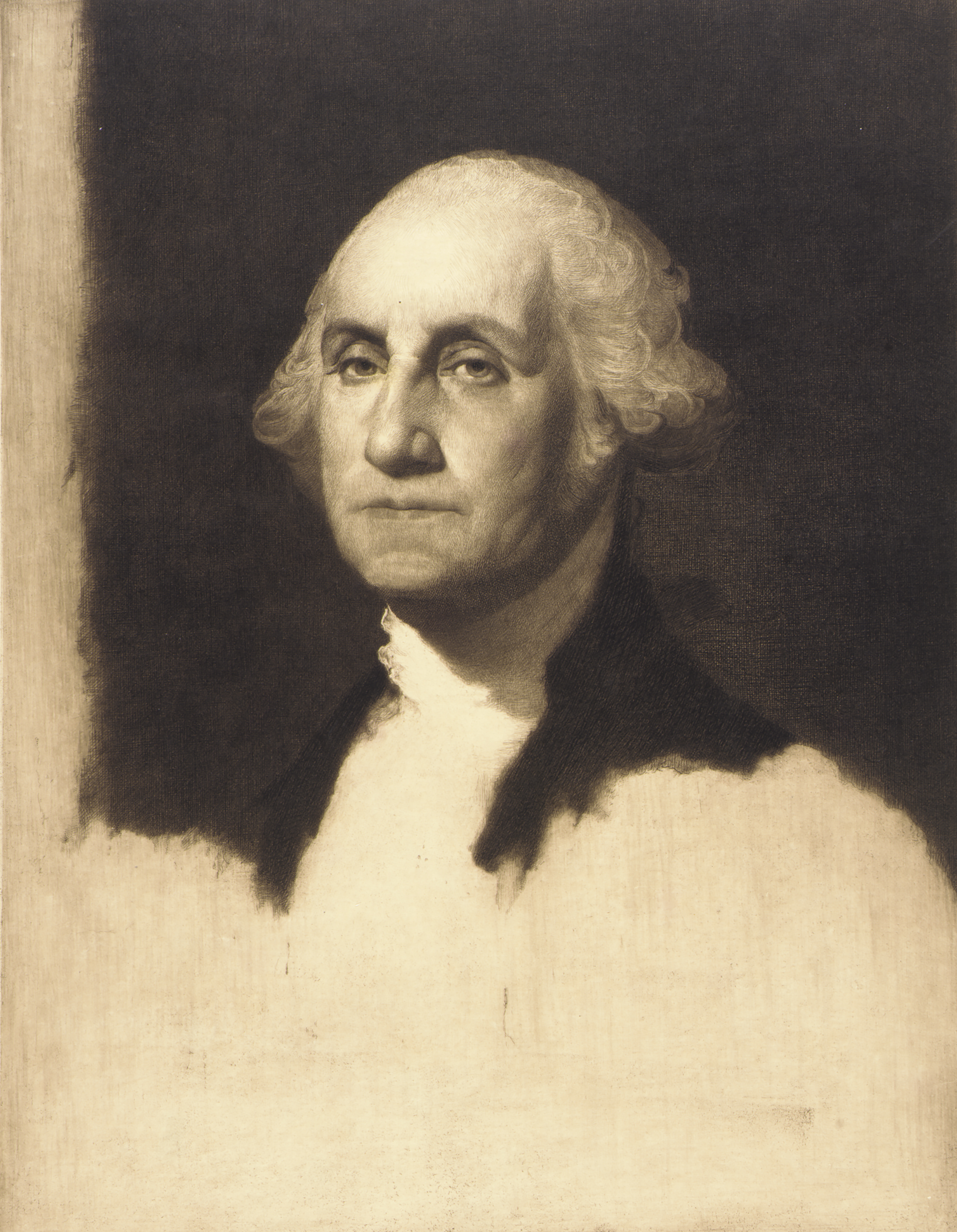

George Washington, by Jacques Reich. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Chicago Society of Etchers.

