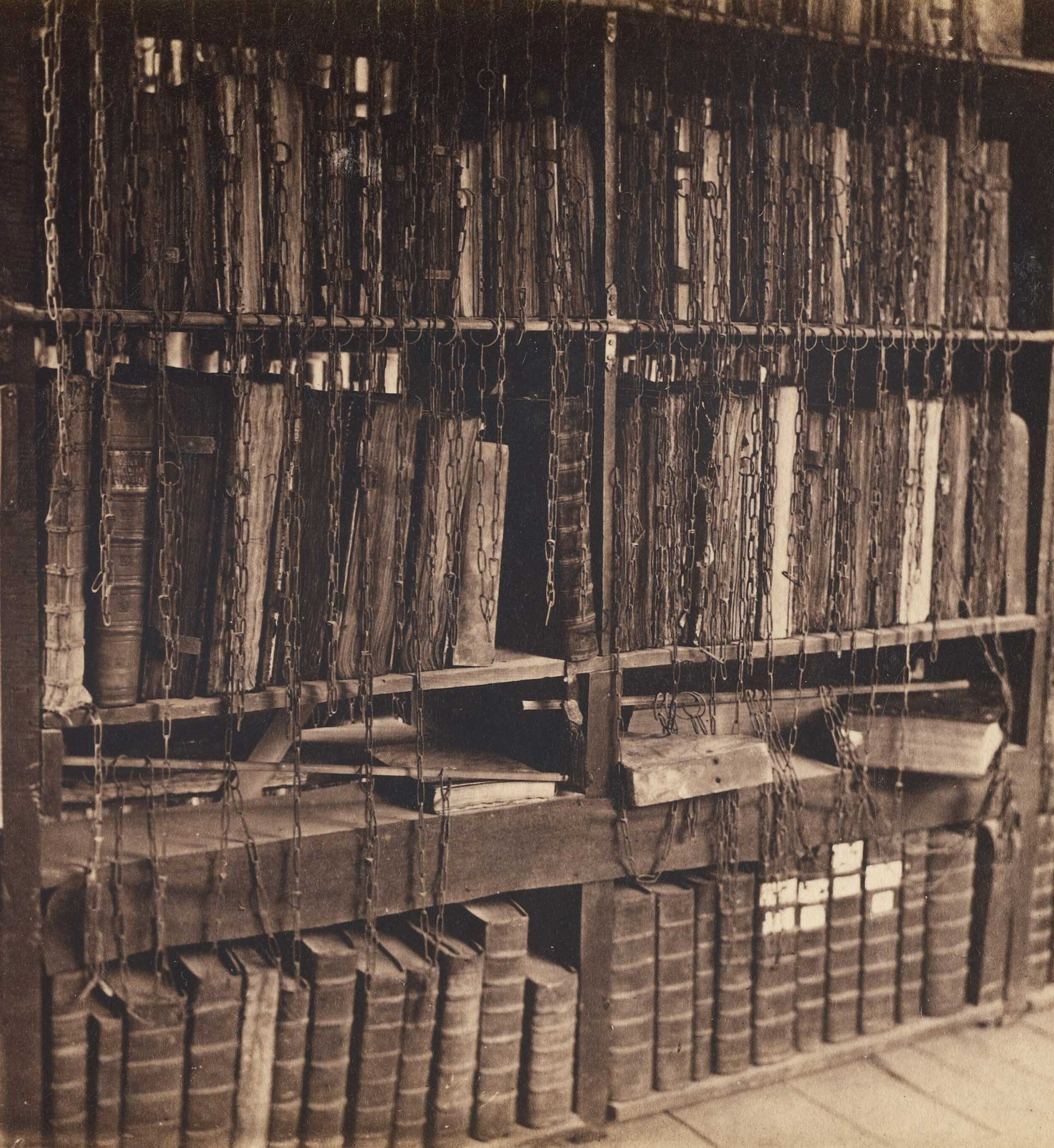

Chained books in the Hereford Cathedral library, c. 1860. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

