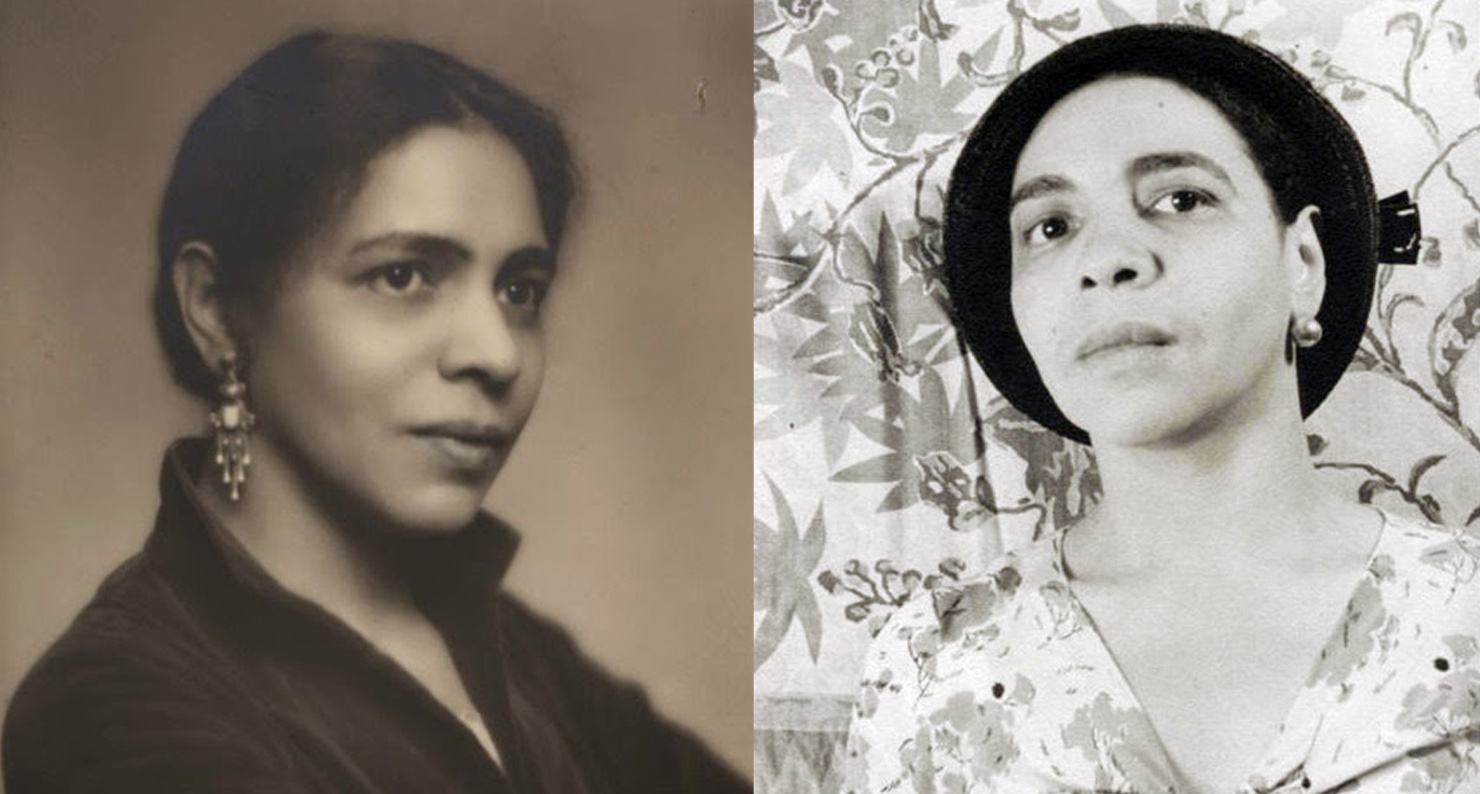

Nella Larsen in 1928 (left) and photographed by Carl Van Vetchen (right).