In the Early Republic, a man’s reputation determined every social, political, and economic opportunity and interaction. It opened doors for trade partnerships, decided who could obtain credit, and served as political currency. Reputations were so important that men engaged in a highly regulated system of written warfare, which sometimes culminated in duels to defend slights to their honor. In order to carve out a successful career in public service, gentlemen had to establish a reputation as virtuous republicans. They were supposed to be talented and exceptional. They were expected to carry these principles into their federal positions—to bring honor and prestige to the office, but not aristocracy. Yet the meaning of these generalities differed from one person to another. What appeared republican to a New Yorker might seem downright aristocratic to a North Carolinian.

Furthermore, no existing governing customs or legal precedents existed to guide Washington and the first generation of officeholders. The lack of guidelines filled each new scenario with additional pressure, but also left officials without a rubric to assess their actions. With no other benchmark, officials turned to public opinion to measure their successes and failures—a highly contested process.

All Early Republic officials shared a constant dread that their fellow citizens might condemn their actions. Washington in particular wanted feedback “not so much of what may be thought the commendable parts, if any, of my conduct, as of those which are conceived to be blemishes.” Finding that careful balance between strength and virtue proved challenging. David Stuart, who had married Washington’s stepdaughter-in-law in 1783, regularly funneled reports to Washington from Virginia. A few months after Washington’s inauguration, Stuart shared criticism that he had heard in Virginia about Vice President John Adams appearing too monarchical. Washington offered a half-hearted defense of Adams. He replied that although Adams sometimes adopted a high tone, he only used a carriage with two horses. Washington expected Stuart to understand that Adams’ use of a relatively modest form of transportation conveyed his republican character. While this distinction might seem silly in the twenty-first century, it demonstrates how Washington, Adams, and others in the Early Republic carefully crafted and dissected each action for hidden republican and aristocratic meaning.

Before the advent of sophisticated polling measures and widespread suffrage, public opinion was hard to gauge. Politicians relied on a few methods to deduce the thoughts of their fellow citizens. First, a network of private correspondents passed along the opinions of their friends, family, colleagues, and acquaintances. These networks expanded far beyond their local communities and allowed politicians to keep tabs on developments across the United States and around the world. Politicians also collected pamphlets, which articulated specific arguments. They were usually signed by the author, which conveyed a great deal of seriousness because the author was willing to stake his name and reputation on the argument contained in the pamphlet. Because they were expensive to produce, pamphlets afforded the wealthy and connected a venue to share their ideas. Pamphlets were printed in relatively small numbers for a limited audience with very specific circulation. Broadsides, large printed sheets similar to posters, and newspaper editorials offered a more informal approach. They were cheaper to create, often anonymous, and recirculated through numerous newspapers. As a result, they were generally considered “beneath the notice of elite politicians.” That is not to say elite politicians did not notice them, but they considered the medium too undignified to merit a response.

The combination of letters, pamphlets, broadsides, and newspapers offered politicians a fairly thorough report on the opinions of white, literate males. Although politicians often exchanged letters with female family members or friends, these types of published and private communications rarely conveyed the emotions of working-class women, illiterate men, Native Americans, or freed or enslaved African Americans. These were not the constituencies politicians worked to represent.

Washington’s efforts to sidestep criticism often worked. On April 23, 1789, Senator Richard Henry Lee brought forth the issue of how Congress should address the president. Although the constitution labels the office “President,” it does not specify how the individual should be addressed. On one side, Vice President John Adams and the majority of the Senate advocated for a more extravagant title that would bestow prestige and respect on the new executive branch. Adams endorsed “His Highness the President of the United States of America, and Protector of their Liberties.” The House of Representatives, and most American citizens, preferred something simpler, such as “President.” Washington studiously avoided giving any indication of his preference. On May 14, 1789, Senator William Maclay of Pennsylvania confessed in his diary that he had no clue how Washington felt about the dispute that became known as the Title Controversy. Maclay served as one of the most vocal opponents of the more regal titles proposed in the Senate and noted his contempt for Vice President Adams for advocating “titles & honors.” He asserted that Washington had not expressed opposition to titles or else he “would have heard of it.” Edmund Randolph shared with James Madison a popular report circulating in Virginia, holding that Washington had written to John Adams threatening to resign if Congress approved an ostentatious title for the president. Many newspaper editorials assured American citizens that Washington bore no blame for the proposed titles. The New York Daily Advertiser claimed, “Our amiable and truly excellent president, we are credibly informed, wishes no badge, which the constitution has not expressly allowed, to distinguish him from his fellow citizens in general.”