In late spring 1928 librarians in the rare book collections at the Huntington Library in Southern California noticed that something was feasting on the volumes in their care. Rail and utilities titan Henry E. Huntington had established the library in 1920, spending a small fortune to gobble up a number of the largest and finest rare book collections in a relatively short time, and creating a truly priceless set of artifacts. Though Huntington died in 1927, he intended his collection to live on long after him, but as the librarians discovered, the volumes were literally too full of life. The problem with assembling a massive collection of books is that you necessarily collect the very organisms that feed on books.

Variously known as Anobium paniceum, the bread beetle, or the drugstore beetle, bookworms had been known to eat their way through “druggists’ supplies,” from “insipid gluten wafers to such acrid substances as wormwood,” from cardamom and anise to “the deadly aconite and belladonna,” wrote the librarian Thomas Marion Iiams, who led the preservation effort at the Huntington Library. He noted in an account of his struggles in Library Quarterly that the bookworm displays a “universal disrespect for almost everything, including arsenic and lead.” Iiams was new to the librarian profession and was certain that more experienced overseers of fine collections would have a solution to his bookworm problem. In haste, Iiams wrote letters to much older libraries and repositories—the Huntington itself was only eight years old—to learn precisely how they rid their precious books of the pest. He was alarmed to find that no one, not librarians at the Vatican nor at the oldest libraries in Britain, could offer a definitive prescription for how to protect books against the hardy insect. A number of the librarians he consulted thought bookworms to be a myth, and thus offered no help at all.

The letters, telegrams, and reading recommendations Iiams received mainly offered reasons why you can’t kill bookworms. His colleagues elaborated from afar the bookworm’s astounding resistance to traditional pesticides, its voracious appetite not just for book pages but for leather covers, for even the starchy glue that holds book bindings together. From those that did not doubt the bookworm’s existence or tenacity, Iiams received suggestions that ranged from the highly toxic, such as spraying books with formaldehyde—which is effective for preserving dead humans but a potent carcinogen for living ones—to the comical, such as sprinkling the shelves of the library with “a little fine pepper.” Other correspondents suggested that the latter tactic would have been ineffective since, according to The Principal Household Insects of the United States (1896), bookworms are actually “partial to pepper.” The United States Bureau of Entomology responded to Iiams’ query by admitting it had “never made a thorough study of insects affecting books.” It had, however, fumigated libraries with hydrocyanic acid gas, but mainly to destroy “such external feeding pests as cockroaches and silverfish and such nuisances as bedbugs.”

Iiams grew up in Pasadena, and if he ever went to the Pasadena Public Library as a young man, he would have regularly used fumigated books. Amazingly, librarians considered the use of toxic fumigants to be consistent with a desire for “purified” air, probably because they were less concerned by air filled with toxins than the spread of contagious disease. As one epidemic after another swept through increasingly densely populated urban areas in the early twentieth century, public health officials newly empowered by a broader acceptance of germ theory sent notices to libraries when outbreaks occurred. These edicts forced libraries to close in some cases, to fumigate books in others, or even to burn books loaned to borrowers infected with yellow fever, spinal meningitis, scarlet fever, or bubonic plague. In 1908 Pasadena librarians took the precaution of fumigating 1,200 of the most circulated books. Several years later, they would begin fumigating all of the library’s books as a matter of course.

From the beginnings of the public library system, the public and open nature of book stacks provoked fear and the desire to purify the library’s aisles and reading rooms, to exclude both disease and social undesirables. In 1883, the same year as Andrew Carnegie’s first library construction grant, Charles Ammi Cutter, librarian of the Boston Athenaeum, opened the proceedings of the nascent American Library Association with an address called “The Buffalo Public Library in 1983.” In his futuristic vision, he first enters the delivery room: “There was nothing remarkable about it save the purity of the air. I remarked this to a friend, and he said that it was so in all parts of the building; ventilation was their hobby; nothing made the librarian come nearer scolding than impurity in the air.” According to Cutter, these futuristic librarians vigilantly monitor the temperature and atmosphere in all the rooms: “Everyone must be admitted into the delivery room, but from the reading rooms the great unwashed are shut out altogether or put in rooms by themselves. Luckily public opinion sustains us thoroughly in their exclusion or seclusion.”

