Carved bone hairpin with a head in the form of a female bust with an elaborate hairstyle, Roman, first century. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

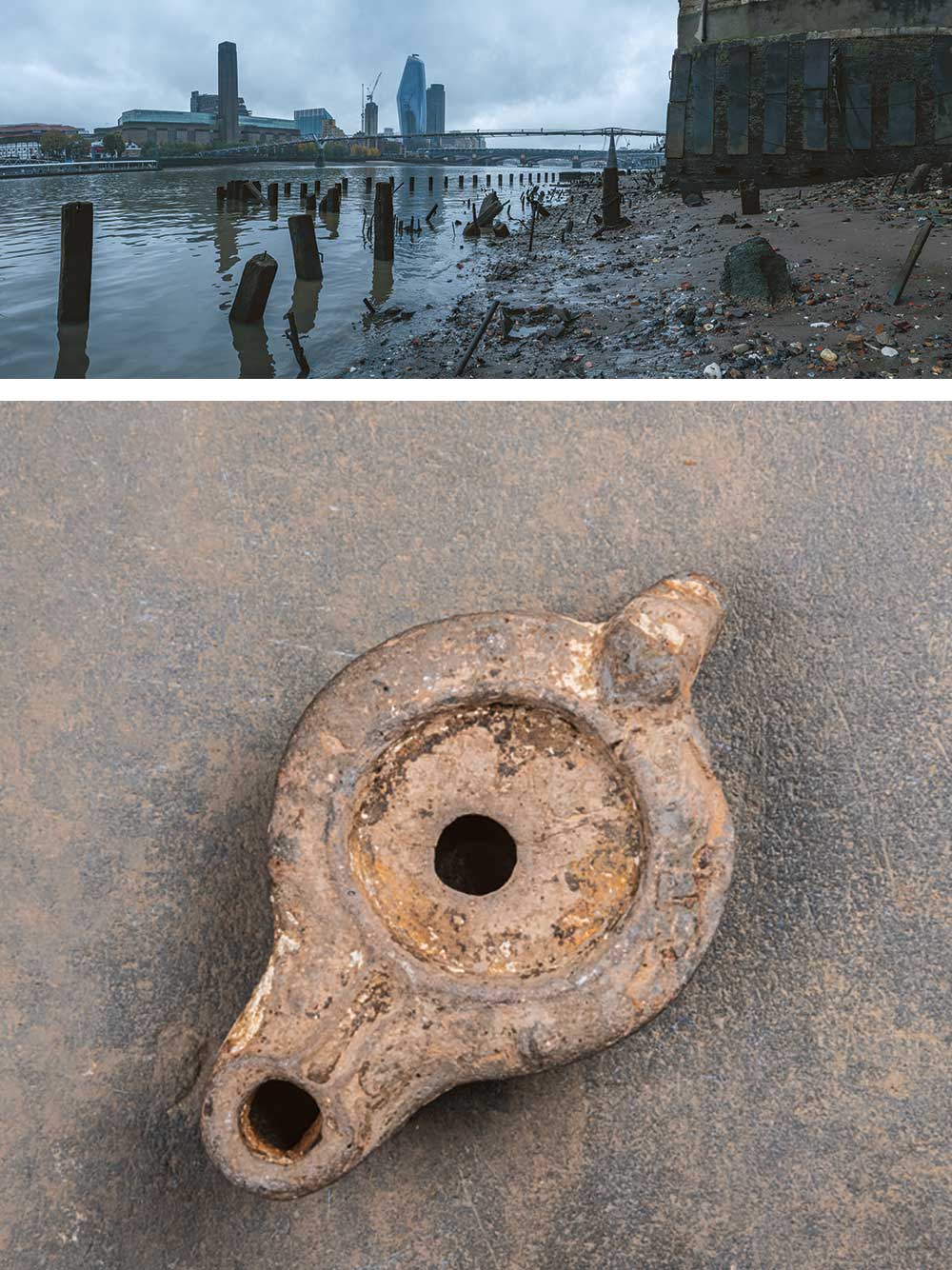

There is a small patch of shingle on the Thames foreshore where bone pins wash up, sometimes hard to distinguish from the shredded plastic straws and decaying plant stems that litter the same area. They were last used nearly two millennia ago to help create the elaborate hairstyles worn by the female citizens of Londinium, the Roman precursor to today’s London. Women could not create some of these styles themselves, and so the last hands to touch these finds may have belonged to an ornatrice: a female hairdresser, who was often enslaved.