Although Washington did not reveal his position while the Title Controversy raged in Congress, he later expressed relief at the outcome. On July 26, 1789, Washington wrote to David Stuart that the question of titles “was moved before I arrived, without my privity or knowledge—and urged after I was apprised of it, contrary to my opinion; for I foresaw and predicted the reception it has met with…Happily, the matter is now done with, I hope never to be revived.”

Armed with the public’s opinion, Washington set out to create a working and social environment that befitted a republic. After receiving responses from his advisers, Washington’s first order of business was to create a social calendar that was sufficiently warm and open, while also establishing respect for the new executive. Twice a year, on February 22 and July 4, Washington opened his home to the public to celebrate his birthday and the birth of the nation. On those days, cannons placed at the end of Market Street boomed to announce the start of the festivities. Units of Society of Cincinnati veterans marched in full regalia to the President’s House, where they mingled with upstanding citizens. Hundreds if not thousands of visitors filled the drawing rooms, dining rooms, hallways, and landings. They drank punch, offered cheers to Washington’s future health, and enjoyed music played by bands in the street.

Although Washington opened his doors on special occasions, he could not welcome random visitors to the house or else a daily continuous stream of guests and office seekers would have made his work impossible. Instead, Washington hosted weekly levees: any man dressed in respectable attire could enter the president’s home every Tuesday afternoon. Washington balanced the open-door policy with strict protocol. He dressed in a velvet suit, wore a ceremonial sword, and greeted each guest with a formal bow. The attendees were then shown to their place in a large circle. Washington slowly walked around the room and exchanged a few words with each guest. After he concluded his circle, the levee ended.

One step below the formal levees, Martha hosted her weekly drawing-room gatherings on Friday evenings, which George attended as a guest. These soirees included both men and women and required an invitation. Martha’s drawing rooms provided an opportunity for George to receive diplomats, congressmen, government officials, and prominent families. In the Early Republic, women could not participate in politics or government. Therefore, when women were present, events were considered private and the conversations were outside the realm of masculine politics. Of course the reality was much more political than anyone acknowledged, and women read, discussed, and wrote about these issues. Because Martha hosted the drawing rooms, George was free to mingle with the guests and engage in conversations about theater, literature, and, of course, politics. Washington used the social nature of these events to his advantage—he dropped hints about his preferences on legislation under consideration by Congress without appearing to interfere with the legislature.

Finally, the Washingtons hosted private dinners once a week. They invited politicians, government officials, and their friends. The department secretaries and their families frequently attended these dinners. As Washington planned his dinners over the course of a congressional session, he carefully selected guests from each branch of government and from all states. He made sure to include all members of the federal government, avoid charges of favoritism, and refrain from giving offense to any one delegation. A dinner invitation to the President’s House helped foster emotional ties between the guests and Washington—and, by extension, with the new federal government. Furthermore, by inviting officials from differing states, he could subtly build coalitions and support for his policies.

In June 1792, Edward Thornton, a British citizen, attended one of these dinners. Thornton served as the secretary to George Hammond, the British minister to the United States. While in the United States, Thornton frequently wrote to his mentor and financial backer, James Bland Burges, an undersecretary for the British Foreign Department. In one of his missives to Burges, Thornton described Washington’s efforts to straddle the line between republican virtue and respect for the office of the president. Washington clearly harbored a “certain dislike of monarchy,” Thornton reported, noting that this dislike seemed a bit hypocritical given that Washington “love[d] to be treated with great respect” and traveled “in a very kingly style.”

