Sergei Shchukin’s music room in early 1914. Photograph by Pavel Orlov, colorized by Christine Delocque-Fourcaud. Courtesy of Collection Chtchoukine.

The owner pressed the switch, the room was flooded with light, and the paintings emerged from shadow.

“Here’s a Monet…see how alive it is,” said Sergei Shchukin.

From a distance, under the lights, it was impossible to see the paint strokes and touches. One had the impression of being somewhere in Normandy in the morning, looking out of a window. The dew had not yet dissipated and the day ahead promised to be hot.

“Look at Pokhitonov: he’s completely overshadowed by Monet, we have to move him away from there. Here’s Degas with his jockeys and dancers, and here’s Simon…Let’s go through to the dining room, that’s where I have Puvis de Chavannes. And here is one of the Bande Noire, as they say of Cottet. An evening by the sea, just before a storm, with people walking along the quayside. This one is by Brangwyn. And here’s Whistler…”

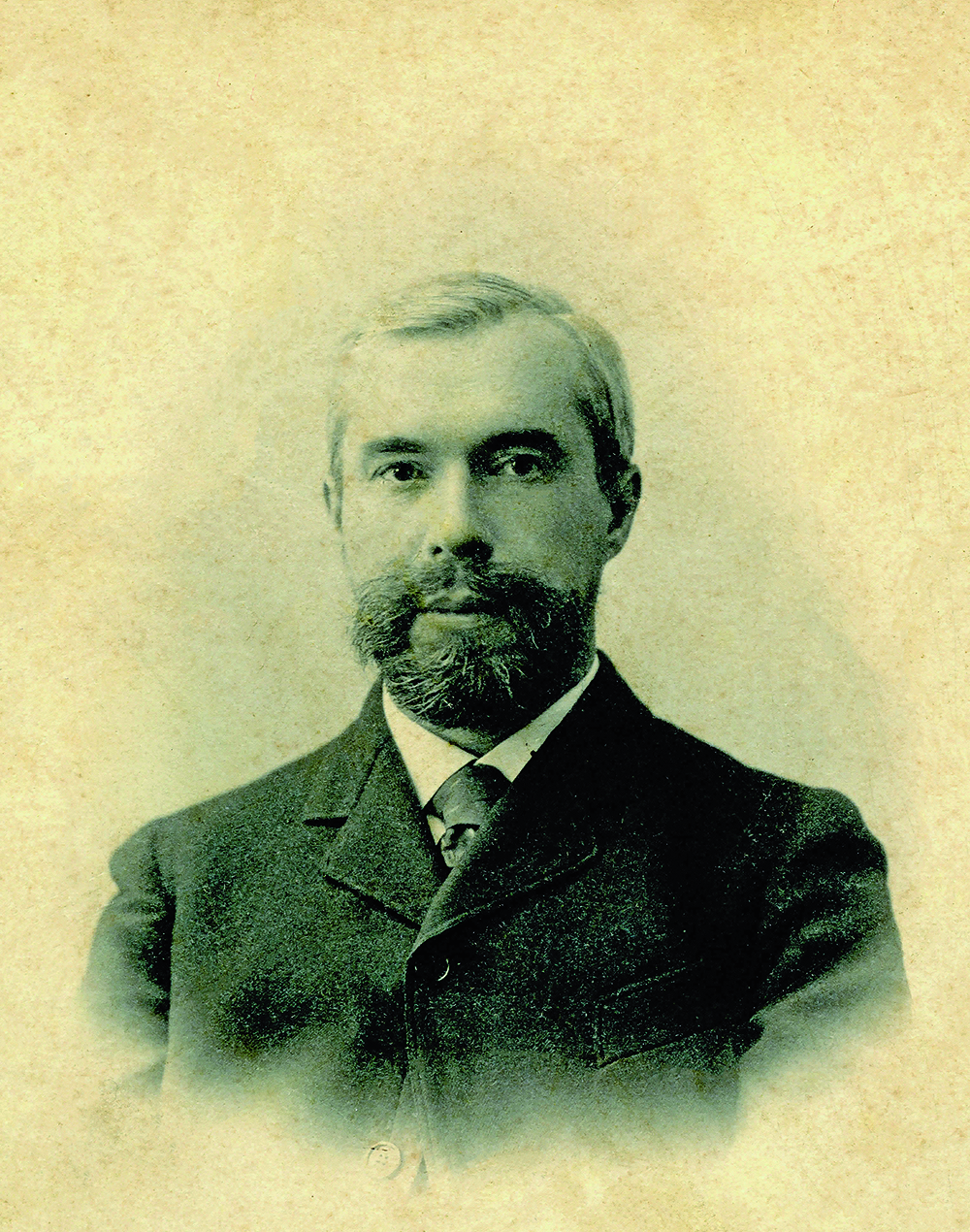

This wealthy textile merchant in Moscow, Sergei Shchukin, has assembled a collection of the youngest painters belonging to the most innovative movements underway in Europe. He has plenty of taste and a special artistic sensibility; the dernier cri of contemporary painting is to be found at his house.