Hair was central to Roman ideas of femininity, social status, and even what it meant to be Roman itself. Much of the population of Londinium consisted of Britons who had become Romanized to varying degrees. For the socially ambitious, hairstyles, along with clothing, bathing, and eating habits, could be used to signify their embrace of the Roman way of life. When Britain was first colonized, the fashion was for especially tall and elaborate hair. Wearing one of these complex styles signified that a woman was wealthy enough to afford the time to style her hair. Natural hair was associated with barbarism—the uncivilized other of the Roman world. Hair was also directly intertwined with the exercise of power, through the fashion for hairpieces known as crines empti. Sometimes these were made from captivos crimes—“captured hair”—obtained as a spoil of war. According to the poet Ovid, blond hair from Germany was especially popular. In his book of poetry Amores, a male lover berates his mistress for ruining her hair through using curling irons, declaring: “Now Germany will send you tresses from captured women; you will be saved by the bounty of the race we lead in triumph.” The visit of Empress Julia Domna to Britain from 208 to 211, meanwhile, reportedly led many British women to adopt the Syrian style of hairdressing—crimped in waves on either side of the head with a large coil at the back.

Ornatrices, as hairdressers, were familia urbana—a type of enslaved person who worked inside the enslaver’s home performing chores that freed their enslaver to live, in Roman eyes, nobly. Other roles for enslaved females of this type included cleaners, bedchamber servants, cooks, nannies, maids, wet nurses, and laundresses, while males worked as attendants, gatekeepers, gardeners, animal keepers, and in workshops. Regardless of the positions they ended up occupying, there were common routes leading to their enslavement. After a successful battle, captives were considered part of the plunder and were rounded up and sold to slave dealers who followed the armies. Others were seized by pirates, born into slavery or sold into it as children. Once captured, an enslaved person was prepared for sale using various plant and animal products to “improve” their body and command a higher price at market. Muscle was faked by fattening boys up, while wounds, scars, and other defects were covered with clothing. The enslaved people were then presented to prospective buyers, some of whom were enslaved themselves. A wax and silver fir writing tablet found near the River Walbrook, a Thames tributary, records the sale of a Gaulish female named Fortunata (ironically, meaning “Lucky”) who was bought by an imperial enslaved person, Vegetus, who was himself owned by Montanus, who was in turn slave of the emperor. As the property of their enslaver, an ornatrice, or any other kind of enslaved person, could be sexually exploited or receive harsh treatment for any perceived transgression.

Clumsiness, muttering, noisiness, defiant looks, or simply their enslaver’s bad mood could result in punishment by whipping. Ovid warned any noble woman having a bad hair day against attacking her ornatrice with hairpins. He instead suggested she post a guard at her door to prevent anyone entering and seeing the sorry state of her hair:

And leave your maid alone!

To scratch her face or stick

Her arm with pins—that makes me simply sick

She’ll curse your head each time you touch her; then she cries,

Bleeding on tresses you’ve made her despise.

Bad hair? Well post a door guard; that should work just fine.

Notwithstanding such treatment, the enslaved person often played an active role in creating a life for themselves, albeit within a limited range of options. Some married, although this was not legally recognized, and any children were the property of their mother’s enslaver. Acts of resistance included “wandering” (taking longer than necessary to accomplish a task in order to visit friends), stealing food and money, and spreading malicious gossip about their enslaver with the goal of harming his reputation.

Some of the enslaved eventually succeeded in gaining their freedom, either by saving for a lengthy period to buy it or as a reward for long service or for bearing children. Some who were freed rose high up in the Roman hierarchy. After Boudicca, queen of the Iceni tribe, led an uprising that devastated Londinium in 60, the Emperor Nero sent the formerly enslaved Polyclitus to Britain to head an inquiry. Polyclitus ordered the removal of the governor of Britannia, much to the amazement of the local tribespeople, who “marveled that a general and an army who had completed such a mighty war should obey a slave.” Unlike the transatlantic slavery of the eighteenth century, there was no Roman literature of enslaved people and no abolition movement. The only written sources we have were created by Roman elites who wrote of enslaved people as possessions or vehicles for literary comedy. We can attempt to get closer to their day-to-day existence, however, through the objects they handled. Beakers and flagons were fetched and poured by enslaved waiters. Bowls, jars, and pots were essential items in the kitchens of enslaved cooks. Oil lamps needed to be refilled regularly. Pins were used to create the hairstyles of the elites by ornatrices. Almost any visit to the Thames foreshore can turn up an object that is a testament to the pervasiveness of slavery in Roman society.

Excerpted from Mudlark’d: Hidden Histories from the River Thames by Malcolm Russell. Copyright © 2022 by Malcolm Russell. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.