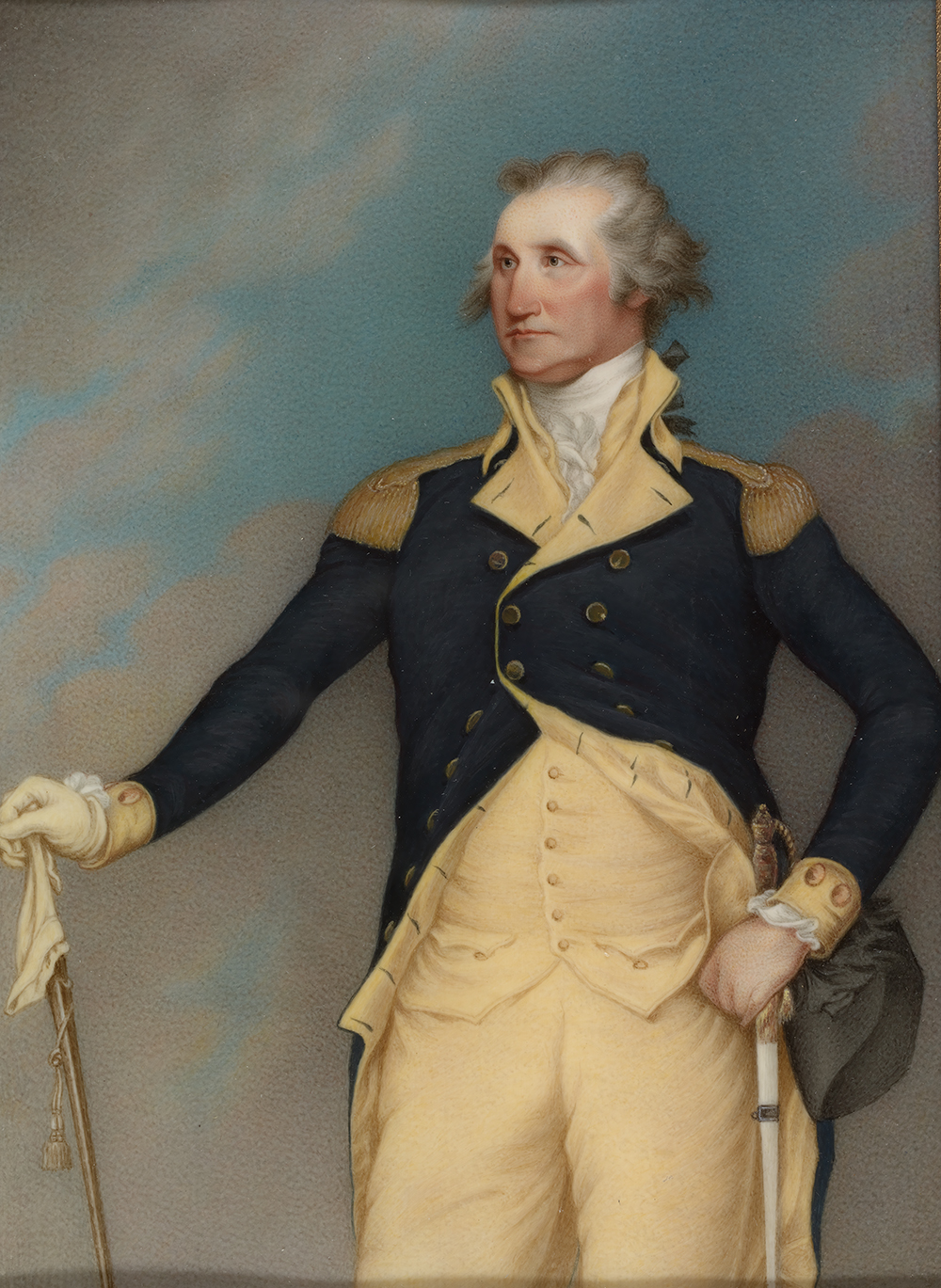

Thornton also highlighted how Washington carefully orchestrated his every public action and appearance. For most travel, Washington rode in an ornate cream-colored coach pulled by six matching horses and attended by liveried coachmen. The coach was one of the fanciest in the United States and recognizable to all who saw it. Washington knew that his fancy coach might remind some citizens of the trappings of monarchy, however, so he balanced it by taking a daily walk on the streets of New York City and then Philadelphia. Walking must have provided little pleasure to Washington. He much preferred to ride a horse for exercise rather than stain his boots with the muck and waste that flowed onto the city streets. But Washington was a conniving politician who carefully crafted his image. He took his walks to convey that he was no better than the average citizen who trudged through the city streets. Washington’s contemporaries understood these walks as a political statement and applauded his assertion of republican virtue.

Excerpt adapted from The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution by Lindsay M. Chervinsky, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.