The tenant in the ground-floor apartment at 315 Second Avenue lived alone. She was long divorced, had no children, and did not see much of anyone. For almost twenty years, starting shortly after the Second World War, she’d worked as a nurse in the hospitals nearby. The last of her employers was the psych unit at the Metropolitan Hospital on East 97th Street. It was the managers there who sent her into exile at seventy-two, an age she’d concealed precisely because she didn’t want to leave.

No doubt they didn’t think of it as a final blow. They probably thought they were sending her off to rest. Within a year of her last shift, though, she was discovered by her building superintendent lifeless on her bed, wearing a sweater, dress, and socks, just like someone who had laid down for a moment and thought herself right out of her life. The official cause of death was a heart attack around Easter Sunday, 1964.

That is how Nella Larsen, celebrated novelist of the Harlem Renaissance, died.

Thinking about her life is like sifting ashes. You believe you see the clear outline of a message, but it inevitably disintegrates before you can be sure of its sense. The mantle of a “rediscovered writer” has never settled firmly around Larsen’s shoulders; she has a way of resisting the platitudes of remembering. There are scholars and biographers obsessed with Larsen, of course, but their work is rent with (polite, academic) infighting about what her legacy means, tangled as it is with ideas about race and identity that Larsen had conflicted feelings about herself. It’s become clear in the fifty years since her death that there was a lot Larsen didn’t want us to know.

Everyone’s life contains a certain measure of unchosen solitude, but whoever handles that ladle was horribly generous to Nella. She was a deeply lonely person. Even her family was not one she clearly belonged to. Larsen was born in 1891 to a white Danish immigrant mother and black father in a rapidly segregating Chicago. Her mother, soon a widow—the death of Larsen’s father is shrouded by a lack of documents—took a white man for a second husband and had another daughter with him. Sixty years later, when the little sister inherited the $35,000 Larsen had left in her savings account, she reportedly said, “Why, I didn’t know I had a half-sister!”

That was a lie—the children had gone to school together, and had been, however lightly, in touch as adults—but it reveals a yawning, despairing sort of gap. Larsen rarely spoke of her family in adulthood. She left no letters or diary that would tell us where her inner compass was on them, either. We have only the occluded lens of her fiction. Larsen’s first novel, Quicksand, is partly autobiographical in subject matter and wholly bitter in tone. It cuts to the quick with all the savageness granted by rich experience. This, for example, is the reason the heroine Helga Crane gives for her mother’s hated remarriage: “Even foolish, despised women must have food and clothing, even unloved little Negro girls must be somehow provided for.”

What categories Larsen could have been said to clearly belong to—she, as we say now, “identified” as a black woman—had boundaries built by others. Larsen was just five when the United States Supreme Court decided that “separate but equal” would be the law of the land in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The public consequences of that ruling have been well documented, but as Larsen’s most recent biographer George Hutchinson pointed out, it was those who blurred the color line as Larsen did who “bore the psychological brunt of the law.” From the beginning the message was clear: you don’t fit, not anywhere.

Larsen would eventually gain a measure of place in Harlem among the members of its Renaissance. Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen were part of her wider circle, along with names better known then than they are today. (“You never read Nella Larsen?” a character asks in Hughes’ 1958 short story “Who’s Passing for Who?” “She writes novels…She’s part white herself.”) But Larsen did not barrel headlong into writing, instead she sidled up to it slowly like a guest unsure of her footing at the party. She never finished high school, trained first as a nurse and then a librarian, married a physicist of great renown, Elmer Imes, who would tie her to Harlem. She was well into her thirties before she met Carl Van Vechten.

Van Vechten was a white man, and in subsequent histories of the Harlem Renaissance this has subjected him to an entirely fair amount of scrutiny. In his travels among the blacks of Harlem, he positioned himself as an expert on the black experience; he wrote a novel whose title I am loath to reproduce here because it bears the n-word.

