the countryside would find plenty of wage work (as domestics) once they disembarked on a Boston wharf.

The program consisted of two overlapping initiatives: one, out of Washington, overseen by General Charles H. Howard from 1866 to 1869 (his brother General Oliver O. Howard served as bureau head); the other, out of Fortress Monroe (and Norfolk, Richmond, Petersburg, and Hampton), coordinated by General Samuel C. Armstrong during the same years. Between May 1866 and December 1867, as a part of the latter effort, the bureau paid the tickets of 579 freedpeople bound for New England, mostly to Massachusetts, and most of those to Boston. About three-quarters of the migrants were between twelve and twenty-five years old.

During the war, the Virginia Peninsula proved a reluctant host to thousands of Black refugees streaming in from nearby areas as well as from other states. Many endured crowded, chaotic, life-threatening conditions in temporary, makeshift camps. Nevertheless, formerly enslaved people gradually created freed communities, drawing upon limited resources to organize churches, build schoolhouses, and search for long-lost loved ones. Poverty afflicted almost all: some families continued to live in the slave quarters and work the land of their former owners, now as renters, while others squatted on abandoned property only to be displaced by Union troops or civil authorities. Among the most pervasive forms of labor exploitation was wage theft—a white employer’s refusal to pay a Black person’s wage after an agreed-upon task was completed. In the words of Worcester’s Sarah Chase, now working at a hospital in Richmond, “Not a few hard workers are growing thin and weak by trying to live on promises to pay,” and even those who could find jobs such as coal-heaving were forced to subsist on “a dinner of half-baked corn bread and coffee.”

With the approval of local judges, white landowners “apprenticed” freed children, virtually enslaving them, running roughshod over the protests of parents. Bureau agents sent orphans to orphanages despite the offers of relatives to care for them. Whites sought to continue to profit off Black labor, but they had an aversion to Black political activity and schooling; their resentment triggered random physical attacks on individuals and the burning of Black schoolhouses and bureau offices.

Local almshouses were overwhelmed by the crush of refugees; civil officials expressed contempt for the in-migrants, described as a “very large destitute colored population not legitimately belonging to us, and we have no power under the law of removing them.” Bureau rations and northern donations of shoes, clothing, and blankets were unequal to the need. In Washington, refugees took shelter in huts that afforded no protection from the elements and found themselves preyed upon by pawnbrokers offering easy loans. It was not surprising, then, that the bureau saw as one of its major functions the swift reduction of the local Black population. Officials focused on sending freedpeople not only to the North, the South, and the Midwest, but also to their former homes. Pressured to leave, many hesitated to go north. According to Charles Howard, families wanted to provide for themselves, but “the cold is a bugbear and the fact is that they are totally ignorant of that part of the country and its people, making them prefer the hard lot here to the uncertainties and apprehended evils of going away.”

The bureau transportation program combined a hardheaded assessment of local demographic conditions with an idealistic fervor. General Armstrong possessed a strong moralistic streak. Born in Hawaii of Presbyterian-missionary parents, he believed that the program was essential to the reconstruction of the South and the well-being of the refugees—a boon to those who stayed behind as well as to those who left. In the summer of 1866 he encouraged local bureau agents to scour the countryside around Hampton and advertise the program widely, in order “to use every effort to induce those, especially females, to remove to Boston”; he was interested in finding “indigent or unemployed freedpeople, who are already or are liable to become dependent upon the Bureau for support.” He discouraged agents from rounding up the poor indiscriminately, however: each person granted transportation should be a “person of good character and honesty.” No doubt some might apply “for the most improper purposes”—a reference, perhaps, to those who would take advantage of the bureau’s goodwill and then prove to be malingerers or, worse, prostitutes. In sum, “As getting homes in the North is believed to be an excellent thing for the freedpeople, it is hoped that no effort will be spared to make this enterprise a success.”

In sending people north, bureau officials relied on a mix of requests for workers from individual northerners and standing orders from contacts, such as operators of “intelligence” (employment) offices. Civilian labor agents were crucial to this relocation effort, and rivalry among them was fierce; in the DC area, one Boston agent competed with twenty other people seeking a commission for each person they could get on a train or steamship.

Requests came into the bureau from a variety of prospective Boston and area employers—bank managers, lawyers, judges, physicians, mayors (of Lawrence and Chelsea), hotels, warehouses, furniture dealers, milliners’ shops, merchants, and owners of dry-goods stores, among others. Fifteen-year-old William Smith went to Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, though it is uncertain whether Agassiz put him to work as a servant or forced him to participate in some kind of “scientific” experiment related to “race.” A goodly number of the wealthy men and women requesting freedpeople already had live-in Irish servants working for them; some of these employers were looking for a cheaper alternative, some wanted to rid themselves of Catholics in their household, and others saw Black workers as objects of charity.