The “great unwashed” were those poor and ill-clad individuals who did not conform to emergent standards of bodily hygiene. But cleanliness and purity and hygiene were terms that had deep biological connotations as well; they referred to a clean surface of the body as well as purity of character inside the body at a time when many people believed vice and crime and immoral propensities to be inherited traits. The social hygiene movement attempted to stem the spread of disease, prostitution, and other social problems, with many of its proponents also being eugenicists. Prior to Carnegie’s funding a network of public libraries throughout the United States, most libraries were private and supported by subscriptions. Cutter’s dream of a purified library of the future, a “public” library characterized by exclusion, or seclusion, reveals a central difficulty of creating a truly democratic public space in an era where social Darwinism and eugenics shaped “public opinion.” Up until the late nineteenth century, most libraries shunned lighting by natural gas because it was a fire hazard, not to mention bringing the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning. They “preferred daylight and thus closed their doors by dark” until the arrival of electricity. Light bulbs allowed libraries to stay open later, which brought in more working people, some of whom would have certainly constituted Cutter’s “great unwashed.”

Reading and touching library books brought one into contact with the bodies, germs, and contagions of others. Books, like smallpox blankets, could be infected, and like people with contagious diseases, infected books were fumigated, treated, quarantined, and in some cases destroyed. One researcher experimentally infected books with scarlet fever and found that the dreadful germs could survive for eighteen days even in “lightly infected books.” Public health officials compelled librarians, by law, to literally sterilize books during epidemics by closing libraries and fumigating the stacks with poison gas. The cover of the February 1915 monthly bulletin of the Los Angeles Public Library, Library Books, informed readers of borrowing policies on its front page, concluding with a sentence clearly intended to comfort visitors and allay fears: “The library receives notice of all cases of contagious disease. No book may be drawn or returned by anyone living in a house where there is a contagious disease until the house and the book have been fumigated.” In Portland, Oregon, after a spinal meningitis outbreak in April 1907, the library closed for two days for the fumigation of 7,500 volumes, and any books that had been loaned out were fumigated immediately upon their return by borrowers. At the public library of Toledo, Ohio, books in homes with smallpox, diphtheria, and scarlet fever were not to be returned, and if they were returned, they were destroyed. The Free Library of Saranac Lake, New York, had “traveling libraries” of twenty-five or more books each “loaned to boarding houses for sick people in the vicinity. The books in these collections,” detailed a 1908 article in Library Journal, “are withdrawn permanently from general circulation and are never returned to the shelves of the library. Each time they are sent out they are carefully cleaned and fumigated.” Books and magazines sent through the mail were also suspect. In an 1895 letter to the editor in the British Medical Journal, a public health officer named Charles Porter told of the case of an illustrated newspaper sent from Denver, Colorado, to a family in Stockport, England, which seemed to have infected their four-year-old child with spinal meningitis. Upon reflection, Porter thought that valuable books didn’t have to be destroyed but could be kept for use “in the isolation hospital only,” quarantined along with humans. Less valuable ones could be burned. But neither the fumigation of individual books nor the toxic purification of a library’s air had ever been demonstrated to kill bookworms as effectively as they sterilized books of typhus and other plagues. So even if Iiams were familiar with fumigation techniques in libraries, it wouldn’t have solved his growing bookworm problem. Ultimately for Iiams, preserving his books would require more than just the use of poison gas. He needed a technological solution that would infuse the poison deeply into the books to eradicate even bookworm eggs and larvae.