But his role as a connector was undeniable, ushering black writing to white attention in an era when it otherwise might have languished alone. All of her writing life—a short life actually, only ten years or so—Larsen was a willing pet of Van Vechten, who brought her around to all his publishing friends. In a biographical sketch she gave her first publisher, she described her hobbies as “bridge and collecting Van Vechteniana.” It was Van Vechten who introduced her to Alfred A. Knopf, who would publish her novels.

Quicksand came out to a certain degree of anticipation in 1928. “It was rumored recently that a Harlem lady was about to publish a novel on the theme of miscegenation,” wrote a reviewer in the New York Amsterdam News. “It was expected with eager curiosity; people wondered whether it would be pro or con.” Quicksand was neither, more a novel of aftermath. It won its author an award anyway, the bronze Harmon medal.

She followed it quickly with Passing in 1929, the novel for which, in our era, she is probably best known. More controlled and succinct than Quicksand, it follows Irene Redfield, a black woman whose childhood friend Clare Kendry is “passing” as white. Even Clare’s husband does not know her true identity. Irene cannot help but be frustrated though she is self-aware as to cause:

Later, when she examined her feeling of annoyance, Irene admitted, a shade reluctantly, that it arose from a feeling of being outnumbered, a sense of aloneness, in her adherence to her own class and kind; not merely in the great thing of marriage, but in the whole pattern of her life as well.

By contrast to this sort of thinking from Irene, in the novel Clare is kept a silhouette. Her motivations in passing are not hard to understand but they come off as an affront to Irene. All accounts suggest that passing was never a strategy available to Larsen; all her life she’d clearly appeared black to other people.

Partly because Van Vechten loved the draft, Knopf became greatly excited about Passing, positioning it as an emblematic narrative of life on the “color line.” He put a lot of marketing money into the novel. And like Quicksand, it got excellent reviews. But in the interviews that followed, Larsen began to make missteps. She managed to insult Countee Cullen in an interview for the New York Telegram, the same one where she referred to Van Vechten as a “devil.” Swiftly she sent a letter of apology to Van Vechten, saying the reporter had mischaracterized and misquoted her about this and other matters:

Carl dear,

I am so upset

I’ll never be interviewed again!...

Three Harlem Negros have registered their protests…because I am reported to have stated that it’s perfectly all right to send Negroes around to the back door.

Tonight when we got the damned paper Elmer rose in the air because he thinks I was “trying to pose as a silly uplifter of the race.”

All these things are nothing—

But when I read that I had referred to you as a devil I almost had a stroke of paralysis…

I don’t know at all what to do about it. I could die of rage and mortification. In fact I see no way out except suicide.

Please come to my parties anyway.

Probably she was right about being quoted out of context. Like many people who feel that rejection may inevitably follow from any human contact, Larsen was extremely careful about self-presentation. Sometimes this manifested itself in beautiful outfits, for while she didn’t believe in “loud colors” she liked wearing nice fabrics and was often said to love green. It also meant she relied on manners to close herself off, always polite but distant. An acquaintance interviewed by Thadious Davis, another of Larsen’s biographers, may have put his finger on the problem when he said her “manners were something that people who don’t have, but admire, resent not having.”

Manners, however, could not cover certain fault lines. In 1930, Larsen published a short story, “Sanctuary” in the middlebrow literary magazine Forum. It was the kind of tale you’ve heard a hundred times: an old woman shelters a criminal only to find that the criminal has murdered her own son. It was also the plot arc to a prior story published in The Century by a British writer named Sheila Kaye-Smith. If it were merely a matter of plot similarity, the issue would have been easily resolvable, but the structure of the paragraphs were terribly similar.

A letter came in to the magazine: had the Forum editors noticed the similarities? They had not, and asked Larsen to see drafts. In her reply to the letter, Larsen explained that the story had been told to her by a patient she had nursed in her youth, though she related this with a trace of light panic:

I haven’t as yet seen the Century story, but it seems to me that anyone who intended to lift a story would have avoided doing it as obviously as this appears to be done… Lately, in talking it over with Negroes, I find that the tale is so old and so well known that it is almost folklore. It has many variations: sometimes it is the woman’s brother, husband, son, lover, preacher, beloved master, or even her father, mother, sister, or daughter who is killed. A Negro sociologist tells me that there are literally hundred of these stories. Anyone could have written it up at any time.