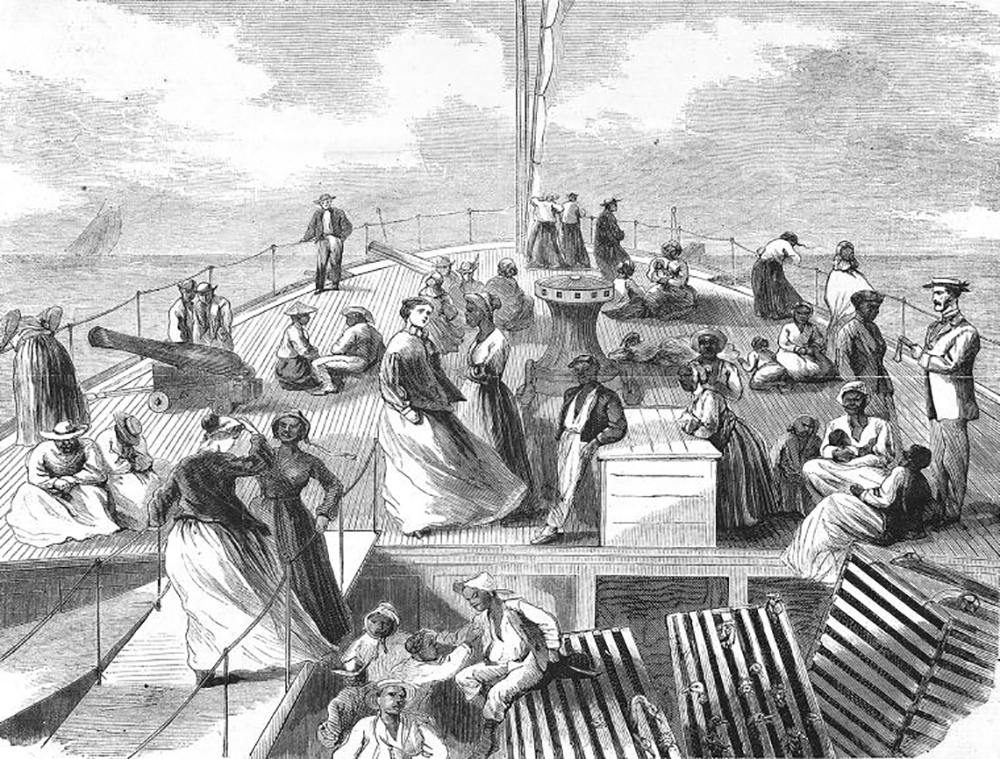

The four- or five-day journey north was fraught from beginning to end. Migrants usually traveled via regular schooner service, which ran on Tuesdays and Saturdays starting from Richmond or Norfolk with stops at Fortress Monroe. At times family members ended up going separately, when some in their party got lost on the way to the dock or a particular ship’s passenger list was full. More than one person landed in Boston only to learn over the next days and weeks that close kin had had a change of mind and decided to stay in Virginia. In some cases, passengers stopped in New York City, a layover that caused its own problems. Once a ship anchored in that city’s harbor, labor agents or other resourceful types tried to entice those bound for Boston to try their luck in New York (usually under false pretenses of gainful employment). Transfers on land came with their own challenges. In July 1867 E.P. Williams, a bureau representative in New York, enlisted the police to escort forty-six passengers from one boat to a different one that would take them on the final leg to Boston. The frightened men, women, and children endured taunts and insults as they made their way along the docks. Stopping in New York was a “beastly business,” according to Williams, made even more “villainous” because any delay meant that the ship’s captain would only grudgingly provide more rations than he had anticipated, although the bureau had to pick up the tab for the extra food.

Armstrong expressed apprehension against “exposing young women to the approaches of any parties in New York or elsewhere along the route.” He feared unscrupulous agents would take advantage of migrants, especially those traveling without close kin: “Every means that ingenuity and the prospect of profit could suggest would be employed.” He was also aware of instances where crew members, as well as labor agents, used girls and women for “base purposes.” Once in Boston, all bureau-sponsored travelers should be met at the dock by a certified agent, but he knew there was “an occasional escape.” In some cases, relatives and former acquaintances swooped in and spirited away migrants promised to specific employers.

The summer of 1867 was the high-water mark for migration to Boston. One day bureau agent James J. Gardner had trouble fetching the day’s arrivals from Central Wharf. He knew from experience that passengers would “leave the boat etc. off at the representation of anyone, frequently, or by false inducement held out, or by making false statements themselves [the migrants] of having paid their fare, or received special direction.” The boat had sailed into Boston Harbor at 4:30 am, much earlier than usual, and though Gardner rushed down to the dock and arrived, breathless, at 4:40, he was able to collect only seven of his fourteen charges. One woman had hurried away after telling Gardner that her husband was in Boston, and she had directions to the place where he was staying. Two others left the boat, and in the “mist of the morning had vanished away.”

Excerpted from No Right to an Honest Living: The Struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era by Jacqueline Jones. Copyright © 2023 by Jacqueline Jones. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.