Thus the painter Vasily Perepletchikov described an evening spent at the house on Znamensky Lane in 1900.

There are quantities of Russian and foreign newspapers in the library. Over tea, we spoke of Diaghilev and his review World of Art, of Turner and of Vladimir Solovev. Sergei Ivanovich is abreast of everything, he spends a lot of time in Europe. The children came to say goodnight: nice boys with black eyes, accompanied by their French tutor. They paint, too. In their bedroom there is an easel; across the table are spread a number of studies in which you can already identify the modern style.

It’s time to go home. The master of the house accompanies his guests to the bottom of the main staircase as far as the hallway. On the steps of the old palace, which has seen so many people coming and going over the last century, he is still talking, even though we have already put on our fur coats: “Durand-Ruel is sending me a Maxence any time now, come and see it when it arrives…”

Any young painter visiting Shchukin could expect a similar culture shock.

It always began with the impressionists:

There, right against the glass, grew a tuft of moss delicately adorned with terms of orange, lilac, yellow; one had the impression—and in fact it was true—that the filaments of color actually had roots and were growing out of the canvas in a scented cloud.

So wrote the future avant-garde painter David Burlyuk, who was rendered ecstatic by the texture of Monet’s pictures, with their “tender interlaced plants, divine and strange.”

Adds Perepletchikov:

The wealthy merchant Sergei Ivanovich Shchukin has recently joined the élite of collectors. No one can doubt that he will soon emerge as one of the greatest of his time.

Sergei had already won a reputation in Moscow—and he had only been collecting for two years.

Legend has it that in May 1898, three Russians entered 16, rue Laffitte in Paris, the gallery of the impressionist dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. They were the brothers Sergei and Petr Shchukin and their cousin, the painter Fedor Vladimirovich Botkin.

Inside the gallery, the Shchukin brothers lingered before a series of views of the Avenue de l’Opéra that Camille Pissarro had just delivered to Durand-Ruel. Petr picked out Place du Théâtre-Français, a summer cityscape in which the green foliage of horse-chestnut trees was beautifully rendered. He bought it for four thousand francs. A year later, on April 28, 1899, Sergei Shchukin paid one thousand francs more for L’Avenue de l’Opéra, effet de Neige le Matin. These wealthy Russians, staying at the Grand Hôtel on the Place de l’Opéra, seemed to be buying landscapes like upmarket postcards. The only difference was that they had been painted by Pissarro in his room at the Hôtel du Louvre, way down at the far end of the avenue.

In November, Sergei returned to the rue Laffitte, and this time he bought his first Monet, Rochers à Belle-Ile, typical of the imperceptible shifts of nature so dear to the master. This first Monet cost him ten thousand francs. The following year, Shchukin paid nine thousand francs for Champs à Giverny, and his Parisian brother Ivan bought the superb early study Lilas au Soleil for eight thousand francs on Sergei’s behalf. In late 1900, Sergei went in person to visit Claude Monet and bought one of his iconic Nympheas Blancs: a glorious summer day, a garden of luxuriant vegetation, and a pool covered with water lilies spanned by a Japanese bridge. The following year, he went back to buy La Cathédrale de Rouen, le Soir, which the artist had set aside for him. (The same year, he was to buy another cathedral, Le Midi, from Durand-Ruel.)

In November 1904, Sergei’s tenth and eleventh Monet acquisitions were delivered to the Trubetskoy Palace. One was a canvas freshly painted that year in the master’s latest manner: Le Parlement de Londres, les Mouettes, in which Monet reinterpreted Turner using the mistiest, most extreme canons of impressionism. The other was already a cult classic, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, a reduced version of Monet’s grand canvas. The unknown price of this acquisition—from the German dealer Paul Cassirer—was constantly exaggerated by Moscow’s rumormongers. Whether deliberately or not, the collector also responded practically to a 1900 article by Alexandre Benois in World of Art, in which the critic described this painting as one of the most beautiful pieces of art of the past century. “We dare not dream that a painting like this Monet will ever be brought to St. Petersburg or Moscow,” complained Benois. “Nevertheless, the day will come when history, which always lags behind life, will view such works as great masterpieces.”