Most cursory tellings of Larsen’s life cut off at this incident, blaming it for her withdrawal from writing. But in fact, Larsen won a Guggenheim shortly after with the purpose of writing another novel. We know from the letters of others that she completed a draft or two; we also know that most people who saw those drafts deemed it no good.

Larsen was distracted, largely by the fact that the one bit of family she’d chosen, her husband Elmer, had begun a long and dedicated affair with another woman at Fisk University in Nashville where he was teaching. The end of the marriage was long and protracted. Larsen spent time in Europe trying to recover from the revelation of the affair. A final reconciliation attempt was so dramatic that African American newspapers ran tabloid-style coverage when the break became official in 1933.

The “jump” from the window was Larsen’s, but it may have been rumor—the articles were wrong to think it had been Europe that had started the couple’s troubles. All the same, something snapped. By 1938, Larsen cut off all her friends from her time in publishing. She moved downtown to Second Avenue and apparently lived off her alimony. She published nothing. And she did not rejoin the world until she took a nursing job again, in 1944.

Why vanish? For years afterward her Harlem friends, including Carl Van Vechten, searched for her. Hutchison’s biography traces their letters in painstaking detail—her friends record themselves as truly desperate to find her but also coy on why. It seems she may have become an alcoholic or a drug user and they were reluctant to come out and say it. Van Vechten knew his letters were going to be read. He was actively depositing them in an archive that he had built with others to preserve the record of the Renaissance. He may simply not have wanted to violate Larsen’s privacy.

But it puts the reader in a bind now, trying to collect the pieces of a life that would rather be forgotten. We have only the outward Nella, the manners, the careful presentation of the novels, the curious incident of plagiarism. Any small bit of knowledge added now only makes the gaps more apparent. Recently, a scholar named Erika Renée Williams discovered that “Sanctuary” may not have been the only time Larsen copied something. As it turns out, the opening of Quicksand is a mirror image of a John Galsworthy story, “The First and the Last,” (Larsen always did say that Galsworthy was a writer she admired.)

It was a dark room at that hour of six in the evening, when just the single oil reading-lamp under its green shade let fall a dapple of light over the Turkey carpet; over the covers of books taken out of the bookshelves, and the open pages of the one selected; over the deep blue and gold of the coffee service on the little old stool with its Oriental embroidery. Very dark in the winter, with drawn curtains, many rows of leather-bound volumes, oak-paneled walls and ceiling. So large, too, that the lighted spot before the fire where he sat was just an oasis. (“The First and the Last”)

Helga Crane sat alone in her room, which at the hour, eight in the evening, was in soft gloom. Only a single reading lamp, dimmed by a great black and red shade, made a pool of light on the blue Chinese carpet, on the bright cover of the books which she had taken down from their long shelves, on the white pages of the opened one selected, on the shining brass bowl crowded with many-colored nasturtiums beside her on the low table, and on the oriental silk which covered which covered the stool at her slim feet. It was a comfortable room, furnished with rare and intensely personal taste, flooded with Southern sun in the day, but shadowy just then with the single shaded light. Large, too. (Quicksand)

In the modern world such mirroring would be a serious offense, a subject for thundering criticism, a stain on a great writer’s work. In a writer over fifty years dead, and especially in one as self-preserving, hesitant and distrustful as Larsen, it is something more like a puzzle piece. Or, to put it another way, another brick in the edifice that Larsen seemed to spend her whole life constructing around herself. All writers try to hide, at least a little, in their work. Some use flowery language to throw the reader off the scent of the real person writing; others construct whole other worlds so they won’t be accused of writing only about themselves. Perhaps for Larsen the work of other writers was another simply a way to conceal herself. We’ll never know, because like just about everything else about her, she refused to tell us.