In the absence of official recommendations, Iiams carried out experiments of his own. He wondered whether he could use a vacuum fumigation tank, previously employed by the California Department of Agriculture to fumigate plants, to force poison gas to penetrate every square inch of infested books. He bought a tank manufactured by the Union Tank and Pipe Company of Los Angeles, which had previously manufactured a “California Floral Bulb Sterilizer” in the 1920s.

While the gas chamber was not an immediately obvious solution to Iiams when he first declared war on bookworms, the fact that he settled on it is not surprising in light of the wide use of both poison gas and gas chambers around that time. In 1924, even as the United States condemned Germany’s use of poison gas as a war weapon, the state of Nevada carried out the first gas-chamber execution, and other states soon followed. California’s gas chamber would claim its first victims in 1938—two men who had killed the warden of Folsom State Prison in a failed escape attempt. Sensational stories about poison gas appeared in newspapers regularly around this time, covering topics ranging from big cities using gas chambers to destroy stray dogs to a desperately sad man sealing his doors and windows with tape, then dropping cyanide tablets in a bucket of acid to kill himself and his paraplegic wife. Still, Iiams needed to find “the ideal fumigant,” one strong enough to kill the beetle, larvae, and eggs. He experimented first with the popular pesticide hydrogen cyanide, also known as hydrocyanic acid gas, and later by its international brand name, Zyklon B. Americans widely applied this poison and others to exterminate perceived threats to the health or safety of the nation. U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) officers fumigated dormitories at a yellow-fever quarantine station in New Orleans, the outgoing mail of prisoners at a leprosy colony in Hawaii, and fruits and vegetables and plants arriving from foreign countries.

As public health concerns persistently blurred into eugenic anxieties and racism, Americans began fumigating people. Government officials fumigated the clothing of Mexican migrant workers in El Paso, Texas, at the headquarters of the Border Patrol, newly formed in 1924, the same year the Immigration Act restricted immigration from southern and eastern Europe, and Asia. From August 1929 to February 1930, USPHS officers at Angel Island—the San Francisco Quarantine Station—carried out experiments, putting cockroaches in a five-hundred-cubic-foot room and gassing them. Angel Island processed many Asian immigrants from 1910 to 1940, holding them and interrogating them in the same facility as this gas chamber for cockroaches. When Nazi scientist Gerhard Peters argued for the use of gas chambers, or disinfektionskammern, in an influential article published in a German pest science journal, he illustrated his text with photographs from the delousing station at El Paso. He would go on to become the managing director of DEGESCH, the company that supplied Zyklon B to death camps across Europe for genocidal atrocities that the Nazis referred to variously as “delousing the nation” or “disinfection” or “self-preservation.” Though hydrogen cyanide was regularly applied to the clothes and skins of people, Iiams thought it was too dangerous to use on his precious books: it left a toxic residue on the pages that might poison librarians and readers in the future. After trying a couple of other poison gases, and with the help of scientists at the California Institute of Technology, Iiams settled on a mixture of ethylene oxide and carbon dioxide that came to be known on the fumigant market as “carboxide.” He went on to treat not only the infested volumes but all of the rare books in the Huntington’s collection, all “foreign” books that entered its collections, and some of the pope’s bookworm-ravaged stacks in the Vatican. Iiams’ innovative method soon attracted national attention.

On January 1, 1933, a photo of the librarian landed on the pages of the New York Times. There is no article accompanying the photo, only a short caption that credits Iiams with devising a “Gas Chamber in Which All Volumes Are Submitted Periodically to a De-Worming Process.” The headline lethal gas chamber for bookworms runs above the image of Iiams standing before a fumigation tank, a book held open in one hand as he examines it through a magnifying glass held in the other, a nearby truck of priceless books already loaded in the tank, their spines sparkling faintly as they await sterilization.

Excerpted from We the Dead: Preserving Data at the End of the World by Brian Michael Murphy, published by the University of North Carolina Press. Copyright © 2022 Brian Michael Murphy Reprinted by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.