Within four years, Sergei had resoundingly proved the critic wrong about the timidity of Russian collectors. By 1904 the first cycle of the Shchukin collection—that of the impressionists and their greatest star Claude Monet—had come to an end. Nevertheless, it had given birth to the legend of the godlike collector Shchukin and his eleven Monets, plus the two Monets belonging to Petr and the collection of paintings by Renoir, Degas, and Maurice Denis owned by the three Shchukin brothers. Already the truth was being distorted. Certain outstanding pictures by painters who were still not understood by the vast majority of people—even though they were worshipped by real connoisseurs—were bought by the Shchukins, along with about fifty other works by other, lesser artists, only some of whom became famous later. Never again after the period 1898–1904 would Sergei himself buy works by so many different painters. At the time, he was learning to understand art as someone tries out a mattress, with the loyal and excellent Petr working beside him throughout the first years. This first “experimental” Shchukin collection still awaits an art historian capable of placing the works and their authors in perspective. Even so, we can discern in the early choices made by Sergei a feature that was later to become his hallmark: that of selecting artists without operating within any kind of system. Whether they were famous or unknown, he went straight for their best work.

The Moscow public had its first chance to discover the impressionists in 1891. Monet’s Meule de Foin, which was destined to play such a decisive part in the future of abstract art, was among the paintings on display. The young Vasily Kandinsky was changed forever when he saw this picture, which was completely revolutionary in its absence of subject matter. Indeed, it turned the Russian aesthetic debate on its head:

The catalogue told me that this was a picture of a haystack. I didn’t recognize it as such to begin with, and my failure to understand it disturbed and irritated me. I thought that nobody had any business painting something so vague. I sensed in some dull way that the work lacked a clear subject, but I also noticed that it exuded astonishing power, a power previously unknown to me, as well as a range of color that exceeded my wildest dreams. I suddenly realized that subject matter was not an indispensable element of this picture.

Another shock wave hit St. Petersburg with the arrival, on January 1, 1899, of the First International Exhibition of Paintings, organized by World of Art in the rooms of the Central Technical Drawing School founded by Baron Alexander von Stieglitz. The main organizer, Serge Diaghilev, played the role of intermediary between a conservative public, which had been taught to revere the ideals of the Wanderers, and younger Russian artists, such as Léon Bakst, Alexandre Benois, Konstantin Somov, the already successful Valentin Serov, the Parisian Fedor Botkin, and others. Diaghilev confronted his “new Russian painters” with their foreign counterparts, who had shown work at the most important exhibitions in Paris, Munich, and London. These included the Germans Franz von Lenbach and Max Liebermann, the American James McNeill Whistler, the Finns Albert Edelfelt and Akseli Gallen-Kallela, and the Norwegian Frits Thaulow. Nevertheless, the bulk of the work came from the French school.

The pitfalls that awaited his attempt to conquer that public were made plain by the newspapers. Vasily Stasov led the charge in the Stock Exchange News, with an article over three columns entitled “La Cour des Miracles” (“The Slums”). Denouncing the exhibition as an “excretion of manners and viscous muck,” he wondered: “What gracious and pure Esmeralda will come to our aid, who will save us from this basket of crabs, monsters, and degenerates, and who will deliver us from their disgusting claws?”

Alexandre Benois immediately responded in World of Art:

A perplexity bordering on horror seems to seize all those who see a painting of this school [impressionism] for the first time. Can it be that amid this senseless disorder of lines and colors, sincere and objective people can actually discover light, sunshine, life, the delicate wonder of color, even poetry?…It is only by educating and developing our taste, and by entering more deeply into works that have so astonished us, that we will discover beneath what we at first take for ugliness, a divine spark that can set our hearts aflame…

It went unremarked that the two pastels by Jean-Louis Forain, Les Courses and Le Foyer du Théâtre, came from a collection that nobody had yet heard of, though it bore the name of a merchant known to everyone in Moscow. The note “Sergei Shchukin Collection” had made its first tentative appearance. Six weeks earlier, Sergei had acquired his first Monet.

Excerpted from The Collector: The Story of Sergei Shchukin and His Lost Masterpieces by Natalya Semenova with André Delocque, translated by Anthony Roberts, published by Yale University Press in October 2018. Reproduced by permission.